On the side of a building just outside the county jail in Des Moines, Iowa, there is a drive-thru window. But it is not dishing out burgers and fries. The main item on its menu is freedom, and it can come at a steep price.

“Get your bail bond here. Don’t wait at jail,” reads the old-timey script on a sign in the yard.

The unassuming tan building with green and burnt orange accents sits on a small hill before the jail. There is no way to miss Lederman Bail Bonds on the way in or out of the correctional complex.

It’s the family business – run by four brothers who have operations across Iowa and the rest of the Midwest. But behind the familiar drive-thru window set up is a well-funded political force with an agenda to stop the jail at the bottom of the hill from making any changes to a bail system that keeps their profits rolling in.

Across the country, bail bond companies like the ones owned by the Ledermans are up in revolt, fighting back against states’ efforts to rethink and overhaul an antiquated money bail system.

Corrections officials, jail runners, judges, public defenders, civil rights groups, and bipartisan leaders alike agree that the system in place that handles the presumed innocent is broken.

As structured, the bail bonds industry survives largely off those who don’t have the financial resources to post bail. Overwhelmingly, the service of a bail bondsman is their only way out of jail. Bail bond companies make money by charging a fee – typically 10% of a defendant’s bail amount. So if a defendant has bond set at $50,000, the bail bond company charges $5,000 to get them out. No matter what, the bonds company will collect that charge – guilty or not guilty. Even if the charges are dropped. That is the price and process of release.

Those who can’t afford the 10% the bond company charges can set up a payment plan, usually in small installments like $100 a week until the big bill is paid off. Contracts like those tether vulnerable families to debts that can linger on for years – landing them in court for missed payments, with garnished wages and accruing interest. Experts say defendants will sometimes plead guilty to lesser charges, even if they are innocent, in order to avoid the bail system and get out of jail sooner.

More affluent defendants, who can afford to post bond with their own money, go free and get the money back provided they show up for their court dates.

Reform efforts across the country seek to make the bail system less burdensome on the poor. The majority of states addressing the issue are trying to make money bail the last resort, by mandating that judges apply the “least onerous release conditions possible” and consider the defendant’s ability to pay, as well as eliminating money bail for low-level charges. As a result, the $2-billion-a-year bail bonds industry is in a fight for its very survival.

A CNN review of all 50 states and the District of Columbia found that the powerful industry has derailed, stalled or killed reform efforts in at least nine states, which combined cover more than one third of the country’s population.

To date, more than 25 states have passed laws or enacted changes that address bail practices, while several still have pending efforts or bail procedure review committees in the works.

The story of bail reform is as messy as it is laborious. It’s a long road of continuous push and pull between stakeholders. Even among reformers, there’s disagreement over how best to do it. A popular remedy is using some sort of computerized “risk assessment” tool that evaluates the likelihood a person would show up for court based on criteria such as age, past failures to appear for court and criminal convictions. However, some scholars and civil rights activists, including the ACLU, oppose such tools, saying they are flawed and often racially biased.

Whether attempting sweeping or modest change, lawmakers have described the bail industry’s involvement as nasty and contentious.

Jeff Clayton, the Executive Director of the American Bail Coalition, said that the process is tense on both sides and that his industry is unfairly being called predatory.

“We don’t arrest the people,” Clayton said. “We don’t set their bails. And if people want to use our services, we feel that’s an extension of their constitutional right to do so.” Clayton adds that while his group “participated in public policy discussion regarding bail reform” in the nine states outlined by CNN, “we definitely had significant impact” but “I don’t think we were the driving force.”

Even after a reform is passed, the battle can continue.

Last year, California lawmakers passed the most far-reaching legislation yet – ending cash bail altogether. But shortly after the passage of that law, the bail bond industry, and the insurance companies that underwrite their bonds, raised more than $3 million to fund a ballot referendum that put everything on hold. The effort was successful, and voters will decide the issue on the November 2020 ballot.

The same thing is happening across the country.

