Income mobility

American genes, European culture?

Jan 23rd 2012, 16:49 by M.S.

A PROPOS of the argument over statistics showing that intergenerational income mobility in America is lower than that in most of Europe, Tyler Cowen hypothesises:

Why do many European nations have higher mobility? Putting ethnic and demographic issues aside, here is one mechanism. Lots of smart Europeans decide to be not so ambitious, to enjoy their public goods, to work for the government, to avoid high marginal tax rates, to travel a lot, and so on. That approach makes more sense in a lot of Europe than here. Some of the children of those families have comparable smarts but higher ambition and so they rise quite a bit in income relative to their peers. (The opposite may occur as well, with the children choosing more leisure.) That is a less likely scenario for the United States, where smart people realize this is a country geared toward higher earners and so fewer smart parents play the “tend the garden” strategy. Maybe the U.S. doesn’t have a “first best” set-up in this regard, but the comparison between U.S. and Europe is less sinister than it seems at first. “High intergenerational mobility” is sometimes a synonym for “lots of parental underachievers.”

Among the unexamined assumptions here is the notion that "smarts" are innate, while "ambition" is environmentally determined. Actually, it's more than that: "smarts" are assumed to be both innate and inherited, while "ambition" is not inherited, but appears to be sometimes environmentally influenced (ie, Europeans are less ambitious than Americans) or sometimes individually varying for unknown reasons (ie, some European children become more ambitious than their parents, for unspecified reasons, even though their overall environment is not ambitious). Why would we believe this to be the case?

Among the unexamined assumptions here is the notion that "smarts" are innate, while "ambition" is environmentally determined. Actually, it's more than that: "smarts" are assumed to be both innate and inherited, while "ambition" is not inherited, but appears to be sometimes environmentally influenced (ie, Europeans are less ambitious than Americans) or sometimes individually varying for unknown reasons (ie, some European children become more ambitious than their parents, for unspecified reasons, even though their overall environment is not ambitious). Why would we believe this to be the case?Another issue I have with this hypothetical mechanism is that it posits that the reason Europeans are more likely to switch income categories is that fewer of them are trying to switch income categories. It makes sense that an ambitious person might find it easier to move up the income ladder in a society where most others weren't so ambitious. But if you measure the overall income mobility of the society, it seems like the easiness for a given ambitious person will be canceled out by the widespread lack of ambition that made it easy in the first place. This idea seems to me to suffer from a nobody-goes-there-it's-too-crowded problem.

Finally, returning to the innateness of "smarts", it's a truism that variance in characteristics is more due to innate/genetic reasons when the external environment is more homogenous. For example, if two tulips are raised in identical circumstances, then all the variation in observed characteristics will be due to genetic differences, whereas if one tulip is given more light than the other, much of the variation will be due to environmental factors. In the northern European countries that show higher intergenerational mobility than America does, the quality of the school systems is far more homogenous than in America. Schools for poor Dutch and Swedish kids are much better than schools for poor American kids. If income is dependent on innate "smarts", this should mean that more, not less, of the observed variation in Dutch and Swedish incomes is due to innate smarts. In America, meanwhile, more of the observed difference in incomes should be due to the environmental influence of having attended rich or poor schools. To put it in plain language, if you think smarts are innate but ambition is learned, and you know school quality in America varies widely on income lines while schools in Sweden vary less, and you know there's more intergenerational mobility in Sweden, then your conclusion would be that poor kids in America go to lousy schools where they aren't taught how to be ambitious (rich kids go to good schools and are), while poor kids in Sweden are being taught how to be ambitious but end up with different incomes due to their varying innate smarts.

Now let's recall why we were having this argument in the first place. Progressives have been arguing that massive and growing income inequality in America is a moral problem. Conservatives have responded that it's not a moral problem, because America is the land of opportunity: those increasingly disadvantaged poor people can rise up and become rich if they try hard enough. Progressives responded that this isn't true, actually America has less income mobility than most other rich countries, and there's more income mobility in societies that are less unequal. Now Mr Cowen responds that, while there may be more income mobility in other countries, this could be because in America all the smart people are extremely ambitious, so income differentials basically reflect innate differences in ability and there's no way for poor people to move up the income ladder even if they are ambitious. If this were true, and for the reasons outlined above I think it's not, then the argument is that massive and growing income inequality in a society where poor people have relatively little hope of advancing themselves no matter how hard they try is not a moral problem because...?

(Image credit: Ssolbergj)

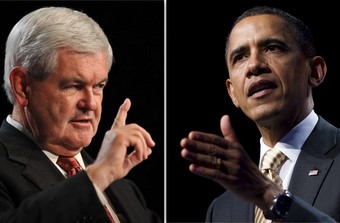

Gingrich's win

Newt presses those good ol' buttons

Jan 23rd 2012, 13:47 by M.S.

SOMETHING happened over the course of the past week that moved Newt Gingrich from a relevancy-challenged 15 points behind Mitt Romney in South Carolina to a dominant 40-to-28 win. What was it? The New York Times' exit polling doesn't give many answers. More than half of voters made their choice within a few days of the primary, but that was obvious from the swing in the polls. More significantly, "Six in 10 voters said it was important that a candidate shared their religious beliefs, and nearly half of them backed Mr. Gingrich, who has converted to Catholicism; about a fifth went for Mr. Romney, a Mormon." As my colleague writes, it looks like the Mormon factor is important, at least in heavily evangelical states. But that's a static issue; Mitt Romney wasn't any less Mormon a week ago, when he had a dominant lead, than he was on Saturday, when he got crushed. This seems like a better explanation:

For nearly two-thirds of voters, the recent debates were an important factor in their decision; for about 1 in 8 they were the most important factor. Mr. Gingrich was considered by many to have done particularly well in the debates; he received the votes of about half of those for whom the debates were important.

Newt Gingrich did two major things in the past ten days. The first was to launch a blistering attack on Mitt Romney as a greedy "vulture capitalist" who doesn't care about American jobs. The second was to turn in a confident, aggressive performance in two debates. And what was it that so impressed audiences about those debates? Was it Mr Gingrich's big ideas for the future? That seems doubtful, largely because, as Ross Douthat writes, it's not clear what they are.

I have, for my sins, watched Gingrich make his pitch across what feels like seventeen thousand Republican primary debates, and I am at a loss to identify the “big ideas” and “big solutions” that he is supposedly campaigning on. Yes, he has an implausible supply-side tax plan, but you never hear him talk about it. He has technically signed on to some form of entitlement reform, but you never hear him talk about that, either. Instead, so far as I can tell, his “idea-oriented” campaign consists almost entirely of promising to hold Lincoln-Douglas-style debates with President Obama, grandstanding about media bias and moderator stupidity, defending his history of ideological flexibility much more smoothly than Mitt Romney, and then occasionally throwing out a wonky-sounding notion (like, say, outsourcing E-Verify to American Express) that’s more glib than genuinely significant. His last-minute momentum in South Carolina, which last night’s debate did nothing to derail, has been generated almost exclusively by the politics of ressentiment: If he wins the Palmetto State primary, it will be because conservative voters don’t much like the mainstream press, and Gingrich has mastered the art of taking tough questions and turning them into dudgeon-rich denunciations of the liberal media and all its works.

Mr Douthat thinks Mr Gingrich's success here hinges on his denunciation of the liberal media. I think the ressentiment here is actually more specific than that, and it sits significantly deeper. Mr Gingrich scored big on two points. The first was his insistence on terming Barack Obama the "food-stamp president"; my colleague is right to term this "expert racial dog-whistling". The second was the thunderous counter-attack against his disgruntled ex-wife's allegation that before their divorce 13 years ago, he had asked for an open marriage so that he could continue the affair he had begun with his then legislative aide, now his wife.

In the debates, in other words, Newt Gingrich hit two themes hard. The first was to link our black president with food stamps (and against hard work), and to angrily denounce the suggestion by a black media moderator that this could possibly be considered racial exploitation. The second was to blast the media for paying attention to his ex-wife's account of an extramarital affair. How might we characterise these themes? What is it about these two themes that makes them so appealing to the Republican voters who helped Mr Gingrich gain over 25 points on Mr Romney in ten days? I leave this exercise to the reader.

