Episode Transcript

Olivia Allen Price: We start today’s episode on a beautiful, clear and sunny day back in 2018.

Olivia Allen Price: Could you tell us where have we brought you today?

Lori Bodenhamer: We’re on the western side of Alameda Island and we’re very close to … I see the Port of Oakland. We’re in the Hanger One Vodka Area. I think it’s called Spirits Vodka now?

Olivia Allen Price: I’m standing in front of a giant sign that says “Warning Restricted Area: Authorized Personnel Only” with this week’s question asker.

Lori Bodenhamer: My name is Lori Bodenhamer. I’ve lived in San Francisco for about 20 years.

Olivia Allen Price: We’ve come to Alameda to check out a peculiar piece of land that Lori noticed.

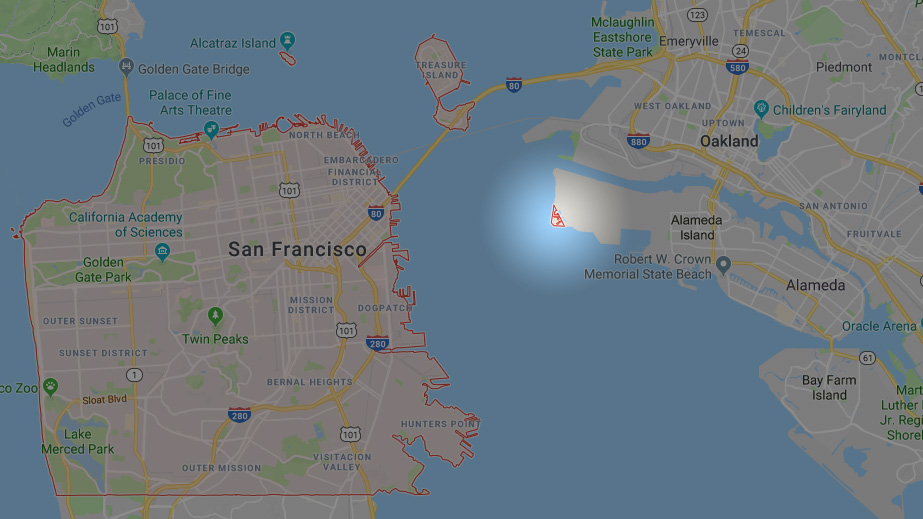

Lori Bodenhamer: My little shortcut to get to the Google Maps — I just type in “SF Map,” and then Google pops up and it outlines San Francisco in red and noticed there were some bits of red in Alameda.

Olivia Allen Price: The border of San Francisco should be simple. You’ve got water on three sides and a straight line along the southern edge. But … not so!

Lori Bodenhamer: I wondered why there’s a little sliver of San Francisco on the western edge of Alameda.

[Theme music playing]

Olivia Allen Price: This is Bay Curious, the show where we answer your questions about the Bay Area. I’m Olivia Allen-Price. Today we travel from 19th century Spanish California to a World War II-era Navy station in Alameda. All to figure out why the heck San Francisco has jumped the bay. This episode first aired in 2018 and we’re reairing it today because it tells one of the wackier histories of land ownership we’ve found. Stick around.

We asked Bay Curious reporter Ryan Levi to tackle this one.

Ryan Levi: It looks like a little right triangle, just a 30-some acre sliver at the very western tip of Alameda Island. It’s all the way across the bay from San Francisco, but somehow, it’s still a part of S-F.

And honestly, I thought figuring out how that was possible would be pretty easy. Just call someone up at the city and get the answer.

So I start calling people.

[Music playing]

I try the City Administrator’s office [sound of voicemail]. They don’t know and say I should email the Department of Real Estate [typing]. They’ve also got nothing. So I reach out to the Department of Public Works where finally we have a breakthrough.

I get a tip about a court case from 1964 that’s somehow connected to our sliver, but records from that far back aren’t going to be digitized so my only option is to go find it for myself.

Ryan Levi: Are you where I check in?

Front desk worker: Yes.

Ryan Levi: The National Archives Building in San Bruno is kind of hidden away behind the Tanforan mall and a housing development. I expected it to be kind of dungeon-y, but it’s got lots of windows and natural light and wooden tables set up for researchers. Feels like a library.

