In order for the incredible array of discoveries made by scientists each year to be shared with the rest of the world, they must be communicated in an understandable way.

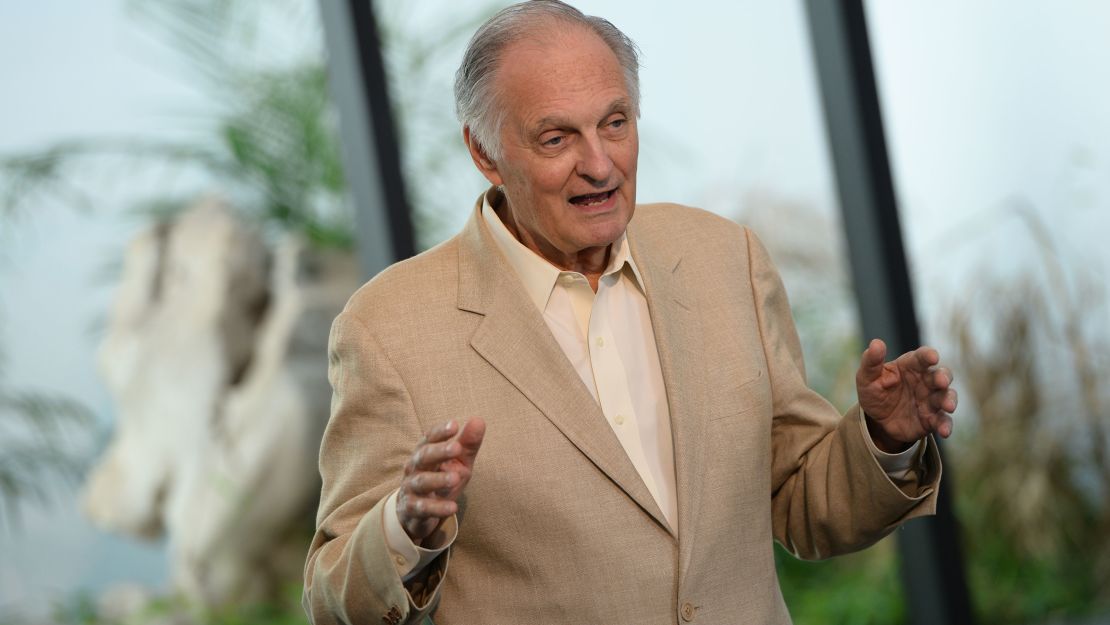

Nobody finds more awe or joy in that task than Alan Alda, whose latest project shines a light on how Dr. Anthony Fauci and other physicians revolutionized American medicine at the National Institutes of Health during and after the Vietnam War.

Many associate Alda with his beloved character Capt. Benjamin Franklin “Hawkeye” Pierce from “M*A*S*H” or his film roles – but science and curiosity have been intertwined with his life from an early age.

Alda recalled observing the adults around him when he was only 3 or 4, “trying to figure out what they meant by what they said,” he told CNN.

“And then when I was about 6, I was doing experiments on a card table where I tried to mix my mother’s face powder with toothpaste to see if I could get it to blow up,” Alda said. “When I was 10, I was an amateur inventor who would make drawings and models of my inventions.”

As a young actor in his early 20s, Alda discovered the magazine “Scientific American” and was “introduced to a whole new way of thinking, which was interesting ideas but with evidence to back them up. And then I was hungry for it. I couldn’t get enough of it. “

When Alda was asked to host the PBS show “Scientific American Frontiers” in 1993, he jumped at the chance to chat with scientists all day long, Alda recalled. He accepted under one condition: That he wouldn’t just host the show but interview the scientists as well. An agreement was struck and Alda hosted the show for 14 years until it ended in 2005.

Alda became a visiting professor at Stony Brook University in New York and founded the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science there in 2009. The Center uses improv and other unique storytelling methods to help scientists better share their findings.

And Alda’s love affair with science has continued.

The Soldiers of Science

Alda’s latest project, an Audible Original podcast, releases on Thursday. It’s called “Soldiers of Science: The untold story of the Vietnam War, Anthony Fauci, and a generation of doctors who revolutionized American medicine.”

And it couldn’t be more timely. The podcast, written by Alda and Kate Rope, and narrated by Alda, tells the forgotten story of the doctor’s draft that brought a new generation of physician scientists to the National Institutes of Health.

That group includes a familiar name: Dr. Anthony Fauci. And the so-called “yellow berets” worked on breakthroughs in American medicine that would save lives, like creating the first statin. Their research led to nine different discoveries that each earned the Nobel Prize.

