In 1925 the Mexican philosopher, writer, and former education minister José Vasconcelos published an essay that was as consequential as it was absurd. “La raza cósmica” (“The Cosmic Race”) was an esoteric meditation on the future of civilization, which helped shape the way race is viewed in Latin America to this day. Its premise is that history is a lengthy struggle between Latin and Anglo-Saxon cultures; this conflict continued in the New World with Spain and England’s enterprises there. In the future, he argued, this struggle would be resolved by the arrival of the so-called fifth race, which would emerge from the Americas as a hybrid of all other races—Black, white, Indigenous, and Asian.

Sounds good? Well, this is where Vasconcelos goes off the rails. The fifth race would settle in the Amazon, where they would build a utopia called Universópolis, from which they would deploy their armies to “educate peoples for their induction into knowledge.” This “final” race, “a race made with the treasures of all those before it,” would be singularly beautiful, he wrote, because “the very ugly will not procreate.”

“La raza cósmica” might seem like a detour into the Mexican bizarre. And, in many ways, it is. One of Vasconcelos’s many cockamamie theories is that Indigenous peoples of the Americas are the long-lost descendants of the inhabitants of Atlantis. But the essay’s broader idea proved influential, putting forward a pan–Latin American identity—“Latinidad”—based on the figure of the mestizo, a person of mixed race. (In Latin America mestizo mostly describes people who are of European and Indigenous descent.)

Vasconcelos was hardly alone in promoting the idea of mestizaje. He was part of a wave of nineteenth- and twentieth-century artists, intellectuals, and political leaders across Latin America who in the hybrid figure of the mestizo found a unifying narrative for a fractious continent. Vasconcelos, however, was particularly well positioned to popularize the idea: as an educator, politician, and public intellectual, he shaped pedagogies and built libraries at a time when Mexican culture was reverberating throughout Latin America in the aftermath of the revolution (1910–1920). He also commissioned Diego Rivera to paint a series of murals depicting aspects of Mexican culture and history at the National Palace and the headquarters of the Ministry of Public Education in Mexico City. These show the violent subjugation of Indigenous people by the Spanish; they also present the mixed-race society that emerged as a result. One panel at the National Palace shows conquistador Hernán Cortés beside the Indigenous woman Malinche, who carries their mixed-race child on her back. Rivera was far more realistic than Vasconcelos in revealing the violence that was the source of so much mestizaje, but his murals—lasting artistic achievements—nonetheless promoted the idea of an all-encompassing mestizo identity.

Vasconcelos’s reach even extended north to the United States. In the 1960s “La raza cósmica” was seized upon by Chicano artists and activists who were intrigued by the politics of the Mexican Revolution and Vasconcelos’s notion of a collective identity. In this setting, an embrace of mestizaje became a statement of affirmation, and “la raza,” a phrase used colloquially among Mexican-Americans when referring to themselves, was popularized as a rallying cry, appearing in the names of newspapers and art and activist organizations, its central concept of hybrid and in-between states represented in countless murals, paintings, and prints.

This included imagery that, like Rivera’s, tackled colonization and all that followed. A 1974 print by the Texas-born artist Amado M. Peña, for example, who is of Mexican and Yaqui ancestry, shows three heads fusing into one, under which is written “MESTIZO.” Others engaged these concepts more indirectly. In his fantastical paintings, the late Los Angeles artist Gilbert “Magu” Luján created imaginary landscapes that feature Western and Indigenous architectural forms, as well as nods to Southern Californian car culture. “Viva La Raza” (Long Live the People), an expression popularized by the Chicano civil rights movement and emblazoned in many murals, became a shorthand for empowerment. When the Mexican-American performer Kid Frost rapped “This is for La Raza” on MTV in the early 1990s, before bouncing lowriders and cityscapes with Chicano murals, he owed a sliver of intellectual debt to Vasconcelos.