National Archives worker: This is case 35276.

Ryan Levi: They set me up at one of the tables with this gray file box filled with three folders bursting with documents.

National Archives worker: Looks like it’s oversized maps and stuff.

And when I start going through them all, I realize that this case goes back a lot further than I thought. All the way back to when California was part of Spain.

[Music playing]

It starts in 1820 with a guy named Luís Maria Peralta.

Dennis Evanosky: He served as a soldier for the Spanish government.

Ryan Levi: Dennis Evanosky is the publisher of the Alameda Sun newspaper and until recently was the president of the Alameda Museum. He says Peralta caught the attention of the Spanish government when he secured the release of a group of priests who had been kidnapped from Mission San Jose and taken to the Central Valley.

Dennis Evanosky: As a thank you gift, he got a land grant that stretched all the way from El Cerrito down to San Leandro.

Ryan Levi: Basically they give him the entire East Bay, even though Native Americans like the Ohlone and Bay Miwok had already been living there for centuries. But Spain gives Peralta the land, which he then splits among his sons.

Fast forward 31 years. California is now part of the United States and one of Peralta’s sons, Antonio, is looking to unload some of his land.

Dennis Evanosky: Antonio was delighted to find out that there were actually Americans that were willing to pay him.

Ryan Levi: This was because squatting was a big problem in the state’s early days … so Peralta was thrilled when two men…

Dennis Evanosky: William Worthington Chipman and Gideon Aughinbaugh.

Ryan Levi: Made an offer on 160 acres of Peralta’s land where they established the town of Alameda.

But Peralta had a problem.

[Music playing]

His land was in the U.S. now and it would take the government more than 20 years to recognize his claim with a patent.

Dennis Evanosky: Unfortunately, by then yes the land would have belonged to him had he not sold a lot of it. And also by then Aughinbaugh and Chipman were both gone.

Ryan Levi: So Peralta, Chipman and Aughinbaugh had all left Alameda by the time the government finally got around to affirming Peralta’s claim in 1874 and issuing him that patent for the land.

Voice over actor: Now Know ye, that the United States of America in consideration of the premises [voice fades out].

Ryan Levi: But the language in that patent, it’s really important for our purposes, and here’s the part you have to remember: [Music starts] the patent includes the piece Peralta sold to Aughinbaugh and Chipman and it says that its western border is…

Voice over actor: “Along the Bay of San Francisco, at the line of ordinary high tide.”

Ryan Levi: “Line of ordinary high tide.” Remember that.

Archival tape: On December 7, 1941 Japan like its infamous Axis partners struck first and declared war afterward…

Ryan Levi: World War II comes to Alameda. Within months of Japan attacking Pearl Harbor, the brand new Alameda Naval Air Station becomes the launching site of the first major bombing raid on Japan.

Archival tape: The United States aircraft carrier Hornet … part of a taskforce steaming into Japanese waters is now revealed as the secret base from which American plans first bomb Tokyo.

Ryan Levi: After the war, the station continues to grow by filling in San Francisco bay with new land. So it was totally normal when the Navy claimed about 50 acres of the bay in 1956 to expand the base.

But what happens next is not normal.

[Music playing]

When the Navy adds this landfill on, it crosses over the invisible line underneath the bay that marks the border between San Francisco and Alameda. Once filled in, this tiny sliver of Alameda Island is now technically in San Francisco.

But no one really cares that this underwater border has been breached. What people do care about is who gets paid for this land the Navy is taking.

