Tune in to the new CNN Original Series “Pope: The Most Powerful Man in History” at 10 p.m. ET/PT Sundays.

They were there to see the Pope: the students waving flags, the newlyweds in white, the priests and nuns and rich donors. In front sat the elderly and sick, many in wheelchairs: the Pope’s VIPs.

I watched from a balcony, like Zacchaeus in the sycamore tree.

As Francis approached the wheelchairs, a dark-haired man slowly uncoiled to meet his embrace. Francis touched the man’s head, blessing him, said a few words and moved down the line.

Moments later, a small boy leaped from his chair to hug Francis. His mother wiped her hands on her pants before shaking the Pope’s.

I was surprised to find my eyes tearing, accompanied by a short burst of benevolence. I felt a brief urge to hug everyone in the room. (I am not a hugger.)

Covering my tears’ tracks, I turned to a colleague. He was emotional, too.

It wasn’t the first time I’d felt like this. But still, it was a bit odd. Why would witnessing a moment of kindness between complete strangers move me to tears? Isn’t blessing people what popes and other holy men and women are supposed to do?

When I returned home, I emailed a journalist who has covered popes for more than 20 years.

“Those events never fail to move me,” he said. “They always seem to be the most authentic moments of papal activity.”

At least I wasn’t alone. But the question remained: What was going on in my brain?

Answering that question was tricky. I asked moral philosophers, psychologists and spiritual leaders. I scoured books and academic journals and online articles.

In the end, I learned that the sentiment I felt may be more common than you think, and it can be very contagious.

A few years ago, the Pope spread it to a Pennsylvania family, who infected a famous Hollywood director, who responded with a remarkable act of generosity, a karmic chain whose repercussions still ripple through the world.

Psychologists call the emotion “elevation,” and this is the story of what it does to us, whether you are Pope Francis or J.J. Abrams or Thomas Jefferson.

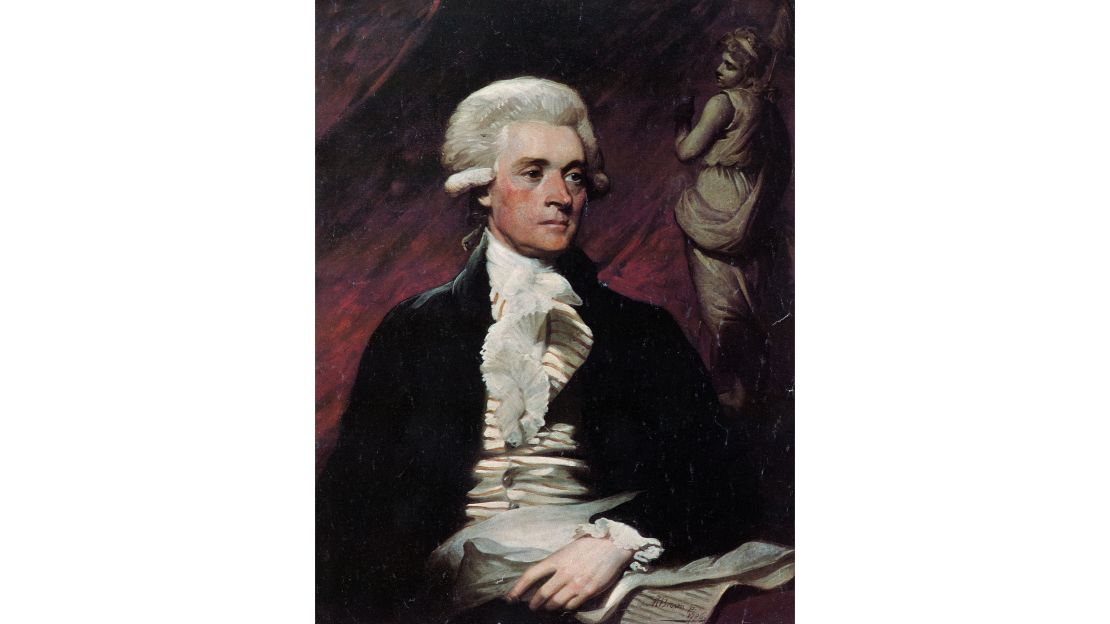

Yep, the man who “discovered” the feeling that makes us verklempt was the third president of these United States.

A presidential psychologist

Jonathan Haidt was sick of studying negative emotions.

For eight years at the University of Virginia, the social psychologist had been plumbing the depths of disgust, studying ancient moral codes and conducting modern experiments.

The idea of “positive psychology” attracted Haidt, who wanted to learn how to harness the power of emotions for moral growth, to help us live fulfilling and ethical lives.

One day, Haidt writes, he came across a letter written by Jefferson more than 200 years ago. In it, Jefferson describes the effects of observing moral beauty, even in works of fiction.

“When any … act of charity or of gratitude,” he wrote, “is presented to our sight or imagination, we are deeply impressed with its beauty or feel a strong desire in ourselves of doing charitable or grateful acts also.”

