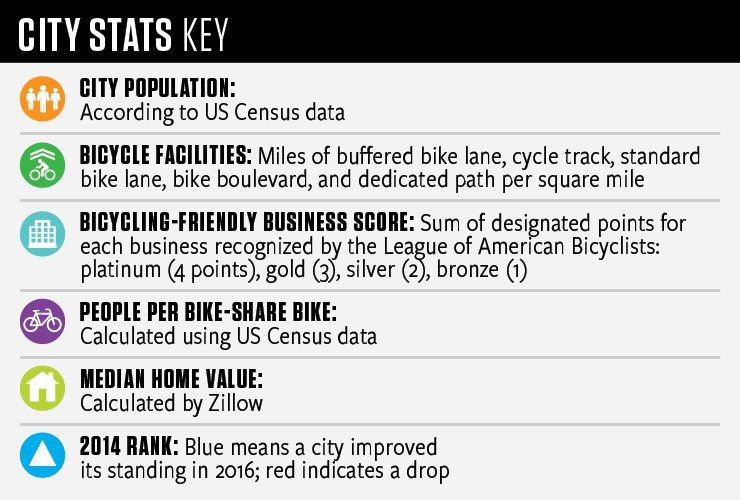

Every two years, we sift through Census and department of transportation data on more than 100 cities, consult with experts from organizations such as People for Bikes, the Alliance for Biking & Walking, and the League of American Bicyclists, and talk with bike advocates and everyday riders to identify the 50 most bike-friendly towns in the United States. We look at everything from miles of bike lanes to the percentage of cycling commuters who are female—a key indicator of safe bike infrastructure—to the number of cyclist-friendly bars. The goal is not only to help you plan your next relocation but also to inspire riders and municipalities to advocate for change. (“Shaming works,” admits one city planner we spoke to this year.) Here are the 50 cities that made the cut this year—how does your town measure up?

Additional reporting by Danielle Zickl

1: Chicago

In April, shortly after his re-election, Mayor Rahm Emanuel announced Chicago would build 50 miles of bikeways—many of them physically separated from motor vehicles—over the next three years. Such proclamations can come easily (and cheaply) to the lips of politicians, but during his first term in 2015, Emanuel made good on a promise to build 100 miles of buffered and protected bike lanes. “Those initial 100 miles of bike lanes cost just $12 million,” says Jim Merrell, advocacy director for the Active Transportation Alliance. “That highlights the cost effectiveness of transformative transportation projects like these.”

When its protected bike lanes are completed in spring 2017 in conjunction with its Loop Link transit project, Chicago will become the first major U.S. city with a downtown network of protected bike lanes—a major boost to the nation’s second-largest bike share system, Divvy. Further, many of Chicago’s existing bollard-protected bike lanes are currently being rebuilt with concrete curbs. This includes the state-owned Clybourn Avenue, a heavily used but dangerous corridor that the city had long pressured the Illinois DOT to rebuild. “The curb protection is aesthetically pleasing, and durable in a city with intense weather,” says Merrell. Plus, the concrete barriers also send an important message: Chicago’s commitment to safe and low-stress cycling is permanent.

The city also recently unveiled a program called Divvy For Everyone, which subsidizes bike-share memberships for low-income residents. A new 35th Street bridge, spanning a tangle of rail lines, will link the traditionally African-American community of Bronzeville to the Lakefront Trail. And the Big Marsh Bike Park, a former industrial wasteland in southeastern Chicago, will open in the fall of 2016 with flow and singletrack mountain bike trails, pump tracks, and a cyclocross course.

Local Advice

For inexpensive tune-ups, women’s repair classes, and Sunday social rides, visit Bronzeville Bikes, a shipping container turned community bike shop.

2: San Francisco

Over the last four years, San Francisco has added miles of new and high quality cycling facilities, and seen a resulting surge in ridership. According to the most recent Census data, the number of people commuting by bike in San Francisco increased by 16 percent between 2012 and 2014. On the busy Market Street bike lane, a bike counter that records the number of trips taken annually hit one million for the first time in 2015. And this year, the city broke ground on a number of transformative projects, including a protected bike lane on Masonic Avenue. In 2017 the city plans to add raised and protected bike lanes on Second Street, which connects to a main transit hub. The Second Street improvements will turn the corridor from a “traffic sewer, into a dream,” says Chris Cassidy, communications director of the San Francisco Bicycle Coalition.

The city’s 2014 commitment to a Vision Zero policy (the goal of which is to eliminate all traffic fatalities), brought statistical analysis of the most dangerous streets, and pointed improvements. For example, planners recently retrofitted a high-injury corridor on 13th Street with a parking-protected bike lane (in which cyclists are separated from automobile traffic by a row of parked cars). However, many local advocates remain frustrated with the police department’s misguided enforcement efforts. A crackdown along the popular “Wiggle” bike route in 2015 saw police ticket hundreds of cyclists who failed to put their feet down at stop signs. Riders responded by staging a mass protest and call for meaningful enforcement, as statistically, bike riders rarely cause traffic deaths.

The battle turned political when, siding with cyclists, the city’s Board of Supervisors passed the first stop-as-yield ordinance in a major American city—allowing bike riders to yield at stop signs when conditions are safe to do so—only to have the mayor veto the measure.

In 2015, San Francisco installed 800 new bike racks, including one bike corral that doubles as a city mural. And, in 2017, when the Bay Area Bike Share completes a massive expansion, San Francisco will boast one of the nation’s densest bike share networks, with 4,500 bikes in the city itself and more than 7,000 across the region.

Local Advice

Angel Island State Park was once used by Native Americans for hunting and fishing. During the Civil War the land mass was fortified with batteries to defend against the threat of the Confederate navy, and in the early 1900s the island became an immigration center—the Ellis Island of the west. Today, the state park is easily accessed via ferry ($8 one way, $1 extra for bikes) from San Francisco’s Pier 41. Roughly 8 miles of car-free paved and dirt roads circle the island, providing panoramic views of the Golden Gate Bridge and the city’s skyline. There are also a handful of campsites where you can pitch a tent, then watch the sun set over the San Francisco Bay.

3: Portland, Oregon

“The last year and a half has been very good for biking in Portland,” says Rob Sadowsky, director of the Bicycle Transportation Alliance, Oregon’s primary advocacy group. According to US Census data, the percentage of residents who commute by bike increased by 27 percent between 2013 and 2014 to 7.2 percent in total. The city gained national acclaim upon the opening of the Tilikum Crossing over the Willamette River, a bridge that carries busses, trains, cyclists and pedestrians—but not cars. And Nike kicked in $10 million to the city’s new Biketown bike share system, nearly doubling its capacity to 1,000 bikes. According to Sadowsky, however, the city really “won the day” upon unveiling its Vision Zero plan, which included a map showing every crash in Portland between 2005 and 2014. City council is to vote on the policy October 14; Sadowsky predicts it will pass unanimously. In 2015, Portland’s head of transportation, Leah Treat (an acolyte of transformative city planner Gabe Klein) mandated protected bike lanes be the default design for all new and redesigned road projects.

RELATED: Why Portland Remains a Paragon of Bike-Friendliness

The city is aiming to complete its 20s bikeway in 2017, adding 9 more miles to its 86-mile network of streets prioritizing bike riders. And, while Portland still lacks a robust downtown bike infrastructure to complement its new bike share system, in May, voters approved a 10-cent gas tax, the state’s highest gas levy. The funding will provide $28 million over four years directly to bicycling and pedestrian improvements, including $8.2 million dedicated to protected bike lanes in the central city.

Local Advice

Portland’s annual summer celebration of bikes, PedalPalooza, lasts over three weeks and is about as close to cycling nirvana as one can get, with nearly 300 organized rides, parties, and bike-related activities—for example, an impromptu cook-out with a bike-mounted grill.

4: New York City

The 2013 election of mayor Bill de Blasio brought one of the nation’s most robust (and much needed) Vision Zero policies. Following the citywide reduction of speed limits to 25 mph, traffic fatalities subsequently fell 22 percent. As part of the safety initiative, de Blasio committed $100 million to the redevelopment and installation of protected bike lanes on Queens Boulevard (known to locals as the “Boulevard of Death”). While traffic enforcement still varies precinct-by-precinct, the police department’s ticket blitzes—including one in Lower Manhattan that saw 12,000 violations handed out for speeding, texting while driving, and failing to yield—have proved effective in reducing dangerous driving, say cycling advocates, including Paul Steely White, Executive Director of Transportation Alternatives.