Slideshow

Shifting sands in the Republican race

Jan 22nd 2012, 15:54 by The Economist online

-

With the departures of both Jon Huntsman and Rick Perry, only four Republican candidates remained in the race for the nomination.Christopher Fitzgerald

With the departures of both Jon Huntsman and Rick Perry, only four Republican candidates remained in the race for the nomination.Christopher Fitzgerald -

In both of South Carolina's presidential debates, at Myrtle Beach and later in North Charleston, the other candidates turned up the heat on the front-runner, Mitt Romney.Christopher Fitzgerald

In both of South Carolina's presidential debates, at Myrtle Beach and later in North Charleston, the other candidates turned up the heat on the front-runner, Mitt Romney.Christopher Fitzgerald -

Mitt Romney appeared at Wofford College in Spartanburg.Christopher Fitzgerald

Mitt Romney appeared at Wofford College in Spartanburg.Christopher Fitzgerald -

Darrin Goss, a freshman at the college was still undecided about how he would vote. He described the state of the jobs market as "not hopeful".Christopher Fitzgerald

Darrin Goss, a freshman at the college was still undecided about how he would vote. He described the state of the jobs market as "not hopeful".Christopher Fitzgerald -

Michele Sullivan, 32, said she was concerned about the cost of medical insurance.Christopher Fitzgerald

Michele Sullivan, 32, said she was concerned about the cost of medical insurance.Christopher Fitzgerald -

Always immaculately coiffed herself, Callista Gingrich double-checked her husband before his town-hall meeting at the Art Trail Gallery in Florence.Christopher Fitzgerald

Always immaculately coiffed herself, Callista Gingrich double-checked her husband before his town-hall meeting at the Art Trail Gallery in Florence.Christopher Fitzgerald -

In the final days before the primary the race suddenly became very tight. Support swung behind Mr Gingrich and sent him roaring up the polls to overtake Mitt Romney.Christopher Fitzgerald

In the final days before the primary the race suddenly became very tight. Support swung behind Mr Gingrich and sent him roaring up the polls to overtake Mitt Romney.Christopher Fitzgerald -

In Columbia Ron Paul responded to the roar of approval from his enthusiastic supporters. Polls had him moving up into third place.Christopher Fitzgerald

In Columbia Ron Paul responded to the roar of approval from his enthusiastic supporters. Polls had him moving up into third place.Christopher Fitzgerald -

A final recount in Iowa showed that Rick Santorum had won the state, but support for his brand of conservatism, religion and knitware has fallen off recently.Christopher Fitzgerald

A final recount in Iowa showed that Rick Santorum had won the state, but support for his brand of conservatism, religion and knitware has fallen off recently.Christopher Fitzgerald -

a.jpg) Newt Gingrich scored a decisive victory, taking 40% of the vote, and celebrated at the Hilton Hotel in Columbia.Christopher Fitzgerald

Newt Gingrich scored a decisive victory, taking 40% of the vote, and celebrated at the Hilton Hotel in Columbia.Christopher Fitzgerald

-

The South Carolina primary

The slog begins

Jan 22nd 2012, 4:26 by J.F. | COLUMBIA, SOUTH CAROLINA

"THIS is the beginning of a long, hard slog," said Ron Paul, at his optimistically titled "Victory Party". "This is a hard fight because there's so much worth fighting for," said Mitt Romney, "and we've still got a long way to go." Indeed we do. A week ago South Carolina was going to be Mr Romney's coup-de-grace, turning Florida into an afterthought. He had won the two previous contests. Newt Gingrich, Rick Santorum and Rick Perry were squabbling over the social-conservative votes. Only Messrs Paul and Romney had the organisation and the ground game to go the distance, and Mr Paul's support had (and still seems to have) a low ceiling. But then Mr Perry dropped out, endorsing Mr Gingrich. A recount showed Mr Santorum won in Iowa. Mr Gingrich parlayed a couple of powerful debate performances into victory in South Carolina. And Mr Romney now finds himself with the wind in his face rather than at his back.

What happened in South Carolina? Erick Erickson writes that today's result was "about Republican grassroots giving the Washington Establishment the finger. The base is angry, and right now only Newt is left to fight for them." Mr Gingrich can hardly be considered a Washington outsider, having served in Congress for some 20 years, but if there is one thing the former speaker is good at, it's fighting. His debate performances this week displayed not a mastery of the issues, or any particularly novel policy proposals, but anger. His speeches have portrayed the campaign as an epic battle between an exceptional American, himself, and an un-American president. So it's hard to argue with Mr Erickson's analysis, but if you look at the exit polls, it is equally hard to be satisfied with it.

Particularly in the last week of the campaign, Mr Gingrich engaged in some expert racial dog-whistling. He called Barack Obama the "food-stamp" president (shades of Ronald Reagan's infamous "Welfare Queen") and accused him of declaring war on religion and traditional American values. He was not merely condescending to Juan Williams, the lone black moderator in the most recent debate, but effectively called him lazy at a campaign event. He then used this tussle as a campaign ad arguing that he could most effectively beat Mr Obama, who just happens to share the same skin colour as Mr Williams. These attacks seemed to go down well with primary voters, who were 99% white.

Then there is the religious angle: 64% of South Carolina's voters are white evangelicals, and 60% of those voters think it is very or somewhat important that a candidate share their religious beliefs. The Mormon Mr Romney did poorly with that group of voters, who instead gave their support to Mr Gingrich, in spite of his history of philandering. So South Carolina was always going to be unfavourable ground for the former governor; the question is what does he do now?

In the short term, he goes to Florida, where his SuperPAC has spent $7.3m on TV ads and Mr Gingrich's has spent none. Then he goes to Nevada, which is 11% Mormon, where he will do fine. He remains the likely nominee, but he will need to change tactics, and quickly too. His recent debate performances were as abysmal as Mr Gingrich's were stellar. When questioned about his wealth, he stuttered, twitched and stammered, for no good reason. He did not get rich robbing banks; he got rich by being good at his job, and if, as he said tonight, Republicans celebrate success and prosperity, he has nothing to apologise for. So he will need to confront the attacks on his business record, and tonight he made a good start, accusing Mr Gingrich of attacking free enterprise. But his air of inevitability has worn off, and his electability argument has been dented. That makes it much harder to win as everybody's second choice, and it may prove more costly in the long run than simply not winning the few delegates South Carolina offers.

(Photo credit: AFP)

The South Carolina primary

Newtmentum

Jan 21st 2012, 16:31 by J.F. | ORANGEBURG, SOUTH CAROLINA

TO THE political question of the moment several moments ago—would the interview with Marianne Gingrich harm her ex-husband Newt's prospects in the South Carolina primary—I gave a qualified maybe. My colleague's response was braver: probably not. Yet on evidence observed at Mr Gingrich's rally yesterday afternoon in Orangeburg, we were both too cautious: the interview with the ex-Mrs Gingrich may well have helped her husband.

TO THE political question of the moment several moments ago—would the interview with Marianne Gingrich harm her ex-husband Newt's prospects in the South Carolina primary—I gave a qualified maybe. My colleague's response was braver: probably not. Yet on evidence observed at Mr Gingrich's rally yesterday afternoon in Orangeburg, we were both too cautious: the interview with the ex-Mrs Gingrich may well have helped her husband.Around 700 people (that was the count from the stage, anyway) crowded into a theatre in Orangeburg yesterday to cheer Mr Gingrich, and they cared far more about his smackdown of John King than they did about what his ex-wife had to say about him. It was demagoguery, of course, but as Rod Dreher writes, it was effective demagoguery.

