PHILADELPHIA — Every statistic tells a story.

Those stories can be simple, complex, incomplete, even seemingly contradictory at times, depending on how the numbers are tracked and presented.

The story of the four-batter sequence in the top of the fifth inning of Game 5 of the 2017 NLDS between the Nationals and Cubs — intentional walk, passed ball on a third strike, catcher’s interference, hit by pitch — was incredible in the most literal sense of the word, in that the plays’ occurrence in immediate succession strained credulity.

But perhaps more incredible than the events themselves was the fact that we could not merely be willing to bet, but know for a fact that such a sequence had never before occurred in recorded history.

None of the 2.73m half innings in our db have even had all 4 of these events. 22 w/ 3. Only 5 games had all 4.https://t.co/ntifpJIb6n

— Baseball Reference (@baseball_ref) October 13, 2017

The ability to capture such knowledge is a phenomenon of its own, a feature far beyond the capability of any single human. A monkey interminably hacking away at a typewriter might eventually yield Shakespeare, but how many eons would it take an army of poor baseball information interns to sort every inning of every box score in baseball history? For the statistics nerds among us, such power borders on the divine.

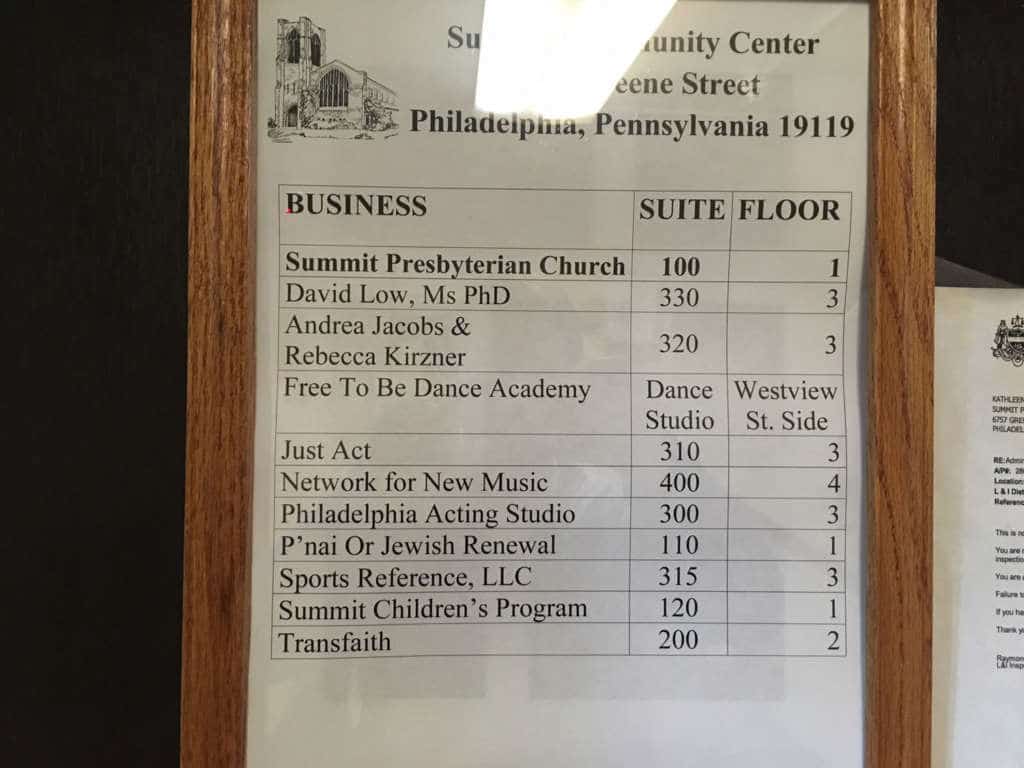

Perhaps it’s fitting, then, that the offices from which the tools that can sort 2.7 million innings of baseball history reside in the Mt. Airy neighborhood of Philadelphia, two floors above a church.

The Church of Baseball

“Bull Durham” leading lady Annie Savoy may have found her religious salvation in the Church of Baseball but statistician Sean Forman found his baseball deliverance at Summit Presbyterian.

