Chaco signals warning for Argentina debt

A raft of Argentine provinces and municipalities suffered credit rating downgrades this week after one of their number, Chaco, in the north of the country, ran out of hard currency on the eve of a bond payment. Instead it paid creditors $260,000 in pesos. Now Chaco wants creditors to swap $30 million in dollar debt for peso bonds because it still cannot get its hands on any hard currency.

The episode is a frightening reminder of Argentina’s $100 billion debt default 10 years ago and unsurprisingly has triggered a surge in bond yields and credit default swaps (CDS). But broader questions also arise from it.

First, will debt “pesification” by some Argentine municipalities snowball to affect international bonds as well? And second, is municipal debt likely to become a problem for other emerging markets in coming months?

In Argentina, where the central bank is zealously guarding its sparse hard currency reserves, it does look likely that more provinces will follow Chaco’s example and pay creditors in pesos. But many of these municipal bonds, including Chaco’s, are governed by local law and are mostly held by Argentines. Analysts at Barclays say it is unlikely Buenos Aires will “pesify” debt issued under international law, i.e. force creditors to take payment in pesos. That’s because changing payment terms of international law paper could constitute full-fledged rather than technical default (as in Chaco’s case) and can also trigger cross default clauses. Barclays tells clients:

We believe that local law dollar debt of provincial governments and corporations will be mostly paid in pesos, as per July regulatory changes that ban exchange rate purchases without a “predetermined purpose”. But we do not expect changes in external provincial or corporate debt. Federal government local and external debt will remain honored in dollars, in our view.

The government has rejected allegations it is preparing for a full-scale debt pesification and says dollars will be made available to repay bonds. But the big test of its intentions will come on December 15 when holders of GDP warrants — debt tied to annual economic growth and paid out in pesos — are due to receive their 2012 payment. These foreign investors are wondering whether they will be allowed to convert their payments into dollars at the official exchange rate, as has been the practice in past years, or whether they will have to resort to the parallel market where the peso trades 25 percent cheaper. Amounting to $800 million at the official exchange rate, that would make a sizeable dent in central bank reserves, Barclays analysts point out.

Emerging corporate debt tips the scales

Time was when investing in emerging markets meant buying dollar bonds issued by developing countries’ governments.

How old fashioned. These days it’s more about emerging corporate bonds, if the emerging market gurus at JP Morgan are to be believed. According to them, the stock of debt from emerging market companies now exceeds that of dollar bonds issued by emerging governments for the first time ever.

JP Morgan, which runs the most widely used emerging debt indices, says its main EM corporate bond benchmark, the CEMBI Broad, now lists $469 billion in corporate bonds. That compares to $463 billion benchmarked to its main sovereign dollar bond index, the EMBI Global. In fact, the entire corporate debt market (if one also considers debt that is not eligible for the CEMBI) is now worth $974 billion, very close to the magic $1 trillion mark. Back in 2006, the figure was at$340 billion. JPM says:

Emerging debt default rates on the rise

Times are tough and unsurprisingly, default rates among emerging market companies are rising.

David Spegel, ING Bank’s head of emerging debt, has a note out, calculating that there have been $8.271 billion worth of defaults by 19 emerging market issuers so far this year — nearly double the total $4.28 billion witnessed during the whole of 2011.

And there is more to come — 208 bonds worth $75.7 billion are currently trading at yield levels classed as distressed (above 1000 basis points), Spegel says, while another 120 bonds worth $45 billion are at “stressed” levels (yields between 700 and 999 bps). Over half of the “distressed” bonds are in Latin America (see graphic below). His list suggests there could be $2.4 billion worth of additional defaults in 2012 which would bring the 2012 total to $10.7 billion. Spegel adds however that defaults would drop next year to $6.8 billion.

Yield-hungry funds lend $2bln to Ukraine

Investors just cannot get enough of emerging market bonds. Ukraine, possibly one of the weakest of the big economies in the developing world, this week returned to global capital markets for the first time in a year , selling $2 billion in 5-year dollar bonds. Investors placed orders for seven times that amount, lured doubtless by the 9.25 percent yield on offer.

Ukraine’s problems are well known, with fears even that the country could default on debt this year. The $2 billion will therefore come as a relief. But the dangers are not over yet, which might make its success on bond markets look all the more surprising.

Perhaps not. Emerging dollar debt is this year’s hot-ticket item, generating returns of over 10 percent so far in 2012. Yields in the so-called safe markets such as Germany and United States are negligible; short-term yields are even negative. So a 9.25 percent yield may look too good to resist.