If Newt Gingrich wins today, as both late polls and Intrade suggest he will, it will be because he understood just how much South Carolina's Republicans were spoiling for a fight. Speaker after speaker (Mr Gingrich was running quite late; there were many warm-up acts) praised Mr Gingrich's debate performances, and said they supported him not for reasons of policy, but because they thought he could effectively tussle with Barack Obama. Mr Gingrich put "the academic left, the elite media and left-wing Democrats" on notice that his campaign was "about the end of their dominance of power" in America. He alternated between calling the president a dangerous radical and calling him incompetent; that these two qualities are incompatible troubled neither him nor the audience. Like my colleague, both he and the crowd yearn for the "great national debate" that his candidacy would occasion. Of course, my colleague thinks this debate would concern political ideas and policy proposals; Mr Gingrich thinks it will concern whether "we want to remain Americans...or do we need to become some new people." He also talked about jobs, and he introduced that discussion by reminiscing about the "very interesting dialogue" he had with Juan Williams about work, "which seemed to Juan Williams to be a strange, distant concept". It was, in short, a 45-minute-long dog-whistle symphony.

That may work in South Carolina, but what then? Well, in answer to a question about immigration, Mr Gingrich said he opposed widespread deportation, favoured allowing long-time residents with community ties to receive legal residency status, and said that undocumented immigrants brought to the United States as children ought to be able to receive citizenship for military service: a sort of DREAM Act-lite. This puts him to the left of Mitt Romney on immigration, which might come in handy in the next two primaries (Florida and Nevada, which are 22.5% and 26.5% Hispanic).

(Photo credit: AFP)

Political marriages

Marianne Gingrich shouldn't matter much

Jan 20th 2012, 20:17 by E.G. | AUSTIN

ONE of the notable things about the marriage of Barack and Michelle Obama, as depicted in Jodi Kantor's new book "The Obamas", which I reviewed for this week's paper, is that it's apparently both happy and traditional. That's not striking because of who the Obamas are, but because of the state of marriage today. In 1960, 72% of American adults were married; last year, according to the Pew Research Center, just 51% were. And the "married or single?" binary obscures the range of experiences and arrangements that are available. Still, people have not abandoned their tendency to make judgments about other people's personal relationships. As polling from Gallup shows, there are some things, like infidelity and polygamy, that most Americans consider morally unacceptable. But the traditional model of marriage—one man, one woman, legally bound, loving one other, forsaking all others, until death do us part, come what may—is apparently unrealistic or undesirable for many, and so it's getting harder to draw sweeping conclusions about people based on their personal lives.

ONE of the notable things about the marriage of Barack and Michelle Obama, as depicted in Jodi Kantor's new book "The Obamas", which I reviewed for this week's paper, is that it's apparently both happy and traditional. That's not striking because of who the Obamas are, but because of the state of marriage today. In 1960, 72% of American adults were married; last year, according to the Pew Research Center, just 51% were. And the "married or single?" binary obscures the range of experiences and arrangements that are available. Still, people have not abandoned their tendency to make judgments about other people's personal relationships. As polling from Gallup shows, there are some things, like infidelity and polygamy, that most Americans consider morally unacceptable. But the traditional model of marriage—one man, one woman, legally bound, loving one other, forsaking all others, until death do us part, come what may—is apparently unrealistic or undesirable for many, and so it's getting harder to draw sweeping conclusions about people based on their personal lives. This is the context in which we must place the question of how voters will react to Marianne Gingrich, Newt's second ex-wife, who has given a new interview claiming that her then-husband asked for an "open marriage" when he was already carrying on an affair with Callista Bisek, now his third wife. On one side there are observers who think this will be a problem and should be. "If this is true, it makes Gingrich look more French than John Kerry," writes James Taranto in the Wall Street Journal, adding that it's particularly damaging due to the contrast posed by Mitt Romney, who has been married to his "sweetheart" for 42 years, and who didn't abandon her when she was ill. The New York Times editorial board, meanwhile, scolds Mr Gingrich for hypocrisy: "It’s magnanimous of him to be willing to allow voters to decide for themselves on the importance of his moral choices, since he and his party have been so unwilling to allow the public to make its own moral choices."

But Marianne Gingrich's charges don't seem to be drawing much blood, perhaps because they are old news. Mr Gingrich's stormy marital history has been well-documented, and even the latest charge, that he wanted an open marriage, was implicit in some of Ms Gingrich's previous interviews. It's also easy to dismiss Ms Gingrich as a "disgruntled ex", as Sarah Palin did in her defence of the candidate. And the Gingrich camp may have effectively defused the problem by spinning it into a complaint about the media. "I think the destructive, vicious, negative nature of much of the news media makes it harder to govern this country, harder to attract decent people to run for public office. And I am appalled that you would begin a presidential debate on a topic like that," said Mr Gingrich at last night's debate.

Newt Gingrich

A straight fight

Jan 20th 2012, 17:57 by R.L.G. | LONDON

THE insta-wisdom on Rick Perry's departure, Sarah Palin's semi-endorsement and last night's debate are that Newt Gingrich is now probably the strongest man standing not named Ron Paul or Mitt Romney in the primaries. I still don't think Mr Romney can lose, but I must admit to myself: I would quite like to see an Obama-Gingrich election.

THE insta-wisdom on Rick Perry's departure, Sarah Palin's semi-endorsement and last night's debate are that Newt Gingrich is now probably the strongest man standing not named Ron Paul or Mitt Romney in the primaries. I still don't think Mr Romney can lose, but I must admit to myself: I would quite like to see an Obama-Gingrich election.It's not that Mr Gingrich would be the best president. But watching Mitt Romney pivot to the centre with the smoothness of a consultant flipping to his next slide, a manoeuvre we can all expect him to execute the minute he wraps up the nomination, will be depressingly predictable. The perception that he will say whatever he feels he must to become president is not founded on sand. Mr Gingrich, by contrast, can almost certainly be counted on to be the same Mr Gingrich we've seen in the primaries. Say what you like about the man, but he has ideas, says arresting things, and most of all, would make the clearest possible contrast with Barack Obama in the general election.

While some people groan at his idea for a series of "Lincoln-Douglas" debates, for example, I'd relish the chance to see Mr Gingrich and Mr Obama have long and freewheeling exchanges. "Food-stamp president" rouses South Carolinian Republicans; if Mr Romney had said it, you can imagine that he'd disown it as soon as practical. (For the same reason, he probably will not say to Mr Obama's face that he "apologised for America", a barb Mr Obama has a ready-made reply for.) But I can very easily imagine Mr Gingrich repeating the "food-stamp" line in a general-election debate with Mr Obama several feet away. This would be a natural extension of his claim that journalists asking him questions about the story of the day was "despicable". He is fearless, reckless, filterless; in any way, -less all of the things Mr Romney has too much of.

I want to see Mr Obama reply to "food-stamp president", to the idea that annoying appeals courts should be de-funded, to the Gingrich claim that he is the most radical president in history, and so much more. I dread the scripted turns the election will take if Mr Romney is the nominee. I think America could use a straight fight between two boldly different visions of America. I don't expect I'll get my wish, but a journalist can dream, anyway.

(Photo credit: AFP)

Mitt Romney's taxes

No Bain, no gains

Jan 20th 2012, 15:14 by M.S.

AS SOON as Mitt Romney acknowledged that he paid a tax rate of about 15% because almost all of his income comes from capital gains, which feels like about a million news cycles ago, a bunch of commentators rushed to declare that while Mr Romney's personification of the 1% is an unavoidable political issue, there are good arguments for charging lower tax rates on capital gains. Strangely, though, I haven't seen anyone make any of them. The closest I've seen was this widely cited post by Republican dissident David Frum. (Here's Paul Krugman citing it.) But it seems to me that while Mr Frum makes an argument for low capital-gains rates, he fails to make a good one. Here's his take:

We want capital assets put to their highest and best use. If Joe can run the company better than Jane, if Jill can make better use of the corner of Main and Elm than Jack, then we want to see ownership of that company or that corner transferred as expeditiously as possible to the higher and better user. That's why we encourage transparent and efficient markets for capital assets.

