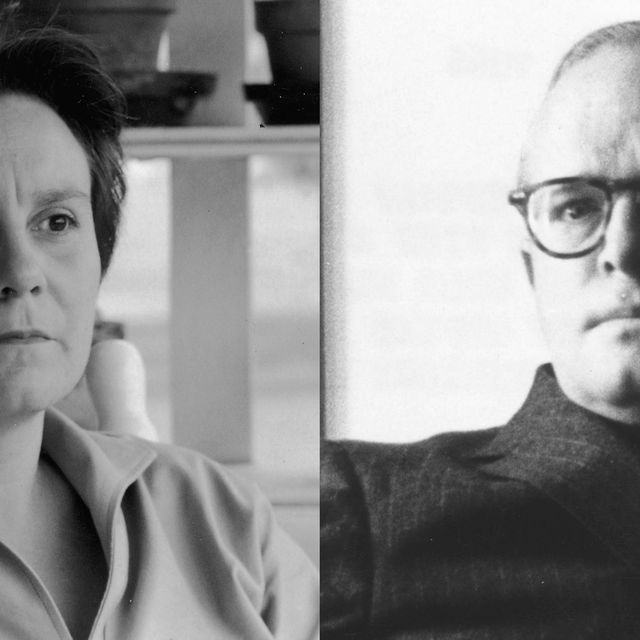

Two of the most famous authors of the 20 century, Harper Lee and Truman Capote bonded as children in the Depression-era Deep South. More than two decades later, they both found critical and financial success, but rampant jealousy and their clashing lifestyles led to the end of one of history’s most legendary literary friendships.

Each became a character in the other’s work

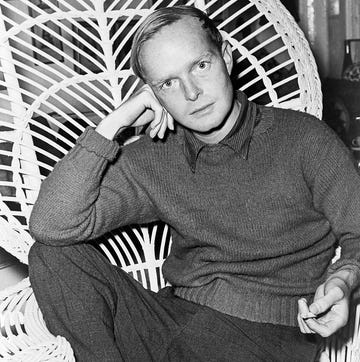

The son of a teenaged mother and a salesman father, Capote (then known as Truman Persons) moved to Monroeville, Alabama at age 4 to live with his aunt following his parents’ divorce. He soon befriended Nelle Harper Lee, the daughter of a well-regarded lawyer and journalist, A.C. Lee. The young pair bonded over their shared love of reading and developed an early interest in writing by collaborating on stories written on a typewriter purchased for them by Lee’s father.

Although she was two years younger, Lee acted as Capote’s protector, shielding the tiny, highly sensitive boy from neighborhood bullies. Lee would later say that she and Capote were united by “common anguish” over their childhoods, as Capote’s troubled mother repeatedly abandoned him as she sought financial security, and Lee’s mother suffered from what scholars now believe to be bipolar disorder.

Their friendship continued even after Capote moved to New York City to live with his mother as a pre-teen. Forgoing college, the precocious Capote landed a job at The New Yorker magazine and published a series of pieces that caught the attention of publishers, leading to a contract for his first book. In 1948, Other Voices, Other Rooms, his first novel, was published. Its main character, Joel, was based on Capote. The tomboy character of Idabel Tompkins was a fictionalized version of Lee. Capote’s early success convinced Lee moved to New York City the following year. She began working on her own book, To Kill a Mockingbird, depicting her Alabama childhood and basing the character of Dill Harris on Capote.

Lee played a crucial role in Capote’s most famous work

In November 1959, Capote read a brief story in The New York Times about the brutal murder of a wealthy family in a small Kansas town. Intrigued, he pitched the idea for an investigative story to The New Yorker magazine, whose editor quickly agreed. As Capote made plans to head west, he realized he needed an assistant. Lee had just submitted her final manuscript for To Kill a Mockingbird to her publishing house and had ample time on her hands. Lee had long been fascinated by crime cases and had even studied criminal law before dropping out of school and moving to New York.

