When Feathers Were the Treasures of the Rainforest

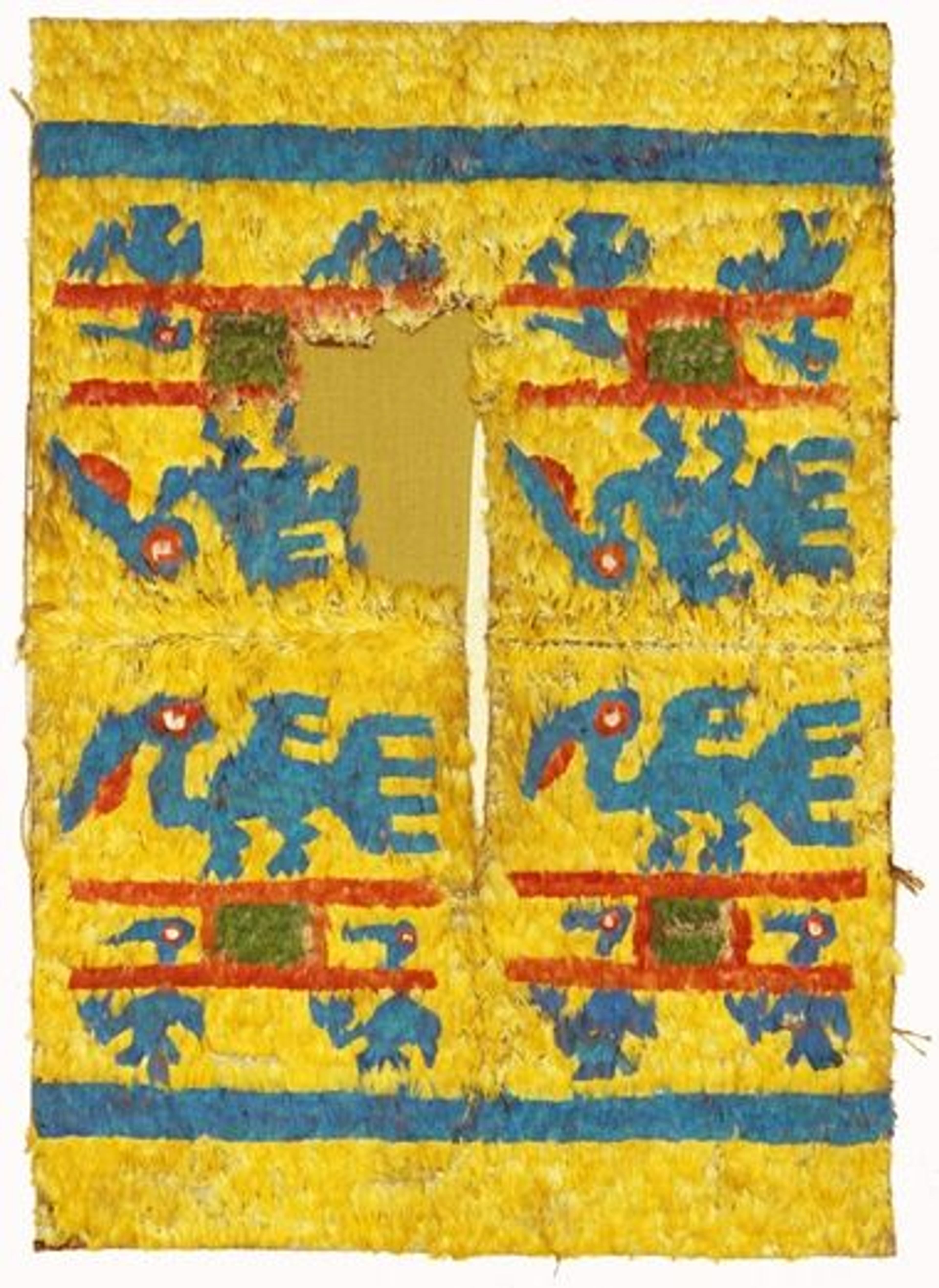

Feathered panel (detail), A.D. 600–900. Peru, South Coast. Wari. Feathers on cotton, camelid hair, H. 29 1/4 x W. 83 5/8 in. (74.3 x 212.41 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.470). Photo by the author