To this day, Latinidad—the spacious container of pan–Latin Americanism—remains the dominant way of understanding identity in Latin America and, by extension, Latino identity in the United States. Yet politically, culturally, and artistically, the term is losing its usefulness, fractured by all that it holds and all that it has erased.

In the 2020 US presidential election Donald Trump received a higher proportion of the so-called Latino vote than he had in 2016, leading much of the media to (belatedly) realize that Latinos are not a monolithic group and may be affected by some of the same issues of race, class, and economic self-interest that shape the US electorate as a whole. “If we want to understand how Latinos vote,” wrote the New York Times opinion editor Isvett Verde last November, “we should start by retiring the word ‘Latino’ entirely.”

Advertisement

Last year’s Black Lives Matter uprisings brought further scrutiny to the ongoing debate about who exactly is included in the meaning of “Latino.” In 2018 #LatinidadIsCancelled became a popular social media hashtag after the Afro-Indigenous artist and writer Alan Pelaez Lopez, who is from Mexico, used it in an Instagram post. Pelaez Lopez made note of the ways this catchall identity favors European culture at the expense of Black and Indigenous representation. To be Latino in the popular imagination is to exhibit some combination of (light) brown skin and speaking Spanish. Pelaez Lopez’s point was revived this summer in the controversy over the casting of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s movie musical In the Heights, which favored fair-skinned Latino leads for a story set in Washington Heights, a historically Afro-Dominican neighborhood. (In response to accusations of colorism, Miranda apologized: “I hear that without sufficient dark-skinned Afro-Latino representation, the work feels extractive of the community we wanted so much to represent with pride and joy. In trying to paint a mosaic of this community, we fell short.”)

But obscuring Blackness and Indigeneity is at the very root of Latinidad, which privileges an identity that, though mixed, is always firmly rooted in the European. Vasconcelos said as much in “La raza cósmica.” He may have rhapsodized about mestizaje, but he by no means viewed the existing races as equal. He celebrated the Christian evangelization of Indigenous people, which he claimed brought them out of “cannibalism into relative civilization” in just “a few centuries.” (And, as Mexico’s secretary of education, he disapproved of teaching Indigenous schoolchildren in their native languages.) He described Asians as “reproducing like mice.” In the utopia he envisioned, Black people would be completely absorbed into the new fifth race—i.e., disappeared through miscegenation. Vasconcelos is clear that his cosmic race is less a true hybrid than a mixture in which a lot of Spanish includes a few dashes of other races.

In truth, in Latin America, identity is not one, but many: Black, white, Indigenous, Asian, mestizo, and various permutations thereof—with ethnicity, language, sexuality, gender, and national identities also critical to determining how individuals see themselves. As in the US, systemic racism has kept those who aren’t fair-skinned or those who don’t acculturate on the margins. The UN Refugee Agency’s human rights reports on Latin America are primers in the disenfranchisement of Black people and the dispossession of Indigenous people from their lands. But you don’t need to read bureaucratic reports to figure that out. Simply tune your television to a Spanish-language channel—you’ll see who is held up as the ideal. Latinidad as a concept may be predicated on mestizaje, but in practice it is bound by whiteness.

All of this makes it a fraught time to organize an exhibition around Latino identity. Which aspects of our tangled histories do you highlight, and which will remain hidden? In its newly reconceived triennial exhibition, El Museo del Barrio in New York City smartly embraces these long-running arguments instead of papering over them with some idealized vision of Latinidad. “Estamos Bien: La Trienal 20/21” finds artists rattling notions of identity rather than trying to uphold them. This begins the moment you walk through the door, with an installation titled Who Designs Your Race?, a participatory work by Collective Magpie, a duo made up of MR Barnadas (who is of Peruvian and Trinidadian origin) and Tae Hwang (who is Korean-American).