A capital gains tax is a tax on the transfer of control of assets. If that tax is set too high, it can discourage even the most glaringly urgent transfers of control. Under Joe's management, the value of the company may rise 30%. But if the capital gains rate is set at 50%, then the transaction from Jane to Joe will not occur—and everybody will be worse off.

The first part of this parable confuses ownership with management. As John Kay recently pointed out while arguing against the current usage of the term "capitalism", few significant modern enterprises are managed by their owners. For the overwhelming majority of cases in the modern business world, if Joe can run the company better than Jane, then what we want to see is for the board of directors to fire chief executive Jane and hire Joe to replace her. This has little to do with capital gains. People who report capital gains due to ownership of a company are generally not active players in the company's activities; they're stockholders. And that, obviously, is what Mr Romney made his money from last year. He's no longer running Bain Capital, taking over companies and trying to rejigger their assets or run them better. He's a retired executive with an estimated $200m-plus in assets that are producing revenue for him in the way that assets have always produced revenues for wealthy rentiers.

In many cases, efficient deployment of capital does depend on companies acquiring assets they can put to use better than another owner could, as with a merger or acquisition. But capital-gains taxes usually play a minor role here, because expected appreciation of the shares or assets of the target company after it is acquired is not usually a major reason for the deal to go through, except in private-equity takeovers. When Daimler acquires a majority stake in Chrysler, they're mostly thinking about synergies and market share, not potential gains from selling off Chrysler stock in the future if it appreciates, though that consideration isn't entirely absent.

What low capital-gains tax rates mostly do is to encourage people to save their money by investing in assets, rather than saving it in vehicles that pay interest or dividends, or spending it on consumption goods.

Now, one may say, that's good. We want people to save and invest. True enough (though why capital gains are more virtuous than earning interest or dividends is an open question). But we also want people to work hard to earn money and create value. If we don't tax capital gains, that means we need to get the money to fund the government by taxing something else, probably income. And taxing income means there's less incentive to work hard. Mr Frum is weak on this point, too:

The underlying asset will have taxes assessed against it: corporate income taxes if it is a company, property taxes if it is a piece of land. Those taxes are paid the day before the transfer of ownership, and they continue to be paid the day after. A transfer of ownership transfers the obligation to pay the tax. But the amount of tax collection in the economy is not diminished by the transfer, and it's difficult to justify why the occasion of transfer should trigger yet more taxes.

Sure, the corporation still has to pay taxes on its income. But if lower taxes are assessed on the transfer, then something else is going to have to be taxed more highly in order for the government to be able to pay its bills. The question with taxation is never whether or not to tax; it's whether this type of tax is a better or worse way to raise revenue than some other kind of tax. Mr Frum never makes an argument that capital-gains taxes are worse for the economy than income taxes, or sales taxes. And Greg Anrig adds another point: the capital-gains tax introduces tremendous complexity into the tax code, which creates inefficiency and distortions of its own.

But here's the main point. As Mr Krugman notes, capital-gains taxes have only been 15% since 2003. From 1987-1996, they stayed around 28%. We now have capital-gains taxes that are just over half as high as in the old dystopian socialist days of Ronald Reagan's economy.

If higher capital-gains taxes led to lazy management and widespread misapplication of capital, you would have expected American businesses to have become vastly better managed and more efficient starting in 2003. If this was supposed to lead to higher growth, you would have expected GDP growth in America to be significantly greater from 2003 on than it was in the late 1980s and 90s.

Does anyone seriously think this has happened? It just doesn't sound like a good description of the history of the US economy over the past 20-odd years. What we have seen, however, were two tremendous asset bubbles, the first concentrated on the stockmarket, the second on housing, as people's money was used in ways that let them take advantage of low capital-gains taxes. As Mr Anrig writes:

Advocates of the capital gains tax break have claimed for decades that the exclusion benefits the economy and all workers by encouraging higher levels of investment and savings, which in turn promote growth and prosperity. But researchers have never been able to demonstrate that such connections actually exist. Capital gains tax rates have gone up and down over the years with little apparent relation to economic performance, aside from fleeting effects on realization of capital gains when rates change.

I think you can probably make some good arguments for taxing savings at a lower rate than income. You can argue, for example, that high capital-gains taxes don't actually produce that much more revenue, because they just lead people to hold assets for longer. Or you can point out that capital-gains taxes need to be lower than income taxes in order to compensate for inflation, which makes assets appear to have appreciated even though they really haven't. But Mr Frum doesn't make those arguments. In fact, nobody's making any arguments on that side that are very convincing. A number of people are nodding to the claim that such arguments exist, but nobody seems to be producing them.

The Republican nomination

Live-blogging the Republican debate

Jan 20th 2012, 0:56 by The Economist online

(Photo credit: AFP)

Rick Perry

So long, pardner

Jan 19th 2012, 21:22 by E.G. | AUSTIN

AFTER observing Rick Perry at close range for the last few years, I had thought that he would be a strong candidate for the Republican presidential nomination. He's a strong business conservative who has governed a state with a cracking economy, and although he has all the right-wing rhetoric down, his record has been more moderate than his public profile suggests. He is a good retail politician, and likeable. I never thought he was dumb (and still don't); lazy, perhaps, but as a small-government type, that doesn't really bother me.

AFTER observing Rick Perry at close range for the last few years, I had thought that he would be a strong candidate for the Republican presidential nomination. He's a strong business conservative who has governed a state with a cracking economy, and although he has all the right-wing rhetoric down, his record has been more moderate than his public profile suggests. He is a good retail politician, and likeable. I never thought he was dumb (and still don't); lazy, perhaps, but as a small-government type, that doesn't really bother me.On the one hand, Mr Perry might seem like just another campaign casualty; national politics is unpredictable, and this year has been especially capricious. America is occasionally criticised for its long election cycles, and it certainly creates some problems, but one of the virtues of this system is that it lets voters put the candidates through their paces. Campaigning is not the same as governing, of course, but it does require endurance, discipline, and commitment, all of which are relevant traits in a would-be president. When Barack Obama joined the presidential race in 2007, there were millions of sceptics who thought he was too young and inexperienced; over the course of a long primary and fierce general election, he proved that he was more than just a pretty face. In this cycle, we've seen Rick Santorum and Newt Gingrich—neither of whom was considered a serious contender when they entered—fight their way into the top tier.

And sometimes candidates can't hack it. Mr Perry is actually the third candidate to enter the race with great expectations only to drastically underperform and drop out. The other two are Jon Huntsman and Tim Pawlenty. The fact that all three are former or current governors is curious. Perhaps the mood among Republican voters is not as anti-Washington as they say it is. More importantly, you don't know how somebody is going to perform on the national stage until they're on the national stage. (The other governor in the race, Mitt Romney, is likely to be the nominee, but he's been a national figure for more than five years.) When Mr Huntsman left, I said that despite his credentials, he just didn't have the "magic touch" for national politics. That could be part of the issue for Mr Perry too.

However, that analysis is ultimately too generous to Mr Perry. He lost this race fair and square. The voters gave him a serious look—at one point he was polling in the low 30s, which is about where Mr Romney is now—and they weren't impressed by what they saw. Most of the blame for that must go to the candidate. He did get hammered from all directions, in some cases a little unfairly. The attacks on the "Texas miracle", for example, were motivated as much by a desire to tear down Mr Perry as to have a substantive discussion about job creation, a rather important topic. But it was Mr Perry's job to counter those attacks, and he bungled it. His prescription for America's domestic ills seemed to involve fossil fuels, a flat tax, and little else. His views on foreign policy were at times both glib and belligerent; when asked how he would deal with Turkey, an American ally, he implied that it was run by Islamic terrorists. He also bungled his debate performances, which were at some points so rough that even liberal commentators had moments of sympathy.

But the debates do not test character in the way a fading campaign does, and here too Mr Perry disappointed. As his candidacy foundered, he indulged in some unpleasant pandering politics in an apparent bid to win over the social conservatives who had assessed (correctly) that he wasn't much of a holy warrior, even if he did host the occasional prayer rally. Having previously taken a sanguine view of gay marriage, he decided to target gays in the run-up to the Iowa caucuses. As the South Carolina primary approached, he ranted about "Obama's war on religion."

