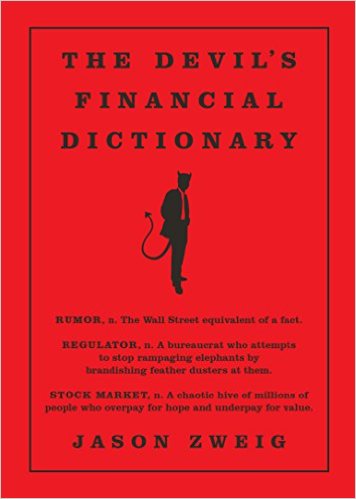

| 0:33 | Intro. [Recording date: May 23, 2016.] Russ: I'm a big fan of Ambrose Bierce. His book is the The Devil's Dictionary, and you have written a--it's really an homage to Bierce, I would say. Is that a good way to describe it? Guest: I was trying to channel him. I make no pretense of being either as cynical or as good a writer as he was. But I certainly was trying to write it in his spirit. Russ: And we're going to get to your book in a minute. Before we do, I do want to let listeners know that Ambrose Bierce was and amazingly entertaining and clever fellow. Nineteenth century, right? Guest: Yeah. Almost an exact contemporary of Mark Twain, I think--he was born in 1842 or 1847, and he is believed to have died in 1914, although, as you know, Russ, nobody is quite sure about that. Russ: Well, I appreciate the assumption that I know. Before we talk about it, I want to quote Bierce a couple of times, give people the flavor of Bierce. He's not, I think, well known; or certainly he's not as well known as he should be. And I encourage listeners to check out his book as well as Jason's. But he defined--his book, The Devil's Dictionary, is a set of definitions of common terms. So, here's his definition of politics:POLITICS, n. A strife of interests masquerading as a contest of principles. The conduct of public affairs for private advantage. I think that's very deep and true. He also defines egotist as--I love this--EGOTIST, n. A person of low taste, more interested in himself than in me. So, what you have done in your book is taken that spirit and turned it toward the financial sector with great success. And we'll get to that eventually, but I first want to interview you and ask you some questions about financial journalism and Wall Street generally; and then we'll turn to the book. You've been a journalist writing about finance for a long time. Guest: Yeah. It's coming up on 30 years now. And in human years, that's really a long time. Russ: Where have you worked? Guest: Well, I did a brief stint at Time Magazine in the mid-1980s. Then I was at Forbes Magazine for about a decade. Then I went back to Time, Inc. in the late 1980s and 1990s, and worked mainly at Money Magazine, and did some things for Fortune and Time as well. And then since 2008 I've been at The Wall Street Journal. Russ: So, what would you say your philosophy of financial journalism is? At one point in a recent article you note that there is a repetitive aspect, when you write about personal finance. What is that aspect, and what's your philosophy of how to deal with that. Guest: Yeah, well, I'll tell a quick anecdote, Russ. Some years ago--many years ago, in fact: it was probably in the late 1990s--I was at a financial journalism conference and a question came from the floor. I was on a panel discussion and the questioner asked each of the panelists: 'Don't tell us what it says on your resume; don't tell us what it says on your business card. What do you do for a living?' And I think the person said, 'In 30 words or less.' And I think there were 4 other people on the panel; and 20 minutes later I finally got a chance to give my answer. So, I did have some time to think about it. Aside from the fact that none of the other panelists had honored the last stricture. But--and what I said was, 'It's my job to repeat myself 50 to 100 times a year so that neither my editors nor my readers will notice I'm doing it.' And there's a reason for that. I mean, I'm in the advice business--much more so than I'm in the news business. Although, obviously, I do both. And there have been any number of times I've been fortunate enough to break news in my columns. And that's very exciting, when I'm able to do it. But, for the most part, I give people advice about what to do with their portfolios. And for people who are saving for retirement or to put their kid through college, the real test is: Can you provide sensible advice that simply improves the probability that people can meet their financial goals? And if that's what you are trying to do, there just are not that many novel, innovative things you can tell people that are good for them. Almost every exciting, new investment idea sooner or later will turn out to be bad for people. So, really, all I'm trying to do is answer the question: Is this tactic, approach, product, strategy, fund, trading technique good or bad for the people who will use it? I'm not trying to answer the question of whether it's good for Wall Street or the financial industry. I'm just trying to ask whether investors themselves can benefit from it. And sometimes the answer is Yes. And that's great. But quite a few times the answer is No. And then people need to hear that. Russ: I just fine it interesting when people say, about a book or a column, 'Oh, there's nothing new there.' Well, it's hard to have anything new, in general. And to have something new that's true is even harder. And most of the things that are old, we've forgotten, or haven't absorbed. So I really like your point about the 50-t0-100 times without people noticing, because most of the simplest lessons on investing--'Don't put all your eggs in one basket' being one of them, just to take an example--is a really good idea. Or, 'If it sounds like a sure thing, it probably isn't,' or as I think you note in your book: It Isn't. And I think that's a deep truth that's just remarkably difficult to remember. And it's good to hear it 50-100 times a year. So I think you provide a very, a valuable service. |