Look up! Nowadays flocks of birds fly far below the contrails of jets efficiently moving humanity around the world at thirty-five thousand feet. Most of us think nothing of "flying" in order to move quickly from destination to destination, yet the lure of moving through the air in the manner of a bird continues to have a strong hold on the mind. Humans persist in developing the means to control individual flight, as witnessed by courageous (some would say insane) adventurers gliding silently through the air while encased within technologically advanced wingsuits.

In ages past, birds in flight also had an enduring hold on the human imagination. Back when birds ruled the sky, flight was given to humans through transformational stories, dreams, and hallucinations. Remembered oral histories and ethnographic documentation indicate donning a feathered garment or accessory could convey a bird's power of flight to its wearer. Additionally, scholars speculate that the role of featherwork within complex ancient societies was to please the gods with their beauty, and to distinguish the wearer from his or her attendants and supporters.

Feathers have historically been admired and put to use by humans around the world, but in the Americas feathers were—and in remote pockets continue to be—used as luxurious adornment to an extreme found nowhere else. Amazingly, the arid coasts and frigid mountains of Peru, Chile, Bolivia, and Argentina have preserved several millennia's worth of material culture, including ancient featherworks from many long-forgotten regional cultures. Unfortunately, feathers, although robust on the living bird, deteriorate over time, and the passage of hundreds, if not thousands, of years have altered a majority of featherworks for the worse. Those excavated by archaeologists are often fragmentary, wrinkled, and soiled, so while they prove to be invaluable documents of the past, they are rarely exhibitable in a fine-arts museum.

Feathered panel (1979.206.470)

We are exceedingly fortunate that the exhibition Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through May 28, brings together a small but thoughtful selection of featherworks in near-pristine condition—eye-catching objects as luminous as the gold works that surround them in the galleries. Even though the locations at which they were found and their times of manufacture are separated by great distances and centuries, from an aesthetic point of view each of these objects reveals the intrinsic beauty of featherwork, the skill of the feather workers, and the significant ritual role of feathered textiles in Precolumbian culture.

Peoples of ancient South America lacked a written language, which leaves scholars needing indirect evidence to discover the purposes and meanings of these works. Although Precolumbian design iconography differed over time and space, as evidenced by the examples in the exhibition, the craft of featherworking seems to have remained a homogenous yet multifaceted tradition until the arrival of the Spanish in Peru in 1532. For instance, all of the Andean featherworks presented in Golden Kingdoms have a lightweight, flexible woven foundation to which strings of feathers are tied. Information gleaned from analyzing technical differences in similar materials of featherworking can be aggregated with iconographic and available provenance information to produce a cultural profile that will suggest the time and place of manufacture.

Detail image of yellow feathers attached to strings. Photo by the author

Author's drawing of feathers hand-knotted onto strings

The featherworks featured above employ foundation fabrics woven from cotton yarns in a simple over-and-under weave (plain weave), but the technical details of yarn creation, coupled with the weaving methodology, result in fabrics that are visually and tactilely distinguishable from one another. These details, in turn, suggest the probable cultural affiliation of the weaver. So far, research into the methodologies of stringing feathers indicates that the Precolumbian specialists who tied feathers onto the strings, either individually or in groups, always created feather strings of a single color and similar size. When the design demanded a color change, the feather string was cut and a different string containing the appropriate color was begun.

As with weaving, the methods of tying the feathers onto cords vary: some use a single thread, others two. The feather strings are then laid onto the fabric, like shingles on a roof, starting at the bottom and moving upward, row by row, and stitched into place. More closely spaced rows result in a more plush fabric. Since the overall designs are created from thousands of tiny feathers, these creations are also referred to as feather "mosaics."