RELATED: How Bikes Won in NYC

Earlier this year the city announced it planned to complete protected bike lane projects in all five boroughs in 2016, as well as add 50 more miles of bike lanes, including 15 miles with some form of protection. The result of this investment in biking? Across the city, ridership increased by 83 percent between 2010 and 2014, according to a recent report from the NYDOT. Additionally, data from Citi Bike, the country’s largest and most popular bike-share system, shows that in Midtown bicycle speeds now outpace cabs by 2 mph.

But, says Steely White, to reach the city’s goal of zero traffic deaths by 2024, New York must do more. In April, NYC’s City Council called for an additional $300 million in annual funding for transportation safety projects, but the mayor’s office has, so far, failed to act on the proposal.

Local Advice

Brooklyn by Bike combines two of New York’s most esteemed activities, bike riding and eating. Join the group for one of their moderately priced rides, including a Tour de Donut, Tour de Pupusa, and Dumpling Tour.

5: Seattle

When we last ranked this city in 2014, a grassroots movement, the Seattle Neighborhood Greenways, had helped spawn widespread support for increased bicycle infrastructure and bicycle safety measures. The city had unveiled a progressive new master plan for biking, and a new transportation levy that would allot nearly a billion dollars over nine years for bicycle and pedestrian improvements was on the ballot.

The Move Seattle levy faced opposition from well-heeled and prominent forces. Businesswoman Faye Garneau spent $325,000 of her own money attacking bicycle transportation. And editorials in the Seattle Times argued for expensive fixes to roads and freeways that would prioritize motorized traffic. But, in the fall of 2015, the levy passed with 57 percent of the vote. Tom Fucoloro of the Seattle Bike Blog says the city now has the money, and “a mandate,” to implement the bicycle master plan’s proposed 50-mile network of protected bikeways and 60 miles of neighborhood greenways, which prioritize bikes.

RELATED: Why Seattle Is Still a Cyclist's Dream City

In 2014, Seattle hired Chicago’s former DOT head, Scott Kubly, and put planner Nicole Freedman, a former Olympic racer who’d previously served as Boston’s bike coordinator, in charge of the bike program. Within months of Kubly’s arrival in Seattle, the city completed a protected bike lane on downtown’s Second Avenue, as an example of the infrastructure to come, and orchestrated a $1.4 million buyout of the privately owned and struggling bikeshare system, Pronto. The project has had its setbacks: Kubly paid a $5,000 fine for not filing a waiver to allow him to work with a previous employer—he’d served as president of Alta Bicycle Share (now called Motivate), which operates Pronto—and Freedman left Seattle in September to become transportation director for the city of Newton, Massachusetts. But the city continues to be making efforts to boost Pronto’s waning ridership. It’s seeking to dramatically expand the the number of stations and add as many as 2,500 bikes, including some electric-assist models, to the system—an innovative solution to flatten the notoriously hilly city.

Local Advice

Looking to go car-free (or car-light)? G&O; Family Cyclery caters to the vehicle-less lifestyle, with a wide assortment of cargo bikes, folding bikes, and more. In March, when a gas explosion destroyed the store (no one was hurt), customers raised more than $45,000 to help the owners rebuild.

6: Minneapolis

Minneapolis’s success as a beacon of bike friendliness is largely owed to decisions made decades ago. In the 90s and 2000s, the abandoned railways of this former industrial city were transformed into the spine of an expansive bike path network that now funnels thousands of riders across town and into to the city center.

Today, a vibrant bike culture swirls around one of the nation’s highest rates of urban cycling, with bike commutes comprising nearly 5 percent of all work trips. Last year, Minneapolis’s open streets festivals drew 65,000 people to revel on motor vehicle-free roadways. And a city-run Safe Routes to School program has resulted in increased student commuting at schools like South High, where hundreds of kids now arrive by bike.

In recent years, Minneapolis has complemented its trail system with forty miles of bicycle boulevards that usher riders through quiet neighborhood streets, and a bike share system, Nice Ride, that offers more bikes per resident than any other major city in the U.S. But perhaps the city’s greatest cycling-related accomplishment looms on the near horizon. In July of 2015, the City Council approved a 30-mile network of protected bike lanes, and allocated robust funding to the project. Already, three major downtown corridors—Washington Ave., Hennepin Ave. and 3rd Street—are either completed, under construction, or slated to receive protected bike lanes by 2020.

Local Advice

In Minneapolis—where bike riders say, “ice, schmice”—the annual Winter Bike Expo offers fat bike demos, seminars on cold weather riding, and a nighttime crit, all conveniently located on the Midtown Greenway bike trail. – Danielle Zickl

7: Austin, Texas

Over the last two years, Austin has unveiled a number of multimillion dollar public works projects: the iconic Boardwalk that hovers over the Colorado River and became an instant tourist attraction; the 7-mile Walnut Creek Trail that links east Austin with low-income housing, urban farms, and the famed Driveway Series weekly bike race; and a soon-to-be-unveiled bike-ped bridge spanning the 800-plus acre Barton Creek Greenbelt, giving local riders a safe and serene route where they once, literally, had to ride on a freeway.

But while those projects have garnered fanfare and ribbon cutting ceremonies, planners in Austin’s transportation department have quietly upgraded the city’s on-street bike infrastructure at every opportunity. Recent repaving projects resulted in nearly 10 miles of protected bike lanes, connecting children with schools and senior citizens to parks, and giving bike-riding professionals safe passage through the heart of the city. More than 10 percent of Austinites who live within an 8 square-mile area around downtown now commute by bike.

But despite the progress, fully funding the bicycle/urban trail master plan and improving safety remain priorities, says Mercedes Feris, executive director of Bike Austin. For example, after a city council member fought the installation of dedicated bike lanes on Mesa Drive in west Austin, a young boy was struck while riding his bike. A forthcoming Vision Zero policy should give the transportation department greater ability to implement safety-based projects where it encounters community pushback. And a transportation bond on the November ballot allots $50 million to new trails and bike lanes.

Local Advice

With spring, summer, and fall temps that regularly hit 100-plus degrees, the best rides end at a local swimming hole. Hit McKinney Falls State Park for five miles of flowing kid- and cyclocross-bike-friendly trails, then soak in one of the park’s two waterfall-fed pools.

8: Cambridge, Massachusetts

In 2015, the national advocacy group People for Bikes named Cambridge’s recently completed protected bike lane on Western Avenue the most impressive such project in the entire country. But city planners may have been too busy drafting the next phase of transformative bike infrastructure to notice. In developing its new master plan for cycling, the city deployed “street teams” to meet non-bike riding residents in the places they live, work, shop, and exercise. Overwhelmingly, locals asked for more facilities just like Western Avenue. In fact, two-thirds of respondents stated that implementing more protected lanes was, “very important.”

Cambridge already ranks as one of the safest and most progressive cities for cycling, thanks in large part to air-quality policies implemented in the late-’90s. Cambridge’s Parking and Transportation Demand Management Ordinance requires new development projects to reduce single occupancy vehicle trips, and to help promote bike riding with high quality bicycle parking, on-site showers, and even roadway redesign. Today, forty four-percent of all bike commuters are female (an indicator of how safe cycling feels in a city), the highest percentage of the top ten cities in our survey. And, though crashes do occur, fatalities are rare, thanks to narrow streets, traffic-calming measures, and the resulting low vehicle speeds. In 2014, after a cyclist was sideswiped by a garbage truck, the city installed sideguards on all of its large vehicles.

In Kendall Square, where a permanent bike counter records nearly half a million trips annually, the city held a design contest to address bike parking. The winning bike rack, the Flycycle, was created collaboratively by an architect and a designer, and combines elegance with efficiency. One of the winning applicants’ greatest challenges? Meeting the city’s strict regulations on proper bike parking structures.

Local Advice

Join one of the Cambridge Bicycle Committee’s biannual community rides, which highlight the city’s history and culture, and are escorted by Cambridge’s bike-mounted police officers. Previous ride themes have included “Don’t bike like my brother,” in honor of Cambridge born-and-raised Car Talk host Tom Magliozzi, as well as the “Sweet Ride,” in which riders were treated to a tour of Cambridge’s candy manufacturing history (15 million Junior Mints are still produced daily on Main Street), and fed specially printed NECCO heart candies.

9: Washington, DC

Our nation’s capital has long led the country in urban cycling. DC implemented one of the country’s first widespread bike share programs, Capital Bikeshare (which will expand by 99 stations by 2018). The city was one of the first to begin transforming its protected bike lanes into permanent transportation features with concrete curbs blockading cars from bicycles—including the city’s new First Street bike lane connecting Union Station and the Metropolitan Branch Trail. And, in 2015, DC set a new standard for developing future generations of confident bike riders by instituting compulsory classes on bicycle riding, safety, and maintenance for every second grader in the city’s public schools.