| 7:31 | Russ: I'm curious how you think your profession has changed, if at all, over that 30-year period. Do you feel it's gotten more sophisticated? Less sophisticated? What has changed in your business that you've noticed, if anything? Guest: Well, yeah. Certainly, I mean, the most obvious change, and nobody needs me to tell them this, is that the pace has accelerated. Are investors better-informed today than they were 30 years ago? I don't know. They are certainly more rapidly informed. I think back, Russ, to when my dad, who was a fairly typical investor of that era, in the mid-1970s, I think about what it meant for him to be an investor. He, as I mentioned to you before we started, I grew up on a farm in northern New York State. And my dad, he was, I guess too cheap to spring for the Wall Street Journal. Our local paper, the Albany Times Union, as I remember, had very minimal stock tables. And then, once a week, on Saturday, I think, Barron's would arrive. My dad did subscribe to that for a while. And so, in those days, if you bought or owned a stock, you could easily go almost a week without knowing what the price was. You could call your broker, but for our younger listeners, I have to remind people that there was something called a 'long-distance phone call.' Which was very expensive. Plus, in our area, we were on a party line--which meant that when you picked up the phone, anyone else nearby who was on the phone at the same time as you could hear your conversation. So, these are concepts that people under the age of 30 or 40 are completely unfamiliar with. Russ: Well, some of those people are probably thinking, 'Why don't you just look it up on the Internet?' But they didn't have the Internet in the 1970s, did they? Guest: That did not exist. And you know, in those days it was very cumbersome to know how your investments were performing. And everything was on a multi-day delay. Now, we could ask the question, very interesting question, I think: Did that make investors worse off? Or might it have made them better off? And certainly my dad never traded--you know, eventually he would decide it was the time to sell a stock, but he never would do that on any horizon less than, I don't know, a year or two or three. And he never did it in response to news. It was always in response to what he perceived as the fundamental health of the underlying business. Russ: That's a remarkable thing, that change in speed and information. But the other thing that I think of, when I think over that time span, the two things that strike me that have changed are the, what I think of as the democratization of finance: The ability of everyday people to invest money and the availability of instruments like Index Funds, which, I think--those would be the two things I would pick. Do you think those are important? Am I exaggerating? Guest: Yes. Absolutely. I think we will look back with the judgment of history and the luxury of hindsight, decades from now; and I think we will come to regard the invention of the Index Fund as one of the greatest innovations in financial history. You know, one point I often like to make is: Investors hear a lot about the concept of total return--which is not just the increase or decrease in the value of your investment from the change in its price, but also gives effect for the value of the dividends or the interest income that you might reinvest back into the asset. Russ: Along with taxes and commission, which are two things investors often forget. Guest: Yes. Exactly. Correct. But if you think about the often-cited numbers that the U.S. stock market has returned, more or less 9% a year on average since 1926, or some people even take it back centuries or earlier, that number assumes that you had taken the dividends that stocks generated and reinvested them. And what no one ever points out is, until 1975 or 1976, when the Vanguard Funds introduced the S&P500 Index Fund, that went on to become, many years later, one of the largest Mutual Funds in the world, until that time, no one, individual or institution alike, was earning that total return. It was completely hypothetical. Because the ability to take those dividends and then reinvest them across 500 stocks in perfect proportion was completely impractical. Not to mention incredibly expensive. And today you can do it for almost nothing. Russ: Yeah. The transactions costs of entering the stock market with small amounts was just out of the question. It's a great point. That has changed a lot. Some people would say, you know, as you said--there are a lot of changes; people debate about whether they are for the better or for the worse. But I think that one's probably for the better-- Guest: I would agree. I think the democratization and the instantaneous nature of information is very unhealthy. I think it's really bad for investors to have the ability to get, sort of, momentary updates on every single asset they own. That's not a good thing. Certainly, if any of us knew, at, you know, 1:43 in the afternoon that the value of our home had just changed from what it was worth at 1:42 in the afternoon, we would start to get crazy about whether we should still live in our house, or should we sell it, should we buy a new one? What's wrong with my neighborhood? If you think about it in that perspective, the idea that being constantly updated on your portfolio holdings, it's just a terrible idea. However, the ability to participate in the financial markets at virtually zero cost is an incredibly powerful boost to capitalism and certainly if you look back in the 19th century or earlier, the proportion of the public investing in the stock or bond markets compared with today--people have a much greater stake in the American and the global economy than they ever used to before. And that just can't possibly be a bad thing. Russ: And if they followed your advice, of course, they'll be much more successful. Because one of the challenges of that democratization is the incentive to follow those minute-by-minute, second-by-second news blasts, news bursts, with changes in your portfolio. Which is really a bad mistake, as one of my favorite definitions in your book is the definition of "Day Trader"--in your definition, is one word: "Idiot." And there is a challenge--and if you look up "Idiot" in the book, it says "Day Trader." It's a beautiful symmetry there. But there is this temptation to, moment by moment, adjust your portfolio. I certainly--I look at mine about twice a year, and I sleep well at night. I encourage choosing a philosophy that lets you do that, even if it's not the best philosophy, because you will be a happier person. |

| 16:22 | Russ: I want to turn to your work with Daniel Kahneman. It says in the book Thinking, Fast and Slow, Kahneman's work: "My thanks go first to Jason Zweig, who urged me into the project and patiently tried to work with me until it became clear to both of us that I am impossible to work with." That's very nice. Sort of. So, what happened there? What was your role in the project, and what happened? Guest: I think Danny was being his usual self-deprecating self there, and maybe having a little fun at his own expense. Yeah. I spent pretty much all of 2007 and 2008 working with him on the book, helping him research it, write it, edit it. It was, I would say those were two of the greatest learning years I've ever spent. It was an amazing opportunity to learn at the feet of, you know, one of the greatest observers of the human mind I think the modern world has seen. And we had a lot of fun. It was a ton of work. And Danny sets very, very high standards, especially for himself, which is what he's really talking about there. And eventually we both decided that maybe getting a full-time job might be a little more reassuring to me. So, when The Wall Street Journal got in touch with me, that's when I sort of moved on from the book project. But it was a terrific experience. And we definitely have remained friends. Which is terrific. Russ: Is that a--I mean, that's an unusual attitude for someone who was part of a project that didn't work out: it was a successful project, obviously. Regret? Or are you making lemonade out of the lemons? I mean, I love that you thought it was a great two years, even though it didn't pan out exactly. Guest: Well, you know, one of the most fascinating things I learned about working with Danny was that he really meant it when he said--because he and I have known each other for a long time, 20 years, I think, at this point. And many times over the earlier years he had sort of warned me that people who study psychology and the pitfalls of the human mind are no less prone to making errors of judgment and cognition than people who don't know anything about it. Russ: It's alarming. Guest: And I remember very clearly the first day we started working on the project. Danny said, 'Above all else, I do not want to commit the planning fallacy.' And, I'm sure you are familiar with it, Russ; for some people in our audience, I'll just briefly summarize it. The planning fallacy is the shortcoming in human judgment that so many of us fall into: when we are facing a big project, we estimate how long it will take and how hard it will be to do based on our own experience, and also how we feel about the project, rather than doing what we should do, which is consult a ready-made database that's already available to us. Which is, ask the question: Of all the people who have faced a similar commitment, how long did it take them? And what was their experience? And then you would take the average of that; and that would be your baseline expectation. And so think about when you renovated your kitchen, for example. Russ: Yeah. Guest: Your contractor renovates kitchens all the time. Your contractor looked at your kitchen and said, 'I think it will cost--', well, you know the number. You might not want to say it. I'm guessing it was some $35,000. Russ: Let's call it x-thousand; x could be 35. Guest: Right. And it will take y months to finish. And of course when it was done, it cost you, I'm guessing, 2x. And it probably took 2y units of time to complete. And so, Danny of course is very aware of all of this. He's the person who first documented the planning fallacy. And he said, 'Let's make sure we don't commit the planning fallacy.' So we went through this scenario, planning exercise that involved making a realistic estimate of how many words will be in the final book, how many words a day can we realistically produce based on what other people committing to similar projects had done? And also, what's the probability that we might never finish? And so this was a really detailed exercise. It took us quite some time. And when we were finished, I think we concluded that it was doable in 3 years at the worst. And so that would have been April of 2007, I think. And I believe the book came out 5 years later? But that was after several times when Danny almost quit entirely. So, I mean it's--he and I together committed the very fallacy that we were trying so hard to avoid. And to his credit he said we still may be committing it when we were done with the conversation. And he was right. Russ: I think in his book on writing, Stephen King talks about his strategy for writing the book, which--or just, I think living--which is that he would get up every day and write x thousand words. And, x, I think is--I can't remember but it's a frighteningly large number for him. It's at least 10. Which is 40 pages. But I can't remember exactly what the number is. But it's the kind of number that for most of us you might have done once or twice in your life. And it's one of the most exhilarating days of your life: you realize you are on an incredible roll. But he would do it every day. And when we put the Highlights up I'll put in brackets what the actual number is; I'll look it up in the meanwhile. And he would do that, and he would be done usually by noon. And after that, after he had hit his mark, he would then spend the rest of the day shopping or relaxing, whatever he did. And he did that every day. And so he actually could plan how long it would take him to write one of his "normal" books. Then, when he wrote a book that was a little bit different, outside of the ordinary, maybe it was a little bit harder to plan. And as he got older I think it took him till like 2 o'clock, or 1 o'clock till he hit his mark. But he's unusual. Most of us suffer from being unable to predict with any accuracy how long projects are going to take. Guest: Yeah. I would say he's extraordinarily unusual. Russ: Yeah, he is. Way out on the right-hand tail, maybe by himself. Guest: Yes. |

