In the face of prejudice and discrimination throughout history, members of the LGBTQ+ community developed secret coded languages to help them connect, interact or record their experiences.

Some of these evolved out of a need for members of the community to be able to communicate safely with each other, such as Polari. Others were far more personal.

In the case of Anne Lister, nicknamed Gentleman Jack, creating a complex code for her journal entries allowed her to express her thoughts more freely.

We take a look at an example of both, from different periods of UK history.

What is Polari?

Until 1967, homosexuality between men was illegal in the UK. Anyone who broke the law could face a lengthy jail sentence. Forced into secrecy, gay and bisexual men developed their own way of communicating with each other safely. This language is called Polari.

You’re probably already familiar with a few terms that have crossed over into the mainstream, such as bevvy (a beverage) or scarper (to run off). But where did they come from?

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, Polari originates from the 18th and 19th Centuries, where it was used by various groups, including circus people and other travelling performers, Roma people, sailors and criminals. Many of these groups were marginalised by society. The strong Italian influence is clear in the name, as Polari derives from the Italian verb parlare, meaning to speak.

Due to this wide array of influences, within Polari there are often different spellings, pronunciations and even meanings.

When and where was the Polari language used?

By the 20th century, it was being used by gay men working in London’s theatre district, the West End. Bits of US slang were also added when American soldiers (known as G.I.s) were posted to the UK during World War Two.

Whilst some of the language is certainly suggestive in nature, it could also be used for everyday conversation. As a gay man, you might slip a word or two of Polari into conversation and look for a reaction, to see if someone was also a member of the community.

Image source, BBC

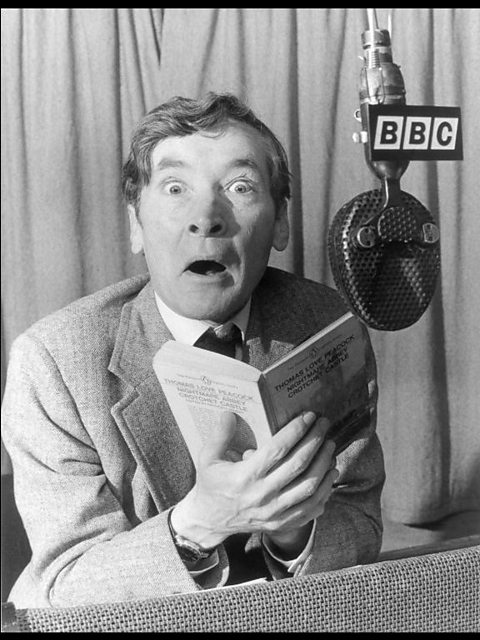

Image source, BBCHumour is prominent in Polari, whether used to insult someone or make people laugh, but in order to get the joke, you have to know the language and its nuances.

At one point, Polari even featured prominently on the BBC. Round the Horne was a BBC Radio comedy, starring Kenneth Williams and Hugh Paddick, which ran from 1965 to 1968. Their characters would frequently pepper their conversations with Polari slang, which the show’s writers were able to get past the censors. This was thanks in part to the backing of the BBC’s director general Sir Hugh Greene.

This boundary-pushing show was incredibly popular, regularly reaching over 15 million listeners. However, it came at a point at which Polari usage was beginning to decline. The decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1967, between men aged over 21, reduced the need for such covert communications and so it was used less frequently in the 1970s and 1980s.

Image source, BBC

Image source, BBC

A glossary of the Polari language

- Bijou- small

- Bona- good

- Dolly- attractive

- Eek/ecaf- face

- Fantabulosa- wonderful

- Handbag/hambag- money

- Kaffies- trousers

- Ogle fakes- glasses

- Onk- nose

- Riah- hair

- Riah shusher/crimper- hairdresser

- Slap- makeup

- Zhoosh/zhush/zhuzh/jhoosh- to smarten up, to style something

Who was Anne Lister?

Whilst female homosexuality was never technically illegal in the UK, it was certainly still frowned upon. It’s not surprising then, that the early 19th Century Yorkshire landowner and diarist Anne Lister, chose to use a code to write about her romantic experiences with other women.

Anne was meticulous in recording the details of her daily life for several decades, so much so that her diaries run to over four million words. Of these approximately one sixth are written in code, which she referred to as ‘crypt hand’. It is comprised of Greek and Latin letters, numbers and symbols.

Image source, MCPIX/Shutterstock

Image source, MCPIX/ShutterstockHidden within this code, Anne charts the highs and lows of her relationships with a number of different women — from her five year relationship with Mariana Belcombe, who broke her heart by marrying a man, to more short-lived affairs, and finally her union with a local heiress, Ann Walker.

Anne Lister’s coded diaries

Ann’s wealth was certainly part of the attraction, but Anne’s coded diary entries outline how quickly she became infatuated. Eventually, Ann moved into Shibden Hall with Anne and the two women chose to demonstrate their commitment by exchanging rings on Easter Sunday 1834 in a symbolic church ceremony at Holy Trinity church in York. They also altered their wills, giving each other life tenancy of their respective estates.

Reflecting on her attraction to women, Anne refers to it as her ‘oddity’, but one that she felt was completely natural. She writes on the 29 January 1821: ‘I love and only love the fairer sex and thus beloved by them in turn, my heart revolts from any other love than theirs.’

As well as describing her lesbian relationships, Anne used the code to record details of her health and financial matters. Doing so appears to have given her a sense of release. Writing on the 29 April 1832, she states: ‘What a comfort my journal is. How I can write in crypt all as it really is and throw off my mind and console myself. I thank God for it.’

When the code was first broken in the 1890s by Anne’s descendent John Lister, along with Arthur Burrell, he chose to keep the diaries a secret in order to avoid a scandal. The diaries were rediscovered upon John’s death in 1933, but the contents were once again suppressed.

It was only when historian Helena Whitbread took up the challenge of decoding the diaries in 1982, that their full contents were made public. The diaries were deemed to be of such importance that the United Nations formally recognised them as a ‘pivotal document’, voting to include them in an online archive of historic UK materials.

Image source, MCPIX/Shutterstock

Image source, MCPIX/ShutterstockPride Month: Six symbols of pride

We look at some modern and historic symbols of alliance, protest and pride.

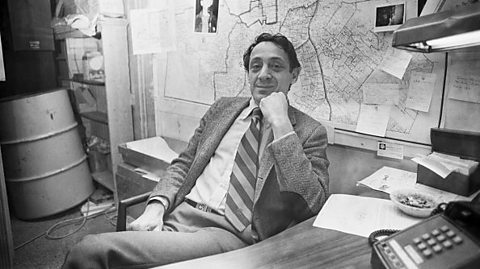

The LGBT icons you need to know about

They took a stand in an attempt to bring about change.

The evolution of LGBT+ History Month

We look at how LGBT+ History Month has changed since its creation.