The piece takes the idea of a government census and transforms it into an exercise in perception. Barnadas and Hwang surveyed nearly four hundred participants about how they perceive their identity in different situations. (Anyone, not just Latinos, could take the survey.) For example:

I feel Latino/a/x

__Not at all

__Just a little

__Somewhat

__Moderately

__Quite a lot

__All the time

Respondents were then asked to articulate exactly when and where they felt this way. (You can take the survey yourself at theracesurvey.com.)

Collective Magpie created diagrammatic representations of some of the more memorable (and poetic) responses. “I feel Hispanic when clicking forms,” reads one thought bubble. “I feel Cuban when I am homesick,” reads another. “I feel Black when I listen to music.” It is identity as a constantly shifting Cubist perspective, not a fixed point. There are no absolutes, no Universópolis, no colorless fifth race, only identity as a fluid state.

That fluid state informs “Estamos Bien” as a whole. The show, as the accompanying catalog notes, offers a broad approach to “the concept of Latinx,” using a word that is still being defined. While the terms “Latino” and “Latina” still predominate in the United States, “Latinx” has emerged as a way of doing away with the gender binary, as well as any preconceived notions about what is considered Latino. I identify as Latina and often use “Latino/a” in my writing. But I employ “Latinx” when it’s preferred by an individual or an institution, or when I want to convey aspects of identity that are not adequately captured by existing terminology. (And for the record, I am a fair-skinned mestiza of Peruvian and Chilean descent.)

Advertisement

In a conversation published in the catalog, the Dominican-American artist and independent curator Elia Alba, who helped organize the triennial exhibition, describes “Latinx” as not an identity to be worn but “a destination or space where I can connect with all my brothers and sisters of Latin American and Caribbean descent.” It’s a definition I find poignant and expansive. It also perfectly suits the nature of the exhibition, which contains loosely arranged works that tackle notions of identity in many ways. The forty-two artists and collectives represented explore landscape, the body—both human and political—and formal questions of artmaking. (It ain’t a triennial unless the art is commenting on itself.)

A pair of galleries show Latinx artists in dialogue with Western art history, but subverting it too—with color, craft, inexpensive materials, and the ebullient ethos of rasquachismo. The term comes from the word rascuache, Mexican and Central American slang that means something of little value. Rasquachismo refers not to a particular style or aesthetic but to a point of view—that of the underdog. It’s “an attitude rooted in resourcefulness and adaptability,” writes the cultural critic Tomás Ybarra-Frausto in his 1989 essay on the subject. It puts a high value on “making do”—recycling what might otherwise get thrown away. And it parallels the ways African-American assemblage artists have breathed new life into discarded materials. At “Estamos Bien,” rasquachismo is in the room.

The Mexican-American artist Yvette Mayorga embraces excess and Latin American rococo in electric, candy-colored works that borrow from the flamboyant cakes that are a staple of Mexican bakeries (see illustration on the cover of this issue). She paints not just with brushes but with the piping bags used to ice cakes. In electric pinks, gleaming whites, and sparkling gold, she renders contemporary still lifes inspired by seventeenth-century Dutch vanitas paintings, in which a skull is artfully arranged on a table with flowers and books. Her versions, however, contain lacy images of laptops and cell phones, brilliant jewels and acrylic nails, as well as an embedded text referring to US Immigration and Customs Enforcement that reads “FICE,” for “fuck ICE.”

Mayorga’s work, to some extent, borrows from the techniques of the California artist Wayne Thiebaud, who in the 1960s began to paint cakes that exude an uncanny degree of cake-ness because they were painted in the same way a cake might be frosted: with broad strokes and rich texture. Mayorga takes the techniques of a highly ornate style of cake decoration and uses them to capture Latinx states in the US, including anxieties around deportation.

