This summer’s spate of state-level bills aimed at censoring the content of history teaching in public school classrooms—bills that have made much of the supposed double threat of “critical race theory” and the New York Times’ 1619 Project—might seem somewhat random. But in fact, conservative attacks like these on humanities curricula that discuss race and racism in the United States follow a long-established pattern.

First, right-wing fears are always more about a vague idea of the content of such curricula than about classroom realities. (In Indiana, suburban parents have been “angered” by the supposed presence of critical race theory, or CRT—typically a graduate-level elective offered to law students—in their schools, despite the fact that their schools do not teach it.) Second, because activists on the right view the schools as the grease that makes slopes slippery, they tend to use school curricula to talk about a host of related social issues. (Anti-CRT activists lump together everything they don’t like, from Marxism to Black Lives Matter to progressive education, and call it CRT.) And third, these battles have always been waged over the stories that get told about the American past, present, and future. In that sense, the angry right wing is correct: The stakes couldn’t be higher.

Earlier battles over curriculum provided the template for today’s anti-CRT, anti–1619 Project political campaigns. In the late 1930s, for instance, activists in right-leaning patriotic groups such as the Daughters of the American Revolution and the American Legion warned their fellow Americans about a subversive set of textbooks. The fact that the textbooks written by Columbia professor Harold Rugg were widely popular and had been used for years in schools across America did not matter. The books, conservatives warned, represented an attempt by “radical and communistic textbook writers” to turn American children against America.

In reality, the books intended no such thing. Their lead author, Harold Rugg, an engineer turned professor of pedagogy whose intellectual roots lay in the Progressive education movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, took pains to categorically deny his participation in any communist or socialist movement. His vision of a good education, Rugg explained, consisted of “young people confronting social conditions and issues squarely and digging to the very roots of our changing culture.” Rugg hoped his books would lead students to think critically about the most difficult questions in American history, including racism and inequality. In his teachers’ guides, Rugg encouraged teachers always to ask students, “What do you think?”

Rugg published a series of historical textbooks that encouraged students to confront the country’s chronic problems of racism and class conflict—problems that loomed large in the collective consciousness during the Depression years, a time of great national stress. In Culture and Education in America (1931), Rugg denounced the “exploitative tradition” in American society. In a middle school textbook, Citizenship and Civic Affairs, he taught American children about “the question of equality and classes in America.” It was a harsh fact of American society and history, according to the book, that some people did not receive a fair reward for their hard work, while others got rich without much work at all. Embedded in those lessons was an idea that terrified conservatives of the 1930s. American children, they feared, would hear that U.S. history was not only a story of greatness but a story of struggle.

However, once the anti-Rugg campaign gained momentum among right-wing parents, what the books actually said mattered less than opponents’ stories about them. In Binghamton, New York, for instance, the school superintendent had read the books and liked them. As he told the press in 1940, “it’s the kind of book I want my children to have. To say it is subversive is absurd.” But the books’ reputation eclipsed all chances for reasonable debate. As one opponent declared, “I haven’t read the books, but—I have heard of the author, and no good about him.” To avoid “controversy,” the superintendent pulled them from the district’s schools. Elsewhere, school boards did more than just pull the books from their shelves. In towns from New Jersey to Wisconsin, panicked patriots lit bonfires of the books. Perhaps even worse, as historian Charles Dorn has found, other textbook writers censored themselves in order to avoid Rugg’s fate. The anti-Rugg crusaders, even if they did not know much about the actual Rugg textbooks, narrowed the curriculum and steered children away from any topic that might cause similar outrage.

The pattern of conservative backlash against progressive education’s approach to teaching social issues was well-established by the 1950s. Self-described patriotic groups like the American Legion and National Council for American Education warned of “unpatriotic” teachers and professors and wrung their hands about the “problem of making loyal Americans out of the boys and girls.” In a number of cases, these pressure groups managed to get textbooks deemed subversive pulled from schools. These groups were among many right-wing organizations that campaigned to purify American history textbooks of supposedly subversive ideas. Concepts identified as offensive included describing segregation as a problem or, in the words of one Florida legislator, touting the “superiority of the Negro race.”