A scarlet macaw (left) and a blue-and-yellow macaw (right). Photo by Quinn Dombrowski

Neotropical ornithologists have identified some of the birds whose feathers were used in these creations. Generally the brightly colored feathers come from birds living in the rainforests at lower altitudes along the eastern slopes of the Andes and into the vast Amazon River basin. The distinctive size and shape of the iridescent blue-green and hair-like yellow feathers (see the first image in this post) on all the examples have been identified as from the blue-and-yellow macaw (Ara ararauna). The orange-red feathers are often identified as being from the scarlet macaw (Ara macao), although other species are also possible. Green feathers can be harvested from many species of Amazon parrots. Black and white feathers are difficult to identify, for the obvious reason that many birds sport such plumage and, additionally, feather workers sometimes trimmed the feathers in order to sharpen the design, thus destroying the distinctive silhouette.

Tabard with lizard-like creatures, A.D. 500–750. Peru, South Coast. Nasca. Feathers on cotton, H. 23 x W. 30 1/2 in. (58.4 x 77.4 cm). Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Fund (60.44.3). Photo by Katherine Wetzel. Image © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

The earliest feathered mosaic on view in Golden Kingdoms is a short, wide garment called a tabard, which is open at the sides with a center opening for the head. Both the make-up of the cotton foundation fabric and the feathered iconography point attribution to the Nasca culture, which flourished along the south coast of Peru during the first half of the first millennium A.D.

In earlier times and cultures, feathers were infrequently used and sparingly applied to accessories and garments. During the dawning centuries of the common era, "pictorial" mosaics created from feather strings seem to have been developed within the Andes, although the geographic location(s) of this development is unknown. This garment features blue and orange-red creatures or patterns, outlined in black, on a brilliant yellow ground. Such feathered garments, perhaps augmented by golden accessories, must have created quite a visual display. In the bright equatorial light, the yellow feathers would have shimmered with each movement, vivifying the entire ensemble and conferring upon the wearer a superhuman status.

Nine feathered panels, A.D. 600–900. Peru, South Coast. Wari. Feathers on cotton, camelid hair, H. 81 1/2 x W. 241 3/4 in. (207 x 614 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.464, .466–.473)

An impressive ensemble of nine blue-and-yellow feather panels from The Met collection is the largest installation in the exhibition (above). These panels—which are believed to have been part of the cache of ninety-six similarly worked pieces that were discovered in 1943 in the Churunga Valley in the department of Arequipa, at an ancient ceremonial or burial site known as Corral Redondo—are among the most visually powerful and enigmatic works from Precolumbian Peru. Accidentally discovered and subsequently unearthed by local workers, these panels were said to have been stored in large ceramic vessels decorated with Wari-style imagery. Carbon-14 dating of four of The Met's panels has dated them to the seventh to ninth century A.D., well within the period of Wari influence in the southern highlands.

Although we have chosen to display these panels in a checkerboard arrangement, their original purpose is unknown. The majority of examples that are known to exist in museum and private collections are similarly sized and most feature an identical geometric design, which suggests they were meant to be appreciated as an ensemble. The construction materials and methods used to assemble the parts are also identical. The majority of the long, narrow cotton panels have had their height and width divided at the center into equal parts, thus creating four congruent rectangles of either blue or yellow feathers of the eponymous macaw. As viewed, the top left and lower right are always blue, with yellow feathers filling the remaining quadrants.

While we don't know the significance this bird held in the minds of these ancient peoples, it is tempting to understand the contrast between the darker blue dorsal and the bright yellow ventral feathers as signifying duality: light and dark, day and night, sun and moon, man and woman, etc. The panels were then finished by adding a narrow woven band of camelid (alpaca or vicuña) fibers and two three-strand braided camelid cords. These parts were stitched into place at the top and sides.

