Union Military Hospital in Washington DC

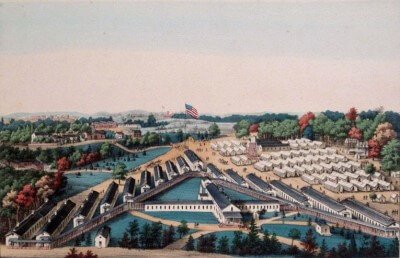

Armory Square Hospital had twelve pavilions and overflow tents containing one thousand hospital beds filled with wounded from the battlefields of Virginia. The wounded were brought to the nearby wharves in southwest Washington and then taken to the Hospital. It was one of the largest Civil War hospitals in the area and one of many medical facilities located in downtown Washington, DC.

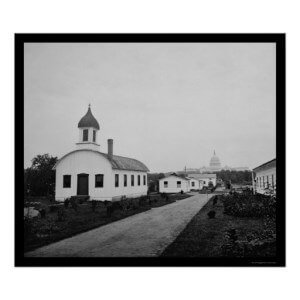

Image: Chapel and buildings at Armory Square

Completed U.S. Capitol in the distance

Constructed in 1862, Armory Square took its name from the Old Armory on the Mall, around which the hospital was built. the medical facility spread accross the Mall and included quarters for officers, service facilities and a chapel. Situated nearest the steamboat landing at the foot of Seventh Street SW and the tracks of the Washington and Alexandria Railroad, Armory Square was the only stop for the most severely injured, those who were unable to travel any farther.

Armory Square was one of the six model hospitals constructed in Washington, DC during 1862. Whereas barracks hospitals were converted from unused Army barracks, model hospitals like Armory Square were specifically made according to the U.S. Sanitary Commission and their recommendation of pavilion style hospitals. There were as many as 56 separate facilities used as hospitals in Washington D.C. during the course of the Civil War.

Pavilion Hospitals

Prior to the Civil War, any system of hospitalization was virtually unknown. With the large number of wounded and sick needing long-term care, a network of general hospitals was created in cities in both the North and the South. At first existing buildings were used for hospitals, but soon both armies constructed large pavilion-style hospitals that were clean, well-ventilated, and highly-efficient.

Surgeons, hospital stewards, both male and female nurses, matrons, laundresses and volunteers from civilian associations all contributed to the care of the sick and wounded in these pavilion hospitals. The quality of care that the patients received improved dramatically after the opening months of the war.

The layout of the hospital resembled a solar system, where all wards revolved around the surgeon in charge, and each ward turned on its own axis, with its own surgeon and female nurse, an orderly for both, ward master, cadet surgeon to dress wounds, three attendants, and two night watchers.

President Abraham Lincoln often visited the hospital and took a special interest in it. Armory Square nurse Amanda Akin, who published a memoir of her experiences in 1909, remembered that Lincoln’s eyes had a sad, far-away look as he shook hands with each soldier. She noted that he paused before those suffering the most to offer a warm God bless you:

It was pathetic to see him pass from bed to bed and give each occupant the warm, honest grasp for which he is noted. I hear that he is especially interested in this hospital, and has suggested having flower beds made between the wards with plants from the Government gardens.

Nurses of Armory Square Hospital

Nurses assigned to Armory Square Hospital worked under Army regulations, and Dorothea Dix, Superintendent of Union Army Nurses, was in charge of Armory Square. Dix was a strong willed person who often ignored orders, and her perseverance gave her the nickname Dragon Dix. She recruited over 2,000 female nurses, and under her direction nursing was greatly improved.

Sarah Low

This compassionate lady from Dover, New Hampshire undoubtedly learned a great deal about the treatment of the sick from her physician father, and much of her life was spent taking care of friends and family members. Like many patriotic women at the outbreak of the Civil War, Low felt she could best help the Union cause by tending to soldiers wounded in battle.

In September 1862 she traveled south to Washington, DC, where she first served as a nurse at the Union Hotel Hospital in Georgetown, DC. She arrived at Armory Square in October 1862 and served there until August 1865. She wrote many letters home, some of which are quoted here.

We are up at six, dress by gas-light. Our rooms are at the end of the wards and often just a curtain for privacy. The air is very bad and the ventilation poor. One has little appetite for food. There is often no competent head in the wards. Good, bad and indifferent nurses, surgeons and attendants complicate matters. Some of the doctors are splendid men, others absolutely incompetent.

A group of ladies in Dover formed a society to furnish soldiers from the State of New Hampshire with articles necessary to health and comfort. They operated throughout the war and sent large contributions:

Almost all supplies of linen etc are sent to the front, and every 3 or 4 days the hospital supply gives out. Tent wards are continually being added and the number of patients increases faster than the extra supplies arrive. The boxes we receive from the Soldier’s Aid Societies, families and friends supplement our needs and are a great help.