| 24:40 | Russ: Now, a more serious question about that book and about behavioral economics generally, which is a theme that runs through your book, the Devil's Financial Dictionary. You make fun of economists; I do, too; it's okay. But you are prone to point out in the book many of the pitfalls that investors have due to their biases and the challenges they face in assessing the world accurately. Some of those findings have come into question because I think some of the experimental work, there have been struggles to replicate it accurately, or to replicate it at all. Have you followed that literature? Have you thought about those issues? Guest: Yes. I'm quite familiar with the controversy in social psychology, particularly a bunch of them, the priming experiments, which people are given subtle, unconscious reminders of various environmental factors or other decision variables. And a lot of those experiments are not replicating or are only partly replicating. And now, of course, predictably there's a pushback against the-- Russ: the replications-- Guest: yep, against the failure to replicate. And the controversy hasn't really settled out. But I think where I come out on this, Russ, is that while a lot of the experiments in social psychology that involve those unconscious variables that are usually tested with priming experiments, the bulk of the research in behavioral economics and cognitive psychology, I don't think is quite that fragile. Things like the anchoring experiments that Danny Kahneman did in the 1970s with his research partner Amos Tversky, where simply putting people in mind of any number, no matter how irrelevant, tends to shape their judgment of the number they are being asked to measure--I don't think those results go away when you try to replicate them. I think they are strong. And I think a lot of the basic findings in behavioral economics, for example that people are overconfident about their judgments or their evidence--I think a lot of those results hold up because I think they are getting at basic aspects of human nature, what it means to be human. Russ: Yeah, I agree with that. Guest: Yeah. I don't think those things depend on who is running the lab or whether somebody unfairly manipulated the software. It's the software we're born with that's really determining the results, not the software that's measuring the experiment. Russ: Yeah, I have to agree with most of that. I think the only question is the point that Vernon Smith made on this program a few years back, and we'll put a link up to that episode, where he talks about the power of markets and market information to constrain those kind of mistakes that we have a tendency to make. And I say that as someone who is--I think I have tickets to Hamilton. I say, 'I think,' because Ticketmaster isn't shown on my page. There's some uncertainty about this. But assuming that I have those tickets, I paid about $180 for them to take my family to New York and see the show. The market price of those tickets is about $1000, per ticket. And so I'm having a conversation with my family--just because it's interesting and they are interested in it--about the fact that it's going to cost us about $1000 apiece to go, but had the tickets been $1000, we wouldn't have purchased them. We would have waited till they came down. And I think the challenge is not to say, 'Well, that's irrational.' The challenge is to say--and we're going to go, I'm pretty sure, assuming Ticketmaster comes through and we find my tickets. We're not going to sell them on the street. And that includes my middle son, who raised the question--he's the biggest fan of the show--he raised the question whether he would be allowed to sell his ticket personally and pocket the difference. And we said, 'No.' But I think the challenge is, rather than just saying, 'Well, that's irrational,' to go when it costs you a thousand but you wouldn't go if you had to pay a thousand out of pocket--the challenge is: What is going on there? And I think that's where the most interesting aspects of these puzzles come in, is the fact that we as a family have been talking about it--we bought them back in September which is why they were only $180--is it the anticipation that makes it hard to sell them and give up that expected treat? Or is it something else? Is it just something hardwired that I've got to deal with? So I think that's where the future of this kind of work has been going. Guest: Yeah. I completely agree. And by the way, you'll love the show. Not that you need me to tell you that. Russ: Is it good? Guest: It's phenomenal. Russ: That's what they say. Guest: It's beyond description, it's so great. But I--if there were one word I could banish from the vocabulary of behavioral economics, it would be 'irrational.' I can't tell you how much I hate that term. And I think there's two reasons I hate it. One is, so often it is used as sort of a secret password, like a shibboleth, to use the ancient Hebrew term: sort of, you know the secret handshake, so you are rational; but all those other people, they are not on the inside; they are just irrational. There is a real sort of divide between the so-called 'smart money' and everybody else, and the idea is, 'We're rational, but they're all crazy.' And in fact most of the people calling other investors 'irrational' are committing the same imperfections of human reasoning that the people they criticize are. The second reason I don't like it is because I'm not sure the term has much meaning. Investors aren't rational or irrational. They are just human. And I think it's human when something you paid $180 for becomes worth $1000 to start asking yourself a different set of questions. I mean, maybe we should pocket the difference? It's a lot of money. Russ: And there are times I would have in my life. Guest: Yes. Russ: And gladly. Guest: There's a lot we could do with the $820 pre-tax profit that we might not be able to do otherwise. And that's true even in an upper middle class household like yours. And, you know, the consumption value of a night at one of the greatest musicals in modern America is huge. But $1000 dollars-- Russ: $820 dollars-- Guest: is also, if you spend it wisely, you can--there's a lot of optionality in that. You could certainly spend it on something else that might give you at least as much pleasure. And also you are playing with the house money, which changes the dynamic as well, because that $820, that's yours to play with. Russ: Yeah; I don't like to remind my wife or kids of this, but the show is going to be around for a very long time. I have a feeling you'll be able to see it in 10 years. Although, seeing it in a year or two it's still going to be very expensive, in 10 years it will probably be cheap. It'll be revived after it goes away. But the question is--this is the part I don't like to remind my wife and kids about--is: They might need to revive me to see it. So one of the reasons I want to see it now at that expensive opportunity cost is that I might not be here to see it another time. And of course you could say, 'Well, then it won't bother you: you won't be here.' But anyway. Let's leave that philosophical question behind. |