The program, funded by the DC Department of Transportation and private donors, uses a fleet of nearly 1,000 Diamondback Mini-Viper BMX bikes that rotate through DC elementary schools. The physical education curriculum begins with teaching kids how to balance, pedal, and steer at the same time, and culminates with an off-campus ride aimed at engaging the local community. Imagining the impact of the program, and its potential effect on ridership and bike infrastructure in DC, “gives me goose bumps,” says Gregory Billing, executive director of the Washington Area Bicyclist Association.

RELATED: How to Bike Washington, D.C.

Inequities in the quality of bike infrastructure and level of ridership remain between the western and eastern halves of DC. But the long-awaited Anacostia Riverwalk Trail Extension will soon complete a 70-mile off-street path system running from the University of Maryland to Nationals Park, while two multimillion dollar projects—the 11th Street and Frederick Douglas bridges—include expansive bike paths.

Local Advice

The second annual DC Bike Ride in May of 2017 will open 17 miles of car-free streets and culminate with a post-ride party on Pennsylvania Avenue, near the U.S. Capitol. In 2016, DJ Questlove rocked the ride.

10: Boulder, Colorado

Here’s proof that even Boulder—long-considered a pillar of bike friendliness, where nearly 9 percent of residents commute by bike—can feel the effects of bikelash. In July 2015, the city reduced Folsom Street, an arterial that connects the University of Colorado Boulder campus with neighborhoods and businesses, from four lanes to two and installed protected bike lanes along the length of the corridor. Advocates applauded the effort, part of the city’s “Living Labs” project, a transportation initiative aimed at installing more modern infrastructure that’s statistically proven to save lives and reduce vehicle and pedestrian crashes over time. But after just 11 weeks, and lots of outraged letters from drivers whose commute times increased by several minutes, Boulder removed the bike lanes.

“The whole episode caused the department of transportation to retreat, and the city indicated that they will require extremely extensive review and data collection on future projects,” says Sue Prant, executive director of the advocacy organization Community Cycles. “There’s been no movement from the city on protected bike lanes, since.”

RELATED: How to Ride Boulder

The removal of the Folsom Street protected bike lanes, especially in Boulder, a long-time national leader in bike-friendliness, certainly sends a discouraging message. But cities such as Boulder, where traffic is generally sparse and parking is often free, face different motivations and challenges in promoting urban cycling. Reducing climate change and increasing public health top the objectives of the city’s Living Labs project. So while the episode caused Boulder to drop in this year’s survey, we appreciate the effort.

Local Advice

Pedaling Minds, a Boulder-based after school program for elementary age kids, is run by former pro bike racer and Olympian Mike Friedman. In addition to fundamental bike safety and skills instruction, the program uses bikes to teach scientific principles—for example, exploring the gyroscopic effect of a wheel.

11: Denver

Come, pedal through Denver’s developing downtown protected bike lane network: We begin on 15th Street, riding one of Denver’s 700 B-cycle bikes, beside associate city planner Rachael Bronson. As we ride, Bronson explains the city’s focus, to first build out a protected biking network in its core, “where we see the largest concentration of ridership.” This protected bike lane along 15th Street, demarcated by plastic posts and paint, was the city’s first, and says Bronson, “we’ve learned a lot.” The left side alignment (to avoid bus stops) makes for awkward side street transitions, and construction crews often block the lane. A few blocks over, riding down Lawrence Street, we see lessons learned: floating concrete islands that mitigate bus and bike conflicts.

Because, according to local advocates, the mayor has yet to fully embrace equitable transportation for all residents in his annual budget—Bronson and her colleagues continue to work with temporary paint and plastic posts in addition to more permanent structures. But what they’ve accomplished impresses. We ride a portion of Denver’s 100-plus mile trail system, following Cherry Creek to its confluence at the Platte River—past a summer camp of cycling children, and across the stunning Highland bicycle bridge (at another, the Millennium Bridge, we must dismount and push our bikes up a set of stairs).

We return to the B-cycle dock along Arapahoe, where a parking protected bike lane places us closer to the curb, away from heavy traffic. Bronson says the city plans to experiment with concrete curbs and planters to physically separate motor vehicles and bike riders. Since 2011, says Piep van Heuven of Bicycle Colorado, Denver has completed about a third of the projects in its recently updated $120 million master plan for bicycle transportation—and the work that remains ahead will also be the hardest and most expensive.

Local Advice

Denver’s new Ruby Hill bike park, a $1.7 million renovation of 7 acres of little-used park space, includes a 2-mile trail, slopestyle dirt jumps and curved wooden ramps, and panoramic views of the Rocky Mountains. “It’s one of the nicest bike parks in the country,” says van Hueven.

12: Fort Collins, Colorado

In 2014, Fort Collins unveiled a plan to improve upon an extensive but increasingly outdated network of bike lanes and paths. The proposed low-stress network—the goal of which is to increase the number of bicycle commuters from the existing 6.2 percent to 20 percent by the year 2020—has already made headway. The newly created Remington Greenway brought buffered bike lanes to a 1.7-mile corridor that connects the city’s Old Town with the cross-town Spring Creek Trail. And local business owners, in welcoming an increase in foot and bicycle traffic, applauded the removal of car parking spots to create a dedicated space for bikes on Mason Street, which borders the Colorado State University campus.

RELATED: Why It's Time to Get Into Bike Commuting

The city offers over a half dozen different bike education classes, ranging from cycling with children to a class that teaches adult women how to ride bikes. Fort Collins’s most popular curriculum is its Bicycle Friendly Driver Certification Course, which was created in 2015 and teaches people how to safely operate motor vehicles near bicycle riders. Fort Collins’ bicycle program manager, Tessa Greegor, credits the bike-friendly driver program’s success to its wider audience—the course appeals to people who both drive and bike—and the city encourages businesses that employ professional drivers to promote the free course.

Fort Collins is cautiously wading forward on implementing the protected bike lanes called for in the city’s low-stress bike network plan, says advocate Chris Johnson, Executive Director of Bike Fort Collins. “We’re very much paying attention to what happened in Boulder, where the rollout didn’t go as planned,” he says. Only one mile of protected bike lane exists in Fort Collins so far, a pilot project connecting the aforementioned Mason Street and Remington corridors.

Local Advice

Tune into 88.9 FM KRFC on Wednesdays from 6 to 7 p.m. for a radio show devoted entirely to bikes and beer.

13: Indianapolis

In 2013, upon the completion of Indianapolis’s $63 million Cultural Trail, an 8-mile off-street biking/walking path near the city’s core, a major question remained: Would the hefty investment of federal grants and privately donated funds pay off? The answer, unequivocally, is yes. A 2015 report by the Indiana University Public Policy Institute showed property values within 500 feet of the artfully implemented protected bike lanes rose 148 percent between 2008 (when the first section of the Cultural Trail opened) and 2014. The subsequent increase in assessed property value totaled more than $1 billion. Also, about half of the business owners along the corridor reported an increase in both the number of customers and annual revenue.

Following the Cultural Trail’s success, in 2014 Indianapolis implemented the Indiana Pacers Bikeshare program (thanks to a contribution by the local NBA team’s owner). With just 250 bikes in its rotation, locals and visitors logged an impressive 107,000 annual rides in the system’s first year. The on-street infrastructure progress continues, as well. This year Indianapolis aims to add three new protected bike lanes bisecting downtown.

Current US Census data doesn’t capture Indianapolis’s recent investment in bike riding, but Oran Sands, vice president of operations for the advocacy group IndyCog, says that bike commuting grew 42 percent from 2014 to 2015. A pilot program from the Federal Highway Administration will bring automated bike counters to Indy.

The man responsible for much of Indianapolis’s transformation, Mayor Greg Ballard, no longer holds office, but the city’s new mayor, Joe Hogsett, similarly supports bike riding—albeit with a modern flourish. “He doesn’t identify as a ‘cyclist,’” says Kevin Whited, IndyCog's former executive director. “But he rides to work at least once a week.”

Local Advice

The city’s annual N.I.T.E Ride (Navigate Indy This Evening) begins well before the sun sets. Start your day with Central Indiana Bicycling Association’s morning Club Ride, with 16- to 60-mile routes starting at the Major Taylor Velodrome. Then participate in the LITE Up Your Bike contest for a chance at winning a $100 gift card from Bicycle Garage Indy. The main event starts at 11 p.m. with a roughly 15- to 19-mile ride through downtown.

