Most of the attention focused on Facebook this week has centered on the company’s oversight board and its decision to permit the platform’s ban of Donald Trump. Meanwhile, a weirder controversy about Facebook’s ads and privacy policies has been playing out between the social media giant and encrypted messaging service Signal. Signal initiated the spat on May 4 when Jun Harada, the company’s head of growth and communication, posted on the Signal blog about a set of ads that Harada said Signal had tried to run on Instagram. Instead, Facebook blocked the ads and shut down Signal’s advertising account.

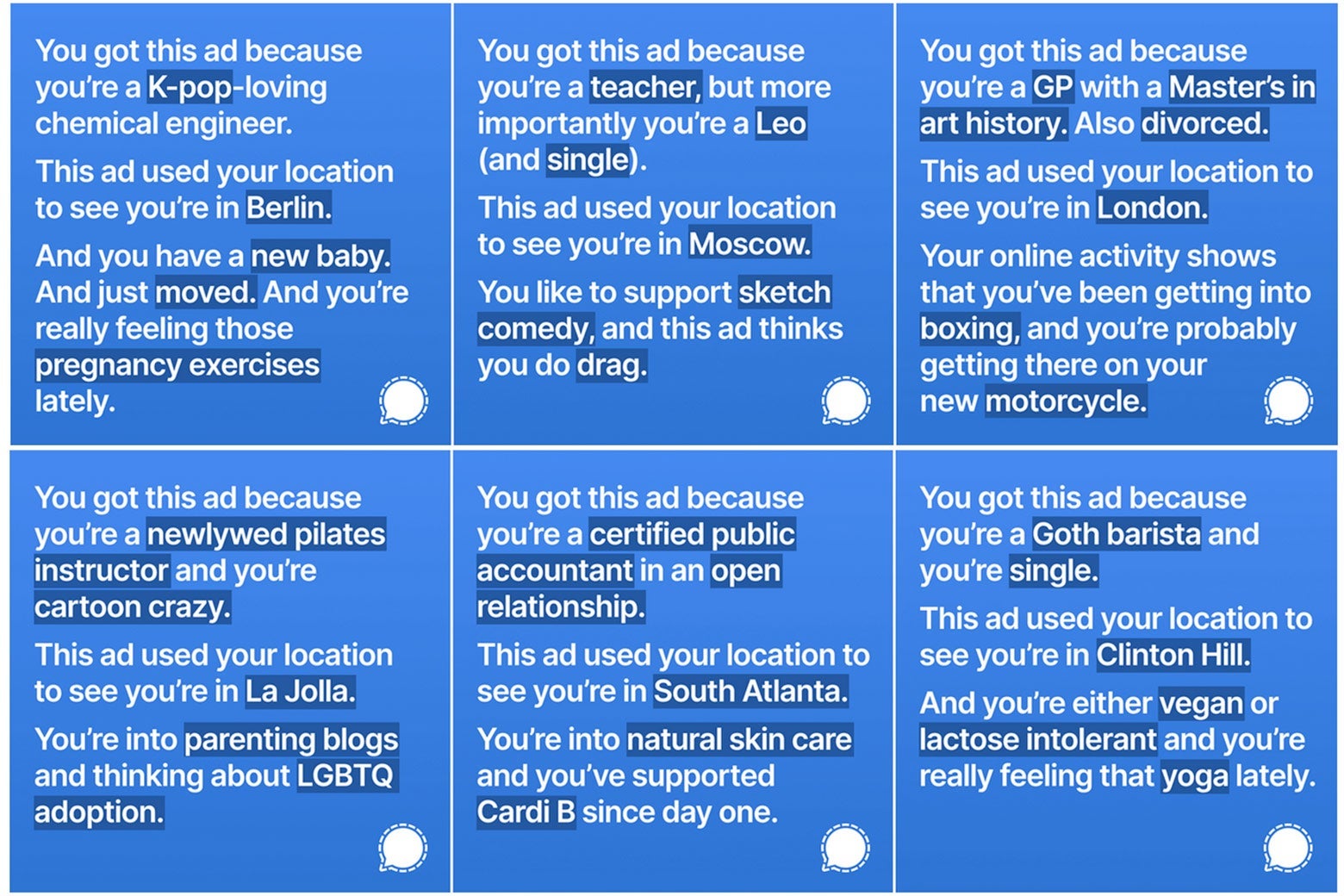

The ads themselves were designed to promote Signal’s end-to-end encryption by highlighting how much data other companies, like Facebook, collect about their users. In screenshots published with Harada’s post, the ads are tailored to the individuals viewing them by using details ostensibly provided through Facebook’s own advertising platform. So, one example ad in the blog post reads: “You got this ad because you’re a teacher, but more importantly you’re a Leo (and single). This ad used your location to see you’re in Moscow. You like to support sketch comedy, and this ad thinks you do drag.” Another informs the reader “You got this ad because you’re a K-pop-loving chemical engineer. This ad used your location to see you’re in Berlin. And you have a new baby. And just moved. And you’re really feeling those pregnancy exercises lately.”

