China has framed Hong Kong’s pro-democracy protests as a foreign-backed movement that uses “thugs” to threaten the mainland’s sovereignty.

The narrative might be working within the great firewall. Outside China? Not so much.

Beijing’s approach has been quite clumsy, experts say, drawing a sharp contrast to Russia’s success in spreading disinformation on Western social media. Rather than blending seamlessly into the online sphere—where Moscow has demonstrated its skill at camouflage—it’s ridiculously easy to identify China’s efforts as bizarre or even downright false.

“China is much more primitive in terms of techniques,” said Haifeng Huang, associate professor of politics at the University of California’s Merced campus, whose research focuses on opinion shaping in authoritarian settings. “…The goal is different: China is more about self-defense, Russia is more about actively going out, targeting foreign events. China’s goal is to influence Western discourses about Chinese events.”

China’s “blunt-force” recipe

Since the 2016 US presidential election, social media users have grown used to hearing of inauthentic accounts—which are most often attributed to Russia. When Twitter last month said it was suspending more than 900 accounts linked to China, it marked the first time the platform had publicly identified and removed a Chinese disinformation campaign. Facebook took similar action against a handful of pages the same day. The accounts and tweets made public by Twitter offer researchers a chance to study China’s tactics.

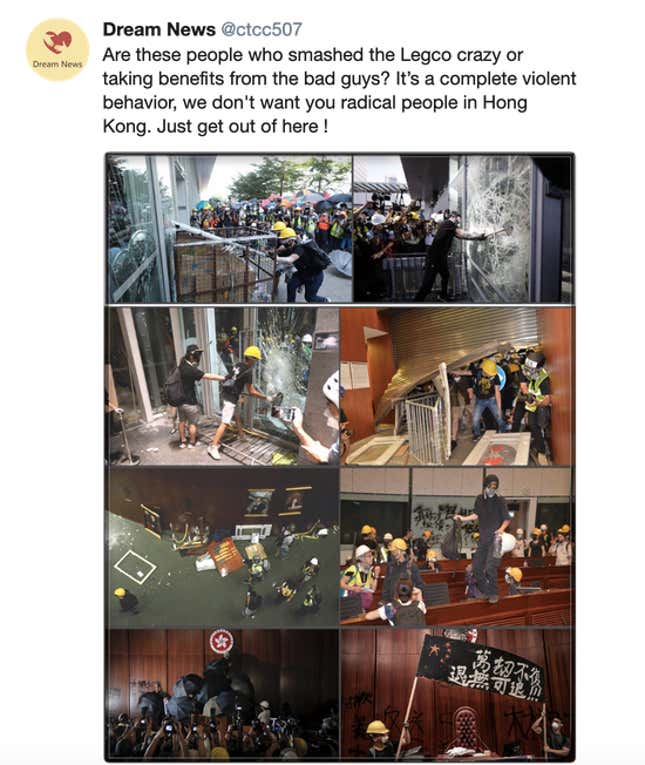

After an estimated 2 million people marched in Hong Kong to protest against the now-withdrawn bill that would have allowed extradition of criminal suspects to the mainland, a Twitter account with a red Chinese flag as its profile picture tweeted in Chinese that protesters dressed in black and linked to foreign agents had attacked police headquarters, “instigating others to march and protest as a means to disrupt Hong Kong.” In other instances, if users scrolled down, they would have seen that two of the accounts with the most retweets in recent days about Hong Kong topics were earlier tweeting links offering nude photos. Others were previously tweeting in Portuguese or Indonesian.

“You sort of scratch the surface and you see something is not right,” said Elise Thomas, a researcher at Canberra-based think tank Australia Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) who is one of the authors of a report this month analyzing Twitter activity aimed at discrediting the protests. The campaign—which was built from repurposing old Twitter marketing or porn accounts to begin tweeting about Hong Kong in April—appeared “hastily constructed,” ASPI’s report said. And perhaps it was, spurred by Hong Kong activists’ own increased presence on the platform.

Yet China’s Communist Party has been very successful at shaping public opinion at home, thanks to a blend of online censorship, patriotic trolls, and directives to state-run media that have intensified under president Xi Jinping, who came to power as general secretary of the party in 2012. Angela Wu, an assistant professor of media studies at New York University, says her research showed that in the five years up to 2016, stances critical of the Beijing government and shaped by liberal democratic ideas were largely displaced by patriotic views.

When China tries to adopt the same blueprint outside the country, with ads and messaging from state-run media working alongside troll accounts on overseas platforms, these efforts run into competing narratives. (Thomas cautions there may be more sophisticated efforts we’re not aware of.)

“Its earlier propaganda measures designed and worked for guiding domestic popular opinion, [which] paved the way for what you see in the present day,” Wu told Quartz via email. “That’s why they look bad and even bizarre.”

