It's now looking extremely unlikely that Congress will enact immigration reform this year. And that raises a question: Could President Obama use his executive powers to effectively legalize some of the 11 million undocumented immigrants already in the United States?

This possibility has actually been raised several times before. Back in August, Sen. Marco Rubio warned House Republicans that if they don't pass a bill, Obama will act on his own: "I believe that this president will be tempted, if nothing happens in Congress," Rubio said, "to issue an executive order as he did for the Dream Act kids a year ago, where he basically legalizes 11 million people by the sign of a pen."

It's not just Rubio. Immigration reform advocates have been quietly discussing the possibility of executive action on legalization as a "Plan B" if the bill dies. (The White House, for its part, has shown no signs of contemplating any such move.)

So what could Obama actually do for illegal immigrants on his own? A bit, though probably not as much as Rubio suggested. In 2012, the administration was able to stop the deportation of hundreds of thousands of undocumented young adults under a deferred-action program. Obama could, in theory, expand that program somewhat, allowing even more current immigrants to work legally in the United States without fear of getting deported.

But, legal experts say, it would be extremely difficult to expand this program to cover all (or even most) of the country's 11 million undocumented immigrants. And Obama only has the power to defer deportation — he can't "legalize" immigrants on his own. That's a key distinction here. True immigration reform ultimately depends on Congress.

What Obama did back in 2012: DACA

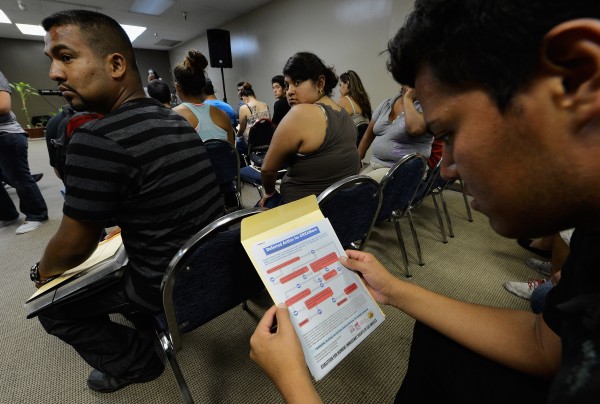

Kevork Djansezian/Getty Images - People attend an orientation class as they file their application for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program at Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles on Aug. 15, 2012.

In June, 2012, then-Secretary of Homeland Security Janet Napolitano signed a memo creating the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. This is the program Rubio was referring to.

The DACA program applies to any undocumented immigrant aged 16 to 31 who came to the United States as a child, has either graduated from high school or is currently enrolled in school, and doesn't have a criminal record. The government basically promises not to deport these youths and adults for two years and allows them to work legally in the United States. They don't get permanent residency or a path to U.S. citizenship, however — as they would have if Congress had passed the Dream Act.

As of June, the administration had received more than 550,000 applications for DACA and approved about 72 percent of them. There are another 350,000 or so youths and adults in the country who likely qualify but either don't know about the program or can't pay the $465 application fee.

The Obama administration has defended DACA as a way of rationalizing its ongoing deportation policies. After all, there are 11 million undocumented immigrants currently in the United States, and Immigrations and Customs Enforcement has said it only has the resources to deport about 400,000 of them per year. Someone has to be at the bottom of the list. DACA was a way of formalizing those priorities. The "Dream Act kids" are officially at the bottom of the list.

But there are limits to how far Obama could expand deferred-action

The legal rationale for the DACA program was outlined in a letter (pdf) drafted last year by UCLA law professor Hiroshi Motomura and co-signed by nearly 100 top legal scholars around the country. In an interview, Motomura told me that Obama could conceivably expand that program, but there are limits to how far he can go.

"Here's how I think about it. If the president can make a list to prioritize who should be deported first, then I think it’s clear that he can give people at the bottom of that list a piece of paper saying you’re at the bottom," Motomura says. "That's how I think about DACA. It's clearly within his discretionary power. But if he did this for every single immigrant, he would no longer be exercising his discretion. That would be problematic."

