When Avalon Theatre opened on Wednesday, May 29, 1929, as part of chewing-gum tycoon William Wrigley Jr.’s Catalina Casino, the festivities — which included marching bands and a screening of Douglas Fairbanks’ The Iron Mask — attracted thousands of curiosity seekers as well as various Hollywood stars who trekked out for the spectacle to the small town of Avalon, perched on the southeastern end of Santa Catalina Island.

But the most lavish and beautifully detailed movie palace in Southern California — and quite possibly the entire world — went out with a virtual whimper during its final week of regular screenings, ending a 90-year tradition of showing first-run films. Although Avalon Theatre, located on the ground floor of the imposing Catalina Casino, can still be visited on guided tours and will open its doors sporadically for special events, there was a palpable feeling of sadness in the grand old theater during one of the last screenings, on Sunday evening, December 29, two nights before the final screening on New Year’s Eve.

The theater fell victim to a changing economy and the changing habits of many moviegoers, who nowadays largely prefer to stream films online. But the concept of having an elaborate 1,154-seat cinema in a small island town with a resident population of about 3,700 people was always a bit of a mad idea. There was a time when well-heeled movie fans enjoyed taking a boat, helicopter or plane over to the island to revel in the stunning layout of the theater, ensconced in the tall, white, circular Catalina Casino (which houses a ballroom and was never a gambling casino) with architects Sumner Spaulding and Walter Weber’s fusion of Art Deco and Mediterranean Revival styles and adorned both inside and out with large, fantastic, fairy tale–like murals by John Gabriel Beckman.

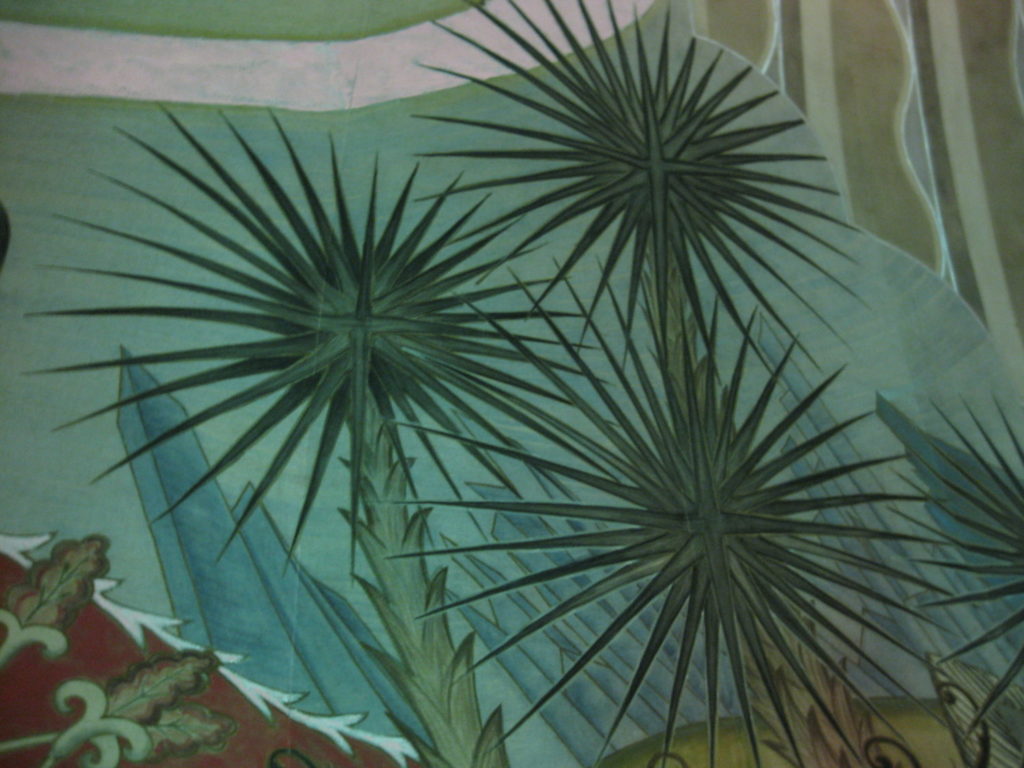

Detail of John Gabriel Beckman’s interior mural (Falling James)

Avalon Theatre and its underused upstairs neighbor, Catalina Casino, might no longer be economically viable according to Catalina Island Company, the private nonprofit company with some of Wrigley’s heirs that runs and owns much of the island. But Catalina Casino is the most iconic structure in Avalon, and Avalon Theatre is so unique that film fanatics from all over the world plan trips just so they can experience a film inside the circular space. Moreover, the theater is one of the only gathering places and hangouts for locals on the island, where most activities and businesses cater mainly to tourists.

Even though it was the off-season, a moderate amount of mostly international tourists rode the ferry over for the December holidays and strolled through the streets of Avalon on a cool, partly sunny day. Big white clouds spilled over the green mountains that border the west side of town, but Avalon didn’t really seem to come to life on Sunday until the sun went down and lights began to illuminate the steep sides of the casino.

“It’s beautiful,” a young woman murmured aloud as she walked in a daze through the theater’s lobby, which resembled a posh private lounge with its walnut paneling and its red and orange–painted ceiling emblazoned with golden stars and dangling florid, ornately designed black iron lamps. Nearby, a mother lamented to her daughter, “This is the last time we’re going to see a movie here.”

