Editor’s Note: Diana B. Carlin is professor emerita of communication at Saint Louis University. She has researched political debates since 1980 and is the author or co-author of 15 articles and books on debates including “The 1992 Presidential Debates in Focus.” Mitchell S. McKinney is professor of communication and director of the Political Communication Institute at the University of Missouri. He is the author or co-author of nine books exploring political campaign communication, including “An Unprecedented Election: Media, Communication, and the Electorate in the 2016 Campaign.” The opinions expressed here are their own. Read more opinion at CNN.

It is unlikely that anyone would make a hiring decision without interviewing them, based only on some combination of the candidate’s resume, testimonials from family members, social media comments and scurrilous accusations from anonymous critics. That’s why we disagree with those who want to scrap presidential debates, the metaphorical equivalent of a presidential job interview.

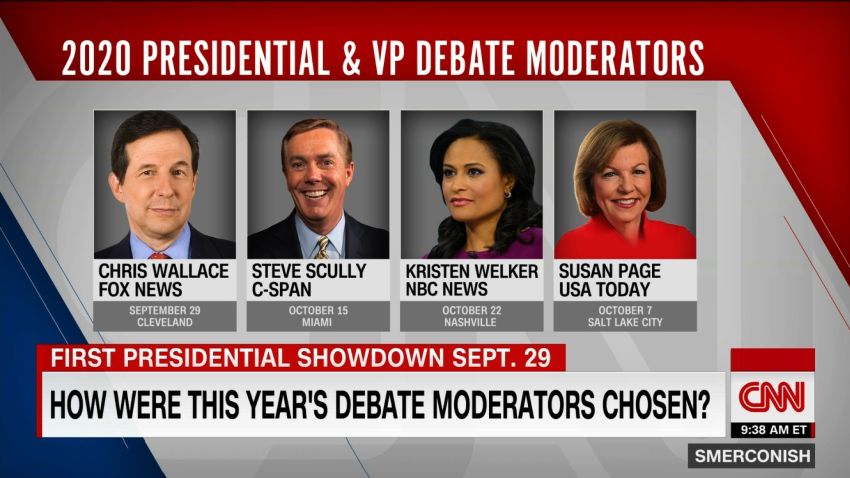

That metaphor is commonly used by focus groups we’ve conducted since 1992 to explain why citizens watch these events. And we expect voters will again want to watch the “interview” between President Donald Trump and Joe Biden on September 29 – the first of the three scheduled presidential debates ahead of the November 3 election.

Over the years, during the course of our research, we’ve heard many of the arguments for abolishing debates. The principal ones are that they don’t change votes, are not substantive, present no new information and encourage candidates to play for clever one-liners that get picked up by the media.

In the spirit of debate, we answer each argument here.

First, the objection that debates don’t influence the election outcome because they don’t change voters’ minds. In close elections such as 2000 and 2016, where narrow margins in one or a few key states determined the outcome, debates could make the difference. Exit polling from 2016, for example, showed that 21% of voters said Supreme Court appointments were “the most important factor” in their choice – the topic for the first 15 minutes of the third debate – with 56% of those respondents having voted for Trump.

In our view, they were among Trump’s most effective 15 minutes of the entire campaign. He reminded wavering Republicans after the uproar over his lewd comments in the “Access Hollywood” tape why they wanted a Republican in the White House.

Our research with pre- and post-debate surveys consistently shows that debates influence undecided and wavering viewers. It’s true that many voters use debates to confirm their vote choice, not to change it. However, in this election year, where the undecided group is small but millions of young Americans are eligible to vote for the first time, the debates could be crucial shaping new voters’ choices and deciding the outcome.

Then there’s the argument that debates are not substantive and present no new information. If true, that makes a compelling case for eliminating them. However, our research shows these accusations are not based on what debate viewers believe, but rather on what political pundits think. Viewers want debates and the numbers prove it. In 2016, two of the three Clinton-Trump match-ups set all-time debate viewership records, with the first drawing a total of 84 million viewers, per Nielsen data – the largest viewing audience in the history of televised debates that began with the John F. Kennedy-Richard Nixon encounter in 1960.

Many studies reveal that viewers gain important information from debates. Our reviews of hundreds of focus group transcripts since 1992 shows that every group had members who say they learned something new. Knowledge gained from debates by first-time and leaning, but not committed, voters increases confidence in their choice and may even influence their decision to go to the polls at all.

The town hall debate format, in particular, provides a way for voters’ agendas to be heard. Our research team’s analyses of both the content and effects of the town hall reveal several distinct benefits. Unlike some journalist-led debates, the questions asked by citizens typically mirrored issues cited as most important to the public. Candidates were usually less combative (although this was not the case in 2016) and more responsive to voters’ questions than they were to those from the reporters with whom they are more likely to spar or outright ignore. Town hall viewers also found this event more engaging and reported heightened political interest and decreased political cynicism following their exposure to a town hall exchange.

The last objection relates more to primary than to general election debates. The primary debates, especially those that took place during the 2020 campaign, were on commercial cable with multiple interlocutors and designed to elicit audience response and conflict among the candidates because the drama created is assumed to increase viewership and advertising dollars. There is no comparison between these and the commercial-free general election debates sponsored by a non-partisan group with private funding, a pooled feed and a single moderator. Yes, they both have audiences, but the general election debate audiences typically adhere to the request to not applaud or react to candidates’ one-liners.

The 2020 primary formats violated all good standards of political debates. They did not let each candidate respond on every issue and there were large time allocation differences among the candidates. As a result, primary debaters often did everything they could to get attention and air time. In the general election debates, the format provides an opportunity for candidates to respond to the same set of questions. With 15-minute segments typically devoted to only six issues in two of the debates and nine segments of 10 minutes each in the vice presidential debate, there is less need to interrupt and speak over the other candidate. If the media focuses on the drama and the one liners rather than the substance, then journalists – not the debates – are to blame.

Debates have been part of the US political scene since James Madison and James Monroe debated for a seat in Congress and Abraham Lincoln served as a surrogate debater for the Whig party in the days when presidential candidates did not publicly campaign.

Get our free weekly newsletter

Rather than scrapping time-honored debates – either primary or general – why not continue to improve them? The single moderator format is far superior to the panel; eliminating the audience is a reasonable way to end disruptions and using equitable formats and turning off the microphone of anyone but the speaker can reduce the food fight atmosphere. And this pandemic year has shown that a virtual debate with online questions from voters can easily replace the town hall.

Nothing about a democracy is perfect and nothing about political debates is perfect. But they remain, based on public opinion and solid research, the best way to communicate candidate positions and differences to the public.