Story highlights

Officials blame drug trafficking for more than 70% of Puerto Rico's homicides

The U.S. commonwealth's murder rate is five times the national average

Puerto Rico's governor calls for more federal assistance

Lawmaker: The increase in violence "is alarming and unacceptable"

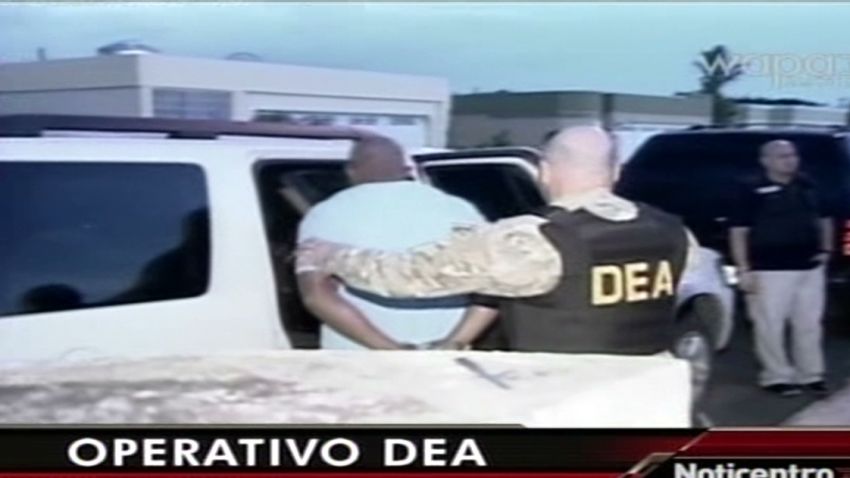

Swarms of agents closed in on Puerto Rico’s main airport, arresting workers who allegedly crammed cocaine-filled luggage onto commercial planes as part of a far-reaching smuggling scheme.

A special strike force intercepted an unmarked fiberglass boat near a beach town, confiscating bales of cocaine and heroin with a street value of $8 million.

Both raids this week were significant blows in the battle against drug trafficking, authorities said.

Drug raid targets baggage handlers, airline workers in Puerto Rico

But they were also reminders that Puerto Rico faces a grisly reality.

Inside the Caribbean island territory known by many Americans as a scenic tourist destination, U.S. citizens are gunned down and stabbed daily in drug-fueled attacks as rival traffickers feud over turf and addicts fight for another fix.

Last year, a record 1,136 people were slain within the island’s borders. Officials say Puerto Rico’s murder rate is five times the U.S. national average.

Photos: Violence in Juarez not going away

Drugs are behind more than 70% of the homicides, local officials have said, arguing that the staggering number should be a wake-up call for Washington.

In February, a statement from Puerto Rico’s government described the island as “the under-protected front in the nation’s war on drugs.”

After this week’s airport raid, officials in the commonwealth renewed their rallying cries.

“We have been asking the federal government to help us patrol…the Puerto Rican coasts, which we are unable to cover entirely by ourselves,” Gov. Luis Fortuno said Wednesday. “We want them to help us protect it in the same way they protect the borders with Mexico and Canada.”

On a national level, some lawmakers have taken note. A congressional hearing to discuss the situation is scheduled for later this month.

“The disturbing increase in drug trafficking and drug-related violence in this region…is alarming and unacceptable,” Michael McCaul, a Republican congressman from Texas who will chair the June 21 hearing, said in a statement. “If this kind of violence were happening anywhere else where 4 million American citizens resided, it would make daily headlines. This problem is no less serious than drug cartels operating across the Mexican border.”

Facing ‘widespread fear’

A group of gunmen burst into a bar on its opening night, spraying bullets at a crowd of revelers. Their target was a rival drug trafficker, authorities said, but eight bystanders were killed, including a 9-year-old girl caught in the crossfire.

The official death toll included a pregnant woman’s 8-month-old unborn child, who was shot in the head, CNN affilate WAPA-TV reported.

The October 2009 massacre in Toa Baja, Puerto Rico, marked a turning point.

It was the first high-profile example of criminals opening fire on a crowd with little regard for collateral damage, according to a report from the National Drug Intelligence Center.

“Violence by drug traffickers in the region has become indiscriminate, endangering the lives of public housing residents and innocent bystanders,” the 2011 report said, describing “widespread fear among the general population.”

It’s a feeling that makes people dread going out in the street, says Luis Romero.

“You could be walking, and all of a sudden – dah da dah da dah da dah – you hear these machine guns going off, and you get hit. And you were an innocent bystander,” he says. “And all of a sudden, you are a statistic.”

The 59-year-old telecommunications company CEO didn’t used to dwell on such details. That changed last year, after his 20-year-old son, Julian, was stabbed to death on a San Juan street.

Now Romero is president of Basta Ya PR, a nonprofit that has created a smartphone application to help the island’s residents report crimes to police.

In English, the group’s name means “enough already,” representing its efforts to promote community action and stop the surge in violence.

But there’s one thing that Romero says there isn’t enough of in Puerto Rico: funding from the U.S. government for the fight against drug trafficking.