In Texas, for example, there was a clamor for reforms following the jailhouse death of Sandra Bland, who had been arrested for allegedly assaulting an officer during a July 2015 traffic stop for not using a turn signal. Her family was working to secure the 10% fee to hire a bondsman on her $5,000 bail, but three days after her arrest she was found hanging in her cell. Had Bland been able to afford her bond, reformers say, she would not have sat alone in a jail cell for three days.

Texas tried to pass reforms in the 2017 session, but the bail industry’s lobbying efforts helped thwart the measure from progressing, according to a committee staff member. This past session, despite even wider support and a strong initiative by the governor, bail reform died again, as the bill the House passed was never put on a Senate committee calendar.

Most lawmakers pursue bail reform because of the consequences that come with putting a price on someone’s freedom, particularly if that person is poor.

County jails are overflowing with people waiting to have their day in court. They far outnumber those who are serving actual sentences for crimes.

Cherise Fanno Burdeen, who runs the Pretrial Justice Institute, an organization that has fought for reform for over four decades, likens the bail system to a “ransom.” And for those who can’t pay, she said, the toll of remaining in jail until trial can be devastating. They might lose a job, which, in turn, could mean rent won’t get paid, families won’t be fed and so on. It’s particularly troubling for people accused of nonviolent or relatively minor crimes, she added.

“Low-risk people who can’t afford to post bond spend days, weeks, months in jail until they take a plea or their cases are actually dropped,” said Burdeen. “It has a dramatic impact on people.”

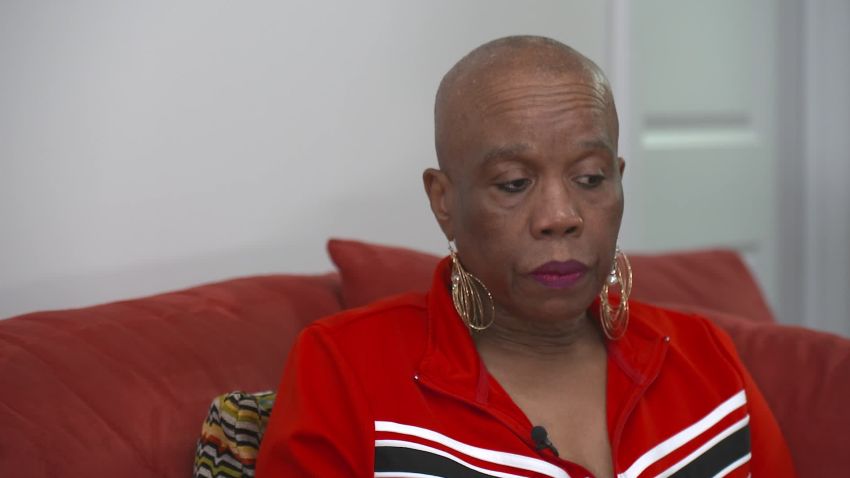

Alice Hughes’ experience with a bail bonds business meant she had to come out of retirement and find a job.

It started with a phone call from her nephew, who was arrested on drug charges and violating a protective order and wanted her to help bail him out of a Baltimore jail. His bond was $75,000. Hughes said she did what anyone in her position would do. She took all the cash she had, $700, and brought it to a bail bonds shop across from the jail. The money didn’t come close to the $7,500 charged to get her nephew out. So she co-signed paperwork setting up a payment plan for the rest.

“Normally, I check things out before I do them. I read everything,” Hughes told CNN, “but in this instance, all I was thinking about was getting him out.”

Hughes’ nephew did get out, and he was released on bail, but failed to keep up with the payments to the bond company. Before Hughes knew it, the company went after her.

And the debt kept getting bigger. The court ordered wage garnishment for her to chip away at the debt.

Her biweekly paycheck from the retirement community she works at has $131 taken from it and given to that bond company. Because of accruing interest, she says, she may never be able to pay it off. At the time of her case’s judgment she owed $8,690. Hughes’s attorney has filed a motion to have the garnishment end, and she is part of a putative class-action lawsuit that alleges the bail company was operating without a license. The parent company says it was licensed, but she was dealing with an unlicensed entity. The court has denied two motions to dismiss.