It’s his church, the one he and his family attend, just a few blocks from their home. He used to only be here on Sundays, back when he was a math professor at St. Joseph’s University, when the piles of Excel spreadsheets he would update at the end of each baseball season represented just a hobby, not the nerve center of sports information for fans and professionals alike.

The passion was born out of boredom and idle hands back in the spring of 2000 when Forman’s wife, who finished her graduate program at the University of Iowa a year ahead of him, landed a job at Mercer University in Macon, Georgia.

“I was in Macon and kind of bored out of my mind. My adviser was in Italy, and I didn’t have any teaching or anything, so I created Baseball Reference kind of that year when I was at loose ends in Georgia,” Forman told WTOP in an interview in his office.

In the frame of baseball’s statistical revolution, the timing was perfect.

The “Moneyball” Oakland Athletics were driving the beginning of the game’s massive investment into analytics. But in the larger scope of the economy, particularly online, it couldn’t have been worse. Baseball Reference was born into the smoldering ashes of the dot com bubble burst.

“I joked that if we started our sites a year earlier we’d be Mark Cuban right now,” Forman said.

A friend of Forman’s and fellow statistician Sean Lahman unlocked the beginning of what would eventually turn into the site that exists today.

“Total Baseball included a CD-ROM in one of their versions, which was not well-protected,” Forman said. “And (Lahman) basically kind of cracked in and got the stats out of it, and called it The Baseball Archive … I kind of used that as the basis for the site and built all the basic pages out of that.”

After landing his job as a math professor at St. Joseph’s, Forman was paying just $25 a month for a hosting platform for his hobby when, about a year in, the site was mentioned in Sports Illustrated.

Traffic spiked so quickly it crashed the site out of commission.

“The site cratered,” Forman said. “We were down for like three weeks, I think.”

He bumped up to a $300-$400/month new server, with no ads, the site being supported in the NPR style, made possible through generous donations from dedicated baseball nerds like you.

For six years, the site was updated only at the end of the baseball season, a passion project that took a few weeks each year to maintain. Fans used to be able to sponsor player pages, but that was phased out as traffic picked up. Eventually, ad revenue was stable enough that Forman realized it was a viable enough enterprise to consider full time, shifting to a database he would update daily.

In 2006, with an infant son and despite a tenured position, he took a leave of absence, rented an office above the church, and took a leap of faith.

“I’m sure from the outside my parents, my in-laws, thought it was kind of nuts,” he said. “My father-in-law had gotten tenure at one place, then moved, then not gotten tenure, so I’m sure he thought it was ridiculously irresponsible.”

Forman acquired Doug Drinen’s Pro Football Reference (2000) and Justin Kubatko’s Basketball Reference (2004) and brought them under the Sports Reference umbrella. Today, that portfolio also includes hockey, college football, and college basketball.

While most employees that have been added as the site has expanded have stayed on, a couple have moved into other parts of the industry.

Former intern Ben Zauzmer was hired by the Los Angeles Dodgers and is now their coordinator of baseball analytics. Neil Paine was one of the first to join Nate Silver at FiveThirtyEight, after the site migrated to ESPN.

Eventually, as the site grew, Forman moved across the hall into the offices he now occupies, a modest set of gray cubicles and bookshelves tucked between a dance studio and a meditation instructor.