14: Salt Lake City

Over the last two years, Salt Lake City distinguished itself as one of the nation’s most progressive cities for cycling. In 2014, the city installed two glistening bike lanes that are protected by concrete curbs and guide cyclists through downtown. Then, it garnered national attention by connecting the new bike lanes with one of the country’s first protected intersections, which uses bike-specific signaling and concrete barriers to minimize conflicts between cyclists and drivers. Almost immediately, the bike lanes resulted in increased sales for nearby business, 50 percent fewer crashes, and helped the city garner one of the highest rates of bike-share use in the country.

As part of a broader plan to provide a low-stress bikeway within a half mile of every resident, Salt Lake City also recently completed (or is in the process of completing) three new bicycle boulevard projects, with 25mph speed limits, traffic diverters, and bicycle signals to usher riders across intersections. But this idyllic locale for recreational riding also understands the desires of more confident and faster riders. The bicycle master plan recognizes the need for “dual-purpose facilities” on road projects—i.e., striping bike lanes on roads where a side-path is already present.

RELATED: Why Cyclists Thrive in Salt Lake

Local advocates, like Phil Sarnoff, the Executive Director of Bike Utah, credit much of the city’s progress to former mayor Ralph Becker. “You couldn’t ask for a better mayor when it comes to supporting bicycling,” says Sarnoff. However, Becker’s replacement, Jackie Biskupski, criticized the city’s new protected bike lanes during her campaign—a concern if Salt Lake City aims to continue its progress.

Local Advice

Take a ride down Salt Lake’s 9-Line Trail, a key crosstown connection that features a BMX pump track and bike-themed art created by local students with the school group Latinos in Action.

15: Philadelphia

In the last two years, a pair of long-awaited projects significantly upgraded Philadelphia’s Schuylkill River—the backbone of this city’s bike network. The 15-foot wide Schuylkill Banks Boardwalk hovers over the water for 2,000 feet, bypassing an active rail line. Since its unveiling in 2014, the Boardwalk has become one of the city’s most Instagrammed amenities, providing spectacular views of the city’s skyline and creating a critical connection between the University of Pennsylvania and downtown. Further north on the Schuylkill River Trail, the soaring stone arches of the Manayunk Bridge were repurposed in 2015 as a bicycle and pedestrian thoroughfare, linking residents with the waterfront.

The city recently received $300,000 in grant funding to begin implementation of Mayor Jim Kenney’s proposed 30-mile network of protected bike lanes. And, in April of 2015, the Indego bike share system brought 1,000 bikes to central Philadelphia. Philadelphia aims to cover the entire city within the next two to three years and, in collaboration with the Better Bike Share Partnership and the Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia, has placed 30 percent of bike share stations in low-income and underserved communities—an important equity initiative for Philadelphia, which has the highest rate of deep poverty of the 10 largest US cities.

Though Philadelphia lacks a Vision Zero policy, a new safety program uses funds from red light cameras to paint new bike lanes and enhance existing ones.

Local Advice

At the Kensington Kinetic Sculpture Derby and Arts Festival, held each May, you can watch from the sidelines as pedal-powered floats take on obstacles such as the foamy “bubble alley” or the finish-line mud pit—or, try to craft your own outlandish machine.

16: Madison, Wisconsin

Madison and surrounding Dane County have continued to upgrade an expansive off-street trail network. In 2017, the completion of a missing one-mile segment of the Capital City State Trail will allow residents to ride entirely on trails from Madison to Milwaukee, 80 miles to the east. And, just south of Madison, the 2.5-mile Capital City State Trail extension will connect two nearby parks and include a mile-long bridge and boardwalk across Lake Waubesa (the longest bicycle bridge ever built in Wisconsin).

The city’s bike culture also thrives, buoyed in large part by the support of nearby bike brands such as Trek Bicycles, which owns (and heavily subsidizes) the city’s B-cycle bike share system. During Madison’s bike month, Planet Bike hosts Bacon on the Bike Path, while Saris offers commuters bratcakes, a fresh-from the grill sausage wrapped in a warm pancake and drizzled with syrup.

The nation’s leading bike advocacy group, the League of American Bicyclists, recently upgraded Madison to Platinum status in 2015, the organization’s highest community ranking. However, Madison still lacks much of the progressive and modern infrastructure statistically proven to make all road users safer—it has just one protected bike lane—and encourage so-called “interested but concerned” cyclists to ride more.

Local Advice

The Capital Brewery Bike Club combines two things often beloved by bicyclists: stunning scenery and delicious beer. Take in Madison’s rolling green hills and winding farm lanes on club routes aptly named after each of the brewery’s offerings, then enjoy a post-ride IPA. The hoppy Grateful Red may have you singing along to “Scarlet Begonias” within a few sips.

17: Boston

“The car is no longer king,” former Boston mayor Tom Menino, who oversaw the city for more than two decades, once famously declared. Under Menino’s reign, Boston transformed itself from this magazine’s perennial Worst City for Cycling designation to amongst the best cities for bicycling in the country. With its robust New Balance Hubway bike share system (one of the largest per capita with nearly 2,000 bikes), Boston experienced a 35 percent increase in Census-counted bicycle commuters between 2010 and 2014.

RELATED: Why Mayors Love Bike Lanes

But after Menino died of cancer in 2014, and tireless city bicycle director Nicole Freedman left to take a job with Seattle’s transportation department in 2015 (she’s now back in Massachusetts, as transportation director in nearby Newton), local bicycle advocates were frustrated by the slow progress of bike infrastructure. “Currently, the interests of free parking often trump the interests of safety,” says Becca Wolfson, executive director of the Boston Cyclists Union.

Though Boston’s seen little physical progress over the last two years, potentially revolutionary projects are in the works. In 2017, the city will unveil the initial legs of Connect Historic Boston, a $23 million network of protected bike lanes encircling Boston’s central business district and North End, which was funded by federal and city money and support from the national advocacy organization People for Bikes. In March 2015, the new administration committed to the redesign of Commonwealth Avenue, the street that accounts for the highest number of cyclist doorings in Boston. When construction is complete in a few years it will have a protected bike lane and protected intersections, says Wolfson.

Local Advice

Compete in state advocacy group MassBike’s Rush Hour Challenge, a race that pits pedestrians, bikes, cars, and transit against each other between downtown Boston and neighboring Somerville’s Davis Square, with bragging rights—and an awareness of the challenges facing all modes of travel—at stake. An after-party at Redbones BBQ benefits MassBike and the New England Mountain Biking Association. In 2016, an electric-assist bike took first place.

18: Eugene, Oregon

In 2016, Eugene unveiled a new 20-year transportation plan that aims to update much of the city’s outdated bicycle infrastructure, and implement an extensive low-stress bike network of protected bike lanes and greenways. The document calls for prioritizing active transportation, and tripling the percentage of people walking and biking, in a city that's already one of the nation’s top locales for bike commuting, with 6.8 percent of residents riding to work.

But locals won’t have to wait for the plan’s approval to experience the new wave of bike amenities. Over the last three years Eugene has been widening and adding buffers to the web of rudimentary bike lanes it first painted in the 1970s. Three soon-to-be-completed bicycle-pedestrian bridges will connect nearby neighborhoods and commercial areas to the seven-mile Fern Ridge Path system. And, after years of planning, public debate—and finally—construction, one of the city’s primary thoroughfares, South Willamette Street, was reduced from four lanes to two, with bike lanes added to either side of the roadway. The city recently created a task force to study a formal Vision Zero policy, and in 2017, Eugene will launch a bike-share system in collaboration with the University of Oregon.

Local Advice

Al Hongo, the founder of Eugene’s Moonlight Mash social ride, says the event “rose from the ashes of my 1987 Honda Accord.” He removed the stereo system, mounted it to a cargo bike, and began leading a music-infused ride in the light of the full moon. Today, the Mash draws hundreds of riders and its playlist is broadcast live by the University of Oregon’s student-run radio station.

19: New Orleans

“There’s lots of momentum, and we’re headed in the right direction,” says Dan Favre, the Executive Director of New Orleans advocacy group Bike Easy. As New Orleans rebuilt its roadways and green spaces following Hurricane Katrina, the city renewed its commitment to bike riding. In 2015, New Orleans opened the $9.1 million Lafitte Greenway, a 2.6-mile linear park connecting the French Quarter with City Park, and surpassed 100 total miles of bikeways the next year (though nearly half are shared lane markings). Residents have responded. According to current U.S. Census data, the number of bike commuters increased by 56 percent between 2010 and 2014, putting New Orleans among the top 20 U.S. cities in daily bike riding.