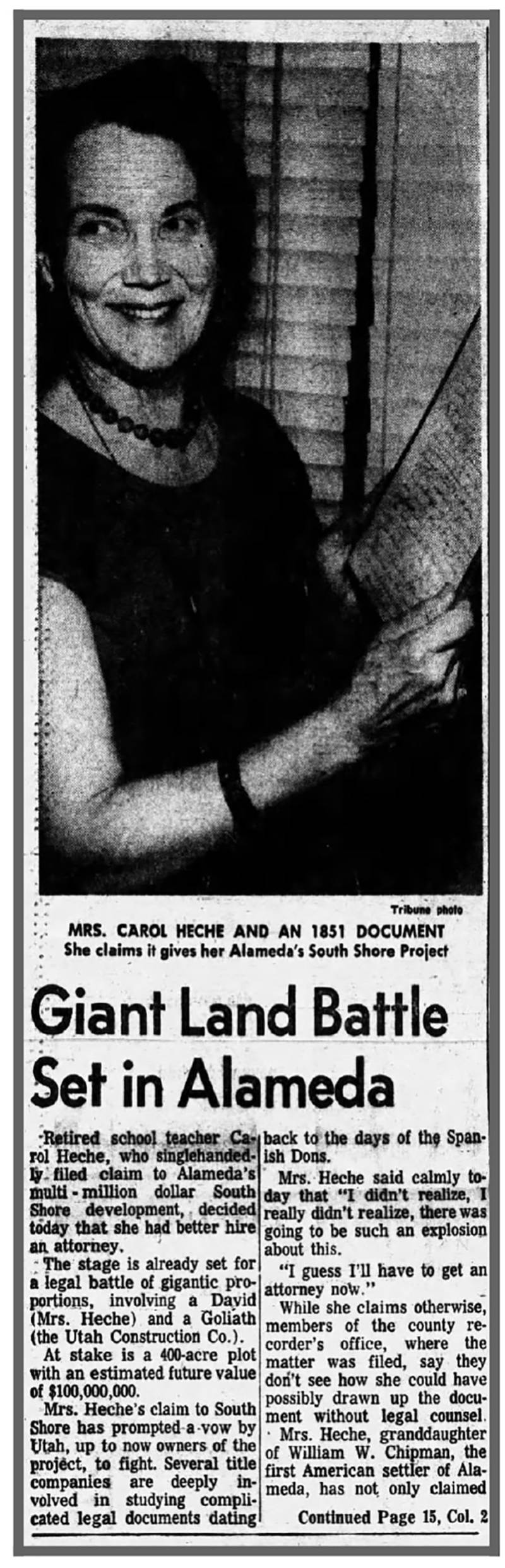

And that’s when two new players enter the arena: Elinor Petersen and Carol Heche.

George Gunn: Mrs. Heche … she was a leading member of a museum when it was founded.

Ryan Levi: George Gunn is the curator of the Alameda Museum.

George Gunn: Everybody knew that she was the granddaughter of Chipman.

Ryan Levi: That’s William Chipman, one of the men who bought the land from Antonio Peralta to establish Alameda back in the 1850s.

George Gunn: That was their one claim to fame.

Ryan Levi: It was also how Heche and Petersen claimed ownership and demanded payment from the U.S. government for the part of the bay taken by the Navy to expand the air station.

George Gunn: She was very proud of their heritage and she was the historian of a family. She claimed that their property extended out into into the bay.

Ryan Levi: She made this claim based on the original Peralta land grant — the one given by Spain in 1820 — which she and Petersen said extended into the quote “deep waters of San Francisco Bay.”

But here’s the rub. That original Spanish land grant may have talked about “deep waters,” but remember that 1874 patent? It set the borders “along the Bay of San Francisco, at the line of ordinary high tide.” High tide is not the same as deep waters.

And when the women took their case to court, transcripts show the judge was only interested in the patent, the U.S. definition of the borders. Here’s one exchange between the judge and Petersen, who represented the women in court.

[Actors’ voices]

Judge Alfonso Zirpoli: The only question involved is whether or not your land comes within this patent.

Elinor Petersen: It does.

Judge Alfonso Zirpoli: If it does, you are entitled to judgment in your favor.

Elinor Petersen: Absolutely does.

Judge Alfonso Zirpoli: If it doesn’t, you are not.

Elinor Petersen: It absolutely does.

Judge Alfonso Zirpoli: I think it is as simple as that.

Elinor Petersen: It does, absolutely, every bit of it.

Ryan Levi: But the judge disagrees and rules against Heche and Petersen. They appeal the case, but to no avail.

In the end, the Feds do end up paying for the land. Just shy of 14-thousand dollars to California. And the women? They get nothing.

[Sounds of walking on gravel]

Lori Bodenhamer: It’s so peaceful here. And what a perfect day.

Olivia Allen Price: We’re back on present-day Alameda Island with our question asker Lori looking across the bay at the San Francisco skyline. And yet…

Larry Janes: So you’re in San Francisco now.