Organist Jon Tusak (Falling James)

More stars began to twinkle inside the theater as the tiny lights inside the constellations decorating the vast universe of the Avalon’s high, expansive white ceiling flickered to life. About an hour before the nightly 6:30 p.m. screening, organist Jon Tusak sat down at the theater’s original Page organ by the side of the stage and began pumping out a free-flowing, almost jazzy instrumental mash-up of “If I Only Had a Brain,” the always poignant “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” and other tunes from The Wizard of Oz. As Tusak kneaded the keys and pulled the organ’s stops, birds in the walls and ceiling of the theater chirped along excitedly in a merrily demented sing-along.

Other colorful, long-plumed birds were frozen in midflight — along with playful, mythical, Seuss-like blue antelopes, quizzical monkeys, a naked archer, brooding hooded monks, and a storm-tossed galleon amid tumultuous ocean waves — in Beckman’s dazzling and trippy mural, which was painted on canvas and wrapped around the tall white walls of the theater’s interior.

By the time Tusak finished playing and the room darkened, there were about 40 to 60 people scattered around the theater. At the Sunday screening, the night’s feature was run without fanfare. For obvious reasons, there were no previews of upcoming films. There was also no opening short film or any host introducing the main feature or commenting on the sad occasion. The final feature film, Jumanji: The Next Level, might have seemed like a pedestrian choice given Avalon Theatre’s extensive history, but it was actually in keeping with the mainstream, populist fare the theater has been showing for the past few decades, apart from an occasional film festival or special screening.

Avalon Theatre’s defense shelter (Falling James)

With a relatively muted Jack Black, a half-hearted Kevin Hart, a wan Danny DeVito, a distant and leaden Dwayne Johnson, and a comparatively game and attentive Karen Gillan, the latest Jumanji installment was a fairly weak, paint-by-numbers sequel assembled by mercenaries and robots. But it was just corny and cartoonish enough to make for a passing distraction in the background since, on this night, the theater itself was the main attraction. If anything, this Jumanji made for a better backdrop than some tense interior drama or claustrophobic thriller — even if its special effects and array of ferocious wild animals paled in comparison to Beckman’s magnificent creatures on the walls. During the film’s brighter scenes, such as when the characters find themselves in a sunny desert, it was all too tempting to look away and use the available light to marvel over the theater’s mural instead.

The theater contains many secrets. Earlier, an insider pointed out where a fire hose was hidden in the fancy lobby as well as the location of a secret door just behind the curtain at the back of the theater, which led to a large, hidden space containing dozens of barrels of food and water. (The theater still serves as Avalon’s civil-defense shelter.) Avalon Theatre was the first cinema built for films with sound, and numerous Hollywood figures and celebrities — from a pre-fame Marilyn Monroe, a onetime resident of Avalon, to Harry Houdini, Charlie Chaplin, Paulette Goddard, Jacques Cousteau, Errol Flynn, Charles Laughton and Louis B. Mayer — worked and played on the island.

What happens next for Avalon Theatre remains unclear. “As for the theater’s future, the Island Company plans to continue taking great care of the facility, sharing it with others and making it available for various events,” writes Kristin Leigh Metcalfe, senior director of marketing and communications with Catalina Island Company. “We are working with interested parties on viable proposals for how to continue to show films at the theater.”

Exterior of Avalon Theatre (Falling James)

There have also been rumors that Avalon Theatre might be used as a concert hall, even though the upstairs ballroom is already empty much of the year. The downstairs theater might make for a spectacular music setting along the lines of such repurposed downtown L.A. movie palaces as the Theatre at Ace Hotel and the Orpheum Theatre. But it would require a change in vision by the building’s stewards, who have historically favored nostalgic big bands and light jazz instead of more adventurous and diverse music. Catalina Ballroom — and Avalon in general — is not a very rock & roll place.

In many ways, it still remains the Island That Time Forgot. Smoking was banned in the ballroom, and the Wrigley family didn’t allow alcohol in the building until 1949, according to Hadley Meares’ 2014 KCET.org article “The Catalina Casino: The Magic Isle’s Art Deco Pleasure Palace.” Locals generally have to take a ferry to the mainland if they want to hear live performances of music created after World War II (apart from infrequent cover bands in Avalon’s tourist bars).

Detail of John Gabriel Beckman’s interior mural (Falling James)

With its picturesque seaside setting and cute cottages, and with tourists and residents alike getting around on bicycles and golf carts (there are only a handful of larger vehicles on the island), Avalon resembles Portmeirion, the Welsh town that was portrayed as The Village, the quaintly ominous and rigidly controlled setting of the 1967 British TV series The Prisoner. While getting to and from Avalon isn’t quite as harrowing as it was for Patrick McGoohan attempting to escape The Village, it has required some effort and planning for a mainlander to see a film at Avalon Theatre. In recent years, there has been only one screening per day, usually at 6:30 p.m. During off-season times of the year, the last ferry from Avalon to the mainland departs at 7:30 p.m., making it impossible for day trippers to catch a feature-length movie.

And yet, as one leaves the island at night, moving over the dark water with the orange lights of Avalon sinking back into the horizon, it is Catalina Casino that lingers the longest, both in sight and memory. It is sobering to realize that, for the first time in nearly a century, Avalon Theatre is no longer a working, vibrant and real cinema with regular screenings but is instead a magnificently sculpted relic of a time when rich men still commissioned the construction of monumental edifices in unlikely locations.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting LA Weekly and our advertisers.