| 33:55 | Russ: I want to turn to--let's turn to the book. Which is a lovely and charming book. But one could argue it's a little too cynical. Bierce could be painted as a cynic; and you, writing in his spirit, could be doing the same thing. A theme that runs through your definitions in this dictionary--and just for listeners, it's a glossary. That's what The Devil's Dictionary was, by Ambrose Bierce, and The Devil's Financial Dictionary, by you--a glossary of terms, humorous, but pointed, witty, and sometimes a bit cynical in their tone, definitions. So, one of the things that runs through your definitions is we are often exploited by Wall Street as individual investors. Do you really feel that way as strongly as it comes through in the book, or are you just being a little Biercean there? Guest: Well, yes. I do. I think it's fairly easy for people to avoid being exploited. But you must be an intelligent consumer of information and you have to control the relationship that you have with Wall Street and the financial industry. But there's--I don't think there's any question that the people on the other side of the trade from you are trying to take advantage of you if you let them. Because that's the main reason they want to trade with you in the first place. They believe that if you're selling, they'll make more money buying; or if you're buying, they'll make more money selling. And often they know more than you do. And often when you think you know more than they do, you are wrong. All things worth bearing in mind. Russ: No, those are all good. But I would say that most of the cynicism in the book comes from the people who are facilitating that trade or who are suggesting that you make that trade or are advising you about how to think about making that trade. The people who provide financial information--the brokers, the dealers, the banks, etc.--the commissions they charge, the advice they give, and the products that they market. So, you want to defend or criticize them as well? What do you feel about that? Guest: Well, look. I mean, the entire industry of financial intermediation is really based on this idea that people cannot help themselves, they cannot get their fair share of what the financial markets will return, without someone helping them and charging hefty fees in return. And of course what we are seeing throughout the economy, Russ, you know, in companies like Uber or Airbnb or any number of other examples we could name, is this sort of blunt sort of almost destructive disintermediation where people are going directly to the source of the service or the good and eliminating or at least reducing the take of the middleman. And as we discussed earlier with an investment like an index fund or an ETF (Exchange Traded Fund) which is just a variant of it, you know in many cases you can buy the entire stock market or the entire bond market, pay no commission of any kind, and pay an annual management fee of just a fraction of a percentage point per year. And the idea that you need to pay somebody 3-5% up front and then 1-2% annually in perpetuity just for putting you into something like that in the first place--I don't think that's a sustainable idea in 2016. I think that that's a way of life that will continue to shrink. Russ: Yeah. I agree. You define 'irrational' asIRRATIONAL, adj. A word you use to describe any investor other than yourself. And I remember a friend of mine who is a lawyer who said, while he was a good investor, of course, and well informed, his secretary couldn't be expected to invest her own money. And that was his way of making a case for Social Security--that if we had private retirement accounts, people would make all kinds of mistakes. Of course, I would probably look at his investment decisions with disdain. I think there are increasingly vehicles to make good investment decisions easier, if you are, as you say, wise enough to control your impulses for a larger return. Guest: Yeah. And I'm a huge believer that the single greatest asset any investor can have is self-control. It took me probably about 30 years of writing about financial markets to realize that if you had to distill investing success down into one single principle, that would be it. As Benjamin Graham wrote in The Intelligent Investor, the investor's biggest obstacle is likely to be himself. Actually, he said: The investor's biggest obstacle and worst enemy is likely to be himself. And it's so true. Because you can have well-informed principles; you can do thorough research; you can have access to the best quality information; and then, you know, you get some tip at your country club that, you know, Tesla shares are cheap and you run out and put all you money in Tesla right before it tumbles. And you let go of your self-control for that one moment; and that moment of weakness is what takes you from outperformance to underperformance. And self-control is what has made Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger, and certainly what made Benjamin Graham into great investors. But most investors spend all their time and energy sort of pursuing other objectives. Like, getting the fastest information first, or finding the best software, or using some new analytical method that nobody else had thought of. And none of those things will get you where you need to go if you do not have self-control. Russ: Yeah, I don't know if I've told this story before on the air but I'm not sure I have: George Stigler, Nobel Laureate at the U. of Chicago, reportedly told the story of a lunch where he and some other faculty members were sitting around and they realized that there was an arbitrage opportunity--I think it was wheat--between the United States and England. And they executed a trade, not realizing that the definition of a ton in England is not the same as the definition of a ton in the United States. And Stigler, after mentioning that, would say, 'That was one of the most expensive lunches I ever had.' And here's a man who is, I would say in many ways, whose life was devoted, as was his good friend, Milton Friedman's, to understanding there's no free lunch. A person who would happily tell the story of the $20 bill on the ground and the person going to pick it up and being told, 'Don't bother picking it up because if it were really there, someone would have picked it up already.' And yet, at this lunch, this group of extremely bright people convinced themselves that they were going to be fabulously wealthy. Guest: That's an amazing story. Russ: Yeah. It's depressing. But it's good to remember. Because we all have those moments. And it's very useful to find heuristics for remembering heuristics, I think. Unappreciated area. |