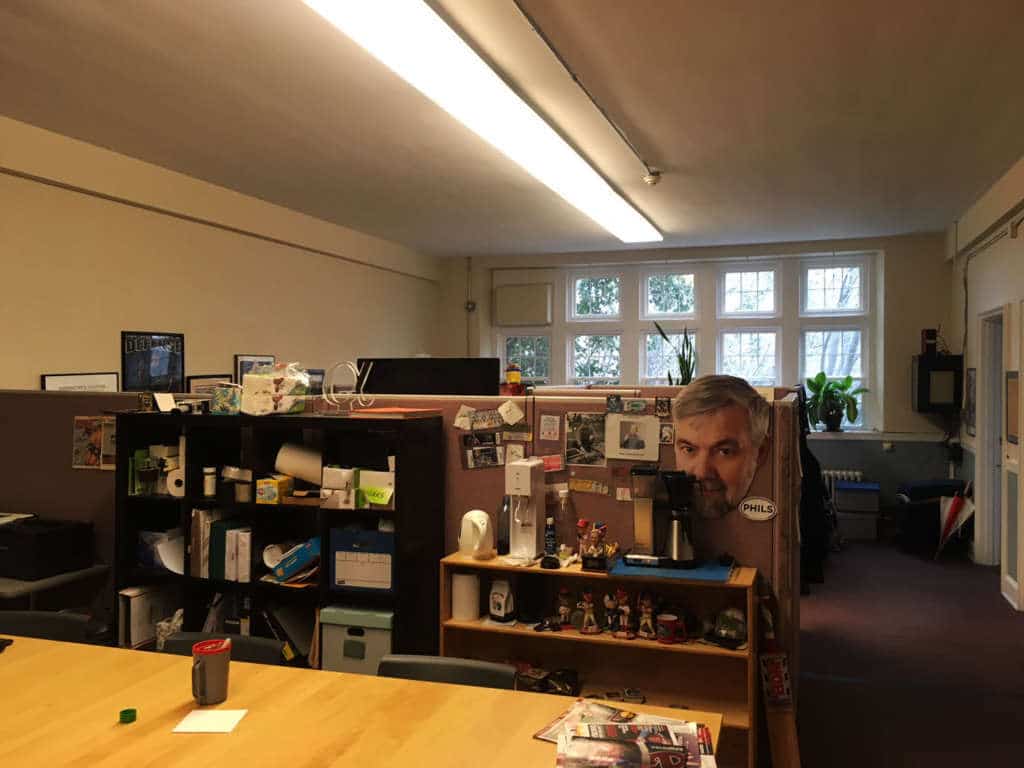

The Creator

The sites prioritize function entirely over form. Like Ken Pomeroy’s college basketball site, you can almost see the Excel spreadsheet cells within the pages. That makes sense, given their creator.

Forman looks the part of a former math professor — blue-checked dress shirt tucked into relaxed jeans, loosely kempt beard somewhere between stubble and hipster, intent eyes behind black, square-rimmed glasses. There’s some Iowa left in his vowels, but it’s mostly been smoothed out after nearly two decades on the East Coast. His office is full of white boards with notes and Post-its, various abbreviations scribbled on them. For privacy, I don’t take any photos, but while each scribble surely signifies something to him (and perhaps to others in his field), I wouldn’t know what any of it means anyway.

One might expect a company that works largely in digital databases to be remote, its employees connected only virtually. But all but one of the employees are local — the impeccably named Baseball Reference operations manager Hans Van Slooten lives in St. Paul, Minnesota, and one other employee lives in Baltimore and commutes up to Philly one day a week.

“Obviously, with the technology, you can work remotely,” Forman said. “I’ve come around to kind of the view that having face-to-face interactions are more beneficial than (doing) everything on a Slack channel.”

That’s not the only way in which Forman bucks the image some reactionaries love to conjure of some nerd who never played the game and only sees sports through the prism of a bunch of spreadsheets. The son of a high school football coach, Forman played baseball and football through the prep ranks, but was involved beyond the field of play. In middle school, he helped his dad compile the box scores after games and later dabbled in sports writing.

But he certainly has the mind of a mathematician. An example: One of the minor improvements he’s made on Basketball Reference over the years is on the position sorting tab, making it sort from smallest to largest position on the court, rather than alphabetically.

“So now it sorts by point guard, shooting guard, small forward, power forward, center, instead of center … whatever that would be alphabetically,” he explained.

The point that the new order is cleaner is made simply by the fact that he’s not immediately able to conjure the unnatural, alphabetical order that used to be. But rather than move on, he does the sorting anyway.

“I guess, you know, center, power forward, point guard, shooting guard, small forward,” he says, and it’s right, even if it looks like power forward and point guard are out of order, because they are listed by abbreviation (PF, PG), and it’s important that the distinction is made and made correctly. When so many important entities rely on your accuracy for their own record keeping, it’s a point that no longer seems trivial, but rather one you would expect to be made.