“It was a moment that actually changed the history of medicine in this country, not just in the development of medicines, but the research labs and universities all over the country,” Alda said. “It was a fountain of innovation and a way of working that was collegial.”

Fauci told Alda that a breakthrough they had in the development of a treatment for an autoimmune disease came from conversations with physicians in other disciplines when they were in the cafeteria.

Fauci and other scientists in the program, as well as the patients they helped, join Alda in the podcast. In addition to telling stories from the past, they share their hopes for a future program that combines science and service, to shape the next 50 years of breakthroughs.

The podcast, a celebration of a time when a firm belief in the power of science led to the innovation of American medicine, comes at a divisive time in our country nine months into a pandemic. It’s also a time where people seem divided into two camps when it comes to trusting science.

“We’re in a technological bumper car where people are hearing the same misinformation that they already believe and not hearing any other information,” Alda said.

His hope for the future of science communication is much as it was 11 years ago when he began his center at Stony Brook, only more intense.

“Let it be communicated clearly and vividly so that it engages us and that we learn from it,” he said.

The science of improv

When “Scientific American Frontiers” came to an end, Alda began to think about how to capture that intersection of science and storytelling in another way.

“Wouldn’t it be great if we could train scientists to have this connection that we had on camera?” Alda said. Before hosting the show, Alda didn’t have much experience interviewing people. He relied on the techniques he had picked up from improvising – the only acting technique he ever studied.

His concept: training scientists on improvising and producing a message based on personal connection.

Whenever Alda was at universities for speaking engagements or events, he would bring up his idea of training students to be scientists and good communicators at the same time – both to the general public as well as policymakers and even their own colleagues across fields. Stony Brook University had a positive response to his idea.

In 11 years, Alda’s center has trained 15,000 people across the US and in eight other countries. The center offers courses as well as workshops and has transitioned to offering online classes amid the pandemic.

One of the improv exercises Alda and the center’s teaching staff uses early on in the program is a technique called mirroring. Two partners face each other and one mirrors the slow movements of the other. Moving slowly allows your partner time to catch on to the movements. It builds a connection between the two people so they can read and anticipate each other. Eventually, it’s hard to tell who is the leader and who is the follower.

Teaching at the center helped Alda realize how important it is for scientists from different fields to communicate with each other. In recent years, scientific breakthroughs have been the result of collaboration across fields – and that will only continue in the future.

But by talking to one another, scientists can also step back from the details of their individual work to see how it connects with the work of others and identify the bigger picture.

Courses and workshops at the center also deal with the issues that female scientists may encounter in their fields or when communicating with others.

Recognizing that power imbalances and rigid hierarchies exist in these fields is the first step. The next is learning techniques through role playing to fix that power imbalance, Alda said.

Science: A detective story

When Alda talks to a scientist, no matter their discipline, he wants to understand the drive behind what they do.

“We try to open up the spigot so that passion comes out,” he said.

It’s the human side of science storytelling that can lead the audience to learn more about a discovery even if science doesn’t appeal to them.

Growing up as the son of a father who performed in burlesque theaters, Alda was witness to the reality behind the illusions on stage by standing in the wings. He saw where the magician hid the pigeons. But he also saw both sides of the story unfold – and how the performers connected with their audience.

“You don’t need to call it science, you just need to tell them really fascinating stories,” he said. “Science, on the one hand, is the most captivating detective story ever told. And there are many aspects of scientific discovery that can be told just like a detective story. What’s this mysterious thing happening, who’s the villain, what’s causing it?”

And science itself is a puzzle. Some scientists spend their whole lives fascinated by one piece among thousands. But if they were to walk out on the stage of an auditorium and dump the pieces on the floor or hold up one piece at a time, it doesn’t captivate the audience. But a finished puzzle that connects everything together does, Alda said.

Alda is the host of two podcasts, “Clear + Vivid with Alan Alda” as well as “Science Clear + Vivid.” This year on “Science Clear + Vivid,” the series focused on basic science. But next year, Alda is excited to focus on breakthroughs and young scientists eager to discuss their work.

If it were possible to bottle his joy about science and the discoveries that have changed so much of what we understand, the world would be a better place. But, as he humbly puts it, Alda does what he can with the tools he possesses.

When asked if he was partial to any particular field within science, Alda smiled. He’s driven by curiosity and an endless love of learning and listening – the same motivations that drove him as a young child.

“It almost doesn’t matter what work the scientist does, as long as they have that quality that most scientists have, which is eagerness to know more about their own field, and an equal eagerness to share it with somebody else,” Alda said. “They have this wonderful knowledge that’s hard to keep to themselves. And it’s great to help them get it out. I really love it.”