None of it helped. And so perhaps the greatest takeaway from Mr Perry's campaign is that it's a bad idea for candidates to run on anything other than their beliefs. The Texas governor did stick to some of his talking points, about the importance of fiscal discipline and the 10th amendment, but was uninformed about many issues, and pandered on others. It was enough to alienate moderates, not enough to convince the target audience, and it took the focus off his areas of strength. It may be that it's possible to win an election without having an extremely clear message—ask Mr Romney. But more often than not presidential campaigns don't pan out, and in the cases when they don't, it's the candidates who have a clear cause who retain their role as advocates—ask Ron Paul. "I have always believed the mission is greater than the man," said Mr Perry earlier today, but after making such a hard play for the social conservatives, it's not clear what the mission was. He would be in a stronger position now if he had stuck to his core interests and arguments.

(Photo credit: AFP)

The chaotic caucuses

In defence of Iowa

Jan 19th 2012, 19:42 by E.M. | WASHINGTON, DC

THE news that over 100 precincts in Iowa somehow botched their reporting of the results in the Republican caucuses earlier this month, and that as a result, it is Rick Santorum rather than Mitt Romney who officially won, has reinvigorated America’s ravening mob of Iowa-bashers. How can we entrust such vast influence over the presidential race to a bunch of bumpkins so witless that they can’t even count themselves, the basic argument runs. In addition to being out of step with the country by virtue of their whiteness, their elderliness and their godliness, they also turn out to be utterly incompetent. As often as not, they plump for someone (like Rick Santorum) who stands no chance of winning the nomination, let alone the general election. Why on earth do we pay them any attention?

THE news that over 100 precincts in Iowa somehow botched their reporting of the results in the Republican caucuses earlier this month, and that as a result, it is Rick Santorum rather than Mitt Romney who officially won, has reinvigorated America’s ravening mob of Iowa-bashers. How can we entrust such vast influence over the presidential race to a bunch of bumpkins so witless that they can’t even count themselves, the basic argument runs. In addition to being out of step with the country by virtue of their whiteness, their elderliness and their godliness, they also turn out to be utterly incompetent. As often as not, they plump for someone (like Rick Santorum) who stands no chance of winning the nomination, let alone the general election. Why on earth do we pay them any attention?As someone who has been forced to pay Iowans a lot of attention over the past few months, I have to say I’m not surprised that they made a pig’s breakfast of the caucus results. The two caucuses I attended (they all happen at the same time, but they drag on a bit, so it is possible to rush between two nearby locations) were both amateurish affairs. At the first location, in the small town of Treynor, there was much farcical banging of gavels and seconding of motions to get the acting presiding officer and the acting secretary elevated to the rank of presiding officer and secretary. That was followed by more banging and seconding as the presiding officer temporarily relinquished his newly acquired powers to the newly installed secretary so that he could speak, as an ordinary citizen, on behalf of Mr Santorum. At least Mr Santorum had someone to speak for him. There was an awkward echo of "Ferris Bueller’s Day Off" as the presiding officer (back in command after more banging and seconding) asked for volunteers to speak on behalf of Michele Bachmann, Newt Gingrich, Jon Huntsman and Rick Perry: “Anyone? Anyone?” Finally a shy farmer in overalls and a baseball cap lumbered forward to rally votes for Mrs Bachmann with the stirring phrase, “I just kinda like her.”

At the second caucus, in the suburbs of Council Bluffs, Iowa’s seventh-biggest city, the scene was equally shambolic. To tally the votes, the harried-looking secretary separated the ballots into piles for each candidate, hastily counted them and then jotted down the totals on a scrap of paper. He called in the results on his cellphone, visibly struggling to hear over the happy chatting of bystanders. There did not appear to be much oversight, either from the presiding officer or from the representatives of the candidates—and who knows what happened at the other end of the phone line.

Having said all that, the process was perfect as far as I was concerned. There was none of the razzle-dazzle of the modern campaign—just concerned locals getting together with their neighbours for a chat about the candidates, with all the folksy ineptitude that entails. Jefferson would have been proud.

And that authenticity, ultimately, is why Iowa’s exalted position seems worth preserving to me. In a bigger state, or a more urban one, or a less homogeneous one, or one with a primary rather than a caucus, the parish-fete-committee-meeting atmosphere would be swept away. Instead of having the recused presiding officer speak for Mr Santorum (and swung it his way in Treynor, at least), it would be entirely up to the pundits, the attack ads and the campaign mailers to set the tone. Iowa is unlike the rest of America, in that it gets to engage with the presidential campaign at a meaningful, personal, everyday level. If only the rest of the country could be more like that.

(Photo credit: AFP)

The Republican debate

Programming note

Jan 19th 2012, 18:05 by R.M. | WASHINGTON, DC

THE candidates gather in South Carolina tonight for what is sure to be the best debate of Rick Perry's campaign. And this meal comes with a digestif: Nightline's interview with Marianne Gingrich. We'll be live-blogging the debate, which starts at 8pm ET on CNN.

Iowa, Rick Perry and Marianne Gingrich

Reversal of fortune

Jan 19th 2012, 16:59 by J.F. | GREENVILLE, SOUTH CAROLINA

SOUTH CAROLINA was always going to be hard going for Mitt Romney. He is a northerner, a Mormon and previously held socially liberal views, all of which count as hurdles for South Carolina's evangelical, socially conservative voters. But he came in with the wind at his back: he was the first Republican to win both the Iowa caucuses and the New Hampshire primary. Except, it appears, he wasn't: with data from eight precincts missing and unlikely to be recovered or certified, Rick Santorum finished 34 votes ahead. The executive director of Iowa's Republican Party called it "a split decision". How much will this matter? Hard to say. Mr Romney already received the benefits of victory: media attention, a hopeful narrative, fund-raising. No delegates were officially at stake, and by the time Iowa awards its delegates in June the election will almost certainly be in the bag.

SOUTH CAROLINA was always going to be hard going for Mitt Romney. He is a northerner, a Mormon and previously held socially liberal views, all of which count as hurdles for South Carolina's evangelical, socially conservative voters. But he came in with the wind at his back: he was the first Republican to win both the Iowa caucuses and the New Hampshire primary. Except, it appears, he wasn't: with data from eight precincts missing and unlikely to be recovered or certified, Rick Santorum finished 34 votes ahead. The executive director of Iowa's Republican Party called it "a split decision". How much will this matter? Hard to say. Mr Romney already received the benefits of victory: media attention, a hopeful narrative, fund-raising. No delegates were officially at stake, and by the time Iowa awards its delegates in June the election will almost certainly be in the bag.Of more import will likely be Rick Perry's departure. Dave Weigel writes that this will help Newt Gingrich, and not just because Mr Perry has formally endorsed Mr Gingrich, either. Often Mr Gingrich and Rick Santorum are seen as drawing from similar voter banks, and to a certain extent they are. But Mr Santorum's mien and his version of populism are rather more serious than Messrs Gingrich's and Perry's. He talks about important, unsexy things like manufacturing and rural poverty, and when he discusses moral issues, he comes across as firm and earnest in his convictions, batty and repugnant though they may be. Mr Gingrich, by contrast, is pure id, like Mr Perry. Not for nothing did Doonesbury depict him as a lit bomb. Another way of saying this is that Mr Santorum is a more serious candidate, politician and person than either Mr Gingrich or Mr Perry, and in this primary that seems to count as a handicap.