Federal agencies on the ground, he argues, don’t have the tools they need to combat the growing problem.

“It’s shameful, the neglect of Puerto Rico,” he says.

A new avenue?

Drug trafficking is not a new problem for the island.

Puerto Rico’s strategic geographic location between South America and the continental United States has long made the commonwealth a central drug transit hub, says Laila Rico, a spokeswoman for the Drug Enforcement Administration.

Up to 80% of the drugs that pass through Puerto Rico end up in cities across the eastern seaboard of the United States, officials say. And nearly a third of drugs destined for the continental United States pass through the Caribbean.

Puerto Rico’s Luis Munoz Marin International Airport – the site of Wednesday’s raid – is “a major gateway for cocaine and heroin transported” to the continental United States, according to a 2011 report from the National Drug Intelligence Center.

Because Puerto Rico is a commonwealth of the United States, passengers from there don’t have to go through customs upon arriving on the mainland.

But some analysts say a new trend may be pushing even more cargo containers, fishing boats and yachts with hidden compartments toward Puerto Rico’s shores from South America (often by way of the Dominican Republic).

Faced with increased security at the Mexico-U.S. border, cartels may be searching for other trafficking routes, some analysts and officials speculate.

“If you attack one front, if you put your resources there, they search for other avenues, and the Caribbean is one of those avenues,” says Pedro A. Velez Baerga, an attorney and former deputy U.S. Marshal in Puerto Rico.

That’s a case that Pedro Pierliusi, Puerto Rico’s resident commissioner in Washington, has made for months as he’s pushed for a “Caribbean Border Initiative,” similar to efforts to fight drug trafficking along U.S. borders with Mexico and Canada, calling for a boost in resources and personnel to match “the scope and severity of the drug-related violence.”

Since 2008, the United States has pledged $1.6 billion in aid to Mexico as part of the Merida Initiative, aimed at helping Mexico combat cartels and organized crime. In that same period, Puerto Rico has received roughly $260 million to fund various addiction recovery, police and judicial programs, according to a recent estimate using government figures.

But some have cautioned against placing too much emphasis on law enforcement, who are often accused of corruption and abuse in Puerto Rico.

In 2010, an FBI investigation into whether police provided protection for drug dealers led to the arrest of 89 law enforcement officers in Puerto Rico.

And a September U.S. Justice Department report said that the Puerto Rico Police Department had a long pattern of violating citizens’ constitutional rights through excessive force and unwarranted searches.

Low public trust in Puerto Rico’s police, fueled by a troubling history of abuses by law enforcement, makes it harder to stem the violence, said Jennifer Turner, a human rights researcher at the American Civil Liberties Union.

“They are confronting a serious public safety crisis, but the problem is that, instead of limiting the violence, they’re contributing to the violence. … The police department uses the public safety crisis as an excuse for the abuses they’re committing,” she said.

Puerto Rico’s governor has said he is working with officials to reform the police department. He appointed a new police superintendent in March.

“The problem can’t be controlled only with policing measures,” says Jorge Rodriguez Beruff, a professor at the University of Puerto Rico who has researched drug trafficking in the region.

More economic and social programs are just as important to solving Puerto Rico’s drug problems, he says, which also include a significant population of drug addicts and far-reaching criminal networks.

Analysts once calculated that there were nearly 100 criminal organizations that were connected with drug trafficking in Puerto Rico, he says.

“It is an enormous business. We are talking about a business that possibly is bigger than the amount of tourism coming in to Puerto Rico,” he says.

A flourishing underground economy

Drug traffickers have a fertile recruiting ground in Puerto Rico, where unemployment has been hovering around 15%, and labor participation is around 40% (meaning 4 out of 10 people work), according to the Department of Labor.

“Having lost their direct employment, many people turn to working in the informal economy,” says economist Gustavo Velez, who describes drug-trafficking as a “significant component” of Puerto Rico’s underground economy.

“It’s a public policy challenge that is impacting the country’s security,” he said.

Little research has been done to study the underground economy’s impact on the residents of Puerto Rico’s more than 330 public housing projects, says Lilian Bobea, a sociologist and professor at the Latin America School of Social Sciences in the Dominican Republic.

“We are talking about communities that are basically living from informal work,” says Bobea, who has studied similar neighborhoods in the Dominican Republic and will begin a fellowship researching Puerto Rico’s public housing projects in the fall.

Leaders at drug distribution points inside the projects often pay children to move drugs, according to the National Drug Intelligence Center’s 2011 report on Puerto Rico.

Romero, the president of Basta Ya PR, says that reality is painfully clear when he speaks with children as part of his advocacy work.

“If you’re a drug runner you get paid $500 a day. Why would that guy want to go to school? … They know that they’re gonna die young, but they’re gonna take care of their mom with a lot of money. That’s what happens when you allow this sort of problem,” he says.

A 10-year-old boy told Romero he wanted to grow up to be a drug lord’s triggerman.

Journalist Dania Alexandrino and CNN’s John Sepulvado contributed to this report.