An interesting list of articles sent to Miss Low for her ward by the Hartford Soldier’s Aid Association included the following. Box no. 417 (showing the number of boxes sent out) contained 9 bottles blackberry brandy, 1 bottle wintergreen cordial, 1 can sweetmeats and sponges. Box no. 418 contained 12 boxes of lint, hospital napkins 144, 6 pieces of mosquito netting, 8 hop pillows, 3 everlasting pillows, dried currants, 10 pkg. old linen, 24 feather fans and 2 linen coats.

Sarah Low was at home in Dover in April 1865, apparently on furlough. Among her papers was an urgent note from Dr. Bliss dated April 15, 1865 merely saying, “Your services are much needed, hope you will come at once.” Low was on her way back to Washington before the note from Dr. Bliss reached her, for in her diary dated April 15 she was in Boston:

After breakfast as I was going out Mary (Hale) and her father stood by their door very much overcome saying they had bad news. President Lincoln had been assassinated.

Sarah Low left Boston for Washington that night arriving April 17. On April 18 she wrote in her diary:

We started for the White house to see President Lincoln’s remains, the crowd was great and beyond anything you can imagine though there was perfect order. We did not attempt to go in but mean to go again.

On April 20, Low wrote:

Miss [Anna] Lowell and I went to the Capitol to look at the President, we thought we might regret it if we did not. There was a long procession waiting to go in which moved a step or two and then stopped, and so on. It was a very impressive sight in the Rotunda, in the dim light as we entered we saw on one side a line of officers sitting in full and brilliant uniform. In the center was the coffin, an officer standing at the head and foot…. Lincoln’s face looked very thin and shrunken, the face was dark and it seemed to me that he looked like a murdered man.”

On June 16, 1865, she wrote:

I had hoped to make plans to start for home but Dr. Bliss said that he had never needed his lady nurses so much as now especially the old experienced ladies. In the constant change of attendants they are the chief dependence.

Sarah Low finally returned home in August 1865.

Anna Lowell

Anna Lowell

The Lowells are a distinguished family from Cambridge, Massachusetts. Anna Lowell was the niece of poet James Russell Lowell, and sister of Lt. James Jackson Lowell and Brig. General Charles Russell Lowell. In summer 1862, having recently been trained as an Army nurse, Anna was assigned as a nurse on the hospital ship Daniel Webster on the James River.

Image: Anna Lowell, seated, with Ward I nurse Sarah Low

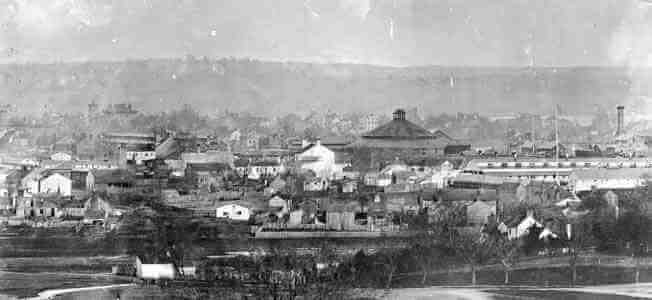

Armory Square Hospital, circa 1863

When she arrived at Harrison’s Landing, Virginia in June 1862, she continued her work despite news that her brother James had been killed in the Seven Days Battles during the Peninsula Campaign. James Jackson Lowell was mortally wounded at Glendale on June 30, 1862; he was interred near the battlefield. After the war, Anna brought his body home for burial in the Lowell family plot at Mount Auburn Cemetery.

In November 1862, Anna Lowell was assigned to Ward K at the Armory Square Hospital. She served there until August 1865, at one point also having charge of the special diet kitchen for eighteen months. Her brother Charles Russell Lowell was mortally wounded at the Battle of Cedar Creek on October 19, 1864.

Two days later Anna went to the office of Secretary of State Edwin M. Stanton, searching for news about her brother. There she learned of Charles’ death directly from his fellow officer General George Armstrong Custer. Charles’ wife was Josephine Shaw Lowell, philanthropist and sister of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, commander of the 54th Massachusetts, U.S. Colored Troops, who lost his life at the Battle of Fort Wagner in South Carolina on July 18, 1863.

Armory Square Hospital badly needed the services of Anna Lowell; therefore, she did not attend her brother’s funeral in Cambridge with the rest of her family. Charles’ death was announced in the hospital newspaper, the Armory Square Hospital Gazette. Anna remained in the overwhelmed Armory Square Hospital wards while the rest of her family mourned in Cambridge.

Following the war, Lowell married a prominent D.C. physician, Henry E. Woodbury, but the marriage quickly soured. Anna then returned to Cambridge. When General Charles Howard, a Freedmen’s Bureau commissioner, asked for help in finding work for former slaves then crowded into Washington, Lowell led the committee that founded a school for that purpose in 1865.