One widely panned message was a tweet from state-run China Daily, which rewrote Martin Niemöller’s famous Nazi-era Germany poem about complicity to be about the protest movement, in effect comparing demonstrators to the Nazis. Last week, China Daily’s Hong Kong Facebook account posted the claim that Hong Kong protesters were going to wage terror attacks on Sept. 11, citing an unverified post from messaging app Telegram, used by many protesters to organize—which prompted multiple comments criticizing the page and the Party.

With state-run media actively in the mix, it’s easier to identify the framing China’s trying to push, even when it starts to come from sources not obviously linked to the government, such as from handles with profile descriptions identifying social accounts as a “beer evangelist” or as Ariana Grande fans, as in the data sets released by Twitter. China’s efforts could in fact backfire, for example by adding fuel to the discussion about whether Western papers should continue to carry China Daily inserts, an important part of the country’s overseas self-defense efforts.

“The focus is on telling a good story about China,” said Huang. “Because the Chinese government understands that Western opinion about China is pretty bad.”

Playing offense vs. defense

While China fails at painting a rosy picture of its internal affairs, Russia has had more success blending into discussions of events, in places from Ukraine to the US, to sow confusion.

In the US, Russia’s strategy was to use handles cultivated over years to wade into controversial topics—the Black Lives Matter protests over police violence against African-Americans, gun control, and the hearings on Donald Trump’s Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh.

“They know what the issues are in the American public, they immersed themselves in American discourse,” said Huang.

The Russians established “digital assets months and months in advance, put a huge amount of time and assets building up what looked like credible online personas,” said Thomas, of ASPI. “They really put time and effort in a sort of very careful campaign, targeting different audiences and different kind of messages.”

Kremlin-linked troll farm Internet Research Agency (IRA), was able to reach up to 126 million Americans on Facebook through fake accounts, groups, and ads, according to US special prosecutor Robert Mueller’s Russia report examining meddling in the 2016 election. The IRA bought Facebook ads that led to real-life rallies in Pennsylvania and Florida to undermine Trump’s Democratic rival Hillary Clinton and support him. Fake personas also communicated with Trump’s Republican campaign, which was unaware it was talking to foreign nationals.

Russia’s efforts are likely more sophisticated because of being rooted in the Soviet Union’s long experience with spycraft during and after the Cold War. The hit US television show The Americans was, after all, based on a real group of Russian spies from an operation known as “The Illegals.” China did not have many Western diplomatic ties until the 1970s, and, even then, it was deeply focused on the internal project of economic development.

In addition, Chinese propaganda authorities “do not have a sophisticated understanding of mainstream discourses, perspectives, and public opinion outside China, and don’t know how to engage with Western societies effectively,” notes Huang.

Because Russia’s efforts are more believable, when they do get discovered—and “getting caught is half the point,” Peter Pomerantsev, a senior fellow at London’s Legatum Institute think tank, notes in his new book This is Not Propaganda—they spread disillusionment with the press and popular movement. Finding out something that seemed genuine isn’t breeds cynicism, furthering Russian aims.

Of course, it’s not that Russia hasn’t tried to do what China is attempting—reshape the West’s opinion of itself—but it hasn’t been very successful at it either. In the last decade its efforts saw a shift (pdf, p. 8) “of Russian international media outlets like RT and Sputnik from presenting a positive picture of Russia to the world to giving a different perspective on negative developments in Europe and the US.”

Will China’s propaganda campaigns evolve?

China likely will continue using foreign social networks for issues beyond Hong Kong. With its growing expertise with artificial intelligence, visible in recent popular apps, “deep fakes” could become part of China’s disinformation arsenal. “China’s investments in AI may lift its capacity to target and manipulate international social media audiences,” ASPI noted in its report.

The rise of globally popular apps such as TikTok, one of China’s first to be a big hit overseas, could also play a role. Hong Kong protests have an unusually light presence on TikTok, spurring suspicion of censorship and manipulation.

Beijing’s focus appears to still be mainly on propagating wonky messages about Chinese policy that have little chance of connecting with non-Chinese audiences. Since June, three state-affiliated organizations alone have been contracting for projects costing more than $1 million to grow overseas social media presence.

The country’s Internet regulator, the Cyberspace Administrator of China (CAC), wants to “tell China’s stories with multiple angles, express China’s voice, and get overseas audience recognition and support for Xi Jinping Thought,” according to the contract the CAC offered. That agenda might win points with party elites—the mindset that is part of China’s weakness on messaging.

“People engaged in the operations are more incentivized to please their higher-ups with visible metrics such as numbers of tweets and followers (who cares if the followers are real people) than actual effectiveness of the operations,” Huang, the politics professor, wrote in an email.