And Mr Gingrich could use the help today. ABC News plans to air an interview with Marianne, the second of Mr Gingrich's ex-wives, tonight, in which she says Mr Gingrich wanted to remain married to her while carrying on an affair with Callista Bisek, now the third Mrs Gingrich. If that is all the interview reveals, it is old news: the former Mrs Gingrich gave an interview to Esquire in 2010 that covered much the same ground. Besides, we knew Mr Gingrich had a messy marital history already. We even know the pattern: twice he had marriage-ending affairs; twice he married his former mistress. And an ex-wife speaking poorly of a husband who cheated on her and left her for a younger woman does not exactly strike me as unusual. But if she has more to say than this? Of course, there is a difference between reading an article about Mrs Gingrich and watching her tell her story, in her own words, on network television, two days before a primary election. The conventional wisdom is that Mr Gingrich is already inoculated against the effects of damaging revelations about his personal life. He had better hope that wisdom holds.

(Photo credit: AFP)

The Republican nomination

Red-meat delivery

Jan 19th 2012, 14:48 by J.F. | GREENVILLE, SOUTH CAROLINA

A MAN with my cholesterol levels has no business being fed as much pure red meat as was offered at last night's campaign event. Devoted to abortion and held by Personhood USA, about whom we've written before, the forum drew Rick Perry, Newt Gingrich, Rick Santorum and Ron Paul to a rather dreary Hilton on the outskirts of Greenville (Mr Paul appeared via satellite from Washington, DC, having briefly stepped off the campaign trail to vote against a debt-ceiling increase) to answer a penetrating set of questions. Is life important? It is. Is there anything more important than life? There is not. Is abortion wrong? It is. When does life begin? At the moment of conception. So far, so unsurprising. The gems were further down in the questioning line.

Rick Perry went first. He was loose, funny and relaxed as only a man about to drop out of the presidential race could be. He genially floundered his way through some substantive questions about constitutional law, and declared his opposition to abortion so strong that he would bring government to a halt rather than sign any bill that included abortion-related funding. He sparked to life only when he started talking about Barack Obama ("this administration is at war with religion") and Mitt Romney. The latter's relatively recent discovery that he was in fact opposed to abortion rights was, Mr Perry charged, "a decision [he] made for political convenience, not an issue of the heart."

Rick Perry went first. He was loose, funny and relaxed as only a man about to drop out of the presidential race could be. He genially floundered his way through some substantive questions about constitutional law, and declared his opposition to abortion so strong that he would bring government to a halt rather than sign any bill that included abortion-related funding. He sparked to life only when he started talking about Barack Obama ("this administration is at war with religion") and Mitt Romney. The latter's relatively recent discovery that he was in fact opposed to abortion rights was, Mr Perry charged, "a decision [he] made for political convenience, not an issue of the heart."Mr Perry's problem has always been the culture-warrior's problem: only opposition moves him. He can rile a crowd as well as—and in the same way as—Pat Buchanan. Let a thousand pitchforks gleam! But then what? Ask Ron Paul why he wants to be president and he’ll bang on about fractional banking and the Fed and sound money and raw milk until he dislocates his shoulders from excessive twitching. Ask Newt the same thing and he’ll tell you why we’re at the most perilous point in human history and we need to fundamentally transform the way we breathe air and eat food and he’s the only American politician to ever truly understand human civilisation and by the way can he tell you about his plan to send poor children to mine tungsten on the moons of Neptune. Ask Mr Perry why he wanted to be president and all he could tell you is how awful the other guys are. That was necessary but insufficient. The crowd knew it, and apparently he does too now.

Still, he set in motion a contest—which candidate is most vehemently opposed to abortion rights, and who will do the most to curtail them—that the next three contestants took up with zeal. Newt Gingrich came out in full snarl, decrying "a secular judiciary that seeks to impose elite values on a country that deeply dislikes it." He offered a novel solution to this problem—one that went beyond his call for "aggressive, articulate leadership", a self-advertisement if ever there was one. If a court makes "a fundamentally wrong decision", the president can ignore it and Congress can abolish it. Mr Gingrich brushed off a panelist's suggestion this simply switched "tyranny by five justices for tyranny from one executive." If Congress sides with the Supreme Court against the president, it can vote to defund the presidency. If Congress supports the president, it can abolish the judiciary. "This is not something you would do capriciously," Mr Gingrich cautioned, in perhaps his first-ever understatement. "But I fully expect that as president there will be several occasions when we would collide." Phew! A Gingrich administration would see frequent rather than perpetual inter-governmental chaos. I'm relieved.

Rick Santorum also promised to "fight the courts". The president and every member of Congress takes an oath to uphold the constitution; "we have just as much say as they do." One wonders what their response would be if Mr Obama decided he was going to unilaterally ignore the Citizens United decision. Or imagine he had a Democratic majority in Congress and they passed legislation outlawing corporate political contributions. That certainly is in line with the Gingrich-Santorum view of a weak and dismissible judiciary. Still, Mr Santorum's main target was not law but science. "Science", he declared in answer to a question about experimental cloning, "is not an ethics- or moral-free zone. It is something society has every right—in fact, an obligation—to curb."

The crowd loved these attacks (though the night's biggest cheers went to Ron Paul's giant televised head), and there's nothing wrong with a little pre-primary pander. But what would America's schools look like under a president contemptuous of science and education? And if America's political system is fractious and prone to gridlock now, what will it look like when the president starts ignoring and undermining the courts? The best one can say about such full-on attacks on law and science is to hope the candidates are making them in bad faith.

(Photo credit: Reuters)

INTERACTIVE: Explore our map and guide to the race for the Republican candidacy

Mormonism

Just as incredible as Christianity

Jan 18th 2012, 21:45 by R.M. | WASHINGTON, DC

MY FAVOURITE sentence from last week's leader on Mitt Romney concerns the difficulty presented by his religion, Mormonism, which one in three Americans do not consider to be a branch of Christianity. As we say in the piece, there isn't much the candidate can do about this. "He could explain the Mormons’ extraordinary missionary work, but he can hardly risk saying that it is not really any more incredible that God communicated His plans to man in upstate New York in 1820 than He did in Palestine in 0AD."

I was reminded of that sentence when reading Sam Harris's advice for Mr Romney. Mr Harris says that in order to appease Republicans, 60% of whom believe God created humans 10,000 years ago, he ought to say the following:

I believe what you believe. Your God is my God. I believe that Jesus Christ was the Messiah and the Son of God, crucified for our sins, and resurrected for our salvation. And I believe that He will return to earth to judge the living and the dead.

But my Church offers a further revelation: We believe that when Jesus Christ returns to earth, He will return, not to Jerusalem, or to Baghdad, but to this great nation—and His first stop will be Jackson County, Missouri. The LDS Church teaches that the Garden of Eden itself was in Missouri! Friends, it is a marvelous vision. Some Christians profess not to like this teaching. But I ask you, where would you rather the Garden of Eden be, in the great state of Missouri or in some hellhole in the Middle East?

Mr Harris is being silly, of course, though he is accurately portraying Mormon beliefs. Prior to this bit, he has Mr Romney explaining to Republicans the teachings of his church, how they were derived "directly from the prophetic experience of its founder, Joseph Smith Jr., who by the aid of sacred seer stones, the Urim and Thummim, was able to decipher the final revelations of God which were written in reformed Egyptian upon a set golden plates revealed to him by the angel Moroni." To most non-Mormons, such events sound wholly unbelievable, just as few believe the Garden of Eden was actually located in Jackson County. It is odd, though, that many who find such stories bizarre, have little trouble believing in older tales involving magical fruit and talking serpents.

I was recently in Salt Lake City and walked around the pristine headquarters of the Mormon church. The iconography is a bit jarring at first: sculptures and paintings of men in relatively modern clothes being visited by angels. But if you put some robes on these fellows, and perhaps gave them beards, they wouldn't seem out of place in a Christian church. Which isn't to say that the doctrinal divide between Christianity and Mormonism isn't real. The point, rather, is that to perceive ridiculousness in any of these religions is to perceive ridiculousness in them all. There is enough magic and mythology in most of our pious beliefs that any believer must feel reluctant to throw stones.

Like most religions, Mormonism has other issues that invite derision, such as its history of polygamy and institutional racism. But its greatest vulnerability may simply be that it is relatively young, so has not yet become established in America's religious pantheon, and that it came of being at a time when good records were kept, which means we are better able to scrutinise its origins. Nevertheless, the divinely-inspired events of two centuries ago are hardly less believable (or unbelievable) than those that preceded them by some two millennia.