Local enthusiasm for cycling is evident nearly every night of the week, with social rides rolling through the streets of New Orleans. Take Tuesday evening’s Get Up and Ride, a festive event that can draw as many as 800 riders, their bikes colorfully adorned with LEDs. “Get Up and Ride is a primarily African-American group, many of whom haven’t ridden bikes in years,” says Favre. “There’s this perception that all the new bike riders in New Orleans are young white people, and that’s not accurate.”

Still, says Favre, despite the momentum, every new bike lane project can be a struggle. It still feels like the city's complete streets policy is optional. And when bringing new road projects to residents and communities—like a road diet and bike lane project on Canal Boulevard, a segment of the city lacking bike infrastructure—the city sometimes fails to effectively explain the benefits of new bicycle lanes (such as safety for all road users).

Local Advice

Join a Free Wheelin’ Bike Tour for a historic ride around New Orleans. You’ll spin below moss-draped oaks, past Antebellum mansions and ghost-inhabited cemeteries, and break for rich chicory-flavored coffee and powdered sugar-coated beignets. Or, check out NOLA Social Ride’s online calendar, where weekly events range from the It’s “All About The Music” Bike Ride, to the Happy Thursday ride.

20: Pittsburgh

Since 2000, Pittsburgh ranks only second to Detroit, Michigan in the number of new bike commuters on its streets, according to data compiled by the League of American Bicyclists from the US Census. Over the span of 14 years, the city saw a whopping 361 percent increase in ridership.

A new bike-share system with 50 stations and 500 bikes was unveiled in July of 2015, and racked up 12,000 trips per month. In 2014, in partnership with the Green Lane Project, an initiative of the national advocacy organization People for Bikes, the city installed three protected bike lanes, including a cycletrack on Penn Avenue that funnels riders from the Strip District to Downtown and required changing the road to a one-way traffic pattern. When critics argued the new Penn Avenue bike lane saw little ridership, the Pittsburgh Downtown Partnership, which supported the lane, released numbers from an automated counter showing that the bike lane saw 24,000 trips in a single month.

The city’s three Open Streets events draw as many as 55,000 people to revel in motor vehicle-free roadways. And, Pittsburgh’s week-and-a-half-long Bike Fest includes about 75 events to celebrate cycling.

Local advocates have lamented that the number of new bike lanes has slowed, but they hope the city’s new bike plan will bring fresh projects and better funding.

Local Advice

Rip the 43 miles of singletrack and freeride skills area situated in North Park, an Allegheny County greenspace 13 miles north of Pittsburgh. Then, dig into a plate of Big Ring onion rings and quaff a local Helltown Hefeweizen at the Over the Bar Bicycle Café, located in the park’s former boathouse.

21: Oakland, California

Up until 2015, Oakland operated without a unified transportation department. However, after integrating its various transportation agencies—from planning, to public works, to the city’s bicycle and pedestrian program—Oakland has made big strides in bike friendliness.

In May, Oakland inaugurated its first protected bike lane on Telegraph Avenue—part of a redesign and road diet on a corridor that serves as the cultural heart of the city. The forthcoming expansion of the regional Bay Area Bike Share system will bring 850 bikes to Oakland, with 20 percent of the stations being placed in low-income neighborhoods. And, the Lake Merritt BART Bikeways project, expected to be completed this year, will bring 36 blocks of buffered bike lanes to Oakland’s downtown. To document all of the DOTs completed and upcoming work, the city publishes an I Bike Oakland newsletter in four languages.

The effect of Oakland’s expanding bike network is evidenced by its ridership. The rate of Census-counted bike commuters increased by 53 percent (to 3.7 percent of all trips) between 2010 and 2014.

Local Advice

Women who’re interested or new to cycling can link up with the advocacy group Walk Oakland Bike Oakland for a three-part women’s cycling workshop called Ride Like a Girl, which focuses on commuting basics, gear selection, and fitness. WOBO also hosts a Women Bike Happy Hour on the fourth Thursday of each month to foster off-bike socializing, because, jokes WOBO board president Chris Hwang, “We like to drink, too”

22: Tempe, Arizona

Much of the support for urban cycling in Tempe swirls around the city’s active and enthusiastic advocacy organization, the Tempe Bicycle Action Group (a.k.a. TBAG). The group hosts weekly and annual cycling events—such as its Summer Solstice Ride, a cross-city tour that visits various water fountains and pools, and partakes in competitive slip and slide—and also regularly rallies local bike riders to support and critique Tempe’s cycling initiatives. As part of a new transportation plan, the city has been adding high-quality bike infrastructure with increasing regularity—though, not without pushback, and a handful of missteps.

When Tempe reduced the arterial McClintock Drive from five lanes to four, and added buffered bike lanes protected by plastic bollards, bike riders cheered. But after drivers regularly ran into the bollards, the city removed the physical protection. In another effort to increase cyclist safety and comfort, Tempe experimented with stamped pavement on a street redesign, creating a rumble strip to alert drifting cars. But pavement was stamped within the bike lane, reducing its width to just 2.5 feet of rideable space.

Despite the experimental errors, Tempe clearly aims to make cycling safer and more enjoyable. Many new road redesigns include a public art installation, such as a work dubbed “In Bloom,” a metal sculpture with golden flowers on the city’s first, half-mile-long protected bike lane.

Local Advice

Give back and have a blast at Tempe’s Tour de Fat stop, where beer drinkers and bike riders raise as much as $100,000 for local cycling charities. Or, enter Cranksgiving Tempe, a food drive and scavenger hunt by bike—that fed 1,900 people in 2015.

23: Tucson, Arizona

A longtime haven for avid recreational cyclists and racers, Tucson boasts hundreds of miles of single-striped bike lanes and paved paths, including the 100-mile Loop trail network that rings the city. The iconic 27-mile climb up Mount Lemmon resides just outside Tucson’s city limits and hundreds of cyclists gather on Saturday mornings for the city’s infamous Shootout ride. But when it came to the needs of bike commuters and families, many residents found Tucson’s bike network inadequate.

Enter Living Streets Alliance, a grassroots organization formed in 2011—and composed of urban planners, educators, moms, and dads—that’s using outreach and advocacy to transform Tucson’s streets to accommodate all levels of bike riders. During the last year alone, LSA drew 55,000 people to their open streets events, worked with 16,000 kids from 52 schools via the Safe Routes to School program, and encouraged employees from 77 businesses to log more than 27,000 miles in a commuter challenge. Perhaps most impressively, though, LSA helped see the city through the implementation of a protected bike lane in its downtown core.

RELATED: On Your Mark, Get Set, Go: Where to Ride in Tucson

With support from the LSA, in July Tucson unveiled a Bicycle Boulevard Master Plan that calls for a 193-mile network of bicycle boulevards that will put nearly half of all residents within a quarter-mile of a low-stress bikeway. In combination with a new bike-share program, launching in 2017, all forms of bike riding in Tucson should continue to thrive.

Local Advice

For more than 25 years, Bicycle Inter Community Art & Salvage (or, BICAS) has served as Tucson’s most diverse cycling resource. More than just a community bike shop, in addition to open shop hours and build-a-bike programs, events at BICAS range from bikepacking seminars to workshops from local artists.

24: Los Angeles

After years of planning, community outreach, and legal challenges, Los Angeles’s most iconic road project, My Figueroa, will finally break ground this fall. The heavily used three-mile corridor will transform an eight-lane urban highway into a multi-modal street with protected bike lanes and bike specific signage—and connect the University of Southern California, parks, and museums with downtown LA. The effort, part of the Mayor’s “Great Streets” initiative, symbolizes a shift in transportation ideology for this city.

But the victory didn’t come without a fight. “Cycling in Los Angeles is a work in progress, sometimes slower progress than we’d like,” says Tamika L. Butler, Executive Director of the Los Angeles County Bicycle Coalition. “People are so concerned with their commutes. They don’t want to lose their car lanes. But this isn’t about commutes, this is about communities.”

A new bike share system, Bike Metro, recently brought 65 stations to LA’s core, and across the 469-square-mile city, a handful of road diets and protected bike lanes have helped to steadily increase cycling’s mode share. Although progress remains slow and piecemeal, Butler says, "there is an excitement in the city, elected officials and agency heads that care, and phenomenal advocates." A proposed half-cent transportation sales tax (“though sales taxes are regressive,” says Butler) could boost LA’s bike network.

