The future of El Salvador’s democracy is under global scrutiny after lawmakers teamed up with populist president Nayib Bukele over the weekend to replace every judge on the Constitutional Court, the highest branch of the country’s judiciary system.

Here’s everything you need to know about what’s happening in the Central American nation, and Washington’s close eye on the situation.

What happened in El Salvador?

Drama unfolded in the halls of power in capital city San Salvador late Saturday, when the country’s Legislative Assembly voted to dismiss the five judges who form the Constitutional Court.

The motion had been proposed by the New Ideas party of El Salvador’s president Nayib Bukele, which has held a strong majority of 56 out of 84 seats since a landslide victory in legislative elections last March.

Lawmakers from New Ideas alleged the constitutional court was impeding the president’s ability to confront the Covid-19 pandemic. Bukele’s critics, however, say he has veered into authoritarian rule.

In March last year the Constitutional Court ruled that it was illegal to incarcerate citizens who had defied lockdown orders, a court rule the president publicly rejected. The institutional clash re-emerged this week as the five judges ruled the vote on their firing unconstitutional. Lawmakers responded by ordering the removal of the country’s attorney general Raul Melara.

Eventually, the legislative branch prevailed: Melara presented his resignation shortly afterwards, and on Monday, five new judges took office in the Constitutional Court.

Questions remain over the legality of the weekend’s events, but the reshuffle has effectively placed put the president firmly in control of all the country’s highest public institutions.

