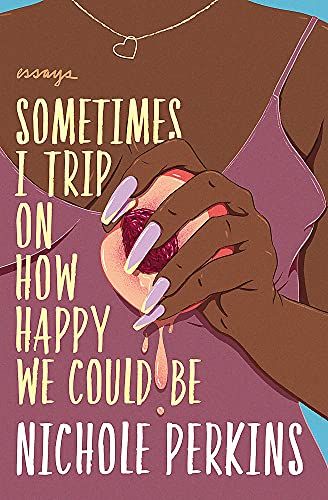

Excerpted from the book SOMETIMES I TRIP ON HOW HAPPY WE COULD BE by Nichole Perkins. Copyright © 2021 by Nichole Perkins. Reprinted with permission of Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.

My parents liked to send messages to each other via song. The entire song didn’t necessarily have to apply to whatever situation was going on in their marriage. The chorus was the most important part, even just a line or two. My father would come home after being God knows where when he should’ve been at work, and my mother would cue up “It’s Over Now” by Luther Vandross. It was a song about someone suspicious that his lover was cheating. The chorus went: “You did me bad / It’s over now / You treated me so bad / It’s over now . . . ” I don’t know if my mother really thought he was cheating. I just think she wanted to let him know she knew he had not been doing what he should have, and she was over it. Depending on my father’s mood, he’d give as good as he got, usually with Rick James’s “Cold Blooded.” The song was about how sexy Rick’s lover was and how he hoped she’d return his attention, but my father focused on that repeated chorus of “She’s cold . . . blooded.” He wanted to call her cold because she couldn’t tolerate the way he’d neglect his responsibilities. I got to hear a lot of good music because of my parents’ coded fighting.

In 1986, Janet Jackson’s album Control began to take the world by storm, and the eponymous single rocked my home. My mother’s passive-aggressive game skyrocketed. Janet was twenty and ready to establish herself as more than Michael’s little sister. She wanted to show the world her independence, talent, and maturity. My mother was thirty-two. She’d never lived alone. A teenage mother, she went from her childhood home, following the rules of the grandmother who raised her, into what would become an abusive marriage, and she’d never had a chance to establish her own identity. Although Janet was much younger with a vastly different childhood, I think my mother connected to Janet’s journey of finding and assert- ing herself. And Mama was losing patience with my father, his addictions, his abuse, his irresponsibility. She had been working as a nurse at the same clinic since before I was born. In every corner of her life, she was taking care of someone— her patients, her children, and her trifling-ass husband. Mama was tired and ready to gain control over her life.

Enter Janet Jackson’s third album and its lead single.

If my mother started playing “Control,” it was for a few reasons:

- It annoyed my father.

- She was giving herself a musical pep talk.

- She was letting my father know that for all his abusive bluster, she was the decision maker in the household.

- The album was banging, and no one could deny that.

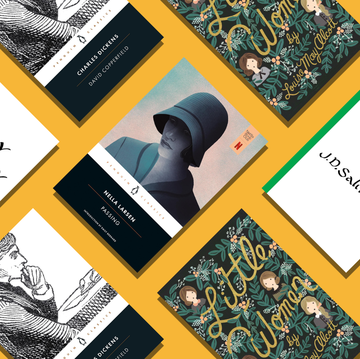

When Control came out, MTV and BET played music videos around the clock. Janet released a video with every single. She danced her heart out, creating choreography that’s been passed all the way down to the TikTok generation. In most of the videos from this album, Janet wears all-black attire. I was eight years old at the time and didn’t think much about it until I overheard someone say that black was slimming and that Janet was trying to hide her chubbiness.

I don’t know when my body image issues began, but they feel as part of me as my moles. When I was a little girl, I was so skinny and small people always thought I was younger than I was. As a tween, my worst fear was that someone would say I looked like a boy. All those fast-developing friends magnified my lack of curves. I’d stand in front of the mirror, wondering when my hips and breasts would arrive. My mother laughed at me and told me I wouldn’t want them when I got them, but I was impatient and envious.

A late bloomer, I envied Janet’s all-black uniform and how it was supposed to hide her shape from the world. I wanted that. I needed to hide. I didn’t have the shape a Black girl was supposed to have, so I wanted to make myself invisible.

Wearing fashionable, pretty clothes with bright colors and interesting patterns got compliments, but it also had people looking at your body. I didn’t want to bring any more attention to my lack of breasts or whatever else I thought was the marker of moving into womanhood. So when junior high hit, and my parents finally divorced, about three years after Control came out, I started adding more and more black clothing to my wardrobe.