Local Advice

Two LA-area charity rides offer very different versions of the city’s cycling terrain. Phil Gaimon’s Malibu Gran Cookie Dough tackles the mountain canyons rising from the Pacific Coast Highway, with the toughest “Double Fudge” route gaining more than 12,000 feet in elevation over 117 miles. Cookies greet riders at the top of each climb, and the ride benefits City of Hope and Fireflies West. On the other end of the spectrum, the Los Angeles River Ride starts in central LA’s Griffith Park, traverses 100 mostly flat miles (round-trip) to Long Beach and back, and benefits the Los Angeles County Bicycle Coalition.

25: Arlington, Virginia

The Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority’s Safe Track program, a yearlong maintenance project that involves rolling closures and reduced hours on the region’s Metro lines, has been a boon for biking in Arlington. “Safe Track has allowed us to experiment with different ideas to get people on bikes,” says Gillian Burgess, chair of Arlington’s bicycle advisory committee. Some of the successful initiatives include a two-dollar, one-way fare for Capital Bike Share rides, improved signage on the network of trails that funnels commuters from Arlington across the Potomac, and pop-up protected bike lanes to help educate residents about the kind of bike infrastructure that might make them choose cycling over transit more often.

One of the most effective ways of increasing ridership, says Burgess, has been getting experienced commuters to offer help to others in their neighborhood who are interested in riding. “Just sending a note on your neighborhood listserv, saying you commute regularly and are happy to help anyone else navigate their way downtown, or get air in their bike tires, has a big impact,” says Burgess.

Outside its encouragement programs, Arlington continues to upgrade its bike network at a consistent pace. After installing its first protected bike lane as a pilot project in 2014, says Burgess, “the County has committed to considering such infrastructure for all future repaving projects.” But, as in many cities, consistent enforcement remains an issue.

Local Advice

A resource for cyclists young and old, Phoenix Bikes’s youth and community programs educate all comers on bike maintenance and safety. The shop says it offers the largest selection of used bikes and bike parts in the DC area, has women's events and weekly youth rides, and sponsors a local racing team.

26: San Jose, California

As the heart of Silicon Valley, and its forward-thinking tech-based economy, the origins of San Jose’s road system remain decidedly old school. Wide and fast arterial roads ring the city, and major freeways bisect its neighborhoods like rushing rivers. However, in recent years San Jose’s leaders have determined to change the city’s gas guzzling nature. In 2015, San Jose striped 35 miles of enhanced bike lanes, with wide buffers separating bike riders from vehicles, and added green paint to highlight conflict zones at 117 intersections.

On roadway reconstruction projects, reducing vehicle travel lanes to calm traffic and make space for bikes has become the norm. In one instance, on the main thoroughfare running through the tight-knit and charming community of Willow Glen, city officials withstood criticism and contention over a road diet that added bike lanes—and used data showing relatively similar travel speeds and fewer crashes to win over critics. “More studies were done on that quarter-mile long road project than probably any other in city history,” says Colin Heyne, deputy director for the Silicon Valley Bicycle Coalition.

However, much work remains, primarily on the equity front. An analysis of crash data as part of a Vision Zero safety initiative showed 50 percent of San Jose’s fatal or major injury-causing crashes occur on just 3 percent of its roadways—those big and fast arterial streets, primarily in low-income neighborhoods.

Local Advice

The bike-party phenomenon (read: social, inclusive, and celebratory cycling) has swept the country—but it all started in San Jose, and the original bike party still rocks. Ride themes range from an Independence Ride (wear red, white, and blue), to a Purple Formal Ride (your finest purple attire, in honor of Prince, of course), to a rolling dance party with a wirelessly synced DJ.

27: Boise, Idaho

Boise, Idaho has a problem: Facing a growing urban population that increasingly desires to live and work in its downtown area, the city has long sought to create safe and effective protected bike lanes on the major roadways running through its urban core. But the city does not actually own the roads on which it wants to build these bike lanes—surrounding Ada County Highway District controls the roads.

In 2014, in line with a bicycle master plan the county approved in 2009, buffered bike lanes protected with plastic bollards were installed on two downtown corridors. As often happens when new forms of infrastructure are introduced, opinions became heated. And after just five weeks, though travel times hadn’t increased significantly, the ACHD removed the bike lanes. Boise planners and city officials haven’t relented, and still hope to create a protected bike lane network in the center of the city—but opposition from the public and area businesses remains.

RELATED: Boise Goes Bike-Friendly

The battle over Boise’s roads shouldn’t, however, detract from the vibrancy of the city’s bike community, and the passion of its cycling advocates. Boise’s Tour de Fat stop draws over 10,000 revelers, and the city’s Pedal 4 the People festival is a 10-day long celebration of all things bike. In collaboration with a community shop, Boise Bicycle Project, a nearby women’s prison began a program called Shifting Gears, in which inmates repair bicycles for children, and then earn a voucher for a bike of their own upon release.

Local Advice

The Mad Max-themed Helladrome event during Boise’s Pedal for the People festival pits adults and kids (and adults riding kids bikes) against each other on an obstacle course in an abandoned parking lot. Push-ups, libations, and laughs ensue.

28: Long Beach, California

Long Beach has long touted its bike friendliness: Protected bike lanes, installed in 2011, that run the length of the city’s downtown, resulted in a 38 percent increase in bike riders, a 25 percent reduction in bicycle and vehicle crashes, and a number of new businesses along the corridors. In March of 2015, a new bike share introduced 32 of 50 stations and 300 of 500 new bikes to the city, and is expected to be a hit particularly near California State University–Long Beach. The city runs a Safe Routes to School program and says that 30,000 elementary school students now walk or bike to school (that’s nearly 60 percent of elementary and middle school students, one of the nation’s highest rates).

But, according to local advocates like Danny Gamboa, who runs the Bike Uptown community bike shop and conducts bicycle safety classes on behalf of the city, bicycle equity remains an issue in Long Beach. “Much of the city’s efforts have followed the path of least resistance,” says Gamboa, with new projects being implemented in primarily white and affluent areas.

The recently formed advocacy group, Walk Bike Long Beach, aims to guide the city’s forthcoming update to the Bicycle Master Plan and create a more equitable bike network. The organization’s efforts are already paying off. “The city is building a nearly 10-mile-long bicycle boulevard through north Long Beach, a community of color,” says Gamboa, and in 2016, Long Beach installed one mile of two protected bike lanes along Artesia Boulevard, one of the city’s most dangerous roadways. An open streets initiative started in 2015, Beach Streets, has proved hugely successful, drawing as many as 50,000 participants. The next Beach Streets, this November, will be held in the heart of the city’s Cambodian community, one of the world’s largest Cambodian populations outside Southeast Asia.

Local Advice

At the Downtown Long Beach Bike Fest you can peruse a vintage bicycle show, tackle a City Cross obstacle course—featuring sand pits, dumpsters, and barricades throughout the Arts District—and kick back at the Beachwood Brewing & Friends Craft Beer Garden whilst sipping a Lambic-inspired Fortune Favors the Funk ale and listening to the brass-infused pop group, Tall Walls.

29: Gainesville, Florida

Gainesville has long served as a beacon of hope in the state of Florida, the most dangerous state in the U.S. for bike riders. The city touts regional trails that connect with surrounding communities, a newly protected bike lane and pilot bike share program, and one of the nation’s highest percentages of U.S. Census counted bike commuters (6.2 percent).

Perhaps Gainesville’s biggest accomplishment in the last two years is the rise of a local advocacy group, Gainesville Citizens for Active Transportation. By educating and vetting city and county political candidates on transportation issues, and then endorsing candidates at election forums, GCAT has cultivated leaders well versed on cycling issues (i.e. they “get it”). In May, during bike month, Gainesville mayor Lauren Poe biked to work every day. And, in responding to a Gainesville Sun story on bike safety, City Commissioner Thomas Hawkins said, “the biggest problem is driver behavior. The way to address that is with education, enforcement and—this is the big one—engineering.”

Still, according to GCAT President Chris Furlow, funding remains a primary issues. Voters have rejected sales tax increases to repave roads and build bicycle infrastructure—and safety focused efforts to add bike lanes to road reconstruction projects often take years to accomplish.

Local Advice

The Menagerie in Motion kinetic derby, hosted by the Active Streets Alliance each February, features sculptures powered by up to 12 riders. Award categories include Best Pun, 2nd Most Mediocre, and Most Audacious Breakdown.

