Supported by

Art Review

A Man of Contradictions, With a Collection to Match

When China’s last emperor finally left the premises in 1924, the Forbidden City was renamed the Palace Museum, and a labyrinthine complex of ceremonial and domestic spaces, off limits to all but a few for centuries, was suddenly open to the world.

Still, it kept some secrets. Few visitors, for example, knew of the existence of a self-contained suite of small pavilions and gardens tucked away at the Forbidden City’s northeast corner, echoing its shape.

They made up the Tranquillity and Longevity Palace, which, in the mid-18th century, had been remodeled as a potential retirement home by the adamantly unretiring and design-obsessed Qing dynasty emperor Qianlong.

He lavished attention on the palace — covered its walls with trompe l’oeil paintings, fitted it out with false doors, see-through partitions, Buddhist shrines and clocks — to make it a place that reflected his adventurous tastes, a place where he might want to live. But in the end, he spent little time there. And the palace, often referred to now as the Qianlong Garden, had only a handful of imperial tenants after he died in 1799.

For most of the 20th century it stayed empty. The Chinese government had no cash to spare for its upkeep, and conserving Qing culture was on no one’s list of priorities. The building exteriors were maintained, but the interiors, with their frozen-in-time ensembles of furniture, painting, textiles and luxury objects, were left to fend for themselves.

Things have changed. China, now (and not for the first time) a global power in need of an agreeable self-image to sell, has seen the wisdom of preserving its visual heritage — all of it. And international scholars of that heritage, once separated by distance, are now thoroughly networked. A concrete result of this new one-worldism is a collaboration, now in progress, between the Palace Museum and the World Monuments Fund to restore the Qianlong Garden to its former splendor.

Among the art historians acting as consultants to the project is Nancy Berliner, the curator of Chinese art at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Mass. By 2003, the year the restoration got under way, Ms. Berliner had already scored a Qing-related coup of her own by overseeing the transfer, from China to the Salem museum, of an intact house dating to the dynasty. And last fall she scored a second one with “The Emperor’s Private Paradise: Treasures From the Forbidden City,” an exhibition she organized for the Peabody Essex, and which now appears, in a different form, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

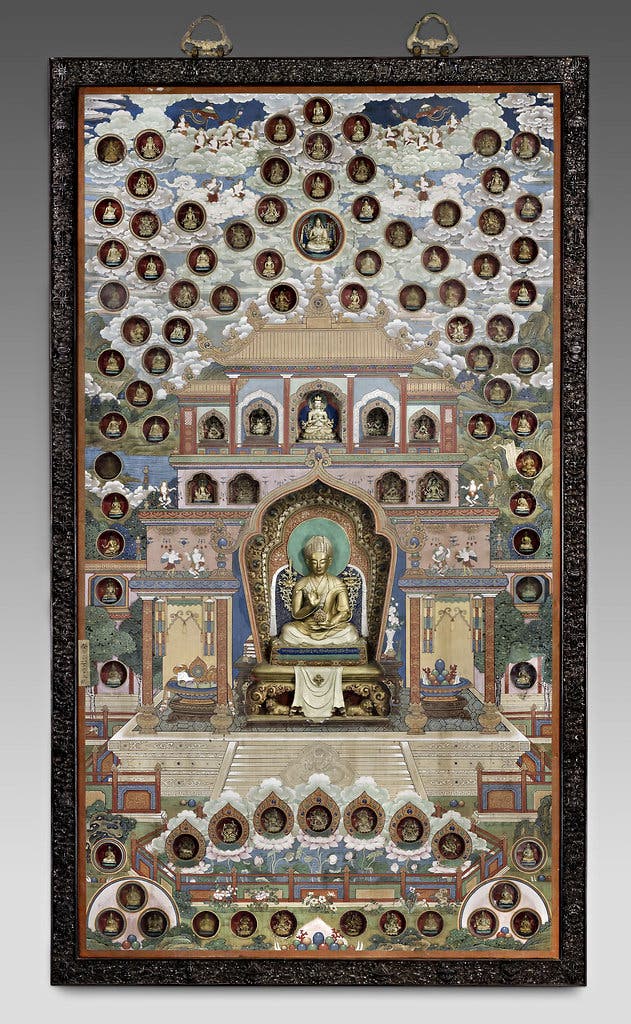

The show is made up primarily of freshly conserved Qing objects — thrones, cabinets, screens, religious sculptures, paintings — from the collection of the Palace Museum, many specifically from Qianlong Garden buildings. Qianlong himself probably commissioned some of the items. Certainly his sensibility is written all over them.

Born in Beijing in 1711, Qianlong (pronounced Chee-en lohng) descended from non-Chinese-speaking northerners who called themselves Manchu and ruled China as the Qing dynasty from 1644 to 1911. Self-confident and adventurous, he was a ceaseless mover and doer, constantly making inspection tours of a country that during his reign was the largest and richest in the world.

Largeness, in fact, was his calling card. His cultural initiatives seem conceived precisely to generate preposterous statistics. He commissioned and participated in the creation of an anthology of 2,000 years of Chinese literature: it appeared in the form of 36,000 handwritten volumes, which he ordered to be copied several times.