Far sparer is a pair of works by the Dominican-American artist Yanira Collado, who engages the visual language of minimalism in her work. Out of jabón de cuaba, a soap often found in Dominican homes, she has crafted a pair of geometric sculptures. One is a rectangular prism, the other a flat, triangular piece that rests on the floor like a two-dimensional pyramid. The triangle is a remarkable work. Collado has dexterously united dozens of smaller pieces of soap triangles together to create a pattern that is reminiscent of quilt-making. Household soap, a product that invokes women’s labor, nods to a form of women’s craft. Quilting is an art form, moreover, that is produced with needle and thread, tools that are “rich with underdog cultural associations,” as the art historian Susan Tallman recently wrote in these pages.*

Jabón de cuaba is perhaps best known under the brand name Hispano, the Spanish word for “Hispanic.” “Hispanic” means, literally, related to Spain; it was the term used by the Nixon administration in the 1970 census, the first that counted Latinos as a standalone group in the United States. The word carries layers of association, and seeing a soap named “Hispano” in a US exhibition brings to mind the conflation of Latinos with domestic labor.

Collado’s installation evokes not only work but magic and enchantment. Cuaba soap is used in the Dominican Republic for spiritual cleanses; if someone puts a hex on you, you can use the soap in a counterspell. In a conversation published in Bomb magazine in 2019, Collado said that she sees elements of her work as “a protective offering,” the veiled symbols within them “linked to a group of people who may have experienced a loss or uprooting.”

Migration, the city, land, and the arbitrary nature of borders: these all emerge as central to the space called Latinx.

