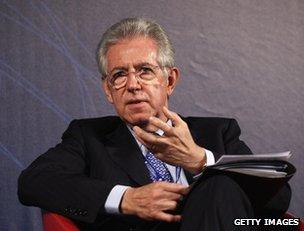

Profile: Mario Monti

- Published

Mario Monti is a distinguished economist and Brussels veteran who was drafted in as Italy's prime minister amid high political drama and financial uncertainty in late 2011.

An understated and unelected technocrat with a reputation as a tough negotiator, he calmed the markets and pushed through some rapid reforms before running up against resistance from economic lobbies and political parties.

After a little more than a year in the job Mr Monti announced he would step down when the man he replaced as prime minster, Silvio Berlusconi, withdrew his party's support for the government.

When announcing his resignation in December 2012 he declared "mission accomplished", having put a lid on the Italian debt crisis.

But it seemed unlikely that Mr Monti, 69, would retire from the turbulence of politics in Rome.

Regarded as a possible leader or senior member of a new centrist coalition following elections coming up in February 2013, he is also seen as a potential future candidate for the post of president.

'Super Mario'

Mario Monti was born in 1943, in the northern Italian town of Varese, in the wealthy region of Lombardy.

He studied economics at the highly rated Bocconi University in Milan, and Yale in the United States.

At Yale, he studied under James Tobin, inventor of the "Tobin tax", also called the "Robin Hood tax" - a proposal to tax financial transactions so as to limit speculation.

He taught economics at the University of Turin for 15 years before returning to Bocconi as rector in 1984.

In 1994, he was appointed the EU commissioner for the internal market and services.

He was nominated by Mr Berlusconi, then serving his first term as prime minister.

It was in his second term at the commission (1999-2004) that he earned the nickname "Super Mario" for the way he took on vested interests.

He blocked a merger between General Electric and Honeywell, and battled Germany's powerful regional banks.

He also launched an anti-trust case against Microsoft for its bundling of audio and video software. In 2004, the EU fined Microsoft 497m euros (£325m) for what it said was abuse of its dominant market position.

European integration

Mr Monti was nominated for his second term in Brussels by centre-left Prime Minister Massimo D'Alema.

But by 2004, Mr Berlusconi was back in power. He refused to back the soft-spoken economist for a further stint.

In 2005, Mr Monti founded the Brussels-based Bruegel think tank, specialising in economic policy. He returned to Bocconi University, this time as president.

In 2010, Mr Monti was one of the founders of a European federalist initiative known as the Spinelli Group, which seeks to promote greater EU integration. Other members include former commission president Jacques Delors, former German foreign minister Joschka Fischer and Green MEP Daniel Cohn-Bendit.

He also wrote a report for Brussels on the future of the EU single market, which was published in 2010.

"He has experience and, Europe-wide, is one of the most highly esteemed Italian personalities," Gianfranco Fini, speaker of the lower chamber of the Italian parliament, has said of him.

It was to Mr Monti that Italian President Giorgio Napolitano turned when Mr Berlusconi resigned in November 2011, as financial markets piled pressure on Italy.

Mr Monti was swiftly sworn in as a senator for life, allowing his nomination as the head of the government.

In power, he made some progress with economic policy early on, including raising the retirement age and structural reforms.

But later policies were watered down and Mr Berlusconi and his centre-right People of Freedom (PDL) party increasingly attacked Mr Monti's economic austerity.

Mr Monti had planned to serve until April 2013, hoping that would give him time to "rescue Italy from financial ruin".

But once Mr Berlusconi pulled his support, Mr Monti was left with little choice other than to announce his intention to resign.

Mr Monti and his centrist alliance are not expected to win the elections, but they could be crucial in providing the left-wing Democratic Party with a majority in the upper house.

- Published21 December 2012

- Published9 December 2012

- Published14 November 2011

- Published3 November 2011

- Published9 November 2011