Editor’s Note: James Goodman, distinguished professor of history at Rutgers University, Newark, is the author of “Stories of Scottsboro,” “Blackout” and “But Where Is the Lamb?” The views expressed here are his own. Read more opinion on CNN.

A modest proposal: It’s time to stop calling slavery America’s “original sin.”

There is no need for me to name names. So many people do it. Secular people as well as religious people; lay historians as well as men and women of the cloth; rabbis as well as ministers and priests; people who believe that Adam and Eve’s disobedience resulted in their expulsion from paradise and the estrangement of human beings from God, and people who have never given the Fall and its consequences a moment’s thought; left-wingers, right wingers and just about everyone in between. It is one of the few things about which longtime political opponents Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell and former President Barack Obama agree: Slavery was America’s original sin.

The habit might seem harmless, shorthand for saying that slavery was distant, deeply embedded and bad. All history is hindsight. We often see things that people couldn’t or didn’t see at the time. We tell stories and offer interpretations that depend on our knowledge of events that happened between then and now. We make comparisons and all kinds of judgements. We employ metaphors.

The idea that slavery was America’s original sin is one such metaphor, used at least as far back as the debate, in 1819, about the admission of Missouri to the union as a slave state. The problem is that it is a weak, misleading metaphor, concealing much more than it reveals about early American history, the institution of slavery, the aftermath of slavery and the messy business of making a nation. We should abandon it. Here are a few of the reasons why.

For starters, the phrase is a theological characterization of a secular institution. For those of us who do not believe in divine law or sins against God, it is an unnecessary confusion of sacred and profane.

As history, it is anachronistic. Today, most devout people believe that chattel slavery was a sin. The rest of us agree that it was a violation of the values we hold closest to our minds and hearts. Yet none of us can deny that in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, human beings were enslaved all over the world, as human beings had been enslaved for thousands of years. Some people, including some of the earliest abolitionists, considered slavery a sin. But many others, including many clergymen, defended it, often on religious grounds, favoring a literal reading of the New Testament that conformed with their values and met their political needs.

Then there is the question of who committed “our” original sin. Was it the European slave traders and enslavers – first Portuguese and Spanish, then Dutch, French and English, all aided and abetted by African enslavers and traders – who began to transport Africans to the Americas in the early 1500s? Were they our Adam and Eve, leaving everyone who came after them as the inheritors of their sin? Or was it the former British colonists, who, in the Declaration of Independence, nearly three centuries later, argued that all men are created equal and condemned King George III for inciting domestic insurrection?

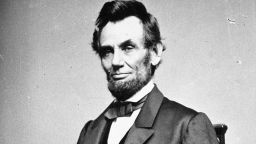

Or was it the men in Philadelphia, 11 years later, who produced a Constitution that preserved and protected slavery in significant ways, including the fugitive slave clause and the three-fifths clause. The former ensured that an enslaved person could not legally escape bondage by fleeing from a slave state to a free one, while the latter designated each enslaved person as three-fifths of a free person for the purpose of taxation and congressional representation. Practically, the three-fifths clause allowed enslavers to maintain political power disproportionate to their numbers.

Symbolically, and horribly, it defined enslaved people (and by extension all African Americans) as subhuman.

If, as so many say, slavery is America’s original sin, the answers to these questions are important, because according to Christian doctrine, those who inherit Adam and Eve’s sin are not responsible for it, and there is nothing they themselves can do about it. They cannot be held accountable. Only God can free them from its grip, as some defenders of slavery in antebellum America were quick to point out.

One was Virginia philosopher and William and Mary president Thomas R. Dew. In “The Proslavery Argument,” published in 1832, Dew conceded that slavery was contrary to the spirt of Christianity, even evil. It was what it was. All the patriarchs enslaved people. God did not object. In the New Testament, Dew wrote, “we find not one single passage at all calculated to disturb the conscience of an honest slave holder.” Slavery was “entailed upon us by no fault of ours.” It was, as the catechism puts it, “a sin contracted and not committed, a state and not an act.” For Dew and likeminded Americans, the contracted sin of slavery was like a disease passed from parent to child. They had to live with it, but it was not something they did, brought upon themselves, or did to others.