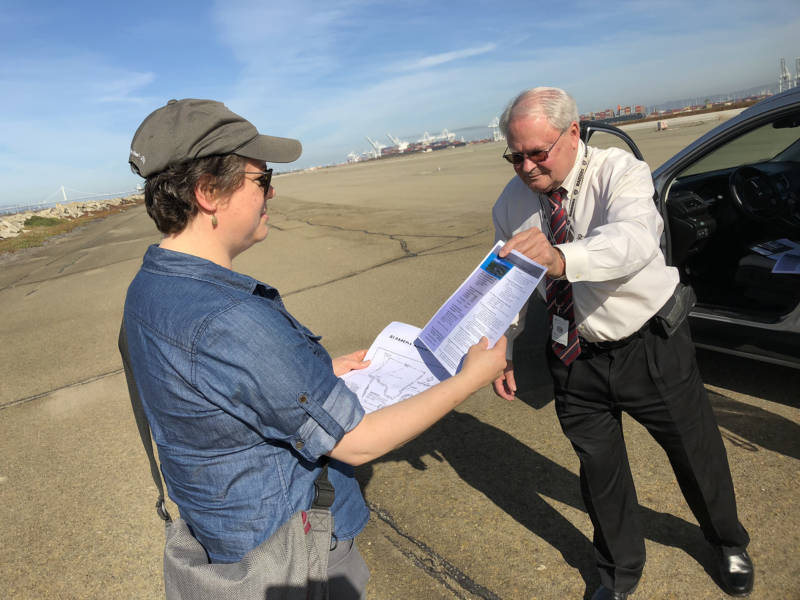

Ryan Levi: That’s Larry Janes. He’s with the Department of Veterans Affairs which now owns the sliver, and he’s taking us on a tour of this restricted area.

Larry Janes: This pond that we’re looking at here, in the summertime you’ll have several hundred Caspian terns that come here.

Olivia Allen Price: After the Navy closed the air station in the late ’90s, it gave more than 600 acres of it to the VA to build a new hospital and national cemetery.

Larry Janes: From the VA’s perspective it really doesn’t matter if it’s Alameda or San Francisco County it’s federal property.

Lori Bodenhamer: What logistics does that mean? Like for example if a crime was committed where’s the jurisdiction?

Larry Janes: We actually have a contract with East Bay Regional Park District Police. And we have our own VA police as well and we work with the Alameda police so if we needed backup from Alameda we could go to them as well.

Olivia Allen Price: But San Francisco is out of the picture.

Larry Janes: I mean they can come over if they want but it’s a little bit of a distance for them, right?

Ryan Levi: Neither Alameda nor San Francisco zone the sliver and the VA has promised not to develop it because it’s home to an endangered bird species … called the California Least Tern.

Larry Janes: In order to ensure their well-being, we had to leave them a buffer zone.

Ryan Levi: The VA is talking to the city of Alameda about putting in a recreational trail that would hug the coastline around the sliver. So maybe one day soon, you too can walk from Alameda right into San Francisco and stand on land that was disputed all the way back to the King of Spain.

[Theme music playing]

Olivia Allen Price: That was Bay Curious reporter, Ryan Levi.

Thanks to Lori Bodenhamer for asking this week’s question.

We are sending our January newsletter out next Wednesday – that’s January 10. In it, we’ll answer a question from listener Mandy Y.: “Who put up the large letters ‘South San Francisco The Industrial City’ on a hillside over the town? Why is it there?” If you’re curious, be sure you’re subscribed to get the answer at BayCurious.org/newsletter.

Our show is produced by Katrina Schwartz, Christopher Beale and me, Olivia Allen-Price.

Lori Bodenhamer: Bay Curious is made in San Francisco at KQED.

Olivia Allen Price: And we’re actually in San Francisco as we are making it today but we’re on Alameda Island. It’s weird. I’m not going to get over it. It’s just weird. It’s cool.

Olivia Allen Price: Thanks to Jessica Placzek and ENGINEER for their work on this episode. Additional support from Jen Chien, Katie Sprenger, Cesar Saldana, Maha Sanad, Holly Kernan and the whole KQED family.

We’re back next week with a new episode. I’ll see you then!