| 43:12 | Russ: I want to read a definition--I'll try to read a few of them. This is the definition of Bright Line in your book:BRIGHT LINE adj. and n. A line dividing ethical from unethical behavior that is often blurred until dull. The simplest "bright-line rule" or "bright-line test" answers the question: Would my mother be proud of me if she knew I was doing this? On Wall Street, the voice of Mom may be the least audible to those who most urgently need to listen to her. The financial industry would harbor much less darkness if every action had to pass Mom's bright-line test. I really like that. It reminded me a little bit of Adam Smith's impartial spectator and how Smith notes that in the heat of the moment, the spectator is very hard to hear--when you are doing something unethical that you really want to do. I want to take it in a more serious direction. Do you think Wall Street got off too easily in this last crisis in its failure to act ethically, and did too many things that Mom would be ashamed of? Guest: It's really hard to say. I think the thing where I've started to come out on it is that what society--and I guess I'm thinking of American society in particular because I'm just less familiar with Europe and Asia--what society really missed out on in this financial crisis that I think we had as a nation after the Crash of 1929 was, we didn't have any public hangings. And I'm using the term metaphorically, obviously. Nobody was hanged for financial crimes at least after the Crash of 1929. But there was an enormous amount of ritual humiliation for the leaders of the financial industry, who effectively drove the nation into the Crash of 1929 and to some extent into the Great Depression. And some people did do prison time. For example, Richard Whitney, who had been President of the New York Stock Exchange. But the senior executives of the largest banks in the country--and in those days most of them were commercial banks, like Chase--the ancestors of Chase Manhattan and Citibank. You know, they testified before Congress at the Pecora Commission, and Ferdinand Pecora was certainly one of the toughest prosecutors in U.S. history, and just a ferocious interrogator. And most of these people were absolutely humiliated. And a lot of the practices that were exposed really were damaging to the public confidence and arguably to the integrity of markets. And the financial legislation that was passed primarily beginning in 1933 was really a response to all of that testimony. And after the Financial Crisis of 2008-2009, we got, you know, the Dodd-Frank Act, which is thousands of pages of sort of microscopic regulation of everything under the sun, and commissioning of all kinds of studies and the like. And we got some testimony before Congress and the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission. But we didn't really get the level of public apology and humiliation that the financial industry had to go through in the late 1920s and early 1930s. And I think that's unfortunate. The public would have benefited from it; and the industry would have benefited from it. And that kind of catharsis is something we did not go through and I think probably should have. Russ: Yeah. I think it's shocking how little we learned from it. You can debate about what we should have learned--and people don't agree on it, politically, ideologically: people on the Left and the Right draw different lessons. But what I've noticed is that no matter which lesson you draw, we are still doing it. It doesn't matter if you are on the Left or the Right, if you think it was a government problem or a private problem: None of the obvious lessons led to, right or wrong, led to changes that they should have. And I agree with you--I think it's a, I actually think it's a tragedy. |

| 48:07 | Russ: Let me turn to your definition of central bank, which I really enjoyed.CENTRAL BANK n. A group of economists who believe that their current forecasts will turn out to be accurate even though their past forecasts have been unreliable, that their present policies will succeed even though their past policies have failed, that they can prevent inflation from occurring next time even though they didn't prevent it last time, they can foster lower unemployment in the future even though their practices worsened it in the past, and so forth. We should now be able to answer this riddle: What's the difference between a Central Banker and a weather vane? They both turn in the wind, but only the Central Banker thinks he or she determine which way the wind blows. Are you really that cynical? And, do we pay too much attention to the pronouncements of Central Bankers? Guest: Well, so that's two questions. The answer to the first is, yes, I really am that cynical. And the answer to the second question is I think indeed there is a lot of intellectual honesty within central banks, but it doesn't always get reflected in the formation of policy. You know, if you ask anyone who works at the Fed, 'How accurate have your past forecasts been?' most people will say, 'You know, somewhere around the flip of a coin, maybe a little better,' with an emphasis, I think, on maybe a little better. But, I think they are aware of the limitations of their ability to predict the future. And certainly the history of Fed policy shows not only does the Fed not know what the economy will really do in advance, but the Fed doesn't even know what the Fed will do in advance. So often, the Open Market Committee will make a periodic statement at its regular meeting, saying, 'For the foreseeable future, we believe that policy should remain accommodative,' which basically means 'we are going to be easing, using an easy monetary policy.' And then three weeks later, they raise interest rates because new data become available. And that's really the historical pattern you see. So, I mean, I think, you know, if there's one overriding theme to the book, one of the things I tried to get across in The Devil's Financial Dictionary is the importance of just being humble before the financial markets. I mean, people are humble before nature. Think about when you stand on the brim of the Grand Canyon or you walk to the edge of the ocean or you look up at the stars. People feel this sense of awe and wonder and smallness, because we are small when we compare ourselves with the natural world. Well, individuals, and for that matter policy makers are small when we compare ourselves with the financial markets. But most of us forget that. And we think, 'Oh, well we have better data,' or 'We know something the other guy doesn't.' And in fact we should have that same sense of just being a speck of sand on a long beach, and just remember that whatever we know is very small compared to the totality of the information that's out there. And central bankers, I think, could do a little better job of keeping that kind of humility in mind. Russ: Well, my listeners know how much I like humility. One of my pet peeves is the encouragement of the teaching of personal finance to high school students and children, which is, in the abstract, a fine idea, but is often bizarrely, in practice, by giving kids a fixed amount of money and having a contest to see who can make the most money over 3 months--you know, stock market contest, investing contest. Which has to be probably the worst single lesson I think you could teach anybody, I think, about investing, which is, you encourage people to have a short-term horizon; encourage people to strategize by taking as much risk as possible because that's the way you win--it's your best shot in a large contest; losers get zero in this game. It's a winner-take-all--which is nothing like the actual stock market. So it's a horrific set of lessons. And it strikes me that we would be much better off teaching humility and self-control. Which, of course, are hard to teach. That's another problem. It's a lot easier to run a stock market contest, I guess. But, other than reading your column 50 to 100 times a year, what might we do to encourage our own humility and our own self-control, given those problems? Guest: Well, first of all, Russ, I could not agree with you more. A couple of years ago I wrote a column about exactly that, the stock market game. And, I think it's shocking, because so many educated Americans advocate financial education in the schools. And I think so few realize that the form it often takes is essentially teaching impressionable young people to gamble in the financial markets. Not to invest. Not even to speculate, but to gamble. And the other thing is, which is almost never mentioned, is: the stock market game allows the kids to use leverage. They are actually borrowing money or trading on margin. And I cannot imagine a worse way to teach young people how to be responsible with their money than urging them to gamble. I think instead of that we should be emphasizing basic shopkeepers' math: If all you can do is apply simple arithmetic to an investment portfolio, or to the other decisions in personal finance about banking and borrowing, then you would be pretty well served if you just remembered reading, writing, arithmetic, or you remembered addition, subtraction, division, and multiplication, and really simple principles of accounting. That would be much better than teaching kids to gamble and pretending that you are giving them some sort of financial training. As to self-control, I think that has to come from the family and from peers and I think it's very difficult for young people in a world where everyone carries a supercomputer in a back pocket and communication is instantaneous. And gratification feels instantaneous. Very hard to get people to defer a reward into the future and realize that that can be a good thing instead of a bad one. I have teenagers; and I was a teenager; and I think we can all sympathize with that problem. Russ: Yeah. That's a problem that human beings are going to struggle with, well, forever; but I think as you point out in particular today, it's especially hard. So, I have a new challenge for you, Jason. I think, having channeled your inner Ambrose Bierce, I want you to challenge your inner Rudyard Kipling, as you just gave a bunch of sentences that started with the phrase, 'If you can.' I think of the Kipling poem "If" which is about the virtues--it's written, as it was, a long time ago, from a male perspective, but it's a pretty universal set of advice. And he doesn't have a lot of financial in there--he does a little bit, I think. But [?] should write an investment version of that and maybe teach it in schools and get kids of memorize it. |