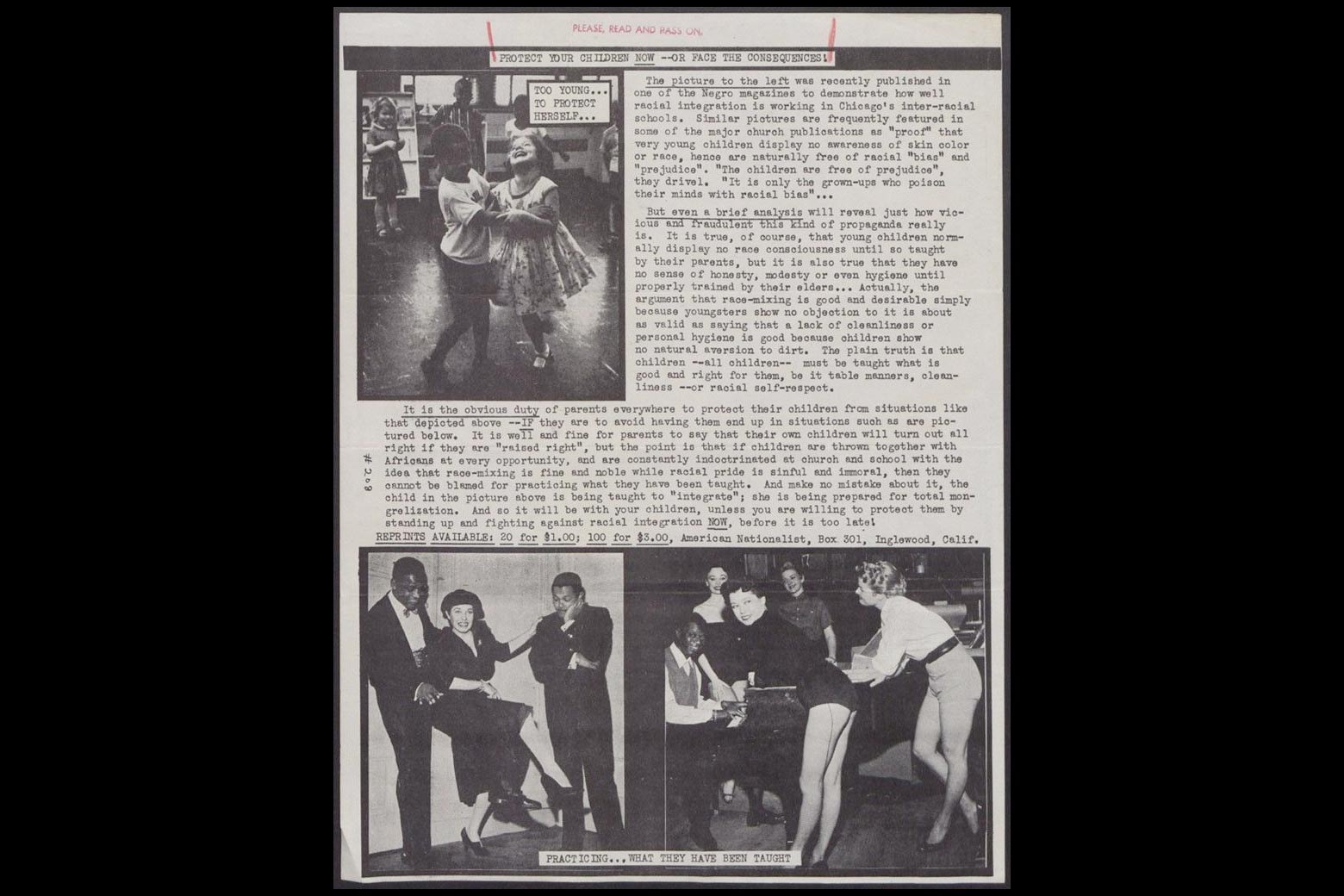

In the wake of Brown v. Board of Education, conservative groups predictably raged against school integration. But they also campaigned against curricula that would, in their view, upend white privilege and pride. The California far-right publication American Nationalist was typical when it warned against racially egalitarian ideas polluting white children’s minds. One of its pamphlets, which featured a photograph of a young white girl dancing with a Black classmate in Chicago, countered arguments, common among midcentury liberals, that children’s supposedly “natural” lack of hierarchical consciousness around race meant that teachers and curricula had the power to intervene to encourage a new way of thinking in the next generation. This youthful absence of prejudice, the writers argued, proved nothing. “It is true, of course,” the pamphlet explained, “that young children normally display no race consciousness until so taught by their parents, but it is also true that they have no sense of honesty, modesty, or even hygiene.”