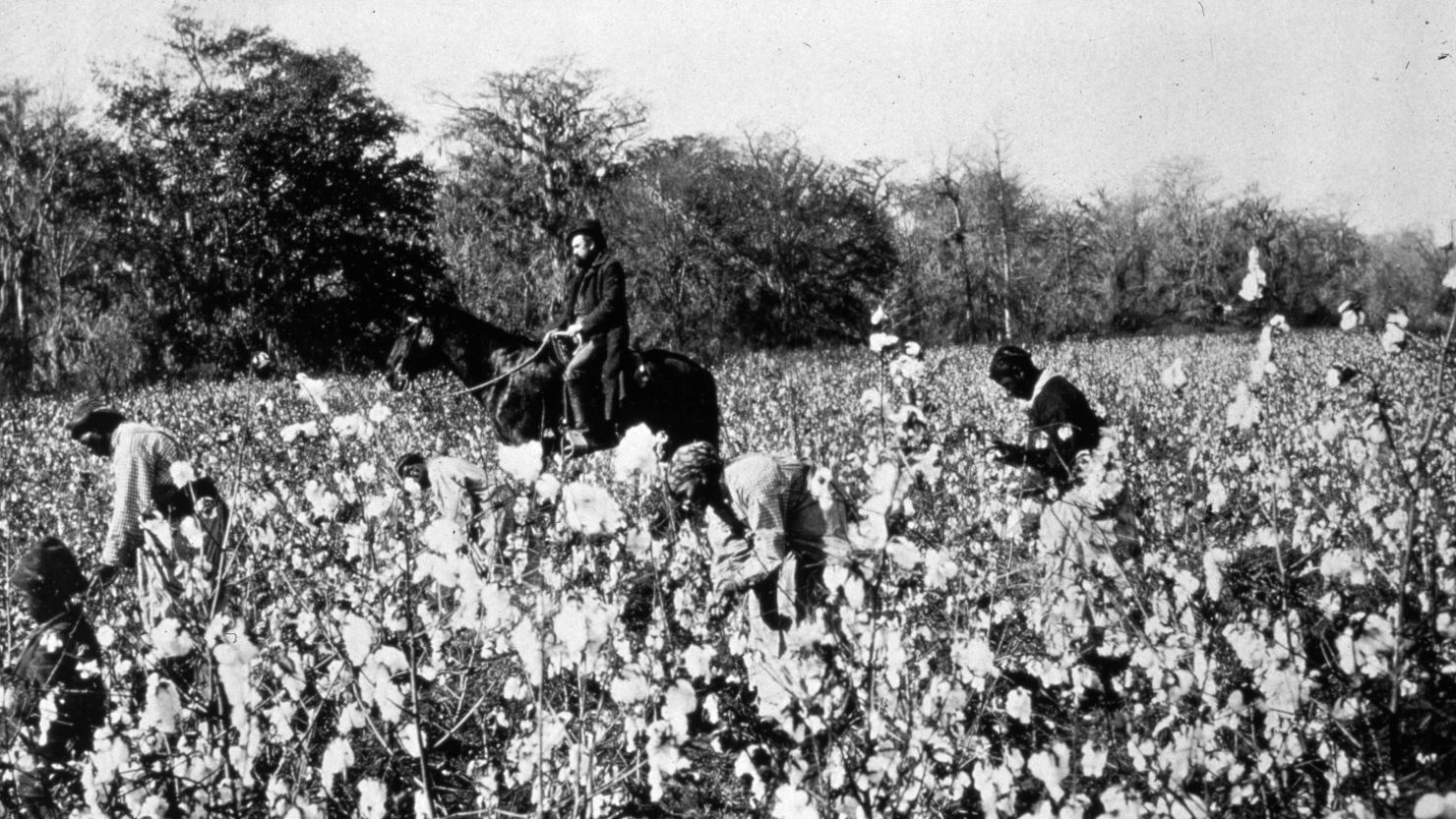

This framing matters, because slavery most certainly was committed, day after day, not just by enslavers and traders but by legislators, lawyers, bankers, investors, and insurers, and all those who benefited from the system and did not struggle to end it. Knowing this – knowing that slavery was an institution made by men and women and sustained by men and women, something that people did to other people – why would we continue to employ a metaphor that suggests that slavery was something we inherited, something we were saddled with, something for which no one was or is responsible?

There’s more. The idea of original sin functions not only to absolve enslavers of responsibility for one kind of atrocity but also to further erase another. European settlers took the land on which enslaved people cultivated tobacco, cotton and rice, from Native Americans. If our British and then American ancestors had a first sin, it surely must include taking that land, which continued for hundreds of years. The making of every great and powerful nation involves a catalog of atrocities. Slavery wasn’t the first, nor the last of America’s. Comparing atrocities for the purpose of ranking them is always a mistake.

Let’s call American slavery what it was: one of the unforgivable crimes against humanity that the people who settled the land that became our nation committed. It was a crime that took myriad strands of Black and White abolitionism, decades of sectional crisis and a great civil war to destroy. It was a crime that contributed, over time, to other crimes and forms of injustice – racism, race prejudice, lynching, exclusion, segregation, discrimination and too many forms of inequality to name.

Many of those crimes and forms of injustice and inequality are still with us, and only we, together, all of us, can do anything about them.