Mama hated it. She loved to stand out—with animal prints and colorful earrings. She wore slips with denim skirts. She dressed in a way that let everyone know she was both woman and lady. My sister was her girly girl, but I hated the pinks and flower prints my mom tried to dress me in. I wanted plain T-shirts and black jeans and black sweatshirts and black dresses. All I could think about was “Black is slimming,” so if I had nothing to begin with, maybe in all black I could totally disappear.

As my parents’ relationship withered, Janet’s career as an independent woman and artist grew. Her waistline shrank. Her clothes became more colorful and covered less flesh. My body changed, too. I got hips and a little bit of boobs and a healthy portion of ass, but I still wanted to hide. The ass brought too much attention. I understood why. It was the perfect shape to welcome faces. (It still is; there’s just a bit more of it now.) Guys I dated wanted me to show off—but not too much.

I remember my college boyfriend and me leaving a friend’s house where ten or so dudes were “making music” (read: smoking weed and playing video games) and he scanned the room to make sure no one was watching my ass in the tank dress I was wearing. I can’t front. It had a really nice jiggle back then.

The thing is, I gained the college freshman 15 and then the sophomore 10 and the junior 10. My curves filled out, and I had the perfect southern-woman silhouette . . . and still I wanted to hide.

Yes, I’d been waiting for my Coke-bottle shape since I was eight years old, but I was supposed to have a flat belly and overflowing breasts, too. Instead, the curves came with a little belly that I had to suck in and breasts that were still small (but perky) as hell.

My mother would look at me and my new filled-out shape and become emotional. “You’re such a woman now,” she’d say before commenting on my big legs. Then she’d launch into a series of memories about how little I used to be.

I’d been getting harassed on the street since I was seven years old, so I learned very early on that men will say anything to see how far they can go. That a compliment becomes a threat as soon as you ignore a man. Now, men watched me with even more attention.

Everyone had such different reactions to my changing, late-blooming body, that I kept pulling out my Janet Jackson uniform, kept trying to disappear again into the mystery of all black.

When I was twenty-five, I finally fell in love with my body. I was working out semiregularly. I was exploring casual sex and not worrying about whether men found me marry-able. I loved the power I felt in my body, and then it betrayed me. My spleen spontaneously ruptured, and I had to have emergency surgeries that left me with IBS (irritable bowel syndrome). The PCOS (polycystic ovary syndrome) that had gone undiagnosed since my teenage years began causing me problems, like weight gain, increasingly irregular periods, and other digestive issues. The significant scar from my surgeries sliced my torso in half, from just under my breasts to the top of my pubic area. It moved through my belly button, leaving it crooked and no longer a place for a lover’s tongue. Instead, it left me self-conscious about my body and my wardrobe again. I could no longer wear the crop tops that highlighted my small waist. I had to be careful about bodycon dresses so they wouldn’t show the puffiness of my scar or how one side of my belly had healed weirdly and now sticks out farther than the other in a way that sucking in cannot hide.

Whatever color my wardrobe had gained in the brief time I loved my body was pushed to the side to make room for more black.

Black is slimming. Make me disappear. Black is slimming. Make me disappear.

If you can’t see me, you can’t see all the ways I’m not perfect.

I’m older now and more resigned to accept that whatever shape my body is, that’s just its shape. I didn’t want to spend so much of my time stressing over my body. I tried for so long to be invisible, but I’m here. It feels like my life is finally starting, and I want my life to be bright and colorful. I still wear a lot of black, but I love reds, corals, yellows, blues, and purples.

During my midthirties, I compromised with myself and began wearing gray, accentuating it with bright colors. Shortly after my forties began, I joined a clothes styling service at a department store, and every two to three months, a professional stylist would suggest outfits for me. I asked him to give me colors and patterns; otherwise, I’d fall back on old habits. I don’t know that I’ll ever love my body again, but I’m fine with it. My body is a hormonal, shapeless mess, but it’s keeping me alive (and this pussy still yanks, so . . . I’m good).

Janet Jackson’s Control helped empower my mother to eventually break free from a disastrous marriage. Someone’s gossipy throwaway comment about Janet’s weight and shape sent me on a thirty-year mission of hide-and-seek with my body. That’s not Janet’s fault. I latched on to this comment to gain control over how my body was viewed, but it never really worked. Everyone saw what they wanted to see, even myself.