Capote hired her, and the two made their way to Holcomb, Kansas, a few weeks later. Lee proved invaluable, as her comforting Southern manner helped blunt Capote’s more flamboyant personality. Decades later, many in Holcomb still recalled Lee with fondness, while seemingly holding Capote at arm’s length. Thanks to Lee, local residents, law enforcement and friends of the slain Clutter family opened their doors to the unlikely pair.

Each night, Capote and Lee retired to a small motel outside of town to go over the events of the day. Lee would eventually contribute more than 150 pages of richly detailed notes, depicting everything from the size and color of the furniture in the Clutter home to what television show was playing in the background as the pair interviewed sources. She even wrote an anonymous article in a journal for former FBI agents in early 1960, which praised the lead detective on the Clutter case and promoted Capote’s ongoing work. Her authorship of the article in The Grapevine wasn’t revealed until 2016.

Jealousy helped sour their relationship

To Kill a Mockingbird was published in July 1960, and became a runaway success, earning Lee a National Book Award and a Pulitzer Prize, followed by an Academy Award-winning motion picture. It would eventually sell more than 30 million copies and become a beloved classic. Capote’s jealousy over Lee’s financial and critical success gnawed at him, leading to a growing rift between the two. As Lee would write to a friend many years later, “I was his oldest friend, and I did something Truman could not forgive: I wrote a novel that sold. He nursed his envy for more than 20 years.”

Despite the tension, Lee continued to help Capote on the Clutter project, as he became increasingly obsessed with the case, developing relationships with the two men convicted and eventually executed for the crime. It took him nearly five years to publish his New Yorker series, which he then expanded into a book. When In Cold Blood was published in 1966 it too was a sensation, with many hailing Capote for creating a new genre, the “true crime” narrative non-fiction.

But some, including Lee (at least in private), criticized his willingness to alter facts and situations to fit his narrative. She would later describe Capote in a letter to a friend, noting, “I don’t know if you understood this about him, but his compulsive lying was like this: if you said, ‘Did you know JFK was shot?’ He’d easily answer, ‘Yes, I was driving the car he was riding in.’”

Despite her years of work and her unending public support of Capote’s work, he did not officially recognize her contributions to In Cold Blood, instead of mentioning both her and his lover in the book’s acknowledgments section. Lee was deeply hurt by the omission.

The two clashed over Capote’s self-destructive lifestyle

Capote’s literary career went into decline following In Cold Blood. Though he wrote a number of articles for magazines and newspapers, he never published another novel. Instead, he became a fixture of the post-war jet set, partying and befriending a number of high-profile figures, including a group of mostly married, wealthy women who he dubbed his “Swans.” In 1975, Esquire magazine published a chapter of Capote’s unfinished book, Answered Prayers. The excerpt, a thinly-veiled account of the lives and scandalous loves of many of Capote’s society friends, was a disaster, leading many of them to ostracize him and leaving his literary career in tatters.

As Capote descended into a life of alcohol, drugs, television show appearances, and Studio 54 night-clubbing, the publicity-phobic Lee pulled away from the spotlight entirely. She lived quietly in Alabama, along with under-the-radar trips to New York City. Her refusal to grant interviews and the lack of a follow-up to Mockingbird led to decades of rumors that it actually was Capote who had written all or part of the book – although the publicity-mad Capote certainly would have revealed his role if that had been the case.

By the time of Capote’s death in 1984, he was estranged from many of the people with whom he’d once been close, including Lee. She died in 2016 just months after the publication of Go Set a Watchmen, an early version of To Kill a Mockingbird, which Lee had set aside in the 1950s. The book raced up the charts, although fans of Mockingbird were shocked to discover a far less idealized version of Atticus Finch, the lawyer character based on Lee’s father. But this first draft did include remembrances from Lee’s early years, including Dill Harris, easily recognizable as the brash young boy named Truman whom the shy Lee had befriended years before.