‘I didn’t know you could do that’

Why is the site so popular?

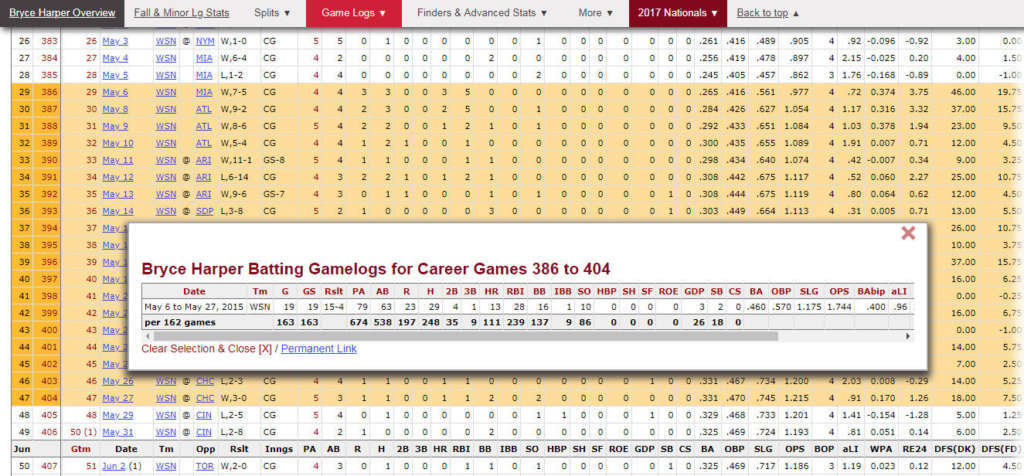

Let’s say, for instance, that you wanted to know exactly how good Stephen Strasburg was after coming back from the disabled list in August of last year. Or, if you’re trying to isolate Kirk Cousins’ struggles late in games when he’s trying to rally back, you can find that he has completed 37-59 passes with no touchdowns and four interceptions in his career when trailing with fewer than two minutes remaining. Perhaps you’re trying to verify that John Wall is the only NBA player to average better than 10 assists per game each of the last three seasons. No matter the question, there’s a good chance there’s a way to find the answer.

“There were things users were pointing out that you could do with the tools where I was like, ‘I didn’t know you could do that,’ and I built the site,” said Forman.

An informal survey of a half dozen Major League media departments in both leagues from coast to coast found that each and every one of them leaned on a combination of Baseball Reference and an expensive, paid service, like STATS Pass. Both the Nationals and Orioles MASN broadcast production teams visit the site with regularity for player information.

But perhaps the most ringing of endorsements come from the broadcasting voices that bring you the games.

“Baseball Reference has changed how I, and many others, prep for a game,” said Brian Anderson who, in addition to his work as TV play-by-play man for the Milwaukee Brewers, calls MLB games for TBS, NCAA games for CBS and Big Ten Network, and NBA games for TNT. “It’s part of my routine. I’d be lost without it.”

Anderson leans particularly on the game logs and transaction histories in his game prep, and finds himself visiting the site in-game, on the air, for quick information on relief pitchers and pinch hitters that come into the game.

“Anyone who is ‘new’ to the game and not on my pre game prep sheet, I lean heavily on BR,” he said.

That sentiment seems common among the baseball broadcasting world.

Kevin Burkhardt hosts MLB Whiparound and calls NFL games on FOX Sports, but he used to cover the Mets as a sideline reporter for SNY. When he broke in back in 2007, he discovered that others were using the site and couldn’t believe what he found when he dove in.

“I was like, ‘oh my God, this thing’s amazing,’” Burkhardt said. “I’m on the site all the time, all the time … It’s the best resource on the ‘net.”

For Nationals fans, Baseball Reference plays a significant role in the way they consume the game, whether they’ve ever even heard of the site. The radio tandem of Charlie Slowes and Dave Jageler both lean on it heavily, especially for opposition research as the season wears on and media guides become dated.

