What Is the Dow Jones Industrial Average?

Recent membership changes highlight confusion around the famous index.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average, also known as the “Dow,” shook up its constituents earlier this week. Cloud computing and software provider Salesforce.com CRM replaced oil giant Exxon Mobil XOM. Biotech leader Amgen AMGN took the place of drug manufacturer Pfizer PFE. Honeywell HON, an industrial manufacturer, replaced Raytheon Technologies RTX, a defense contractor.

These changes come after Apple’s AAPL 4-for-1 stock split, which dropped Apple’s share price by 75%. Because the Dow is a price-weighted index (we’ll discuss this below), Apple, after its stock split, has less weight in the index. To maintain the technology sector weighting, the Dow had to make some adjustments.

Membership changes to the Dow aren’t very common. What do these changes mean for investors?

A Brief History of the Dow In 1884, Charles Dow and Edward Jones, co-founders of The Wall Street Journal, created the first U.S. index, the Dow Jones Railroad Average. This index consisted of the largest railroad companies to measure their economic impact. Because of that index's limited popularity, Dow and Jones created the Dow Jones Industrial Average in 1896; this is what we now know as the "Dow." It was made up of the largest industrial companies in the United States that had monopolies in their respective industries: sugar, tobacco, oil, and rubber.

The Dow’s current form is based largely on changes during the 20th century. In 1916, the index went from a collection of 12 stocks to 20. In 1928, it increased to 30 stocks, where it remains today. For the first half of 20th century, the Dow remained largely focused on industrial stocks. However, in the second half of the century, more nonindustrial stocks entered. McDonald’s MCD and Coca-Cola KO were added in the 1980s, while Disney DIS, Walmart WMT, and Microsoft MSFT were added in the 1990s.

Why Companies Enter and Exit The S&P Dow Jones Indices, one of the largest index-providers, doesn't have concrete, objective rules for what stocks should be included in the Dow. However, there are general guidelines.

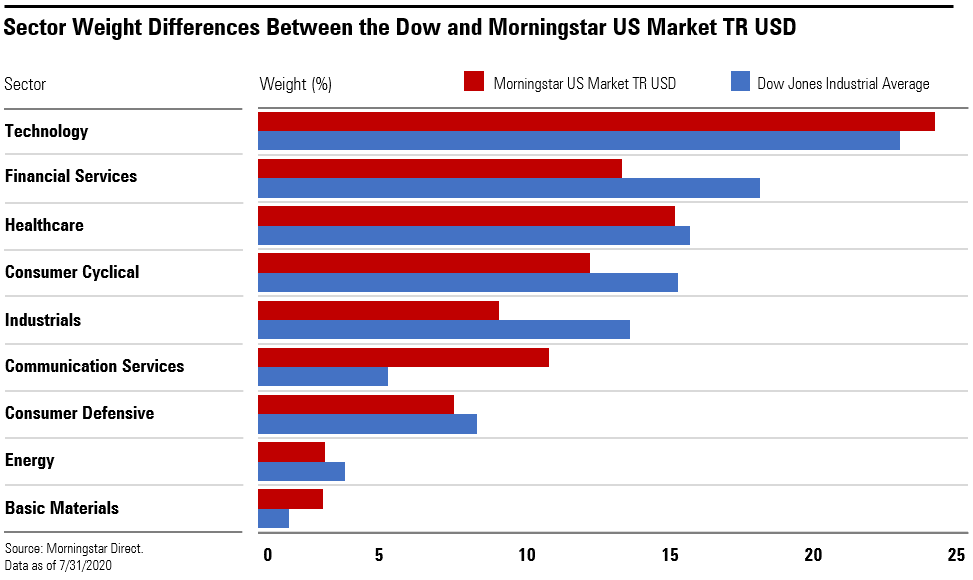

The first “rule” is that members should broadly represent the U.S. economy and stock market. As a result, the index today tries to equally represent sectors in the U.S. economy like technology, healthcare, financial services, consumer, energy, and manufacturing companies. Despite its name, it is no longer an “industrials”-focused index.

The second guideline is that companies should represent recent economic trends. For example, as large tech companies gained influence in the U.S. economy over the past 20 years, many tech stocks received Dow invitations: Intel INTC was added in 1999, Cisco Systems CSCO in 2009, and Apple in 2015.

And that’s about it. It’s difficult to find more trends in why some companies enter and exit--especially when a company is removed and then reinstated. Chevron CVX was in the Dow from 1930-99 and added back in 2008, and it remains. Honeywell was removed in 2008 but added back this year.

Common Concerns With the Dow Because of a few factors, the Dow isn't the best gauge of U.S. stock market performance.

1. It's a price-weighted index. A price-weighted index takes the average of all stock prices. For example, there were only 12 stocks when the Dow first started, so the average was the sum of all prices divided by 12. Because the Dow now has 30 stocks, it's reasonable to think the sum of all prices divided by 30 would give us the average. However, company stock splits, spin-offs, and other corporate actions alter the math behind the calculation. Instead, the sum of all 30 prices is divided by the Dow Divisor, which is calculated by The Wall Street Journal.

Price weighting prioritizes stock price, which is an arbitrary indicator of stock performance, says Karen Wallace, Morningstar director of investor education. "Relative to another firm's share price, it tells you nothing," she notes. A more accurate measure of stock weight is market capitalization (or market cap). This figure takes the stock price and multiplies it by the total number of shares the stock has. Many U.S. stock indexes, like S&P 500 and the Morningstar US Large Cap Index, weight stocks by their market cap rather than their stock price.

2. Its stock-selection process isn't clear-cut. Because Apple's stock split reduced the Dow's technology weight, the S&P Dow Jones Indices decided to add another tech company, Salesforce. However, there are plenty of other tech companies that many say better represent the U.S. economy, like Google GOOGL or Amazon.com AMZN. However, these companies have much higher stock prices than Salesforce and would result in the Dow overweighting in technology. The index needed to fill its technology gap but at the correct price to match the Dow's desired sector weight.

3. It comprises only 30 stocks. The Dow seeks to broadly represent the U.S. economy and stock market--but it's hard to do that with just 30 stocks. The S&P 500 does a better job. It looks at the largest 500 companies by market cap in the U.S. stock market. The Morningstar US Market Index, which targets 97% of all U.S. stocks, includes nearly 1,400 stocks.

What This Means for Investors Although the Dow has strong name recognition, most investors shouldn't pay it much attention. Other market-cap-weighted indexes are better representatives of the U.S. market--and better benchmarks for your equity allocations.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/8b2c64db-28cb-4cb4-8b53-a0d4bc03a925.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IFAOVZCBUJCJHLXW37DPSNOCHM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/JNGGL2QVKFA43PRVR44O6RYGEM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/GQNJPRNPINBIJGIQBSKECS3VNQ.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/8b2c64db-28cb-4cb4-8b53-a0d4bc03a925.jpg)