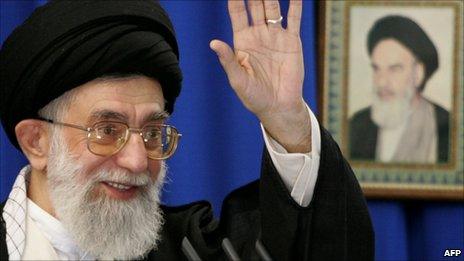

Profile: Iran's 'unremarkable' supreme leader Ayatollah Khamenei

- Published

"I have a poor soul, an incomplete body, and the little bit of dignity that you have given me - I will sacrifice it all for the Revolution and for Islam," Ayatollah Ali Khamenei said in 2009.

In Iran, the word of Ali Khamenei is absolute. For more than two decades he has been his country's supreme leader.

But the outside world knows perhaps only two things about him: he has almost the same name as the man he replaced, Ayatollah Khomeini, and he is overshadowed by the man he outranks - President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

When we do see Ali Khamenei he is often delivering a sermon against the US - looking rather forbidding in a black turban and white beard.

But it turns out that this same man also smoked a pipe, likes gardening and enjoys poetry. It is time to get to know the ayatollah.

Cleric at 11

Ali Khamenei was born in 1939 in the northern city of Mashhad - the holiest city in Iran.

He followed his father and became a cleric. It was not an easy choice. He grew up during the rule of the Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. The Shah was a secular monarch who viewed religion as ancient and suspicious.

"Khamenei became a cleric when he was very young, at the age of 11," said Mehdi Khalaji, who is writing a biography of the ayatollah.

"He wore the clerical uniform which was very difficult for him when he was playing with children on the streets. People were mocking him because of the special period in which he was living in Mashhad. He had a very difficult life."

But Ali Khamenei kept going. He got married and had six children (we have pictures of his sons, but none of his wife or daughters). Some members of his extended family now live outside Iran.

His nephew, Mahmood Moradkhani, is in exile in Paris. He remembers his uncle as a quiet man who loved poetry.

"He was very nice and sociable," said Mr Moradkhani.

"Interestingly though, in my memories he was unremarkable. He didn't stand out in any way. He was very ordinary. For example, people from Mashhad have poetic tendencies. All Iranians have a poetry notebook, and we all love the arts."

The marxist and the cleric

In his early years, Ali Khamenei also liked to smoke cigarettes and even a pipe - a very unusual habit for a religious man.

He also supported the Shah's main enemy - exiled cleric Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. The ayatollah wanted to bring Islamic rule to Iran.

Ali Khamenei tried to spread the ayatollah's message inside the country. For this the shah's police arrested him six times.

During the 1970s, Marxist groups were also trying to get rid of the shah. So, the cleric Ali Khamenei ended up sharing a prison cell with Houshang Asadi, a young communist. The cleric and the communist got on quite well.

"He was a very good man," said Mr Asadi.

"He joked about very, very small things that [had nothing to do] with sexuality."

"Did you ever think he would end up as the supreme leader of Iran?" I asked.

"Never and never and never and never," Mr Asadi replied.

Hostage crisis

But 1979 changed everything. The Shah fell. Ayatollah Khomeini stepped off the plane from Paris, and founded the Islamic Republic. Iran was to be ruled by clerics. And Ali Khamenei was one of them.

The 40-year-old became a member of the new ruler's inner circle. He was made leader of Friday prayers in Tehran.

He was even sent to play a part in the defining event of the Revolution - the takeover of the US Embassy in Tehran.

Iranian students held more than 50 US diplomats hostage. The hostages included political officer John Limbert. One afternoon, five months into his captivity, he had an unannounced visitor - Ali Khamenei.

"It wasn't a meeting that I requested," remembers John Limbert.

The two men spent about 10 minutes talking. Their conversation was recorded by Iranian state TV.

"What I wanted to do was use what I knew of Iran and Iranians as a kind of leverage against him," said Mr Limbert.

"So when he said for example, 'Do you have any complaints?' I said, 'Well the students have overdone traditional Iranian hospitality. I know that Iranians do not want their guests to leave but this is really ridiculous.' He was clearly not a stupid person. He knew that I was taunting him."

After the bomb

But soon Ali Khamenei had bigger things on his mind. In June 1981, an opposition group tried to assassinate him. A bomb hidden inside a tape recorder detonated while he was giving a news conference. He lost the use of his right arm.

"I was in pretty bad shape after the attack," Ali Khamenei later told an audience in Tehran, "because no-one thought I would survive.

"I felt that I was at death's door. In the days that followed, I thought 'Why have I survived?' And it dawned on me that our heavenly God wanted me to survive for a reason."

While he was still recovering he was elected president. It was a powerless, thankless job. During these years he was seen as a dogged, faithful follower.

Then in June 1989 Ayatollah Khomeini died. Clerics met to pick a new leader. Ali Khamenei emerged as an inoffensive consensus candidate.

He was only 49 years old. But he looked much, much older. He was chosen in order to follow the ideas of Ayatollah Khomeini - not to suggest his own.

"He is a very ordinary man and I think that's the key for his success," said his biographer Mehdi Khalaji.

"He planned everything, he thought about everything. When he became a leader he had nothing.

"One of the main things he did was a very precise and subtle plan to empower the Revolutionary Guard after the Iran-Iraq war and by relying on them and empowering them he consolidated his own power and became a very strong leader."

Absolute power

Ali Khamenei now has the same absolute power as the shah had in the 60s and 70s. But he leads a very different life from the last ruler of the Pahlavi dynasty.

The Shah travelled around the world and enjoyed banquets and horse-drawn carriages. Ali Khamenei never leaves Iran. His greatest extravagance appears to be tending to a small garden - one photo shows him happily using a plastic watering can.

Ali Khamenei's former cellmate Houshang Asadi has watched the ayatollah's assumption of absolute power with great disappointment.

In the 70s, the cleric and the communist had fought together for an end to the rule of the shah. Now the communist believes that his former cellmate has betrayed the cause for which the two men once fought.

"He changed from a man who fought for freedom to a dictator, now Mr Khamenei is more of a dictator than a shah," he said.

"If you met him now what would you say to him?" I asked.

"First I say, 'I don't know you. Who are you Mr Khamenei?' Because when you [become] a dictator your ears are closed, your eyes are blind - you can't see anything and you can't hear anything."

Last leader?

But the ayatollah retains the loyalty of the Revolutionary Guard - the force that keeps him in power.

Ali Khamenei has now ruled Iran for twice as long as Ayatollah Khomeini before him. He is 72 years old. When he dies, will Iran search for its third supreme leader?

"It's increasingly difficult to believe in the 21st Century that this very young, modern Iranian population is going to be willing to be ruled by a supreme leader who purports to be God's representative on Earth," said Karim Sadjadpour from the Carnegie Endowment in Washington DC.

"So I think it's certainly within the realm of possibility that Ayatollah Khamenei will be Iran's last supreme leader."

But the ayatollah will fight to pass on the system he inherited.

If there is any conflict within him, it is hidden well away. If he has any doubt, Ali Khamenei will not share it.

He has been a cleric for 60 years, and the guardian of a religious revolution for more than 20. In the end, it is to God alone that the supreme leader feels he must answer.

- Published8 July 2011

- Published2 March 2011

- Published4 August 2010

- Published9 June 2009

- Published10 May 2011