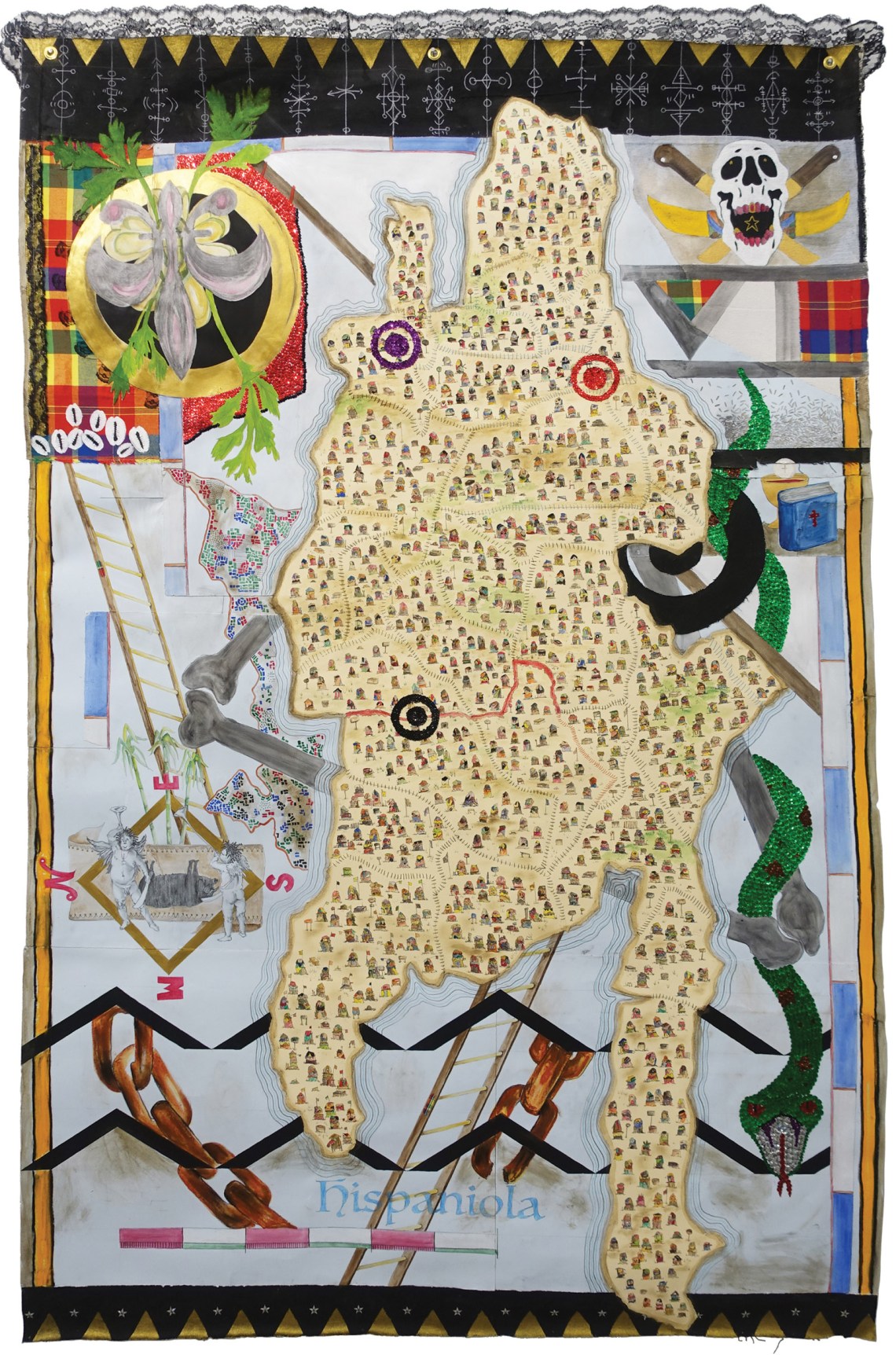

Nyugen E. Smith, an artist with roots in Haiti and Trinidad and Tobago, creates works that explore the emotional connections people can form with a place and the subjective ways those places are mapped. On view in “Estamos Bien” is Smith’s 2018 painting Bundlehouse Borderlines No. 6 (_emembe_), which features an image of Hispaniola (Little Spain), the island shared by Haiti and the Dominican Republic (see illustration on page 20). Smith creates his map paintings using soil from the location he is depicting—a gesture of yearning, as well as a way of literally embedding a place into a map. That’s about as literal as it gets, because the artist also includes invented cartographic symbols—say, a pair of putti playing trumpets before an upside-down pig—and he rotates the island ninety degrees, rendering the geography unrecognizable. Haiti and the Dominican Republic, generally presented side-by-side, are now seen with the Dominican Republic on top. It’s a telling position. The two countries have a famously contentious relationship, with the Dominican Republic regularly enacting racist, anti-Haitian policies and Haitians serving as underpaid, undocumented laborers in Dominican cane fields.

But the real revelation is Smith’s work in sculpture. His “bundlehouses”—two of which are on view—are architectonic structures crafted from scraps of cardboard, fabric, and other urban flotsam, which are then perched on wooden legs. Inspired by the improvised architecture of shelters in refugee camps, Smith has been producing these at various scales since 2005. Some are large enough for a person to enter, while others, like the ones at El Museo del Barrio, fit comfortably on a pedestal. Tiny versions of these also materialize as patterns in his map paintings. Influenced by nkisi, protective sculptures from Central Africa, they are architecture infused with an animist spirit—buildings that protect but that also look like they could get up and saunter away. The bundlehouses conjure migration (forced and otherwise) as well as exile, evacuation, and homelessness. If Latinx is a space, it is one that can be carried and deposited wherever you go.

Other artists address geography on an urban scale. The Los Angeles artist Patrick Martinez creates works that are less paintings than they are architectonic reimaginations of the city he inhabits. The artist, who is of Indigenous, Mexican, and Filipino descent, creates large-scale, multimedia paintings that evoke the façades found in Latino working-class neighborhoods at a time of rampant gentrification in the city. These are works—made with ceramic tiles, window grates, and LED lights flashing advertisements for face masks—that carry the weight of Los Angeles and conjure the frantic dialogues between century-old Spanish revival architecture, commercial signage, murals, and graffiti.