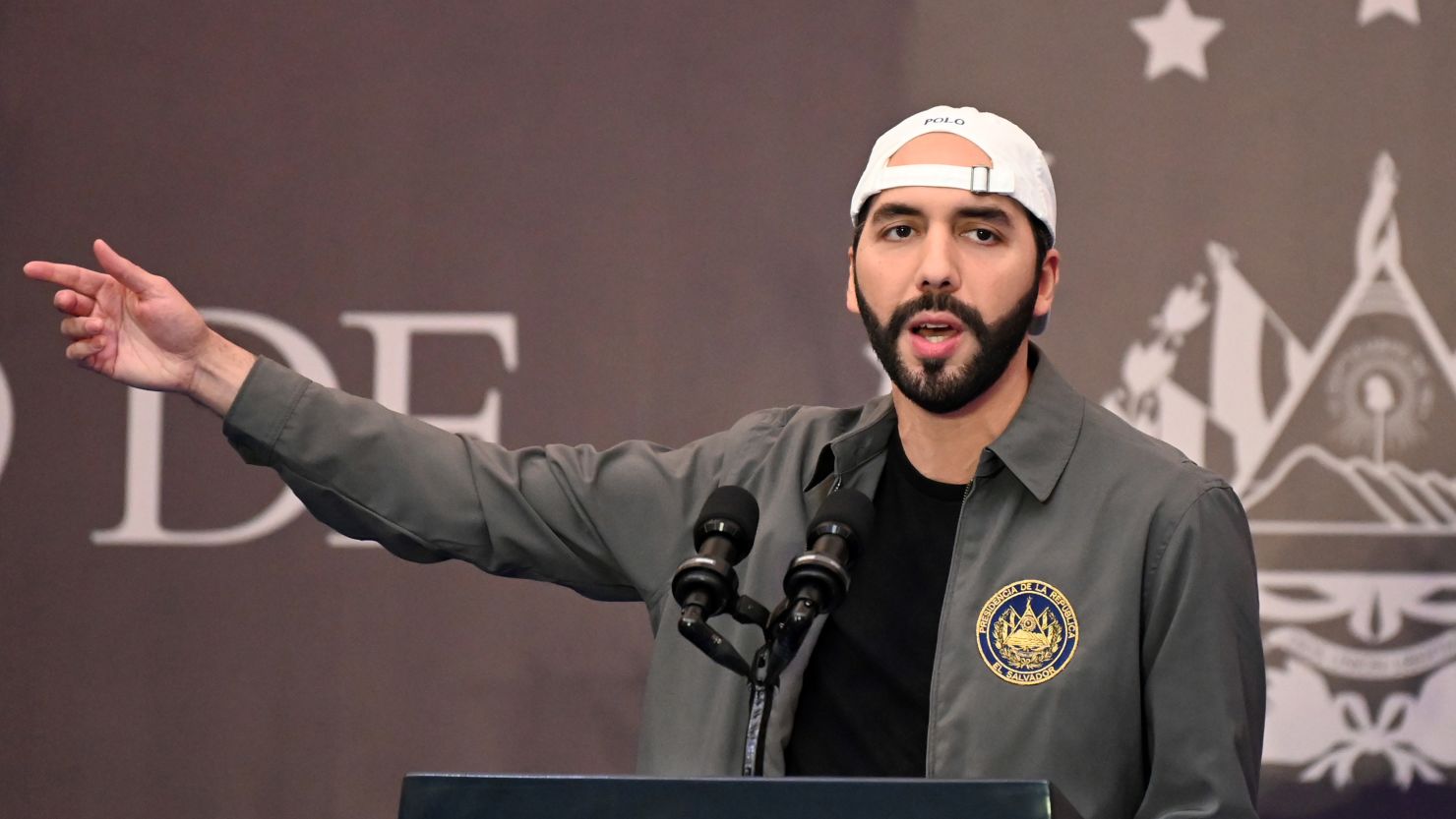

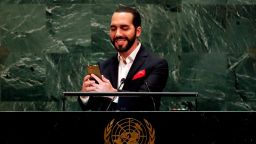

Who is Nayib Bukele?

Shortly after the congressional vote, the 39-year-old Bukele celebrated by tweeting “FIRED” in all caps, followed by five clapping hands emojis. Across the weekend, the President took to Twitter to defend the congressional decision, urging the international community to stay out of the strife. “We are cleaning house,” he wrote.

Bukele, a right-wing populist, rose to power in 2019 on an anti-corruption platform, promising to “drain the swamp” of Salvadorean politics. He is the first president since 1989 not to come from one of the country’s two main political parties, the conservative ARENA party and the leftwing, former guerrilla movement, FMLN.

In his presidential campaign and first year of his presidency, Bukele presented himself as an admirer and close ally of former president Donald Trump, who tweeted praises of the young leader for “working well with us on immigration.”

US relations with Bukele appear to be cooling under President Joe Biden, but El Salvador remains a strategic partner for the US in central America, particularly around immigration, as Washington attempts to stem migration flows into the US with cooperation of Central American governments.

Bukele’s actions have skewed anti-democratic before: In February 2020, he swiftly deployed troops to the then-opposition controlled Legislative Assembly during a clash between the President and congress over an emergency loan. The measure was harshly criticized by the international community, including Trump’s ambassador to El Salvador.

How the world reacted

Several institutions and civil society groups, including El Salvador’s association of private business owners, harshly criticized the judicial dismissals, calling them a “self-coup” and “an attack on democracy and a threat on the freedom of all Salvadoreans.”

Perhaps the highest-profile warnings so far came from Washington. US Vice President Kamala Harris, who has engaged El Salvador as well as the other Northern Triangle countries, Guatemala and Honduras on immigration, tweeted Sunday: “We have deep concerns about El Salvador’s democracy, in light of the National Assembly’s vote to remove constitutional court judges. An independent judiciary is critical to a healthy democracy – and to a strong economy.”

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken also personally called Bukele to emphasize the US commitment to “reinforcing democratic institutions and the separation of powers” in El Salvador.

The European Union’s Representative for Foreign Affairs, Josep Borrell, also shared his concern, saying events in El Salvador had “put in doubt the rule of law.”

Bukele defended his actions, tweeting that he was not elected “to negotiate” with the state’s apparatus but did not publicly respond to the US officials’ criticisms. While the Salvadorean president is accustomed to opposition from within his government and foreign human rights groups, a strong rebuke from Washington ratchets up the pressure.

“Bukele reckons that Washington’s urge to address the migration issue increases his negotiating leverage with the Biden administration, but he may be underestimating El Salvador’s economic dependence on the US,” Tiziano Breda, a Central America analyst at the International Crisis Group (ICG), told CNN.

Millions of dollars in US aid bolster El Salvador’s local economy, curtails immigration and helps fight Salvadorean organized crime, which is dominated by transnational maras such as MS-13.

Breda also points out that the US is by far El Salvador’s most important trading partner and wields significant global influence. Furthermore, she says, Salvadorans living in the US supply more than 20% of their home country’s GDP in remittances.

What comes next?

The situation in El Salvador is the first political crisis in the Western Hemisphere confronting the newly installed US administration. Since the election, Biden’s government has signaled an interest in the region’s most difficult problems, such as Venezuela’s political turmoil, immigration and the environment.

Given Bukele’s ample margins of popularity – 98% of Salvadoreans supported the president’s handling of the pandemic, according to a CID Gallup poll from March this year – the White House may prefer engaging with the young leader on the current crisis rather than unleashing a war of words.

But Washington must also consider the signal it sends to other authoritarian leaders in the region, including Nicaragua’s Daniel Ortega, Venezuela’s Nicolas Maduro and Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro. “Getting away with this would set another dangerous precedent in a region, Central America, that is already affected by similar experiences,” said ICG’s Breda.

“What Bukele may not be considering is what these precedents imply in the medium/long term: more social turmoil, political instability, and international mistrust, if not isolation. Things El Salvador can hardly endure,” he says.