The New Yorker, October 9, 1995 P. 50

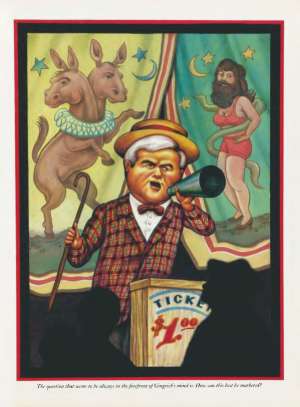

PROFILE of Rep. Newt Gingrich. For roughly thirty-five years, Newt Gingrich has studied political leaders--despots as well as democrats--and has worked hard at refashioning himself so that he might become one. "I'm not a natural leader," he acknowledged when writer asked him about this process, in a recent interview in his office at the Capitol. For the majority of House Republicans, Gingrich is not only a powerful leader but a deeply charismatic one, who inspires them by evoking, time and again, the meaning and majesty of their mission. Tells how he compared himself to Kemal Ataturk, the founder and first President of the Republic of Turkey. Tells about his early history as a politician in Georgia. Tells about his divorce. In 1984, Mother Jones ran what has become the famous story of Newt's visiting Jackie in her hospital room, after he had undergone surgery for cancer, and pulling out his yellow pad to go over their divorce settlement. Tells how he cultivated the military and bumped Rep. Guy Molinari from an investigative committee after Molinari offended one of Gingrich's corporate constituents. Describes his campaign to unseat House Speaker Jim Wright. Tells about GOPAC, Pete du Font's leadership PAC, which Gingrich made videotapes for and headed. In 1989, Gingrich became the Republican Whip. For someone who has risen to power in large part by launching prosecutorial attacks on others' ethics, Gingrich has been remarkably willing to exploit those gray areas that call into question his own ethics. Tells about his use of his office to get his second wife a job; and about his $4.5 million book deal. "Newt Gingrich is the first conservative I have ever known who knows how to use power," Paul Weyrich said. If Gingrich's fondest hopes are realized, and he ultimately achieves the Presidency, perhaps in the year 2000, perhaps with a Republican-dominated Congress, just what he would have in store for this country is unknown. The biggest hurdle confronting Gingrich is the one he has until now managed never to take: appealing to the broad mass of the American people. It seems extremely unlikely that in reasonably normal times in this country Gingrich could prevail in a national election. But the worse the crisis, the better for Gingrich; the greater the insecurity and despair, the more seductive his veiled scapegoating, his absolutism, and his messianism would become. Gingrich plays by his own rules. By being engaging and colorful and dynamic--by staging bravura performances--he usually gets away with it on matters large and small. Gingrich has an enormous advantage in the political arena. He is free to say and do what he pleases, affording himself the kind of freewheeling latitude others can only fantasize about. That license goes unchecked, in large part, because what he does defies our most fundamental assumptions: one simply does not expect to find so consummate a con artist serving as Speaker of the House.