The Howard Industrial School for Colored Women and Girls educated freed slaves in housekeeping skills and then helped them find jobs. The Freedmen’s Bureau would send newly freed women to Cambridge when there were places available. The school received 200 requests from people who wanted to hire domestic help before it opened its doors.

Anna Lowell was a pioneer in the industrial arts movement, as her work inspired the formation of the National Industrial Association. In 1879, she established the Mission School of Cookery in Washington, DC to teach the basics of cooking. The school included African Americans among its students. In 1889 Lowell published the cooking manual used in D.C. public schools.

Amanda Akin

The large and prosperous Akin family had lived in the Quaker Hill community north of New York City for generations. The eighth of Judge Albro Akin’s ten children, Amanda was thirty-five when she traveled from her home to Washington, DC to serve as a nurse. Arriving at Armory Square Hospital on April 28, 1863, Amanda Akin reported to Dr. D. W. Bliss and was assigned as a nurse in Ward E.

Nursing was not yet established as a profession, and most women who took on this role were expected to learn as they went about their daily activities. Akin describes her first evening at Armory Square:

I meekly followed [the nurse] through the long ward, unable to return the gaze of the occupants of the twenty-six beds, and with a sinking heart watched her raise the head of a poor fellow in the last stages of typhoid, to give him a soothing draught. Could I ever do that? For once my courage failed.

During her fifteen months at the hospital, Akin wrote long letters to her sisters and recorded her daily experiences in diaries, including the daily routine at the hospital: After reveille sounded at 6 a.m. the nurses dressed, tidied their rooms, and dispensed medications. They then served breakfast to their patients before eating their own. Constant supervision of the patients was the order of the day in addition to reading and writing letters for soldiers.

More medicines were dispensed before noon, followed by lunch. During the afternoon, nurses relaxed, rested or went on outdoor walks. At 5 p.m. nurses gave their patients another round of medicine. Evenings were spent trying to entertain the men. The night watchers arrived at 8:45 p.m. and nurses gave them final directions before retiring for the night.

Amanda Akin wrote in her first letter home:

My Dear Sisters: You are no doubt anxiously looking for a sign of life from me, but I can tell you initiation into hospital life of such a novice is not lightly to be spoken of, and until my ideas ceased floundering and I could recognize my old self again, I could not trust myself with a pen.

Hospitals received an influx of patients following major battles, putting greater demands on all staff and confronting nurses with the severe wounds caused in conflict. In a letter to her sister dated May 14, 1863, Akin writes:

Since the wounded from the battle of Chancellorsville have arrived, our life has become very exciting and absorbing… We looked for them the first of the week, and when the heavy ambulances went past in procession, taking those least wounded to more remote hospitals, I, at least, became possessed of an undefined dread.

On Thursday morning at daybreak they arrived, about one hundred and fifty, and on Friday one hundred more. The sound of the general ward master’s bugle took us out of our beds. I shall never forget the scene as we looked from the window into the darkness, only relieved by the lanterns in the hands of those waiting to receive them, as the ambulances were driven slowly up one by one, and their burden carried in either on a stretcher or between two men, if only the lower limbs were injured. My friend had already “wrestled” herself into her clothes, and I did not tarry.

The wounded had been put in haste on the floor, on chairs, anywhere, but all nervousness was gone when I saw their brave hearts reflected in the faces of those able to sit up. One man at once arrested my attention; he was sitting by the stove, with one foot covered with bloody cloths, drawn over his knee, his clothes torn and soiled, telling some listeners about the battle in exciting terms, with his bright black eyes glistening, and forgetting the loss of two or three toes!

Even the severely wounded men who could speak were cheerfully waiting their turn to be bathed and put in bed, thankful to get to such a comfortable place… Time will not permit to tell you more. Suffice it to say, they are a brave, noble set of fellows, and with scarcely an exception bear their great sufferings without a murmur.

Akin returned home July 20, 1864, after serving at Armory Square Hospital for 15 months. She married Dr. Charles W. Stearns in 1879, was widowed in 1887, and apparently had no children. In 1909, at age eighty-one, she published an account of her nursing experience, The Lady Nurse of Ward E, under her married name, Amanda Akin Stearns. She died in February 1911 and is buried with her husband in Pawling, New York.

Image: Ward in Armory Square Hospital

Image: Ward in Armory Square Hospital

Armory Square Hospital was open for only three years (1862-1865), but in that time it administered to over 13,000 sick and wounded soldiers. The hospital employed individuals from privileged backgrounds as well as newly freed slaves, and served as a temporary home for a staff of several hundred people, including surgeons, clerks, attendants, nurses, cooks, laundresses and guards. After the war, Armory Square Hospital was closed.

SOURCES

Smithsonian: Diary of a Civil War Nurse

History Engine: Armory Square Hospital

Smithsonian: Searching for Anna Lowell

Cambridge Woman Pioneered Cooking School for Girls