Maryland’s highest court adopted a rule in 2017 that requires judges to consider defendants’ ability to pay for their release, among other aspects. But the change came too late for Hughes and her nephew, who was arrested in 2014.

It can take years to fully measure the effectiveness of reforms. But studies in several counties show their effort at overhauling the bail system have been successful at achieving two main goals: Making sure people show up for their court dates and reducing recidivism rates.

In Spokane County, Washington, a state auditor report found that “defendants released on pretrial services were much more likely to show up for their court hearings than those released on bail.”

Lucas County, Ohio, saw a 50% decrease in recidivism for those released on misdemeanor charges, according to a report by the National Association of Counties.

Results and practices such as those have prompted lawmakers to seek statewide reforms. In a handful of states such as Montana and New Hampshire, officials say they did not face heavy backlash from the bail industry when seeking changes. Seven states and the District of Columbia do not have a private bail bond industry. Instead, they have a mixture of options like allowing defendants to pay 10% of their total bond directly to the court, like they would through a private bondsman. But for nearly every other state considering reform, measures are challenged by the bail bond industry and its lobbyists.

That was the case in Iowa. And a good part of the resistance to reform measures there can be traced back to the owners of the hilltop bail bond drive-thru.

In a courthouse across the street from the Lederman’s bail bonds office in Davenport, Iowa, justice officials started a pilot program last year to ease the burden of bail on the poor.

Under the program, judges in four counties used a computerized risk assessment tool called the “Public Safety Assessment” to determine a person’s risk of failing to appear at court or reoffend if released.

The tool analyzes nine risk factors, including age, past criminal convictions and previous failures to appear. Judges were then given a defendant’s risk score to determine whether he should be released on his own recognizance, have some level of supervision or require a bond. Decisions were ultimately up to a judge.

The pilot program threatened the profits of the bail industry and Lederman’s family business. And Josh Lederman set out to do something about it.

Josh Lederman, one of the owners of Lederman Bail Bonds, began attending monthly public meetings for Department of Corrections where he questioned the merits of the pilot program.

Along the way, he opened up his wallet, giving more than $36,000 to Republicans, mostly those running for the Iowa state legislature, donating more in one year than he had in the past 15 years combined. Some of the candidates were running unopposed in their races.

But his biggest investment started in 2017, before the 2018 legislative session, when he began shelling out about $74,000 to date to hire a powerful lobbying firm in Des Moines.

The Lederman’s lobbying efforts worked, according to officials in the state justice system and Democratic state lawmakers.

Late in the legislative session last year, language to end the program was inserted into the Justice Systems appropriations bill which passed, killing the bail reform pilot program.

This came as a shock to many, including Democratic legislators who fought against the program-killing language.

“This was an unusual piece of legislation, stuck in a budget bill,” said Iowa state Sen. Tony Bisignano.

Another Democratic lawmaker said it all came down to money. “Lederman Bail Bonds didn’t like the program because there were defendants that were getting out of jail without having to post any type of a bond,” said state Rep. Rick Olson. “They were losing business.”

When the bill landed on Gov. Kim Reynolds’ desk, she used the line-veto to extend the program to run until December 31 last year, when it ultimately ended.

Lederman Bail Bonds did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

This session, the legislature had the opportunity to address the pilot program’s future. But the same language to forbid the use of the PSA tool was included in the same budget bill, and the program has been officially ended.

CNN has talked to over a dozen officials in Iowa – judges, corrections officials, public defenders, and legislators alike – who supported the bail reform effort and are now trying to figure out the next step in bail reform in their state.

Burdeen, from the Pretrial Justice Institute, believes that despite the bail industry’s efforts, there is momentum behind changing the bail system. “I think that there’s a real need for an awakening around fundamental fairness,” she said.

CNN’s Audrey Ash contributed reporting.