The Salvadoran-American artist Eddie Rodolfo Aparicio, who also lives in LA, takes rubber casts of the ficus trees that shade many of the city’s sun-blasted streets—among them, Central American neighborhoods like Pico-Union and Westlake. Trees are already repositories of environmental memory; Aparicio memorializes them further. After taking a cast, he unfurls the rubber and presents it like a tapestry—hung on a wall or suspended from the ceiling. Their material nods to the work of Robert Overby (another Angeleno), who took latex casts of buildings and presented them in galleries like architectural ghosts. Aparicio, however, uses his rubber casts as canvases for paint, textiles, and objects he finds in the street. A particularly majestic example is El Ruido del Bosque Sin Hojas/The Sound of the Forest Without Leaves (2020), which is fringed with broken bottles he collected from friends and family. Approach the piece in the museum and you can practically feel the city crunch beneath your feet.

His works pay tribute to Los Angeles; they also refer to the ravages of US foreign policy in his parents’ native El Salvador. In the early 1980s, during the civil war, the US-trained military used incendiary weapons to burn down forests that sheltered insurgents. Those trees are gone, but Aparicio will not let us forget.

It’s in the work relating to the body that you feel the beating heart of “Estamos Bien,” prodding the boundaries of sexual identity and gender roles, using self-representation to shatter bland notions of Latinidad.

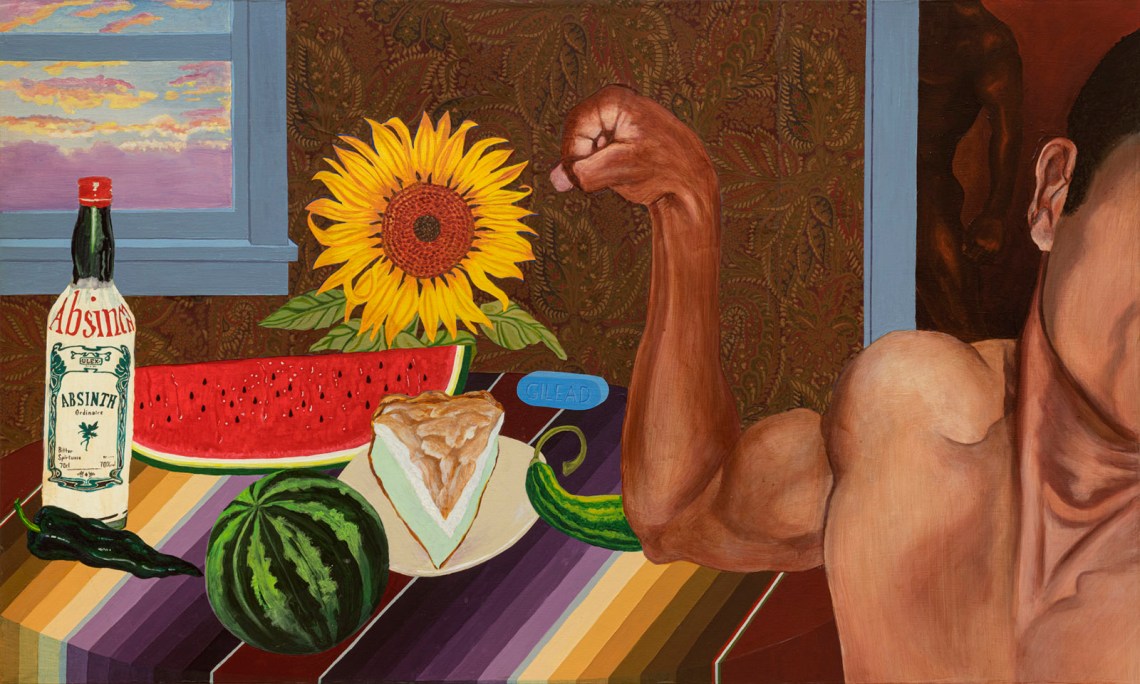

The show includes three deeply affecting canvases by the Los Angeles-based artist Joey Terrill, who is Chicano. Since 1997, Terrill has worked on a series of sumptuous still lifes that feature achingly ripe fruits alongside sexually suggestive commercial products and name-brand HIV medications. In paintings such as Black Jack 8 and A Bigger Piece, both from 2008, we see hard-bodied men presenting themselves for inspection amid images of a fruit cocktail and breakfast cereal. Multimedia elements—such as fragments of kitschy wallpaper and old candy wrappers—add a touch of rasquachismo. It’s a mordant intersection of sex, death, and consumerism at the turn of the twenty-first century—a memento mori that also functions as memento vivire. The works depict Terrill’s own journey: the artist has lived with HIV for four decades.