| 59:51 | Russ: We're almost out of time. I want to close with, asking you to tell a story which you told in a column you wrote about 3 years ago. You had written your 250th column for the Wall Street Journal's "Intelligent Investor" column, and you had won the Gerald Loeb Prize for financial journalism, and in the wake of that you wrote a column that was somewhat of a summary. We'll put a link up to it. It's a very nice piece. But in there you tell the story of visiting your father, and I'd like you to close with that. Guest: Yes. So, my dad was a remarkable man, Russ. He had grown up on a farm in northern New York state. He was a soldier in WWII. Political science professor; and later in life an ardent antique dealer. But he was an incredibly literate man. And my senior year of college, he was terminally ill. And I was going to college down in New York City, and most weekends I would take the train up to Fort Edward in Upstate New York, which then was the closest train station. And my dad was very sick. So, this one particular weekend, he asked me, as he always did when I got there, 'What have you been reading?' And I kind of fluffed up my 22-year-old feathers and said, 'Kierkegaard.' And my dad said, 'Well, what is he telling you?' And so I had just read this passage on the train that I instantly memorized then and I still remember, where Kierkegaard had written on: No man--I think maybe it was no individual--No individual can assist or save the age. He can only express that it is lost. And, you know, as a callow 22-year old, I thought that was so beautiful. And my dad said, 'Well, he's right. But that's why you have to try to assist or save the age.' And it was a remarkable moment that still kind of gives me chills when I think about it, because my dad had studied a lot of philosophy and he knew Kierkegaard very well. And what he was saying was: It doesn't matter whether saying or doing the right thing will make a difference; you have to try it anyway, because that's the only way that you as an individual can attain any dignity in this world. And, you know, in the advice business, which is what I do, when I was very young I used to like to think, you know, I can get so many investors to improve their behavior and make a huge difference in their lives. And as I've grown older I've really come to appreciate the importance of what my dad said, which is that it's not about trying to get everyone to do the right thing. It's just about trying to get anyone to do the right thing. And even if no one listens, you at least know that you did your best as you saw it to try to make the world a little bit of a better place. Whether anybody listens or not, maybe you never really know. But the effort is sort of all we have. And that's what makes it worthwhile. |

Jason Zweig of the Wall Street Journal and author of The Devil's Financial Dictionary talks with EconTalk host Russ Roberts about finance, financial journalism and Zweig's new book. Zweig discusses rationality and the investor's challenge of self-restraint, the repetitive nature of financial journalism, and the financial crisis of 2008.

Jason Zweig of the Wall Street Journal and author of The Devil's Financial Dictionary talks with EconTalk host Russ Roberts about finance, financial journalism and Zweig's new book. Zweig discusses rationality and the investor's challenge of self-restraint, the repetitive nature of financial journalism, and the financial crisis of 2008.

READER COMMENTS

Mark

Jun 6 2016 at 1:10pm

Jason Zweig gives great insight on financial markets.

Russ sometimes doesn’t seem to trust markets especially as it applies to the 2008 financial crisis. Lower prices for financial instruments were bad for some and good for others, why do so many economists feel we should do “something” to save those who are hurt by lower prices? This argument of cascading failures has no evidence in financial history, when has this ever happened where a free market financial system was destroyed? What happens is bad debts are extinguished and assets pass to more prudent hands. Unfortunately this did not happen and we are still in precarious shape with incentives misaligned by government.

FallLine

Jun 6 2016 at 3:44pm

Zweig’s critique of the accuracy and humility of central bankers is good, but perhaps misrepresents the goals of central banks (or at least the Fed).

The Fed is not particularly concerned about disseminating accurate forecasts of the economy. The Fed takes actions (as we all know) toward the purposes of hitting a particular inflation target and minimizing unemployment rates.

Without getting into whether or not the actions the Fed takes toward those goals actually have the intended effects, it seems evident that the Fed’s public statements regarding their intentions are themselves meant to work toward the Fed’s goal by manipulating people’s behavior by setting expectations for future Fed behavior, regardless of what actually happens or what the Fed actually does.

It’s entirely possible they, the humble central bankers, know perfectly well their forecasts do not reflect reality, but do not care as long as the expectation of those forecasts incentivize desirable behavior

Whether or not this kind of manipulation actually works, and whether or not it is harmful to the credibility of the Fed is another question entirely, but any discussion of the accuracy of central bank forecasts should factor in the question “What effect does the Fed hope to have by making this statement?”

Jerm

Jun 6 2016 at 3:49pm

Two bits:

First, my memories of using “the stock market game” as a high school teacher was exactly what was described in this episode. To go even further, the stock market game was pre-packaged by one of the large financial products companies, with literature and in-person demonstrations that heavily suggest full-fee mutual funds as the best route for everyone. The student teams that are “winning” the game get listed in the Sunday newspaper. Everyone pats themselves on the back for helping the children. It was empty calories, and I’m not sure if it was better or worse than teaching financial literacy by “showing the students how to apply for a home loan.”

Second, the obsession with “rationality” is something that I questioned back in grad school. Rationality should be simple: expecting the same results from the same action. We know which pedal is the gas and which is the brake. And it would be irrational to think that the pedals somehow change spots while we are on the freeway. But that simple concept gets combined with “utility maximization” (which is just a mathematical convenience, since it is the optimization of a single variable), leading economics for many years to suggest that there is an objectively “right” way (and everything else is irrational). And that’s just not workable anymore.

Good episode. And go to see Hamilton. You can overcome the regret of not having $1000 by picking up a few extra shifts at work. You cannot overcome the regret of missing out on what is obviously a complete work of art, performed by the original cast (if you go in the next month).

Carter Ferrell

Jun 7 2016 at 10:25am

I still haven’t finished this episode, but I simply had to stop for one moment to express my desperately heartfelt appreciation of Zweig’s criticism of the craze surrounding “irrational” behavior analysis. It feels like a breath of fresh air to hear that on one of my favorite podcasts.