Observing good deeds, Jefferson continued, can “elevate” our bodies and minds, opening our chests and hearts.

The letter struck Haidt like a religious revelation: the sheer serendipity of finding a “new” emotion almost perfectly described by a former American president, at the very school that president had founded.

Jefferson had noted four major components of the emotion: a triggering event (you witness moral beauty), a physical sensation (your chest dilates), a motivation (you want to help others) and an emotional feeling (you are uplifted and optimistic).

That sounds a lot like psychologists’ current definition of elevation: a warm, uplifting feeling that we experience when we see unexpected acts of kindness, courage or compassion. It often makes us want to help others and become better people.

Haidt briefly considered calling the emotion “Jefferson’s emotion,” but thought better of it. Instead, he called it “elevation.”

Studies conducted in India, Japan and elsewhere have documented elevation, though people there may have different words for it. And religions have been telling elevating stories about selfless heroes for centuries, through texts such as the Bible or the Bhagavad Gita, a classic of Hindu literature.

Haidt, who now a professor at New York University’s school of business, began publishing his first academic papers on elevation in the early 2000s. Scholars from around the world soon followed suit, conducting experiments to test his theories.

“It’s a very unusual emotion,” said Simone Schnall, director of the Body, Mind and Behaviour Laboratory at the University of Cambridge. “To be honest, I didn’t think it would be something that people experience very often.”

But once she started studying elevation, Schnall says she started seeing it everywhere: on television, in daily life, while watching the Pope wash the feet of Muslim inmates on Holy Thursday.

“It’s not just feeling good,” says Schnall, who has co-written three academic papers on elevation. “It compels you to want to do something.”

But some psychologists say Haidt has missed the mark on elevation. They argue that what I felt in Vatican City is actually a different emotion, with a different name.

The earth got goose bumps

Kama muta.

That’s what Alan Page Fiske, an anthropologist at UCLA, calls the emotion that washed through me when I saw the Pope blessing the elderly and the sick.

The phrase means “moved by love” in Sanskrit. (The more well-known phrase kama sutra roughly translates as “love book.”)

Fiske says the closest we can come to the meaning of kama muta in English are words such as moved, touched, stirred or smitten. Christians might say that they’ve been slain in the Spirit or rolled by the Holy Ghost. Sufis might feel it during mystical moments, other Muslims on the Hajj pilgrimage. Mormons might call it “burning in the bosom.” In internet slang, it’s the stuff that makes you feel all the feels.

What connects those words is a feeling of oneness with another person or being, Fiske says. Kama muta is primarily a communal emotion; it bonds us to each other, makes us feel “cozy and connected.”

Researchers have studied kama muta in 19 countries, showing participants videos of cute kittens, families reunited after long separations, or people being kind to strangers.

“All evoke kama muta,” Fiske says. “Because they depict a sudden intensification of a communal relationship.”

What I felt was kama muta, too, according to Fiske.

“Your emotional reaction is just the one that observers are said to have felt when observing the Buddha, in his past avatars, performing extraordinary acts of loving kindness,” Fiske told me. “In the ancient Pali texts such acts are said to give observers – and even the earth itself – goose bumps.”

Like elevation, kama muta often comes with both physical and moral components, Fiske said. We feel flushed or get goose bumps and want to be kind and loving, whether that means calling our grandmother or helping a friend. Also like elevation, kama muta is a relatively new academic discovery. We still have a lot to learn about it.

Academics seem to know a little more about elevation, including lab experiments that show just how much power the emotion can have over us.

Transcending the self

In 2016, two scholars examined the empirical evidence on elevation for the American Psychological Association’s academic journal. The results were extraordinary.

Experiments had found that elevation made people more likely or willing to volunteer for onerous tasks, donate to charity, mentor other people, register as an organ donor and cooperate with others.

In other experiments, elevation was found to reduce prejudice and negative attitudes toward “outgroups” such as LGBT people and African-Americans. One experiment even found initial evidence that elevation could lead nonreligious people to become more spiritual, mainly by fostering a sense that people are benevolent and life is meaningful.

“Elevation appears to lead to transcending the self – psychologically, physiologically and behaviorally,” wrote the scholars who summarized the findings on elevation, Rico Pohling of Germany’s Technische Universitat and Rhett Diessner of Idaho’s Lewis-Clark State College.

“Therefore, it may help us to connect with each other, to temporarily overcome our selfishness and perhaps to move toward changing ourselves and thus inducing an upward spiral of positive change, not only for the individual who experiences it, but for a whole community.”

But elevation may not be all kindness and connection, Pohling and Diessner warned. One study found initial evidence that suicide bombings could cause elevation “within members of the same cultural group.”

“The results exemplify that elevation may indeed foster a desire to become like a martyr in certain societies,” the scholars wrote. “However, further studies are needed on this highly provocative topic.”