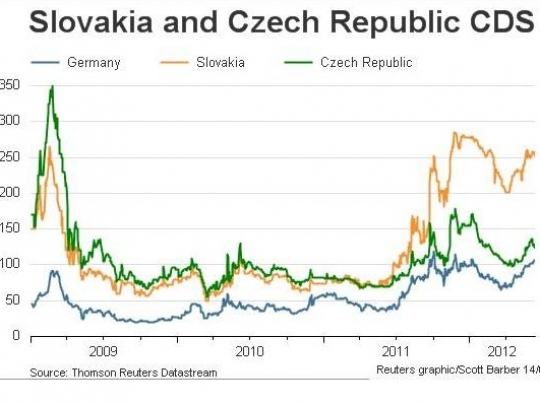

The (CDS) cost of being in the euro

What’s the damage from being a member of the euro? German credit default swaps, used to insure risk, have spiralled to record highs over 130 basis points, three times the level of a year ago amid the escalating brouhaha over Spain’s banks and Greek elections. U.S. CDS meanwhile remain around 45 bps. That means it costs 45,000 to insure $10 million worth of U.S. investments for five years, compared to $135,000 for Germany. (click the graphics to enlarge)

A smaller but similarly interesting anomaly can be found in central Europe. Take close neighbours, the Czech and Slovak Republics who are so similar they were once the same country. Both have small open economies, reliant on producing goods for export to Germany.

Emerging bond defaults on the rise, no surprise

As may be expected, the crisis has increased the risk of default by emerging market borrowers. According to estimates by ING Bank’s emerging bond guru David Spegel, the default rate on EM bonds is running at over $6 billion in the first four months of 2012, already surpassing the 2011 total of $4.3 billion. He predicts another $1.3 billion of emerging defaults to come this year.

Spegel expects the default rate for speculative grade emerging corporates to rise to 3.25 percent by September, up from 3 percent at present. That doesn’t look too bad, given defaults ran at 13 percent after the 2008 crisis and hit a record of over 30 percent in the 2001-2003 period. But ING data shows some $120 billion worth of corporate bonds trading at “distressed” or “stressed” levels, i.e. at spreads upwards of 700 basis points. The longer such wide spreads persist, the higher the probability of default. A worst case scenario would see a 12.9 percent default rate by end-2012, Spegel says.

A Hungarian default?

More on Hungary. It’s not hard to find a Hungary bear but few are more bearish than William Jackson at Capital Economics.

Jackson argues in a note today that Hungary will ultimately opt to default on its debt mountain as it has effectively exhausted all other mechanisms. Its economy has little prospect of strong growth and most of its debt is in foreign currencies so cannot be inflated away. Austerity is the other way out but Hungary’s population has been reeling from spending cuts since 2007, he says, and is unlikely to put up with more.

from MacroScope:

Greek debt – remember the goats

Greece's creditors have essentially let it off the hook by overwhelmingly agreeing to take a 74 percent loss. So what better time to remember one of the first times Athens got in trouble with paying its debts.

In 490 BC, the bucolic plains before the town of Marathon were the site of a bloodbath. Invading Persians lost a key battle against Greeks, who were led by the great Athenian warrior Kallimachos, aka Callimachus.

The trouble is, Kallimachos shares some of the difficulty with numbers that modern Greek leaders appear to have. Before launching himself upon the Persians, he pledged to sacrifice a young goat to the Gods for every enemy that was killed.

from MacroScope:

Vultures swoop on Argentina

Holdouts against a settlement of Argentina’s defaulted debt are opening a new front in their campaign for a juicy payout more than a decade after the biggest sovereign default on record.

Lobbyists for some of the investors who hold about $6 billion in Argentine debt are in London to persuade Britain to follow the lead of the United States, which last September decided to vote against new Inter American Development Bank and World Bank loans for Buenos Aires.

Washington believes Argentina, a member of the Group of 20, is not meeting its international obligations on a number of fronts. Apart from the dispute with private bond holders, Argentina has yet to agree with the Paris Club of official creditors on a rescheduling of about $9 billion of debt. It has refused to let the International Monetary Fund conduct a routine health check of the economy. And it has failed to comply with the judgments of a World Bank arbitration panel.

Beneath the Greek bailout hopes…

Who’s tired of the ”Markets up on Greece, markets down on Greece” headlines of the past few weeks? (I am.)

Today it’s an up day, with world stocks hitting a six-month peak on hopes that Greece will secure a second bailout package next week (finally, really).

But beneath the optimism lies a dire Greek economic and fiscal situation.