That means — and again, this is all just in theory — Obama could extend promises of deferred deportation to some additional groups of illegal immigrants. He could try to extend it to domestic-violence victims, say. Or to workers who are bringing civil rights or labor-violation claims. Or to those with disabled children. It's possible that these moves could cover another couple million undocumented immigrants. But he can't extend deferral to everyone.

"There's certainly room for adjustment, but not anything sweeping," says David A. Martin, a law professor at the University of Virginia and the principal deputy general counsel of the Department of Homeland Security in 2009 and 2010. "The justifications for DACA made clear that this is not a situation where the president can reduce overall enforcement of immigration laws. He can just redirect it in certain ways."

Granted, it might be difficult for anyone to sue to stop Obama if he did expand the deferred-action program. A case brought by Immigration and Customs Enforcement workers challenging DACA was recently dismissed in a federal district court in Dallas for jurisdictional reasons.

But Martin doesn't think this matters. "The administration has taken the position that you must make a good-faith effort to spend the enforcement resources that Congress has provided," he says.

Indeed, President Obama himself has said he can't do anything overly sweeping. "With respect to the notion that I can just suspend deportations through executive order, that’s just not the case," he said at a Univision town hall in 2011. Note, though, that he said all this before he signed he created the DACA program and deferred deportation for a number of youths.

Deferred-action is not legalization

Undocumented immigrants line up outside a Los Angeles Deferred Action Application Event. (The Washington Post)

There are also limits on what deferred-action can do. DACA doesn't give anyone permanent residency — the way the DREAM Act would have. It only gives them a two-year reprieve from deportation and the ability to work in the country during that time.

"It puts people in a kind of limbo," says Motomura. "The immigrants aren't on a path to permanence, their status could be revoked at any time, and they have few legal rights. If someone applies for DACA and gets rejected, there's nothing they can do. Whereas you do have legal rights if you qualify for a green card." That's one reason why many reformers would greatly prefer a bill from Congress that actually put undocumented immigrants on a path to citizenship.

Critics of DACA, however, argue that the program is actually more beneficial to immigrants than reformers think — and that the status it confers could end up being permanent. "As you might have guessed, no one has ever been sent home because his 'temporary' protected status expired," writes anti-immigration activist Mark Krikorian. "No one."

The politics of deferred action are also tricky

U.S. Customs personnel. (AP)

So far, we've just been talking about the legality of an expanded deferred-action program. Whether Obama would actually do this in practice is another question. There are good reasons to think he wouldn't.

In a leaked 2010 memo (pdf) from the Department of Homeland Security, officials actually considered and rejected the idea. The memo noted that a massive deferred-action program would have an enormous number of downsides. For instance: "The Secretary would face criticism that she is abdicating her charge to enforce the immigration laws."

The memo also noted that Congress could just block the administration's actions: "Congress could also simply negate the grant of deferred action (which by its nature is temporary and revocable) to this population. If criticism of the legitimacy of the program gains traction, many supporters of legalization may find it hard to vote against this bill."

So there are a plenty of reasons the White House might be hesitant. On the flip side, immigration-reform activists are likely to press Obama to do more if Congress really can't pass a bill that contains a path to citizenship. A few months ago in the National Journal, Fawn Johnson reported that some activists wonder if executive action might even be preferable at this point, since it wouldn't include all the measures to militarize the U.S.-Mexico border.

"The idea," Johnson writes, would be "to freeze the current undocumented population in place through an administrative order, give them work permits, and hope for a better deal under the next president, with the hope that he or she is a Democrat. It's a significant gamble, but some advocates—particularly those outside of the Washington legislative bartering system—argue that it's better than what they stand to see under the legislation being discussed now."

Update: A reader notes that NPR explored another legal avenue this summer — President Obama could use his pardon power to grant amnesty. This would be even more unprecedented than the route sketched out above (and, as such, even more unlikely). Still, that power does exist.

Note: This post was first published in August and has since been revised.