The good news for Mitt Romney is that none of this will matter if he wins the Republican nomination. Such is the level of disdain for the current president among religious-minded voters that they will eventually rally around the Republican nominee, even if he turns out to be a "non-Christian". In a Pew poll from December, 91% of white evangelical Republican voters said they would support Mr Romney, and 79% said they would support him "strongly". For them, it's hardly a choice: elect the guy who wants to be in their Christian club, or re-elect the man who some of them have called the anti-Christ.

Keystone XL

Still in the pipeline

Jan 18th 2012, 21:20 by S.W.

BARACK OBAMA'S decision last year to put off a judgment on a proposed oil pipeline between Canada and Texas until after this year's presidential election swept a tricky problem under the carpet. Supporters pointed out that Keystone XL, a pipeline that would carry oil from Alberta's tar sands, as well as some from America's Bakken shale fields, would bring not just added energy security but jobs aplenty. Environmentalists would have none of these supposed advantages, decrying emissions-heavy oil from tar sands and claiming that in the event of a leak, the pipeline threatened a vulnerable aquifer on its route through Nebraska.

BARACK OBAMA'S decision last year to put off a judgment on a proposed oil pipeline between Canada and Texas until after this year's presidential election swept a tricky problem under the carpet. Supporters pointed out that Keystone XL, a pipeline that would carry oil from Alberta's tar sands, as well as some from America's Bakken shale fields, would bring not just added energy security but jobs aplenty. Environmentalists would have none of these supposed advantages, decrying emissions-heavy oil from tar sands and claiming that in the event of a leak, the pipeline threatened a vulnerable aquifer on its route through Nebraska.So the administration's announcement that it will now slap a big "rejected" stamp on the application from TransCanada, the Canadian company that wants to build and operate Keystone XL, seems to come down firmly on the side of the greens. But Mr Obama is still treading a fine line between the two sides. Thanks to resistance to the pipeline from Republican politicians in Nebraska last year, TransCanada had already offered to reroute it to avoid the Sandhills, a part of the state where the massive Ogallala aquifer rises almost to the surface. The ostensible reason for last year's delay was the need to study new routes (the unspoken ones being to duck a tough decision and placate the green lobby). The assumption was that the pipeline would eventually be approved in some form, but not at such an awkward time.

Republicans in Congress, however, tried to force the president's hand by inserting into an important spending bill a clause obliging him to rule one way or another by the end of February. The administration now claims, insouciantly, that it had to rule against the pipeline because the Republicans had denied it the chance to consider all the risks properly. In fact, little has changed. TransCanada can submit a new application for a similar pipeline following a new route, giving Mr Obama the respite he wanted while allowing him to bask in green adulation for now. The Republicans, for their part, can now make slightly stronger attack ads about Mr Obama's foot-dragging in the run-up to the election in November.

Meanwhile, the delays have strengthened Canadian resolve to find new ways of getting tar-sands oil to global markets. This might mean expanding an existing pipeline and building a new one to Canada's west coast for shipment to Asia's oil-thirsty markets. The western province of British Columbia, however, has feisty environmentalists of its own who might yet have a say.

The Chamber of Commerce is gnashing its teeth about the decision, but there are some American businesses who will rejoice at the new delay. The final section of the pipeline would have taken oil from Cushing, Oklahoma, to the Gulf coast, helping to alleviate a persistent price differential between Brent crude, the global benchmark oil, and West Texas Intermediate. Cushing, where most American oil is delivered is landlocked. There is not nearly enough pipeline capacity to the Gulf where global markets set prices. Unfortunately for American drivers, petrol (gasoline) is globally traded. The upshot is that local refiners can buy cheap Cushing crude and sell petrol at dearer global prices. So at least Mr Obama is keeping one lot of businessmen happy.

Newt Gingrich

Newt and the "food-stamp president"

Jan 18th 2012, 14:02 by W.W. | IOWA CITY

THE AUDIENCE of Monday night's Republican debate in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina reached its climax of enthusiasm during Newt Gingrich's exchange with Juan Williams, who asked Mr Gingrich if he could perhaps see how certain comments he has made in the past might give special offence to black Americans. Mr Gingrich is now using highlights from the confrontation with Mr Williams in order to make the case that "Only Newt Gingrich can beat Barack Obama" in a TV spot airing in South Carolina. In case you missed it, or can bear to refresh your memory, here is the exchange in full:

When Mr Gingrich replied to Mr Williams that he cannot see why some might take umbrage at his comments that black Americans "should demand jobs, not food stamps" and that poor kids tend to lack a strong work ethic, I don't think it's quite right to say he was "playing dumb". On the contrary, Mr Gingrich acts as though he is so morally evolved, so essentially oriented toward truth—as though he surveys the world from such an Olympian height, through such crystalline air—that he is unable even to imagine how his use of venerable racist tropes could be sensibly seen to serve a purpose other than transmission of the plain truth. This haughty pose flatters the bigots, who Mr Gingrich knows full well are roused by talk of food stamps and an underdeveloped taste for honest labour, reframing their hoary prejudice as gallant unflinching fidelity to facts.

In response to Mr Williams' quixotic second attempt to coax the former speaker of the House into acknowledging that insistently calling Barack Obama "the food-stamp president" smacks of racial politics, Mr Gingrich rejoined: "First of all, Juan, more people have been put on food stamps by Barack Obama than any president in history." This incredibly misleading claim sent the crowd into an ecstasy of delight. "I know among the politically correct you're not supposed to use facts that are uncomfortable", Mr Gingrich added to the warm applause of those in attendance brave enough to face the truth.

Of course, Barack Obama has put no one on food stamps. Population growth together with the most severe recession since the advent of the modern American welfare state, which was in full swing when Mr Obama came into office, conspired to make a record number eligible for government food assistance. The Obama administration has moved to expand eligibility for the SNAP programme, but the initiative has not come to fruition. That there is a safety net, and that it succeeds in keeping millions of Americans from the misery and humiliation of hunger, may be an uncomfortable fact for Mr Gingrich, but not for Mr Obama or for any of those among us who do not lament this humane achievement.

A thought experiment: On Twin Earth, does anyone call President John McCain the "food-stamp president"? Is it "politically incorrect" there to call him that? Or is it just so tactically weird to pin that label on a white Republican who inherited a huge recession that the idea simply never occurred to anyone? If, back in our world, it's not "politically correct" and not tactically weird to pin that label on a black Democrat who inherited a huge recession, then why not?

College tuition

What high school is worth on the free market

Jan 17th 2012, 14:59 by M.S.

KEVIN DRUM worries that the high cost of college tuition is driven by the very large value of lifetime earnings gains derived from a college degree. He agrees with Kevin Carey that federal tuition subsidies and easy loans are part of what's driving up the price of a college education, but he thinks the real story is "more depressing": As long as we keep giving people whatever student loans they need to attend college, and absent any regulatory price controls, colleges will hike tuition to the very limit of what it's worth in higher wages.

[I]t's not just that universities are steadily making up for distortions caused by federal aid. The fact is that we've never been in a situation where universities were charging a market price in the first place. After all, if the lifetime wage premium for a college grad is a million dollars over 40 years, then how much is four years of college worth today? Answer: about $300,000 or so. That's $75,000 per year...

For many decades, universities acted as though they had a public, charitable mission. That was especially true for state universities, but it was true for most private universities too. That's largely changed. In the public sphere, taxpayers have noticed that (a) it's mostly well-off kids who go to college these days, not children of the poor bettering themselves, and (b) this education is worth a helluva lot of money. So why should they be asked to subsidize a route to higher earnings for kids who, for the most part, already have a lot of advantages? The cost of college loans seems more and more like a simple financial transaction to them, not a crushing burden being placed on struggling youngsters.

In the private sector, I'd guess that universities are simply coming to grips with the fact that they can charge a lot more than they ever imagined. They're testing the boundaries of their market price, and they haven't found it yet. Until they do, tuition costs will continue to skyrocket.