A writer himself, he left more than 40,000 poems behind when he died. When he was 50, he published a compendium of his calligraphy. He acquired art of all kinds in record-breaking quantities. At one point he cataloged a collection of some 10,000 of his paintings, then went on to collect more.

He was a knot of contradictions. He preserved thousand of books in his anthology, but also destroyed thousands, some of them legendary classics, that he considered politically subversive. As an art connoisseur, he had an uncannily sensitive eye, yet he insisted on incising his name into precious ceramics and writing it repeatedly on priceless paintings, effectively defacing them.

Although he had many self-portraits made, no cohesive reading of his personality can be drawn from them. In one painting he is an imposing Confucian ancestor figure; in another, a humble young Daoist scholar. In a third piece we find him floating at the center of a Tibetan Buddhist mandala as the embodiment of the bodhisattva of wisdom, which he believed himself to be.

As a highly self-aware performer, he exploited the public relations uses of shape-shifting, offering alternate versions of himself to different audiences, Manchu, Han Chinese and European.

He was wary of Europe politically, but entranced by vision-tickling aspects of its art, like vanishing-point perspective and trompe l’oeil realism. Christianity left him cold — why should he worship a supreme being when he was one? — but he treasured Jesuit missionary artists like Giuseppe Castiglione and kept them on his payroll.

Contradiction is also the animating dynamic of the art in the Met show created to adorn the various buildings — reception halls, studios, libraries, Buddhist shrines — in the Qianlong Garden.

In the circular portrait of the young Qianlong in scholar robes in the first gallery, the pictorial space is pancake-flat, depthless. But in a Western-style mural painting on silk nearby, life-size figures of woman and child beckon us into a three-dimensional hall. (Several such murals cover walls in the one Qianlong Garden building that was fully restored in 2008 and can be digitally toured in another Met gallery.)

Realism in Qing art, however, often veers into the surreal, as is evident in a mesmerizingly bizarre furniture ensemble. Like some version of rustic Victoriana, all three units — chair, couch bed, foot stool — appear to be woven from roots and vines, though in this case the interwoven strands look freakishly alive, writhing and twisting like nests of snakes. Only when you inspect the furniture closely do you see that this organicism run riot is strictly an illusion. The roots and vines have been painstakingly puzzled together from many small pieces of wood, in a design meant to evoke a Daoist immersion in nature.

‘The Emperor’s Private Paradise’

8 Photos

View Slide Show ›

This kind of interplay between opposites — the unnatural and the natural, the grotesque and the spiritual — powers the show. Qianlong went for art and design that pushed such contrasts to the limit and beyond, short-circuiting received notions of good taste and bad taste to deliver little shocks of pleasure.

You can feel such zaps radiating from one work in particular: a 16-panel wood-and-lacquer screen carrying portraits of early disciples of the Buddha, known as luohans. These figures are traditionally pretty gross: ragged and repellent old men, with cartoon faces and hair sprouting from unlikely places. They’re shown that way here too, but in a medium — white jade inlaid on black lacquer — that is so ethereal, and worked with such fineness, as to all but cancel out any impression of ugliness.

The screen holds another surprise too. When conservators moved it from its original position against a wall, they found that the reverse sides of the panels were painted with images of trees and flowers in tones of gold. Stunning!

At the Peabody Essex, the screen was free-standing and could be viewed from both sides. The Met, by contrast, has placed it in a long wall case, with the luohans face out, and a few panels flipped to give a sampling of the painting. And this is just one of the ways in which the Met edition of the show differs from the Salem original.

Judging from photographs, you can see that the installation Ms. Berliner devised at the Peabody Essex was spaciously laid out, with an effort made to simulate the architectural interior in which the objects were once found. At the Met, the same objects have been squeezed into the narrow Chinese painting galleries, with almost everything confined to tall cases designed to hold scrolls.

As if to compensate for a more straightened and prosaic approach, the New York presentation — organized by Maxwell K. Hearn, curator of Chinese art, with an ingenious design by Daniel Kershaw — has been enriched with examples of Qing art from the Met’s collection, including a large Castiglione drawing and a pair of panoramic scrolls depicting two of Qianlong’s imperial road trips.

We also get something that in most museums we can only imagine: a real garden, in the form of the Astor Court. It’s based on a Ming rather than a Qing prototype, but the components — twisty river rocks set in greenery — are right. And, because the Met’s display cases are as shallow as they are tall, we can see everything in them close-up: the cloisonné medallions adorning a doorway surround, the stitch work in a satin chair cover, the chips of jade, coral and lapis lazuli embedded in a relief of a blossoming plum tree that comes across as both garish and sumptuous.

Up close was the emperor’s perspective too: proprietary, absorbed, evaluative. And — who knows? — it may not be available again, once these objects return to Beijing and are placed, where they belong, in the completely restored Qianlong Garden that is scheduled to reopen in 2019, to what will surely be an avid new public.

Forbidden-City Treasure

WHAT “The Emperor’s Private Paradise: Treasures From the Forbidden City.”

WHEN AND WHERE Through May 1, Metropolitan Museum of Art; (212) 535-7710, metmuseum.org.

Advertisement