Most of the studies, though, offered empirical evidence about elevation’s potential benefits. Here’s how one worked:

In 2010, three scholars set out to test if elevation could inspire altruism in British university students. They recruited 59 young women from the University of Plymouth in England and broke them into three groups.

One group was shown a video clip of Oprah Winfrey’s show in which musicians expressed appreciation for their mentors. Another was shown a sketch from “Fawlty Towers,” a British sitcom, intended to produce mirth. The control group saw a nature documentary.

After watching the videos, the women were asked to write a short essay about what they had seen, while the researchers pretended to have computer problems that fouled up the whole experiment.

Would the women be willing to participate in another study, the researchers asked, warning that it was “rather boring” – a series of 85 elementary math questions.

The women who had seen the Oprah clip, the researchers found, not only felt elevated – warm in the chest, uplifted in the mind – they were more likely to volunteer for the boring study and spent roughly twice as much time on the math questions as the women who had seen the comedy or documentary. Many even stayed to help beyond the hour for which they had signed up, the researchers said.

Daniel Fessler, an evolutionary anthropologist at UCLA who co-wrote the study, said we don’t fully understand elevation yet. We don’t know why we feel it, or why, from an evolutionary perspective, feeling it would offer an advantage to a particular person.

But the societal effects of elevation could be huge, Fessler and other scholars said.

The study of elevation could help nurses, doctors, social workers, teachers and others who work long and often under-appreciated hours caring for other people.

It could also reshape how we teach ethics and morals to students. They might, for example, be interested in a real-life example of altruism that stars a famous Hollywood director.

A famous case of elevation

Kristin Keating was sitting in a movie theater when she began to cry. A preview for a new documentary on Pope Francis had begun to play.

“Everything came flooding back,” she said.

In 2015, Keating, her husband, Chuck, daughter Katie and twin sons Michael and Christopher were on the tarmac at Philadelphia International Airport when Francis arrived for the World Meeting of Families.

The marching band Chuck Keating leads at a Pennsylvania Catholic school had been selected to play for the Pope as he disembarked from the plane. (They chose the theme song from “Rocky,” of course.)

Just as the Pope was driving away from the airport, he or someone in his entourage spotted Michael Keating, who has cerebral palsy and uses a wheelchair. The Pope asked his driver to stop the car, slowly walked to the Keatings, leaned over a guardrail and planted a kiss on Michael’s head.

“It would have been very easy for him to bless Michael without getting close to him,” Kristin Keating said. “But he put in a lot of effort. It speaks to who he is.”

“It was uplifting for all of us,” added Chuck Keating, “to know that someone was looking after us.”

Kristin remembers peering at the Pope through tears, then shaking a hand that felt soft as a cloud.

“You know how people say that something wonderful will get them through the rest of the week? I felt like the Pope’s blessing will get me through the rest of my life.”

The emotion the Keatings felt probably wasn’t elevation, experts say. It was gratitude. Elevation is when we’re moved by good deeds done for others; gratitude when the deeds are done for us.

A video of the Keatings’ moment with the Pope, which lasted less than 90 seconds, went viral. The Washington Post followed up with an article detailing the sacrifices Chuck, Kristin, Katie and Christopher have made to care for Michael. Kristin has already had two hernia operations from lifting Michael.

The Washington Post article caught the attention of J.J. Abrams, the co-creator of “Lost” and director of Hollywood blockbusters such as “Star Trek” and “Star Wars: The Force Awakens.”

Abrams was so moved by the Keatings’ story that he and his wife immediately donated $50,000 to the Pennsylvania family. And Abrams wasn’t alone. More than 650 people gave the Keatings nearly $100,000.

The donations were a godsend, Kristin Keating said. The family used the money to buy a van that could accommodate Michael’s wheelchair, which means her days of heavy lifting may be over.

Abrams told The Washington Post that he and his wife, Katie McGrath, made the donation “likely for the same reason others did: We were moved by the Keating family’s grace, strength and commitment to each other.” (Abrams’ agent did not immediately respond to a request for comment for this story.)

The Keatings say they’ve tried not to make their house a shrine to Michael’s moment, but they have kept reminders of the day the Pope singled their family out: tote bags full of newspaper articles, a DVR half-full of news reports, rosary beads from the World Meeting of Families, tumblers adorned with the image of Francis kissing Michael’s head.

The Pope seems keenly aware of how many lives he can touch with simple gestures. He’s done it too many times for it to be a coincidence: embracing a man covered with boils, washing the feet of inmates, personally escorting refugees to Vatican City, or the example that moved me, the simple act of paying attention to sick and elderly people.

Those moments speak volumes about the moral power of the papacy, but they also say something about us. We are hungry for such moments, even captivated by them; we want to rush off and tell others about what we’ve seen and, afterward, we want to become better people.

It’s not a new thing under the sun, but maybe each generation needs to learn the lesson again: Edicts and rules may keep us from behaving like devils, but if you want us to be saints, it helps to show us how.