30: Chattanooga, Tennessee

Chattanooga has long garnered acclaim for its abundance of mountain and river recreation opportunities—from 22 miles of singletrack at Raccoon Mountain to the daunting ascent of Lookout Mountain. A vast park fronts the Tennessee River, bike-share stations dot downtown, and the city’s core has become increasingly populated. Boosting biking’s utilitarian appeal seemed uncontroversial in 2014, when Chattanooga began the aggressive implementation of a modern new bike network—slated to bring 23 miles of multiuse paths and 40 miles of boulevards to the city. But when the crews broke ground on the first curb protected bike lane, running right down Broad Street, local business owners expressed outrage and confusion over the new infrastructure, and the city found itself having to extol the benefits of biking.

Similar projects, in cities like New York, Salt Lake City, and Indianapolis, have boosted retail sales by more than 50 percent, and made streets safer, reducing crashes by 30 percent or more. A proposed rightsizing (reconfiguring streets to better serve all types of road users) of Chattanooga’s MLK Boulevard, which adjoins Broad Street, could bring much needed economic development to a once vibrant section of the city, where Bessie Smith first sang the blues. And the new $16 million, 3-mile extension of Chattanooga’s riverfront trail, which opened in August, could serve as key commuting corridor.

Chattanooga’s police force also supports cycling. The chief, Fred Fletcher, plastered police cruisers with three-foot passing logos and used stings to educate drivers who buzz bike riders. In a single year, such efforts helped reduce bicycle and car collisions by 26 percent.

Local Advice

The iBikeCHA initiative incentivizes residents who pledge to commute by bike, and log their rides on the city’s Green Trips website. Downtown Chattanooga’s Electric Bike Specialists offers up to 35 percent off the purchase of a bike to customers who commit to recording their summer bike commutes, Suck Creek Cycle gives $25 gift cards to people who take a city-run bike safety class, and the top bike commuter during the months of June and July won a fully loaded town bike from Cycle Sport Concepts.

31: Louisville, Kentucky

“Louisville has gotten in the habit of reducing lane widths and painting buffered bike lanes,” says Chris Glasser of the advocacy group Bicycling for Louisville. That practice, designed to reduce vehicle speeds and make bike riders more comfortable, has led to a number of wide bike lanes running through the city’s downtown—and has helped Louisville create an increasingly vibrant urban core.

In 2014, Louisville opened the bicycle- and pedestrian-dedicated Big Four Bridge, a historic steel structure linking downtown Louisville with the quaint town of Jeffersonville, Indiana across the Ohio River. During the city’s Wednesday evening summer concert series, hundreds of cyclists now stream across and gather around the bridge to enjoy complimentary tunes and take advantage of bike parking from the Park Side bike shop.

However, despite the city’s feel-good bike vibe, frustrations endure. The mayor’s proposed budget for bicycle infrastructure was reduced by half. A nascent system of neighborways (roads prioritized for bicyclists) lacks the kind of infrastructure, such as traffic diverters, to make them truly effective. And, where peer cities like Indianapolis and Pittsburgh boast impressive protected bike lanes and bike share systems, Louisville is just beginning to implement them—it recently installed its first 2 miles of protected bike lanes and is planning to launch a bike-share program in 2017.

Local Advice

Louisville’s Broken Sidewalk blog is perhaps the nation’s best local outlet chronicling a city’s urban transformation. The site’s clean design and enlightening content regularly features posts from some of the country’s top thinkers on utilitarian cycling. Every city that wants to improve biking needs an online publication this good.

32: St. Paul, Minnesota

After approving an updated bike plan in 2015, Saint Paul has tentatively begun implementing more modern and safer cycling infrastructure on the city’s major roadways. An initial hurdle came with the installation of bike lanes along Cleveland Avenue, which connects residential areas with local businesses and runs past two universities—and called for the removal of some on-street parking. After months of contentious public comment the city council voted in favor of the bike lane, and adhered to the plan the city had set forth.

In 2016, Saint Paul began work on two ambitious trail projects: installing the first 2.5 miles of the Grand Round, a 26-mile loop of trails circling the city; and breaking ground on the critical first leg of the Downtown Bike Network, a series of protected bike lanes that will guide bike riders from the Mississippi River waterfront through the center of the city to the 18-mile Gateway State Trail.

Without dedicated funding for ambitious bike projects, Saint Paul has piggybacked much of its bike plan on existing road repaving projects, creating a segmented network. Though Saint Paul shares the Nice Ride bike share program with Minneapolis, with more than 50 of the system’s 190 stations in its city limits, ridership in Saint Paul accounts for just 10 percent of the entire Nice Ride usage.

Local Advice

Enjoy a traffic-free tour of the Capital City’s parks, parkways, and historic neighborhoods during the annual Saint Paul Classic Bike Tour, which draws more than 5,000 riders and supports the Bicycle Alliance of Minnesota. Newbie bike riders can link up with Saint Paul Women on Bikes, which offers free Adult Learn to Ride classes, a five-course series designed to boost cycling skills.

33: Grand Rapids, Michigan

In May of 2014, the residents of Grand Rapids voted to retain a citywide income tax that added an additional $4 million annually toward reconstructing the city’s deteriorating roads. Already, the repaving has proved a boon for people pedaling bikes in this city. A two-way cycletrack now runs one mile along the length of Riverside Park leading toward downtown. The 3.5-mile Seward Avenue Bikeway features a fix-it station and a parking shelter with 12 bike lockers. And an alternative proposed cycling corridor on Jefferson Avenue that connects surrounding neighborhoods with the city’s center may include Grand Rapids’s first “advisory bicycle lane,” in which car drivers share a wide center lane with bike lanes on either side.

The city’s roughly 100 miles of bike lanes and trails exemplify how quickly a city can transform its roadways to accommodate bike riders. In 2010, no (yes, zero) bike lanes existed in Grand Rapids. Though current Census data doesn’t capture the city’s recent cycling efforts, city officials and local advocates claim ridership is way up. Last year, with the assistance of a $600,000 federal grant, the city launched an educational campaign—including comical videos portraying bike riders and drivers in group therapy sessions—that aims to inform all users of their rights and responsibilities on the road.

Local Advice

The parks surrounding Grand Rapids contain more than 60 miles of singletrack primarily maintained and constructed by the Western Michigan Mountain Bike Alliance. Local events range from the Grand Rapids Dirt Dawgs kids’ races to the Skirts in the Dirt women’s race series, as well as the more anarchic King of the Ring at the city’s urban bike park, a weeknight race featuring bikes, booze, and bloody knees.

34: Alexandria, Virginia

Alexandria sits adjacent to both our nation’s capital and Arlington, Virginia, cities with a growing amount of on-street infrastructure (such as protected bike lanes) designed to encourage bike riding. Yet, despite a network of paths alongside its waterways, until recently Alexandria had few bike lanes, and none offering bike riders physical protection from motor vehicles. According to the city, a complete streets policy from 2011 was “reenacted in 2014, recognizing that the users of our transportation system include pedestrians, bicyclists, riders, and drivers of public transportation, in addition to motor vehicle drivers.” The result? Lots of public outreach, and roadway reconstructions that actually serve a wide array of users.

In 2013, bike lanes on King Street which runs from a residential area into the city’s Old Town, became the center of what local media dubbed a “culture war,” after a Wall Street Journal columnist railed against the removal of 27 parking places on the arterial thoroughfare. Despite the bikelash, the city moved forward with the bike lane striping. And about a year later, when Alexandria proposed striping an adjoining section of King Street, 66 percent of residents voiced support of the design featuring buffered bike lanes.

The city’s hiring of a complete streets coordinator has helped facilitate the redesigning of Alexandria’s roadways, meeting with residents ranging from local church groups to preschool staffers to discuss how street improvements like protected bike lanes will make the road safer for all users—regardless of their mode of travel. That’s a message that Alexandria’s residents seem to increasingly support.

Local Advice

A partnership between the National Park Service and the Washington Area Bicyclist Association will soon transform an unused parking lot in Jones Point Park, beneath the Alexandria end of the Wilson Bridge, into a Bike Campus, where kids (and adults) can safely learn to navigate a practice layout of city streets and bike infrastructure, from dedicated bike lanes to shared lane markings.

35: Albuquerque, New Mexico

The passage of a complete streets policy in 2015 has begun to revolutionize the transportation landscape in Albuquerque. Major roadways—such as Martin Luther King Boulevard, a dangerous arterial with uncomfortably narrow bike lanes and roomy motor vehicle lanes that encourage speeding—are rapidly being rebuilt with wide bike lanes and generous four-foot buffers between bike riders and car drivers.