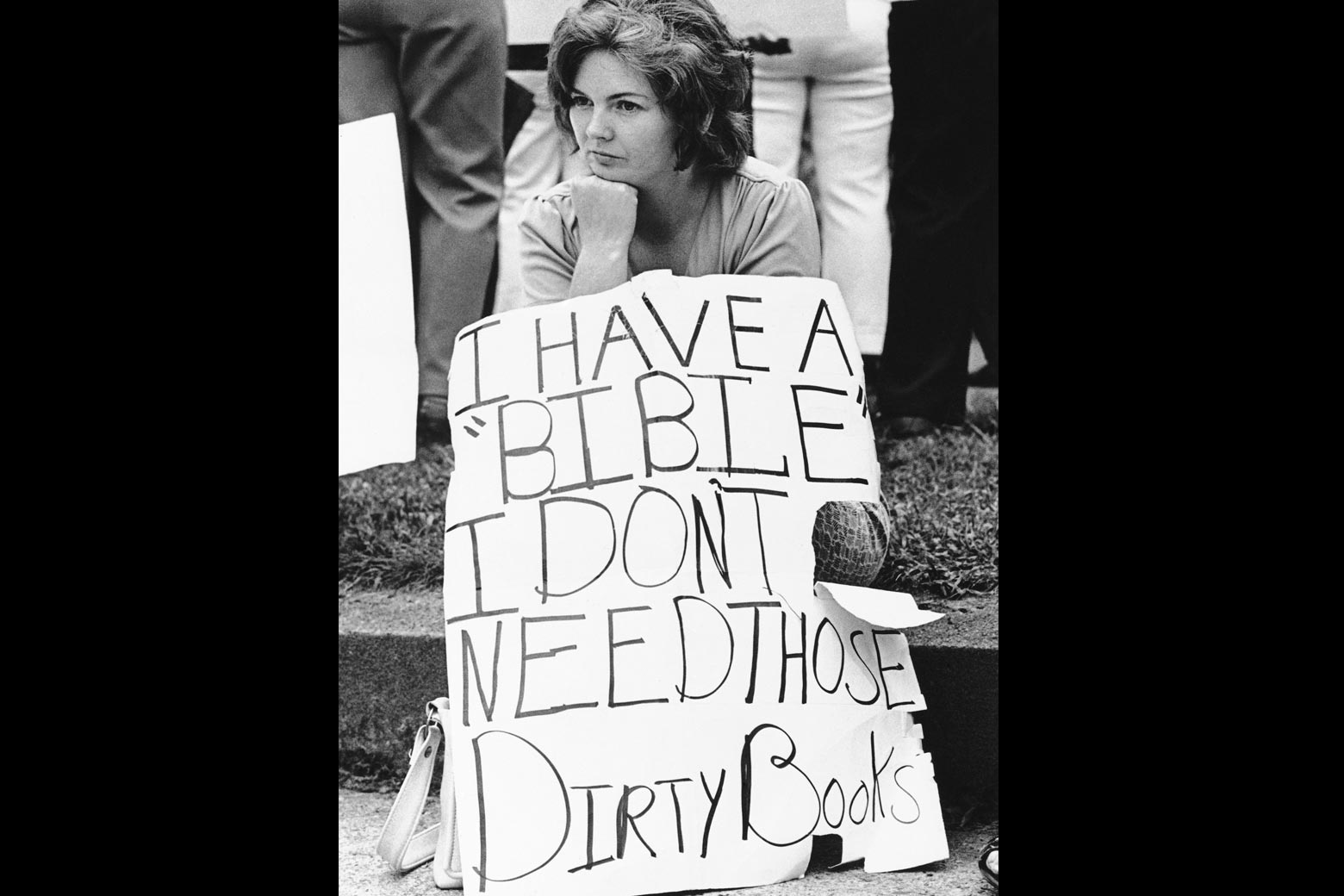

By the 1970s, backlash against supposedly progressive curriculums had ossified into predictable outcries about unpatriotic content, which often meant targeting material that dignified Black voices. Even if conservative complaints were rote, their activism was literally explosive. In Kanawha County, West Virginia, in 1974, white parents reacted with violent rage to false rumors about the contents of popular textbooks. In this case, a new series of English language arts textbooks had been approved by the state. One school board member, Alice Moore, warned that the books were full of anti-Christian, anti-American, anti-white propaganda and indoctrination.

These warnings stoked a fire that had been smoldering for decades. For weeks at the start of the 1974–75 school year, outraged parents boycotted the schools and their “dirty books.” Protesters shot and vandalized school buses. They threw firebombs into empty school buildings. They exploded a dynamite bomb at the school district headquarters. Their fury, once again, was only loosely connected to reality. In this case, protesters had circulated flyers at the picket lines, warning that the books were sexually graphic. Opponents also objected to the inclusion of excerpts of work by Black authors such as Eldridge Cleaver and George Jackson. By doing so, the textbooks—one conservative parent told a school board meeting—reduced the English language to “the language of the ghetto.”

Outraged white parents took to the streets to defend their children from exposure to such words and ideas. The supposed excerpts about sex were nowhere to be found in the actual textbooks under review. Still, protest leaders such as Alice Moore defended their opposition to Black authors. They were tired—as Moore said—of being called “racist” merely for “insist[ing] on the traditional teaching of English.” When it came to conservative outrage, the actual content of the books did not matter. As one boycott leader explained, “You don’t have to read the textbooks. If you’ve read anything that the radicals have been putting out in the last few years, that was what was in the textbooks.”