“To me, if that site were down, my preparation would take a major, major hit,” Jageler said.

“Probably a day doesn’t go by during the season that we don’t use it for something,” said Slowes, who also recently found himself on the Hockey Reference site, confirming stats about Alex Ovechkin before a recent broadcast.

The first tab on Jageler’s iPad remains permanently open to Baseball Reference. When asked a recent time he found himself going to the site, he recalls the game this past weekend, as the duo called their first Spring Training broadcast of the new season.

Conversation strayed from the action on the field to longtime minor league players who stay in one spot so long they develop a cachet in certain towns. Jageler reminisced about Stu Pederson, father of Joc Pederson, who had all of eight big league at-bats, but was a legend in Syracuse, where he played more than 400 games with the Chiefs during the time Jageler was in college there. That prompted Slowes to bring up another pitcher whose name, upon retelling the story to WTOP, Jageler can’t remember. So he does what he did during the game — he grabs his iPad and pulls up the site to reveal that it was Ed Glynn, the “Flushing Flash.”

“When Dave says, ‘we’ll get the interns on that,’ he really means one of us is on Baseball Reference,” Slowes said.

The future

Perhaps surprisingly, none of the broadcasters interviewed pay for the detailed sorting Play Index portion of the site, the only part that isn’t free.

At $36 a year, it’s less than the cost of The Athletic and vastly cheaper than the STATS Pass programs that MLB clubs use, which can run upward of $10,000 per subscription.

“We should probably up what we charge,” Forman joked.

For whatever reason, that side of the site hasn’t caught on as much, though with the possibility of legalized sports gambling resting with the Supreme Court, there may soon be a bigger market for that detailed level of information. Forman describes the subscriber base as “in the thousands, but not the tens of thousands.” Still the site’s traffic has continued to grow steadily, between five and 40 percent each year, driving revenue through advertising.

A traffic analysis shows Baseball Reference to be the third most popular baseball site on the web, behind only MLB.com and MLBTradeRumors.com.

Basketball Reference, which Forman says has grown exponentially in recent years, is pulling down more than 12 million visits per month during the season. With the growth in interest in analytics and the global popularity of the game in general, Forman thinks it might actually overtake the baseball side in overall traffic.

Sports Reference is not an overnight success story, but it is a self-made one. It wasn’t venture capital-backed, nor does it take out big, splashy ads during major broadcasts. There have been chances to sell the platform, but ultimately Forman has stuck it out.

“We’ve had opportunities along the way to do that and it’s never quite felt right to me.”

Meanwhile, the sports information industry has grown up around him. Forman actually attended the very first MIT Sports Sloan Analytics Conference, back when it was held in the basement of the MIT math building and featured more speakers than attendees. In 2013, Sports Reference received the conference’s Alpha Award for Best Analytics Innovation/Technology. And while that honor may continue to rise in its widespread prestige as the conference gains traction in the mainstream, Forman doesn’t find much personal use in Sloan’s existence anymore.

“My view is it’s become much more a sports business conference instead of a sports analytics conference,” he said. “I mean, the fact that the commissioners are there speaking, and team owners, I always kind of cringe at those talks. Because those people are very rarely giving you anything of value to pushing the field forward. I come from a more academic background where you share what you learn, you publish, and things like that.”

Forman still sent an employee this year, but he’s got plenty of other items occupying him these days. With two new hires, the staff has expanded to 10 and will soon be annexing the original office space, back across the hall. His next big project? Soccer, a sport of unprecedented breadth.

To wit: Tim Locastro, an outfielder for the Los Angeles Dodgers, is the 19,175th and most recent player to make his Major League debut, on Sept. 29 last season. In other words, in the history of Major League Baseball, there have been fewer than 20,000 total players. Wikipedia lists more than 22,000 professional soccer teams worldwide.

The plan is to track all the way down through League 2 in England, USL in America. But promotion and relegation bring new challenges, tracking teams across levels as they’ve risen and fallen over time. Even with two people assigned to the sport, Forman thinks it could take as long as five years to fill in all the data.

That may seem a herculean undertaking. But at Sports Reference, that’s just what they do.