Mr Drum doesn't put this forward as a definitive figure. But the basic point seems valid, and I think there's one more consideration we need to mention: This seems like a particularly clear case where the market value of a good is much lower than its social value. One way to express this point is that the social value of each student's college degree is $1m. That's the earnings they'll add to the entire economy if they get a college degree. But without subsidies, the market value will be much lower, because most people can't afford to spend $300,000 on a college education, and will be reluctant to borrow that much even if banks are willing to loan it to them. Because the market value will be lower than the social value, the goods will be under-provided. Scrap government subsidies, and you may keep college tuitions down. But you'll be accomplishing that by ensuring that a whole lot of potential students decide not to go to college, which will ultimately mean poorer Americans and lower GDP.

Another way to think about this would be to ask what high-school tuition would cost if we didn't guarantee a free high-school education to every child, and instead funded it the way we do college education, by loaning people the money to pay for it. Assume the social value of a high-school degree is just the difference in lifetime earnings between a high-school graduate and a drop-out. According to Princeton's Cecilia Rouse, that was about $260,000 as of 2005. (In fact this greatly understates the earnings difference: it's just the difference between lifetime earnings for drop-outs and those with only a high-school degree. Since you need to finish high school in order to go on to college, we should really be factoring in some part of the eventual earnings difference for those with college degrees or higher. But I don't have those stats and it would be hard to decide what fraction of those earnings to include, so let's leave it at $260,000 and recognise that we're low-balling it.)

So how much is $260,000 in lifetime earnings worth today? I'm not sure how Mr Drum got his $300,000 figure, but I assume it's a future value calculation of what sum you'd have to invest to get $1m at some reasonable rate of return over 40 years. Which means he's estimating a real return of about 3% per year. Assuming a high-school grad or drop-out works perhaps five more years than a college grad over the course of their lifetime, what would you have to invest to end up with about $260,000 after 45 years at a return of 3% per year? If I'm doing my math right (1/ert * 260,000), it's about $67,500. So we're talking four years of high-school tuition at almost $17,000 a year. And, again, this is probably significantly low-balling the real value of that degree.

How many American parents can pay $17,000 a year per kid for their kids to go to high school? Say this math overestimates the present value of the degree, and the actual figure is only $10,000. How many parents could afford to pay that? How many can borrow that much on the private market? How many would be willing to, if they could? What percentage of American kids would graduate from high school if they or their parents had to pay the full future value of their education up front? Currently 70% of Americans graduate from high school; imagine that percentage dropped to even 50%. And here's the money question: How much poorer would America be, how much lower would our GDP be, if only 50% of Americans graduated from high school? I think this is the way we need to think about the value of government subsidies for, and/or cost controls on, and/or provision of low-cost Skype-enhanced alternatives to universal college education.

The Republican nomination

Live-blogging the Republican debate

Jan 17th 2012, 1:58 by The Economist online

(Photo credit: AFP)

Jon Huntsman

Not just too moderate

Jan 16th 2012, 21:26 by E.G. | AUSTIN

MOST observers will be stoical about the fact that Jon Huntsman has left the presidential race, as he never seemed to have much chance at winning, but many will also be a bit sad. Mr Huntsman is a thoughtful politician and a credible person, which would be faint praise if there were more of them around.

MOST observers will be stoical about the fact that Jon Huntsman has left the presidential race, as he never seemed to have much chance at winning, but many will also be a bit sad. Mr Huntsman is a thoughtful politician and a credible person, which would be faint praise if there were more of them around.He might be back, so let's skip the eulogies and go straight to the analysis. There are several ways to understand the untimely end of the Huntsman campaign. One is that despite the good press, and regardless of his policies, he simply wasn't a good candidate. "He just wasn't any good at projecting an intriguing image," as Kevin Drum puts it. That may be a factor in any capsized candidacy. There are some people who seem to have a magic touch for national politics, and others who don't. It's a capricious quality that doesn't necessarily track with someone's charisma, intelligence or experience.

Another popular explanation of Mr Huntsman's failure to catch fire is that he was too moderate to win the Republican primary at a moment when the conservatives are so full of beans. "The early wisdom was actually right," writes David Weigel. "Divided as they are, ready as they are to let Mitt Romney win the nomination anyway, Republicans in 2012 had no interest in a compromise candidate who could speak Democratic parseltongue."

This is an appealing argument because it partly corresponds to the observable world, and I think it's largely correct. But it does gloss over the fact that a moderate is probably going to win the Republican presidential nomination. It may be that Mr Romney is not as close to the political centre as Mr Huntsman, having tacked to the right in both of his presidential campaigns, but there are some glaring blue blots on the Romney record, and he's clearly considered a moderate relative to the rest of the Republican field.

A slight variation is that Mr Huntsman's problem is not just that he was too moderate, but that he was too similar to Mr Romney, at least according to the rough typecasting of a presidential primary. The two were largely campaigning for the same voters—moderate Republicans and independents, the business conservative crowd, pragmatic people, people who aren't frightened about Mormons. Now Mr Huntsman has already endorsed Mr Romney, skipping the usual mini-drama of pretending to mull his endorsement (and despite the fact that he often attacked Mr Romney on the trail). Most of Mr Huntsman's voters probably will go to Mr Romney, if not to Barack Obama or Ron Paul. It might be that Mr Huntsman would have had more success, if not for the fact that Mr Romney had a head start of four years and millions of dollars. But now it's Mr Huntsman who has the head start for next time.

(Photo credit: AFP)

The Republican debate, sans Jon Huntsman

Programming note

Jan 16th 2012, 16:20 by R.M. | WASHINGTON

DURING our live-blog of the New Hampshire primary results, none of us were sold on Jon Huntsman's claim to have won a "ticket to ride" to South Carolina. It now seems even he wasn't convinced. Mr Huntsman has dropped out of the race and endorsed Mitt Romney (whom he previously pilloried in online attacks). More pertinent to our own tasks, the loss of Mr Huntsman means one less sensible (albeit dull and dispassionate) voice on tonight's debate stage. I'll leave you to debate how many sensible voices are now left. The candidates begin sparring at 9pm ET on Fox News. Our live-blog will begin shortly before then.

Washington and its statues

Time for a memorialtorium

Jan 16th 2012, 14:27 by M.S.

CHARLES DODGSON, otherwise known as Lewis Carroll, didn't much like travel, which makes his notes on one trip he did take, to Berlin in 1867, all the more entertaining. In particular there's a passage about what he calls the chief principle of Berlin architecture that has always stuck in my memory:

CHARLES DODGSON, otherwise known as Lewis Carroll, didn't much like travel, which makes his notes on one trip he did take, to Berlin in 1867, all the more entertaining. In particular there's a passage about what he calls the chief principle of Berlin architecture that has always stuck in my memory:Wherever there is room on the ground, put either a circular group of busts on pedestals, in consultation, all looking inwards—or else the colossal figure of a man killing, about to kill, or having killed (the present tense is preferred) a beast; the more pricks the beast has, the better—in fact a dragon is the correct thing, but if that is beyond the artist, he may content himself with a lion or a pig. The beast-killing principle has been carried out everywhere with a relentless monotony, which makes some parts of Berlin look like a fossil slaughter-house.

I've recalled this passage frequently in recent years when thinking about Washington, DC. And it came to mind again after Kevin Drum passed on the latest complaints about the new Martin Luther King memorial. First the memorial was criticised for the somewhat Socialist Realist echoes of the style adopted by its Chinese sculptor, who cut his teeth on a whole lot of Mao. To be honest, I didn't quite get the criticism; I've never been able to see much of a difference between socialist realism and the tedious monumentalism of most American patriotic art. Bold men staring into the distance. Anyway, the latest problem is that the designers of the sculpture thought one of Mr King's quotes made a fitting eulogy but was too long to fit nicely on the side of the statue, so they edited it. After fierce criticism, they're now going to etch off the truncated version and put the whole thing on, in smaller letters.