It’s not that I believe that people are completely rational beings; clearly there are some instinctual failings that cause people to act stupidly for stupidity’s sake, but frankly my experience with the vast majority – nearing totality – of examples supporting irrational behavior analysis exhibit obvious failings, such as hindsight analysis and correction, or substitution of personal knowledge and values in place of the subject being documented, such as the example that Zweig presents of savvy traders that know their way around are “rational”, and all of the amateurs are just “irrational”.

I read example after example of irrational behavior that more often than not presents cases in sterile A vs. B scenarios. Frequently in life we proceed blindly without the full knowledge of facts and circumstances, but nevertheless fate forces us to make decisions that may in hindsight be determined as wrongful conclusions or actions, but that is not to say that a person was acting irrationally; and so I have to applaud Zweig’s preference to say that at the end of the day, “[people] aren’t rational or irrational, they’re just human.”

[Spelling of Zweig’s name corrected. –Econlib Ed.]

Shayne Cook

Jun 8 2016 at 10:47am

Thank you both for the discussion here.

I think Jason Zweig may be able to help with a memory lapse I’m having regarding an investor story I read (a couple of decades ago – mid/late 80s or early 90s). I recall some important features of the story (I seem to recall it appearing in the hard-copy of the WSJ at the time), and even “clipped” it to save and refer to – but I’ve lost the “clipping” and the full story. If Jason – or anyone else – could help me re-locate the full story, I’d be grateful.

From my memory, the story goes something like this …

It is a story about a woman, a young woman in the mid-1940s, who began investing in stocks at just post-WWII. She was not “wealthy” or skilled (only had a high school education, as I recall), and worked her entire life as a secretary – no “high paying” jobs in her lifetime, nor did she re-marry or inherit any wealth. But she did invest whatever little she could continuously during her lifetime. The story became a “story” when, at her death (again from memory, mid/late 80s to early 90s), her estate’s net worth was some tens of millions of dollars – $20 to $40 millions, if memory serves.

A couple of parts of this woman’s story I do remember were that she led what would now be considered an exceptionally frugal lifestyle her entire life. And that one of her few “extravagances” was to personally attend – and “speak out” – at annual stockholders meetings for the companies she owned.

I also recall that her story was one I would call a true “Investor” story.

Can Jason (or anyone else) remember that story and help me re-find it? I’d be grateful.

Matt Obenhaus

Jun 8 2016 at 2:33pm

I personally thought the last few moments, where Roberts started reading some of the definitions from Zweig’s book, were the highlights of the session. I enjoyed the definition of central banks and the subsequent discussion on humility and am reminded of observations from several writers and public thinkers that goes something along the theme of the more that we gain knowledge, the more we recognize our tremendous capacity for ignorance. I particularly enjoyed Zweig’s observation that great nature is awe inspiring and humbling, and the complex, dynamic, and inscrutable market should humble us as well.

I chuckled at the discussion on the stock market game, since my high school economics class teacher ran the same game to teach us about markets. I recall out of a form of laziness and disinterest just picking all the restaurant stocks since I derived great pleasure from eating at those places. Perhaps this was about as effective as Malkiel’s Random Walk idea of throwing darts at a Wall Street Journal, but somehow I missed out on the lessons of diversifying my portfolio. Fortunately, later on in life I would have an Investments course in graduate school taught by Kenneth French, where his opening line, as he wrote on the chalkboard – 1-800-Vanguard – “I am right now going to teach you the most important thing you will learn in this class…”

JD

Jun 11 2016 at 11:31am

I still don’t quite understand the idea that not selling a ticket for $1000 should equivalent to paying $1000 for it in the first place.

Let’s say, just as a simple figure without real significance, that I earn $10,000 a month. And say I buy a Hamilton ticket for $180. Russ argues that since I can resell the ticket, its real cost is $1,000 (really, it’s 1,000-180=$820). But I probably have a use allocated for my whole salary of $10,000 – from rent and food to my magazine subscriptions and electronics – and, at some point, the Hamilton ticket. If the box office price to see Hamilton were actually $820, the additional price for me would be the 820-180=$640 worth of things already included in my budget (let’s just say it’s a laptop) I would have to give up in order to allocate the $820 for the theatre ticket. If the price is $180, and I take it without re-selling at $1000, in a sense, I give up $820, but these are *additional* $820 which I presumably value less than going to see the show – but in that case, I still get the laptop I would have had to give up were the show’s ticket $820 – and it may well be that I value that laptop more than going to see Hamilton. I think this satisfactorily answers the question of why many people would buy the tickets at a lower price and not resell it, but would not actually buy it if the ticket price were higher – they value the already allocated $820 more than the ticket, but value the ticket more than the *additional* $820.

If we reduce the amount you earn in this hypothetical to $1,000, you can see it even more clearly: if you buy a ticket and keep it, you have $820 left over for other things, but if it cost $1,000 you’d have nothing left over that month. Now, if your salary was just $1,000, you’d definitely see the potential bonus of $820 by scalping it as much more attractive, but at the same time, a person earning that much a year would be much less likely to feel like they could afford the $180 in the first place – so a person with that kind of income would be more likely to buy the tickets only to make a profit on them. But if a person with a $1,000 income actually valued the tickets enough to buy them for that purpose, without reselling them afterwards, you might say that the real cost is much higher, but clearly if the tickets actually cost $1,000, buying them would be almost impossible.

I hope this makes sense, and that someone could clarify this for me…

jw

Jun 11 2016 at 11:48am

Since Bogle wrote his famous book on index funds in 1999, your returns on the QQQ or SPY would be about 3%/yr (compounded, after inflation). If you invested in the Japanese stock market on the same date, you would have received a 0.3% return for 17 years (compounded, no inflation).

If you were unfortunate enough to have retired in Japan at the end of 1989, when everyone thought that the new, centrally planned, MITI dominated Japanese economy was the best model for the entire world, you would still be down over 50% on your initial investment 26 years later.

In the above scenario, to get those 3% inflation adjusted returns, you would have had to withstand a 63% drawdown (low from initial investment) in the QQQ and 40% in the SPY. Since the bubbles of 2000 and 2007 were even higher than March 1999, you have seen even higher peak to trough drawdowns.

ETF’s are a very good thing as far as investment vehicles go, but the buy and hold strategy espoused by Bogle in 1999 has many erroneous assumptions and cherry picked data. It is the biggest violation of the “past results are not indicative of future returns” caveat that is in every broker ad.

