Technically, the Supreme Court’s Thursday decision in Nestle v. Doe is a loss for human rights enforcement in the United States. The court ruled against six former child slaves who sued two major corporations for allegedly aiding and abetting their enslavement.* That outcome is no surprise. What is shocking is that the defendants failed to persuade the court to immunize all corporations from lawsuits under the Alien Tort Statute. Corporations bet big on Nestle v. Doe, apparently convinced that SCOTUS would use the case to abolish corporate liability under the ATS. Instead, five justices concluded that domestic corporations can be sued under the statute. Nestle thus hands a narrow loss to a half-dozen plaintiffs while opening the door to future litigation against corrupt, abusive, and lawless businesses.

The plaintiffs in Nestle allege that they were trafficked from Mali to the Ivory Coast as children, then forced to work on cocoa plantations under abominable conditions without pay. (Atrocities on these plantations are well known.) Nestle and Cargill didn’t own these plantations, but purchased their cacao and provided them with “financial and technical assistance.” The plaintiffs claim that both companies knew their suppliers were using child slaves, but declined to intervene because they valued the cheap prices. They accused these companies of “aiding and abetting” child slavery and sued them under the ATS, which gives federal courts the power to hear lawsuits filed by foreigners alleging a violation of international law.

Congress first passed the ATS in 1789, and the law was designed to provide remedies, including money damages, to noncitizens who suffer a “violation of the law of nations or a treaty of the United States.” In recent years, however, the Supreme Court’s conservatives have limited the scope of the law. The court has held that the ATS doesn’t apply to conduct that occurred outside the U.S., or to foreign corporations. When Neal Katyal, who represented Nestle and Cargill, argued this case at the Supreme Court, he urged the justices to further narrow the ATS by holding that it doesn’t apply to domestic corporations, either. He asserted that allowing corporate liability would “place U.S. firms at a competitive disadvantage” and “discourage foreign investment in the United States.”