Harada wrote that by using the information that Facebook collects to target ads in the ads themselves, Signal was hoping to “show you the personal data that Facebook collects about you and sells access to.” It’s a clever way to use Facebook’s own advertising infrastructure to highlight just how much the platform knows about users. In fact, that lack of clarity is exactly why many data protection regulations and rules have focused on transparency requirements for companies that collect and process data—so that their customers know exactly what is being collected and why and have the ability to access that data themselves.

But downloading a large file of all the information Facebook has collected about you (which you can do!) is probably not something that most people are going to bother with, much less combing through it. So catchy, highly visible representations of that data like the mocked-up Signal ads are an interesting and potentially valuable tool for raising people’s awareness about their digital privacy. It’s no wonder that Facebook would be unhappy with them.

Except that, according to Facebook, Signal never actually tried to place those ads on Instagram. In response to the post, Facebook issued the following statement: “This is a stunt by Signal, who never even tried to actually run these ads—and we didn’t shut down their ad account for trying to do so. If Signal had tried to run the ads, a couple of them would have been rejected because our advertising policies prohibit ads that assert that you have a specific medical condition or sexual orientation, as Signal should know. But of course, running the ads was never their goal—it was about getting publicity.”

In response, Signal then tweeted: “We absolutely did try to run these. The ads were rejected, and Facebook disabled our ad account. These are real screenshots, as Facebook should know.” The tweet was accompanied by two screenshots showing that a Facebook ad account had been disabled. Facebook spokesperson Joe Osborne replied (again on Twitter) that the screenshots were “from early March, when the ad account was briefly disabled for a few days due to an unrelated payments issue.” And reiterated, “The ads themselves were never rejected as they were never set by Signal to run. The ad account has been available since early March, and the ads that don’t violate our policies could have run since then.” Indeed, Facebook has permitted some very specific ads that make use of the company’s data on individuals in the past. For instance, t-shirt company Solid Gold Bomb notably advertised personalized t-shirts to Facebook users featuring slogans customized using their personal details (e.g., “Never Underestimate A Woman Who Loves Stephen King And Was Born In April,” or “I’m a VET who EATS BEEF and sings KARAOKE.”)

The back-and-forth between Facebook and Signal is so bizarre that it’s hard to know what to make of it. Clearly, one company is lying (or, at the very least, stretching the truth) about what happened, but why? Returning to the original Signal blog post, it’s striking (to me, at least) that Harada never quite comes right out and says that Facebook blocked the ads or disabled Signal’s ad account, though the post definitely heavily implies that that’s what happened. For instance, Harada wrote: “We wanted to buy some Instagram ads. … The ad would simply display some of the information collected about the viewer which the advertising platform uses. Facebook was not into that idea.” And following that sentence was a screenshot of an ad account having been disabled. A later sentence reads: “Being transparent about how ads use people’s data is apparently enough to get banned; in Facebook’s world, the only acceptable usage is to hide what you’re doing from your audience.”

But nowhere in the post does Harada say explicitly that Signal actually did try to buy these ads or end up having its account blocked. On the other hand, the later May 4 tweet from the Signal Twitter account says explicitly that the company tried to run the ads and they were rejected and resulted in Signal’s ad account with Facebook being disabled. That makes it hard to write this all off as a big misunderstanding or a misleading blog post that stretched a hypothetical situation. It’s a strange reminder of just how hard it is to know who to trust when it comes to online privacy—and also how complicated these issues really are.

It’s true that if Signal had tried to run these ads, some of the sample ones they included in their blog would seem to violate Facebook’s policy on ads not containing any “personal attributes,” including assertions about “a person’s race, ethnic origin, religion, beliefs, age, sexual orientation or practices, gender identity, disability, medical condition (including physical or mental health), financial status, voting status, membership in a trade union, criminal record, or name.” So, for instance, according to Facebook’s own guidelines, it’s OK to include in an advertisement the line “Find Black singles today” but not “Meet other Black singles near you” and fine to advertise “Depression counseling” but not permitted to say in an ad, “Treat your anxiety with these helpful meditations.” I can understand some of Facebook’s rationale for keeping these attributes out of advertisements—the possibility that other people might see those ads, for instance, and learn personal details by accident or form incorrect assumptions. And if Signal is lying about being blocked from running these ads, I can certainly understand Facebook’s frustration about being criticized for something it didn’t do.

But I also think that the best way Facebook could respond to this whole strange saga, instead of fighting with Signal on Twitter, would be to steal this idea and run these ads (or some version of them, probably minus the Signal logo) themselves to make clear to their users just how many personal details they know—and how truly transparent they’re willing to be about that knowledge.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.