I have read enough of Zweig to know that he understands that buy and hold does not mitigate risk and that bigger, longer drawdowns may be out there. However, I don’t agree that the average investor should simply do the easiest thing for the street, entrust their money to them in a blameless (for the advisor) strategy and remain in ignorance of the markets. Investors should always be worried about their portfolios, and should monitor them carefully. Someday, the market won’t come back.

I do appreciate Zweig’s honesty in that he has to repeat himself, I agree that most financial opinion is very repetitive.

And someday, Zweig will understand the errors he made in his famous “Pet Rock” piece.

Finally, there is no such thing as “house money”. A dollar in your portfolio doesn’t know if it was an initial investment or a gain. This is a concept marketed by the negative sum casinos – “If I’m down, I’ll gamble until I’m up, if I’m up, I’m playing with house money so I’ll gamble.” The only consideration of gains should be the tax implications of your investments.

WilliamNV

Jun 11 2016 at 9:08pm

“…the financial industry, who effectively drove the nation into the Crash of 1929 and to some extent into the Great Depression.”

I thought the root cause of the Great Depression was the Fed holding rates down artificially to support the Bank of England in 1927. The resulting bubble caused the markets to expand and then collapse in 1929. An act that keeps being repeated by the Fed…

elan

Jun 12 2016 at 10:37am

mr zweigs conversation with his father touched me. wouldnt it be great to get more of the old scriptures into our world, everybody having his place, beeing waymore humble, attentive and serene.accepting the economists “rational” imperative as brain gymnastics in model building but not as an explanation. the issue is that this explanation/model will be adapted by the youth as an instance of truth. there are better alternatives.

jw

Jun 12 2016 at 7:05pm

Speaking of the tax implications of your investments, ticket scalping profits, no matter how small, are considered by the IRS to be a capital gain. I am sure that you are all factoring those tax payments into your calculations…

ls

Jun 13 2016 at 12:38pm

jw’s comment resonates with me because I entered the workforce in 2000. I’ve invested more or less continuously since then, buying mostly market index mutual funds and then later ETFs. 16 years later, peak to peak in the market, and I am profoundly disappointed by the returns: something around 2% yearly! (Before inflation, and not including dividends.)

Sure: my investment horizon is not up yet, but this in no way resembles the “8 percent per year” story that I was told to expect in the long term by folks like Mr. Zweig. How much longer do I have to wait to start seeing that long term return? Another 16 years? I am losing faith in this model, but for lack of a better idea I will continue to invest in the market and sector indexes.

I honestly wonder if index funds and ETFs may be defeating the invisible hand theory of the market. There is no truer definition of “dumb money” then an index fund–you’re just buying what everyone else is buying. And, if we do as we’re told (buy and hold) you never make another decision after that. How is this going to affect the invisible hand? What percent of total investment has to be “smart money” in order for the market to continue to work properly? And what percentage of the gains should we expect to go to the smart money versus the dumb money investors?

Thanks for another enjoyable episode of Econtalk!

jw

Jun 14 2016 at 7:20am

ls,

I know more than a few young people who have the same questions about the current truisms of investing. Unfortunately, you are part of a great experiment with a major flaw. You have been told all of your life that buy and hold is the only way to wealth because that is what has worked in the past. This is a classic example of in sample testing vs out of sample testing. People looked at the past, saw that buy and hold was good, and wrote books about it without determining whether it could hold up in the future. They also ignored risk, saying that over a long period of time, risk (usually defined as volatility, but that is not risk) could be ignored as buy and hold won out.

But we no longer live in the 40’s, 50’s, 60’s etc. We live in a brand new world where central banks affect every financial decision and the regulations that US businesses have to deal with are multiple orders of magnitude greater than decades of returns that buy and hold theory is based upon, and debt has skyrocketed. Sure, there are still successful companies, but the theory says that you can’t pick them anyway, so don’t try.

Right now, your generation is faced with historically low bond yields and high bond prices and a stock market that by many metrics is over valued and at a nearly historic length bull run. And a misguided Fed who is openly trying to discourage savings. I do not envy your situation and I apologize for not being able to prevent others in my generation from squandering your future.

Investing is very difficult and there are no easy answers, but learning can be a significant competitive advantage over those who simply follow the crowd. And if you enjoy learning and competing, it beats the heck out of any video game. Be careful out there.

Jeff Guernsey

Jun 14 2016 at 6:16pm

Appreciate the conversation that Russ & Jason had on this podcast.

I teach a Personal Finance class at the University level and use a stock market simulation, so the segment about stock market games got my attention. I laterfound Jason’s article about the Capital Hill Challenge [http://blogs.wsj.com/moneybeat/2015/05/08/stock-market-101-teaching-the-wrong-lessons/] Yikes! Allowing high school students to borrow on margin and simply encouraging the best returns (no acknowledgement of risk) – NOT a good idea.

I too don’t like the short-term nature (semester-long) of the stock market simulation, as investing should be long-term. However, the simulation does get students familiar with stocks, the mechanics of buying & selling, and how many factors (outside of their control) can influence a stock price. I set parameters so that students can not borrow on margin.

I would take issue, however that a simulation like this is gambling. Gambling is tails I win, heads I lose everything. Even the Capital Hill Challenge, with its faults, does not rise to that level.

Thanks again for a fascinating podcast. Keep ’em coming Russ!

[Full URL substituted for shortened URL. Please use full URLs so people can see where they are going. Thanks.–Econlib Ed.]

Trent

Jun 16 2016 at 8:47am

JD,

The $1,000 example is an illustration of opportunity cost: What are you giving up by buying X or doing Y?

Let’s say that you won 2 tickets for Hamilton that you could resell for $1,000 each. By going to the show and using the tickets, you’re giving up what you could have bought with the $2,000 that you would have received by selling the tickets.

So you effectively “spent” the $2,000 from your winning the tickets on those tickets, in terms of opportunity cost. You just didn’t have the actual transaction of selling your 2 tickets for $2,000, then buying them back for $2,000…..instead of, say, making an extra $2,000 mortgage payment, or buying a $2,000 laptop, or putting $2,000 in your savings account.

Does that help?

jw

Jun 16 2016 at 10:00am

JD,

It is also an example of utility theory. Oprah wouldn’t think twice about selling the tickets for a measly $820 gain, the value of the show exceeds the scalper ticket price.

Obviously, Russ and Jason value the utility of the scalper profits enough to consider the alternatives.

Charles

Jun 16 2016 at 11:08am

It could be rational to keep the tickets if you have a decreasing marginal utility of money.

You might have budget/liquidity constraints which would prevent you from being able to spend $1000/ticket, but you might not value the profit.

Comments are closed.