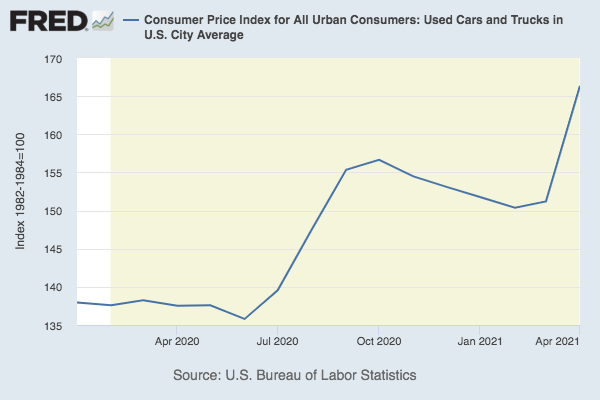

You thought the price of wood was nuts? Just check out what’s going on at car dealerships. After cooling off a bit from a surge last year, the cost of used vehicles suddenly shot up 10 percent in April alone, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ official inflation report on Wednesday. The sudden acceleration was the largest one-month increase in the category since the government began tracking the Consumer Price Index in 1953.

Americans have seen prices on a number of items soar thanks to tangled supply chains that have made it difficult for companies to keep up with demand from flush consumers, who are shaking off the pandemic and ready to spend. (Again, see the price of a 2-by-4.) Used car prices, in particular, have been driven up by a confluence of factors.

First, global automakers have been struggling with production thanks to a worldwide shortage of semiconductors, which has forced them to idle plants and has made it difficult for dealers to keep their lots stocked. That’s pushed up sticker prices in the new car market and nudged more shoppers toward preowned vehicles. Used car sales hit 3.4 million in April, up 58 percent from a year earlier.

Second, America’s supply of lightly driven Honda Civics has gotten snarled by trouble in the rental car industry. Ordinarily, corporations like Hertz and Enterprise sell millions of old cars and trucks back to dealers each year as they refresh their fleets. That’s not happening at the moment, because, rental companies already sold off a huge chunk of their fleets early on in the pandemic when nobody was traveling in order to raise cash and stay afloat. As a result, they’re now dealing with a shortage of cars on their own lots, which has sent rental prices in major vacation destinations zooming. Since new cars are scarce, some companies have even started buying used vehicles themselves. Instead of adding to dealers’ inventory, they’re competing for it.

As MacroPolicy Perspectives founder Julia Coronado points out, fewer cars are being repossessed than usual these days, likely thanks to the generous aid the government provided families to help them through the pandemic. That’s good news for households that need to get to work, but not so great for the auto market, since some dealers buy repossessed cars at auction in order to fix up and resell them.

And finally, I’ll add the obvious factor: stimmies. Americans got another round of checks from the government in March, and a lot of them probably decided to put them toward a new ride.

If you happen to be in the market for a car right now, this is all obviously very frustrating. The advice from experts is to avoid buying right now if you can. “If you don’t need that vehicle right now, just wait,” Ivan Drury, an analyst for car-shopping website Edmunds.com, told the Wall Street Journal recently. “You are not going to get anything you want, whether that be the price, the selection, or those little things that you really don’t want to compromise on.”

As for public policy? There’s obviously a lot of talk about inflation at the moment, and some Wall Street types are convinced the Federal Reserve should act quickly to stamp it out. And overall, prices rose by a fairly rapid 0.8 percent in April, up from 0.6 percent in March and 0.4 percent in February. But more than a third of that jump was due to used car and truck prices alone. Meanwhile, if you look at the Consumer Price Index minus food, shelter, fuel, and used vehicle prices—all of which have been batted around by the temporary forces of the pandemic—it’s up only 2.6 percent year over year, compared with 4.2 percent for all items. For consumers, that’s probably not going to offer a ton of solace at this precise moment. But raising interest rates in order to deal with temporary supply chain issues that are especially acute in a handful of sectors doesn’t make a lot of sense. Like America’s car shoppers, it’s fine for Jerome Powell & Co. to be patient and see if things settle.