Far more somber is the record of the performance piece staged by Cuban-born artist Carlos Martiel. Martiel is known for difficult, endurance-based pieces that comment on the ways Black people have been marginalized and dehumanized by colonialism. In one 2013 piece at the Nitsch Museum in Naples, Italy, he stood nude in a gallery, his bare skin pierced by dozens of threads that connected to points on two walls—one that stood before him and the other behind. I saw a video of that work at an exhibition of Caribbean art at the Museum of Latin American Art in Los Angeles in 2017 and was both terrified and riveted by it—a man rendered unable to move by the threads that tugged at him in opposing directions.

At El Museo, Martiel dipped himself in the blood of people who have been, in the artist’s words, “discriminated against, oppressed, and marginalized by Eurocentric…discourse”—Black, Native, Indigenous, queer, and transgender. He then proceeded to stand on a sparkling white plinth inside the museum for several hours. El Museo was closed because of the pandemic, so the performance took place in an empty gallery; the piece, titled Monument I, now exists in video form. But it’s the plinth, which is also on view, that is truly poetic: absent Martiel’s body, it bears only the bloody imprint of his feet, and speaks to current debates about the nature of monuments and our legacies of slavery, genocide, and violence.

“Estamos Bien” was organized by Elia Alba in collaboration with Susanna V. Temkin, a curator at El Museo, and Rodrigo Moura, its chief curator. The show represents a reimagination of the museum’s regular artist survey, “The (S) Files,” which was held seven times between 1999 and 2013. That show focused primarily on emerging artists in the greater New York region. Now it has been reborn as an expansive triennial that includes Latinx artists, both emerging and established, from across the United States and Puerto Rico.

“Estamos Bien” was originally scheduled to go on view in 2020 but Covid-19 pushed its opening to the spring of 2021, during a pandemic that is not yet over, in the aftermath of a global uprising in support of Black lives, as well as an election that resulted in white supremacist violence. In a show that includes Puerto Rican artists—both from the island and in diaspora—there is also the specter of another catastrophe: Hurricane Maria, the 2017 storm that left thousands dead and laid bare the ways US rule has strangled the island’s autonomy and, by extension, its ability to recover from disaster.

The title of the show, in fact, is indirectly inspired by the hurricane. On view in the galleries is one of Candida Alvarez’s “air paintings”—double-sided works on canvas that are suspended like laundered sheets from a free-standing structure in the center of a room. Alvarez is a Brooklyn-born painter of Puerto Rican origin, known for creating works that feature abstracted figures and forms in fecund riots of color. For the triennial, she presents a painting that could be a bird’s-eye view of Puerto Rico in the aftermath of Maria (or Louisiana in the wake of Ida): swaths of watery blues and muddy browns surround a green patch on which is written the hopeful phrase estoy bien (I am good).

The words, which are also the title of the piece, were Alvarez’s response to questions about how she felt after the hurricane (an event that coincided with the death of her father). The phrase—and the painting—suggest a stubborn resilience: I am good. I am here. I am alive. The phrase “estamos bien” expands Alvarez’s title to the plural “we”—and winks at a song of the same name by Puerto Rican reggaetonero Bad Bunny. It is, the curators write in the catalog, a “rallying cry.” And a bit of hope in turbulent times.

This Issue

October 21, 2021

The Storyteller

Are the Kids All Right?

-

*

“Knowing How,” The New York Review, August 19, 2021. ↩