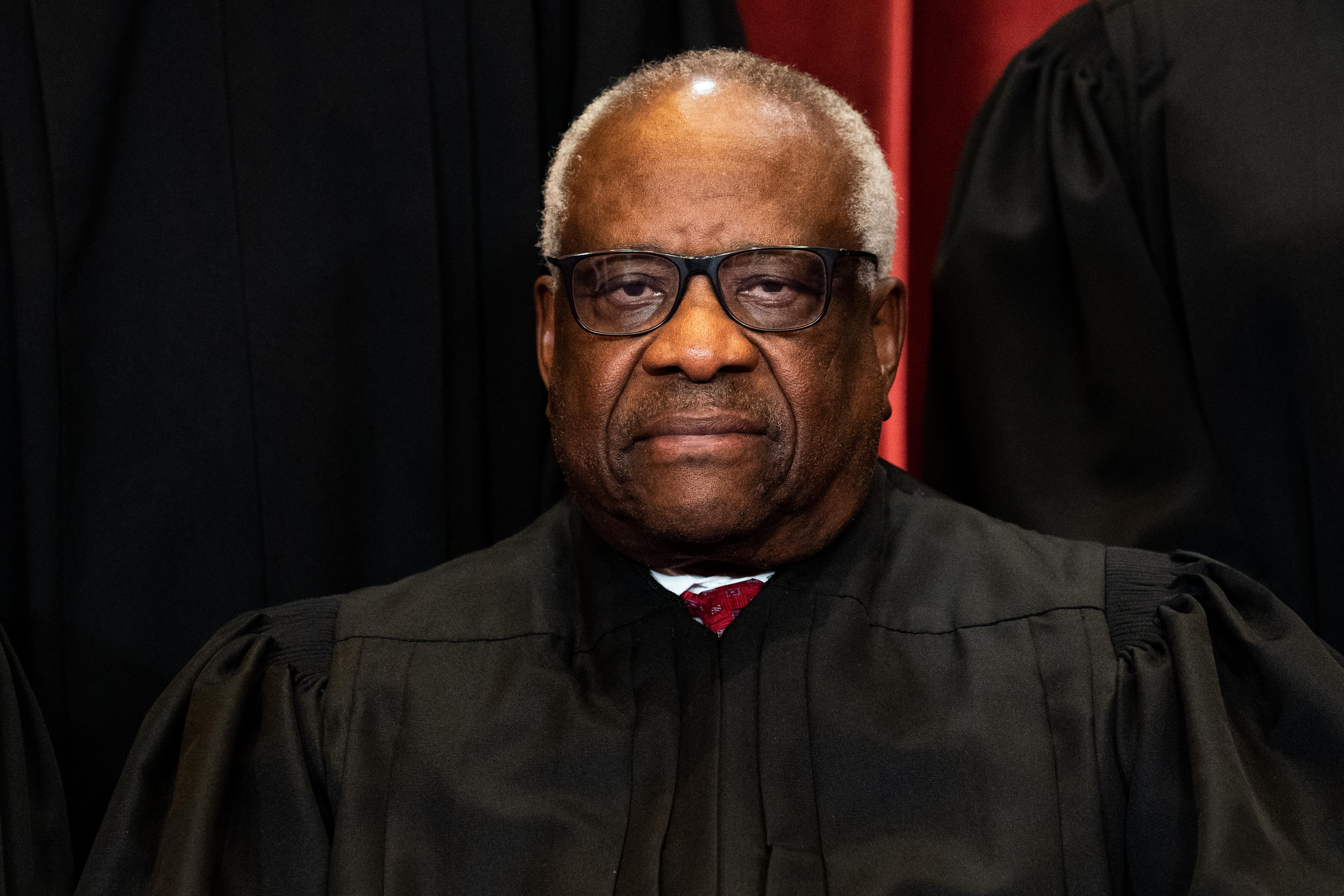

But the court refused to adopt Katyal’s position on Thursday. Instead, in a short opinion, Justice Clarence Thomas held that plaintiffs’ lawsuit focuses primarily on conduct that occurred overseas—the enslavement of children in the Ivory Coast. The court has already prohibited “extraterritorial application of the ATS.” This precedent, Thomas wrote, required the dismissal of the plaintiffs’ lawsuit.

Thomas’ majority opinion did not address corporate liability because it wasn’t necessary to resolve the case. But in three separate opinions, five justices declared that domestic corporations can be sued under the ATS. First, in a concurrence, Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote that nothing in the law “supplies corporations with special protections against suit.” Moreover, “nowhere does it suggest that anything depends on whether the defendant happens to be a person or a corporation.” He offered ample originalist evidence that the Congress of 1789 understood the law to place “corporations and individuals on equal footing when it comes to assigning rights and duties.” Gorsuch also noted that early ATS cases involved actions against ships, not people, which “underscores the ATS has never distinguished between defendants.”

Justice Samuel Alito joined this portion of Gorsuch’s opinion. He also wrote separately to reiterate his view that an ATS claim “may be brought against a domestic corporation.” Justice Sonia Sotomayor, joined by Justices Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan, also endorsed Gorsuch’s conclusion. “As Justice Gorsuch ably explains,” she wrote, “there is no reason to insulate domestic corporations from liability for law-of-nations violations simply because they are legal rather than natural persons.” Sotomayor pointed out that a majority of the court found that domestic corporations may be liable under the ATS.

The views of five justices expressed through three different opinions do not constitute binding precedent. But they do send a clear message to the lower courts that a majority of the Supreme Court is prepared to recognize this form of corporate liability. Judges who defy this quasi-holding in Nestle should be prepared for reversal at SCOTUS. And plaintiffs who suffered international law violations at the hands of American corporations are now on notice that the court may be amenable to their claims.

Nestle is not all good news. Thomas and Gorsuch, along with Justice Brett Kavanaugh, sought to narrow the crimes actionable under the ATS to just three: violation of safe conducts (meaning safe passage when traveling through a territory, usually during a conflict); infringement of the rights of ambassadors; and piracy. Alito did not endorse this view but praised the “strong arguments” behind it. Notably, though, Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Amy Coney Barrett declined to express any support for the other conservatives’ cramped vision of the law. (The liberal justices vigorously disagreed with it.) There were more votes in Nestle to apply the ATS to domestic corporations than there were to narrow the available causes of action.

Supreme Court decisions affirming the power of the ATS are few and far between. Nestle does not quite qualify. But it does open the courthouse door to victims of corporate malfeasance—an outcome favored by a cross-ideological coalition of justices. It is a shame that the plaintiffs won’t get a chance to argue their case in court. But by fighting all the way to the Supreme Court, they gave other victims of human rights abuses a renewed and unexpected hope for justice.

Correction, June 21, 2021: This article originally misstated that Nestle v. Doe was decided unanimously.