In 2009, the city designated Silver Avenue a Bicycle Boulevard but failed to build out much of the infrastructure that prioritizes bicycle riders over motor vehicle drivers. But in 2016, Albuquerque addressed this oversight, and revealed a new plan for the Bicycle Boulevard with amenities like concrete barriers to protect riders at intersection crossings, and traffic diverters to limit motor vehicle volume. As part of its commitment to link 50 miles of trails ringing the city, Albuquerque is resurfacing the worn-out wooden bridges with a new surface. The city's bike share launched on Bike to Work Day in 2015.

Local Advice

The advocacy group BikeABQ has long provided a bike valet at Albuquerque’s nine-day International Balloon Fiesta; now the city offers the service at events ranging from the New Mexico Wine and Jazz Festival to the Freedom Fourth celebration, further encouraging residents to arrive via pedal power.

36: Cincinnati

The momentum that propelled Cincinnati to a first-time top 50 ranking in 2014 continued on many fronts over the last two years. The city launched an ever-expanding bike-share system, Red Bike, that’s engaged an entirely new populace of bike riders—74 percent of users reported they had never or rarely ridden a bike before. The first 5-mile right-of-way of an envisioned 42-mile regional trail plan, Cincinnati Connects, was purchased for $12 million. And, the city’s once-contentious Central Parkway protected bikeway has become a permanent fixture, ushering cyclists into downtown. Today, parents pedal with kids in tow down the wide bike lanes, and according to advocate Frank Henson of Queen City Bike, “a number of developers have cited the Central Parkway bike lanes as their reason for building alongside the roadway.”

On one front, though, the full build-out of Cincinnati’s on-street bike network, the city has failed its rapidly growing urban cycling populace (ranked the third fastest growing bike community in the country). Since 2014, little progress has been made on a progressive bike master plan approved in 2010.

However, the lack of physical progress hasn’t dampened local bike riders’ enthusiasm for cycling. Rides and cycling clubs abound. The Urban Basin Bicycle Club leads a weekly social ride from downtown into outlying neighborhoods, and CORA, the Cincinnati Off-Road Alliance, has steadily built out a 60-mile network of singletrack within an hour’s drive of Cincinnati.

Local Advice

Experience Cincy’s flourishing bike polo scene by joining one of the Cincinnati Hardcourt League’s twice-weekly pickup games—held at the Evans Street Playground in the Lower Price Hill neighborhood, just minutes from downtown. Or participate in the semiannual Cincinnati Three Way tournament (named after the city’s iconic chili), a triathlon of sorts in which teams compete in bike polo, foosball, and flip cup.

37: Sacramento, California

The American River Railway runs 32 miles from downtown Sacramento to Folsom Lake, and for more than three decades has served as a jewel of Sacramento’s cycling infrastructure, serving both bike commuters and recreational riders. But where the trail borders a large swath of parkland on the northern banks of the American River, homeless encampments and debris have diminished the trail’s use. In 2016, the Sacramento County Parks Department voted on a three-year pilot program allowing off-road riding on maintenance and fire roads in the open space bordering the American River Parkway. “By harnessing the parkland as a mountain biking amenity we hope to diminish illegal camping, increase the usability of the paved trail where it passes through the city, and evaluate environmental impacts,” says Jim Brown, executive director of the Sacramento Area Bicycle Advocates.

However, even with its impressive trail network, an increasing number of downtown developments (such as the new Golden 1 Center arena), and a large contingent of bike commuters, Sacramento lacks any progressive bike infrastructure, such as protected bike lanes and bicycle boulevards. Brown says a long-awaited bike plan update (four years in the making), an Active Transportation coordinator hired from noted planning agency Alta Planning + Design, and a new mayor with a history of combatting climate change and air quality may finally move Sacramento in the right direction—and in line with nearby peer cities Davis and Oakland.

Local Advice

Visit midtown Sacramento’s Edible Pedal bike shop to drool over a built-to-order town bike or sip a locally roasted pour-over coffee, or have the shop’s bicycle delivery service bring you a meal from one of the city’s many Farm-to-Table restaurants.

38: Tallahassee, Florida

In the 1990s, Tallahassee embraced “smart growth” policies that limited sprawl and helped shape the capital city’s compact nature. Developers who build within the city’s core pay reduced fees and are incentivized to construct projects with a multimodal mindset. Large urban parks draw major musicians and also host weeknight music festivals. Paved and mixed-terrain bike paths dot the city—including the Tallahassee-St. Marks Historic Railroad State Trail, which runs 16 miles south to the coast. And quick and easy access to tree-canopied rural roads and rolling singletrack has long made the city a mecca for road, gravel, and mountain biking. “It’s not uncommon for staffers to ride in on Friday, and head out for a weekend bikepacking trip in the Apalachicola Forest after work,” says Barry Wilcox of Tallahassee’s planning department.

So when the city’s bike coordinator, Artie White, discovered Tallahassee would be repaving two major thoroughfares running through the heart of downtown, he proposed a 5-mile network of protected bike lanes that would connect the city’s major universities, Florida State and Florida A&M;, with the capital building and a new $7.2 million bicycle-pedestrian bridge at Cascades Park. “We came up with a design and presented it to the city’s officials, and everyone seemed to think it was a good idea,” says White.

The first phase of Tallahassee’s Downtown-University Protected Bike Lane Network was unveiled in the summer of 2015, using plastic bollards and parking medians to delineate bike riders from motor vehicles, and was accompanied by a city-produced YouTube video educating users on the new infrastructure (for example, reminding people that bike riders are still allowed to ride in the general travel lanes). Smart, indeed.

Local Advice

Parents who think having kids means no more bike commuting can link up with Tallahassee’s Joyride Bicycle Collective on Facebook. The social cycling group focuses on providing a supportive environment for cyclists of any age and ability, with repair workshops, commuter breakfasts, and group rides, including a family-oriented outing to the city’s summer concert series.

39: Columbus, Ohio

The Executive Director of Yay Bikes!, Catherine Girves, likes to tell this story: When city engineers were drawing up new plans for a buffered bike lane in downtown Columbus, they asked the local advocacy group to look over the documents. Instead, says Girves, Yay Bikes! suggested a bike ride. “At first, their body language was very closed off, you could see they didn’t feel comfortable riding in traffic,” Girves says. “But after a few blocks, they realized, ‘Oh, people can actually ride bikes alongside car traffic.’” Soon, the engineers were pulling out their plans, and making notes where Yay Bikes! members pointed out potential conflicts. At the end of the ride, says Girves, they asked, “Can you come on another ride with us?”

Today, these rides—Yay Bikes! calls them “professional development”—are the norm for city and state transportation officials, economic development wonks, and (soon, says Girves) even local judges. The beneficiary? People who ride bikes in Columbus, one of the fastest growing cities in the U.S. “There’s now a commitment to stopping the sprawling development patterns,” says Girves. The city started a bike share program in 2013, and opened its first protected bike lane in 2015, all part of a wider multimodal planning project called Connect Columbus. The city’s police chief, an avid bike commuter, has been educating officers on cyclists’ rights.

Local Advice

Founded just eight years ago, the two-day, 130- and 180-mile Pelotonia ride has become the country’s largest single cycling fundraiser in support of cancer research. So far, riders have raised $122 million, with one hundred percent of each rider’s contribution going to the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center.

40: Miami

Miami boasts one of the nation’s most vibrant and diverse cycling scenes. On the final Friday of every month as many as 4,000 riders congregate for the city’s Critical Mass. With police assistance, residents of all ages and ethnicities take over the city’s streets. (During his tenure with the Heat, LeBron James often attended the ride.) On a weekly basis, locals gather for Taco Tuesday and Thirsty Thursday rides.

But while in previous years Miami offered bike riders new cycling infrastructure and hope of a safer future, the pace of progress has slowed considerably. The city’s bike network remains patchwork and lacks any of the low-stress cycling infrastructure—like protected bike lanes and bicycle boulevards—that’s become common in many other American cities. Biking in Miami remains far too dangerous.

Two planned trail projects, the Ludlam Trail west of central Miami, and the Underline, a linear park below the city’s metro rail line, could form the spines of an impressive bike network. Miami’s robust bike-share system begs for better infrastructure downtown. And, the city, Dade County, and the Florida DOT deserve credit for proposing protected bike lanes on the dangerous bridges over the causeway. But a city such as Miami, with natural amenities like sun and flat and wide roads, can do better for its bike riders.

Local Advice