Scientists have announced the discovery of 20 new species in the Bolivian Andes, as well as sightings of plants and animals not seen for decades.

Located near the Bolivian capital of La Paz, Zongo Valley is known as the “heart” of the region. High up steep, rugged mountains are an array of well-preserved habitats, which are thriving with lush biodiversity.

It was among the cloud forests that researchers discovered the “mountain fer-de-lance” viper, “Bolivian flag snake” and “lilliputian frog,” as well as glorious orchids and butterfly species.

The findings, revealed in research published today, were made on a 14-day expedition in March 2017, co-led by Trond Larsen of the non-profit environmental group Conservation International.

“[In Zongo] the noises you hear are from nature – all sorts of insects, frogs and birds calling, wonderful rushing sounds and cascades of waterfalls. Everything is covered in thick layers of moss, orchids and ferns,” Larsen tells CNN.

“We didn’t expect to find so many new species and to rediscover species that had been thought to be extinct.”

Venomous viper

The extremely venomous mountain fer-de-lance viper has large fangs and heat-sensing pits on its head to help detect prey. Previously unknown to science, since the expedition the viper has been found elsewhere in the Andes says Larsen.

The Bolivian flag snake earned its name from its striking red, yellow and green colors, and was discovered in dense undergrowth at the highest part of the mountain they surveyed.

Another discovery is among the smallest amphibians in the world, according to Larsen. The aptly named lilliputian frog is a minuscule 1 centimeter in length. With its camouflaged brown color and tendency to hide in thick layers of moss and soil, it’s almost impossible to spot.

“We followed the sound of them in the forest but as soon as you get near them, they get quiet so it’s tremendously difficult to locate,” says Larsen.

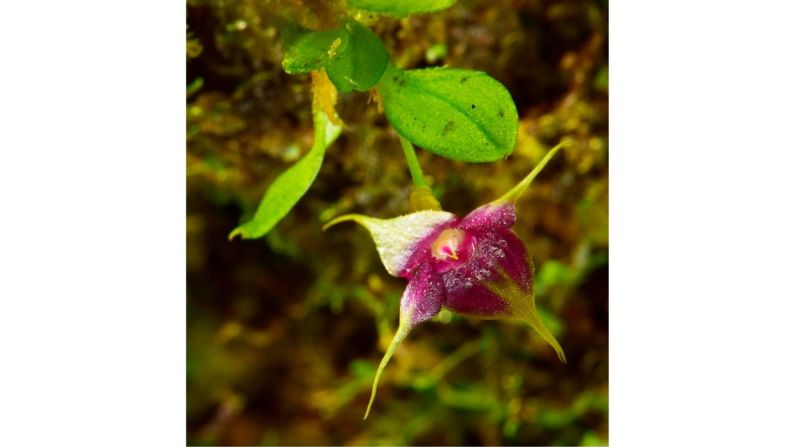

Zongo’s valley flourishes with orchid flowers varying in size, shape and color. The newly found Adder’s mouth orchid has parts that cleverly mimic insects, tricking them into transferring pollen.

Although the discoveries are new to science, they are familiar to local indigenous communities. A newly discovered bamboo has been regularly used by indigenous people for construction materials and to make wind musical instruments.

Devil-eyed frog

As well as identifying new species, the team rediscovered four species thought to be extinct, including the mesmeric “devil-eyed frog,” which is black in color with deep red eyes. It was last sighted 20 years ago, before a hydroelectric dam was built in its habitat. After numerous attempts to find the frog it was assumed the species no longer existed.

“Given that all these other expeditions failed we did not think that we would [find it] and when we did discover it, it was quite an epiphany, incredibly exciting,” says Larsen.

The satyr butterfly, last seen 98 years ago, was rediscovered in the Zongo Valley’s undergrowth, caught in a trap containing its food source of rotten fruit.

Forest corridors

Some of these animals may be found nowhere else in the world and Larsen says much of the region’s wildlife is having to adapt to the effects of climate change. Many species are moving to higher ground in search of cooler conditions, traveling through forests that lead up into the mountains.

“Unless you keep those corridors of forest intact then those animals and plants have no way to move and no way to adjust to those changing conditions,” explains Larsen. “That’s why protecting places like the Zongo is so essential in the face of climate change.”

As well as being a haven for wildlife, the area is also key for people living nearby. Locals depend on the forests for building materials, says Larsen, while Zongo supplies hydroelectric power and water for La Paz and beyond.

Conservation International says the findings make the case for the protection of the area and will help inform sustainable development plans for the region.

“The importance of protecting the Zongo Valley is clearer than ever,” said Luis Revilla, mayor of La Paz, in a statement. “As La Paz continues to grow, we will take care to preserve the nearby natural resources that are so important to our wellbeing.”