Performance perception: The effect of late-loading banners

By Gilles Dubuc, Senior Software Engineer, Wikimedia Performance Team

However, while we don’t have ads, we do display announcement and fundraising banners frequently at the top of wikis. Here’s an example:

Those are driven by JS and as a result always appear after the initial page render. Worse, they push down content when they appear. This is a long-standing technical debt issue that we hope to tackle one day. One of the most obvious issues we deal with that may impact performance perception. How big is the impact? With our performance perception micro survey asking our visitors about page performance, we can finally find out.

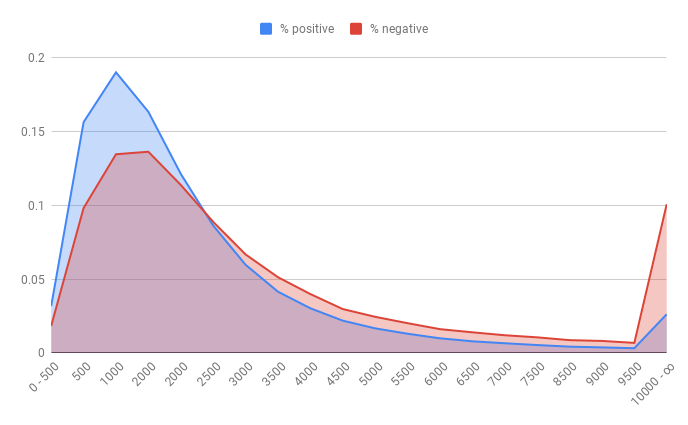

Perception distribution

We can look at the distribution (Y axis) of positive and negative survey answers based on when the banner was injected into the DOM, in milliseconds (X axis).

We see the obvious pattern that positive answers to the micro-survey question (did this page load fast enough?) are more likely if the banner appeared quickly. However, by looking at the data globally like this, we can’t separate the banner’s slowness from the page’s. After all, if your internet connection and device are slow, both the page itself and the banner will be slow, and users might be responding based on the page, ignoring the banner. This distribution might be near identical to the same being done for page load time, regardless of a banner being present or not.

Banner vs no banner

A simple way to look at this problem is to check the ratio of micro-survey responses for pageviews where a banner was present vs pageviews where there was no banner. Banner campaigns tend to run for specific periods, targeting certain geographies, meaning that a lot of visits don’t have a banner displayed at all. Both samples sizes should be enough to draw conclusions.

| Corpus | User satisfaction ratio | Sample size |

| No banner or answered before banner | 86.64% | 1,111,542 |

| Banner and answered after banner | 87.8% | 311,332 |

For the banner case, we didn’t collect whether the banner was in the user’s viewport (i.e. was it seen?).

What is going on? It would seem that users are slightly more or equally satisfied of the page performance when a banner is injected. It would suggest that our late-loading banners aren’t affecting page performance perception. This sounds too good to be true. We’re probably looking at data too globally, including all outliers. One of our team’s best practices when findings that are to good to be true appear is to keep digging to try to disprove it. Let’s zoom in on more specific data.

Slow vs fast banners

Let’s look at “fast” pageloads, where loadEventEnd is under a second. That event happens when the whole page has fully loaded, including all the images.

| Corpus | User satisfaction ratio | Sample size |

| Banner injected into DOM before loadEventEnd | 92.66% | 4,761 |

| Banner injected into DOM less than 500ms after loadEventEnd | 92.03% | 67,588 |

| Banner injected into DOM between 2 and 5 seconds after loadEventEnd | 85.33% | 859 |

We can see that the effect on user performance satisfaction starts being quite dramatic as soon as the banner is really late compared to the speed of the main page load.

What if the main pageload is slow? Are users more tolerant of a banner that takes 2-5 seconds to appear? Let’s look at “slow” pageloads, where loadEventEnd is between 5 and 10 seconds:

| Corpus | User satisfaction ratio | Sample size |

| Banner injected into DOM before loadEventEnd | 79.13% | 3019 |

| Banner injected into DOM less than 500ms after loadEventEnd | 78.45% | 2488 |

| Banner injected into DOM between 2 and 5 seconds after loadEventEnd | 76.17% | 2480 |

While there is a loss of satisfaction, it’s not as dramatic as for fast pages. This makes sense, as users experiencing slow page loads probably have a higher tolerance to slowness in general.

Slicing it further

We’ve established that even for a really slow pageload, the impact of a slow late-loading banner is already visible at 2-5 seconds. If it happens within 500ms after loadEventEnd, the impact isn’t that big (less than 1% satisfaction drop). Let’s look at the timespan after loadEventEnd in more detail for fast pageloads (< 1s loadEventEnd) in order to find out where things start to really take a turn for the worse.

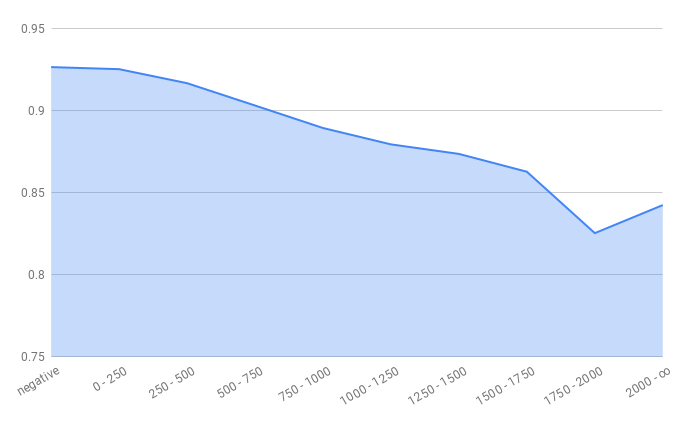

Here’s the user page performance satisfaction ratio, based on how long after loadEventEnd the banner was injected into the DOM:

Conclusion

The reason why the issues caused by late-loading banners when looking at data globally is probably because most of the time banners load fast. But when they happen after loadEventEnd, users start to be quite unforgiving, with the performance satisfaction ratio dropping rapidly. For users with an otherwise fast experience, we can’t afford for banners to be injected more than 500ms after loadEvendEnd if we want to maintain a 90% satisfaction ratio.

Of course, we would like to change our architecture so that banners are rendered server-side, which would get rid of the issue entirely,. But in the meantime loadEventEnd + 500ms seems like a good performance budget we should aim for if we want to mitigate the user impact of our current architectural limitations.

About this post

This post was originally published on the Wikimedia Performance Team Phame blog.

Featured image credit: KC Ballet KC Ballet 14-15 Alice-Rabbit, KCBalletMedia, CC BY 2.0