Left: Tabard with pelicans, A.D. 1200–1470. Peru, North Coast. Chimú. Feathers on cotton, H. 38 9/16 x W. 26 3/4 in. (98 x 68 cm). The Textile Museum, George Washington University Museum, Washington D.C. (T.M.91.395)

The final Peruvian featherwork in the exhibition (left) is a petite tabard whose iconography and fabrication methods indicate it was created within the Chimú cultural sphere, which flourished on the North Coast from about 1200 to 1470 A.D., when it was absorbed into the expanding Inca empire. The pelt-like featherwork on this garment is particularly thick and luxurious. Like the Nasca example described above, the garment has a neck slit and is open at the sides; unlike the Nasca tabard, however, two identical images of proud birds—heads held high, bearing a pelican on a litter—would be visible, on the face and the back, when worn.

Also different from the earlier featherworks in Golden Kingdoms, the pictorial imagery is highly programmatic, and in that respect it echoes the imagery found on Chimú ceramic vessels and metalwork. (In this case, suggesting a particular story or myth, perhaps involving seabirds.) The pelican with its wings held high exudes power and confidence, although the exact meaning might always remain just beyond our grasp.

Unlike the situation in Mexico, where the skilled feather workers turned their talents toward the greater glory of the Christian god of their conquerors (see, for example, the magnificent Mass of Saint Gregory in final gallery), Andean featherworking went into a steep decline after the fall of the Incas. In the early seventeenth century, concerns about apostasy led Catholic missionaries to include "inspectors," whose single-minded purpose was to ferret out and destroy lingering paganism among the indigenous people. Perhaps the craft of featherworking could not be separated from the worship of the ancient gods and so was driven out of existence. Despite this suppression by colonialist forces, however, the art of featherworking in the rainforests east of the Andes and in the Bolivian highlands—likely a shadow of its former glory—lives on today.

Resources

Arriaga, Pablo José de. The Extirpation of Idolatry in Peru [1621]. Translated and edited by L. Clark Keating. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press, 1968.

Cobo, Bernabé. Inca Religion and Customs [1653]. Translated and edited by Roland Hamilton. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1990.

King, Heidi, ed. Peruvian Featherworks. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2012.

King, Heidi. "The Wari feathered panels from Corral Redondo, Churunga Valley: A Re-examination of Context." In Ñawpa Pacha, 33:1 (2013), 23–42.

Pillsbury, Joanne, Timothy Potts, Kim N. Richter, eds. Golden Kingdoms: Luxury Arts in the Ancient Americas. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum and J. Paul Getty Research Institute, 2017.

O'Neill, John P. "Feather Identification." In Costumes and Featherworks of the Lords of Chimor: Textiles from Peru's North Coast, by Anne Pollard Rowe. Washington, D.C.: The Textile Museum, 1984.

Related Content

Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas is on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through May 28, 2018.

See more digital content related to Golden Kingdoms, including a walkthrough of the recent exhibition in English and in Spanish.

Read more articles in this exhibition's blog series.

View a high-resolution gigapixel image of The Mass of Saint Gregory, a monumental sixteenth-century painting on view in this exhibition composed primarily of bird feathers.

Purchase a copy of the exhibition catalogue in The Met Store.

Christine Giuntini

Conservator Christine Giuntini is responsible for textile and organic artifact conservation in the Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas. She has created or refined the mounting and exhibition techniques for flat and complex artifacts in over thirty museum exhibitions. Her research focuses on the study of materials and methods of manufacture of African and Indonesian ethnographic textiles; archaeological feather works and fabrics from South America; and, composite works from Africa, Oceania, and the New World. She has contributed to the Museum's publications, including technical essays for The Essential Art of African Textiles: Design without End (2008) and Peruvian Featherworks: Art of the Precolumbian Era (2012).