In addition to the immediate violence and destruction of the boycott, the Kanawha County campaign led to familiar long-term damage. Teachers censored themselves. As one teacher remembered, she and her colleagues were terrified by all the “chaos.” Another teacher remembered checking with her principal before she taught a lesson in biology class about the asexual reproduction of mollusks. She did not want to be accused of warping young minds about sex. Teachers stopped teaching books such as 1984 and Brave New World, on the off chance that someone might find them too controversial.

Today’s backlash against the alleged teaching of critical race theory in America’s schools, like these earlier flare-ups over humanities curricula, holds the same potential to curb honest reckonings with the American past and present. As with prior reactionary movements, opponents of CRT maintain that American history is not meant to be merely another set of facts for children to learn. Instead, history must be a well of inspiration, a pure source of greatness from the past. From this perspective, CRT is any dangerous drop of doubt that will contaminate comforting white fantasies about America’s past, present, and future.

Classes in subjects that include the history of race and racism might be banned or canceled, due to the chilling effect of the backlash; some schools have already gone there. Even worse, teachers and students may resort to a stultifying self-censorship, avoiding topics that are vitally important precisely because they help students understand the true contours of America’s troubled history. It’s impossible to face history if teachers are always looking over their shoulders. And for those cynically leading the charge against CRT, that’s precisely the point.