Rosehill Cemetery in Linden, New Jersey, is awash in small-town trappings: tree-lined roads, rolling lawns, and street signs at every corner. On this Wednesday midsummer morning, the familiar routine of loss plays out across the acres. A yellow taxi waits at the end of a row of graves for someone paying their respects. Men and women clad in church clothes line up their cars along the curb and make their way to a gravesite. A backhoe digs out some earth, another spot for another resident.

This is the textbook way we treat our dead. Someone dies, they’re buried, a headstone marks their place out among the rows in the borough of the departed. But today I’m bound for a different part of the cemetery, one fewer people see.

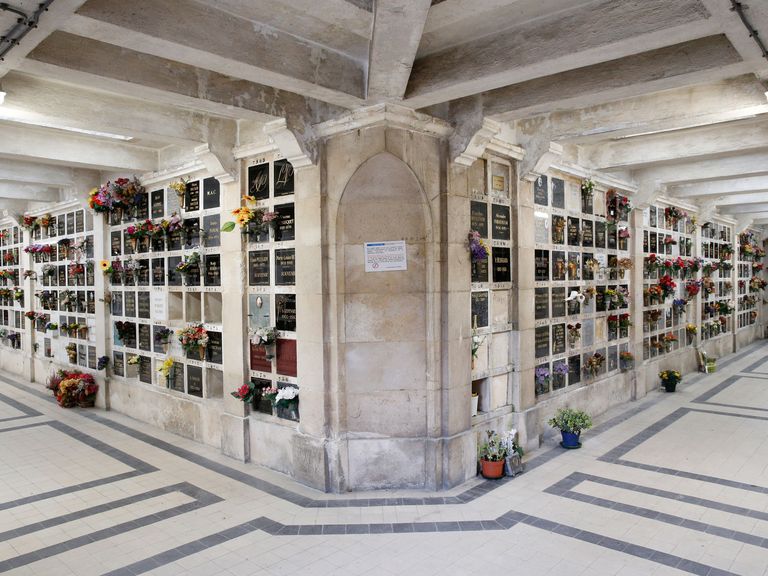

This place is called the columbarium, and at first, the very existence of this vast chamber full of urns can come as a surprise. In the movie version of life and death, a cremated person’s remains sit up on the shelf at home, or friends scatter the ashes over a sacred locale. In the real world, many cremated people stay in the cemetery, just like their buried counterparts.

We are seeing a fundamental shift in how we approach death and what comes after. Compared with just a few decades ago, vastly more Americans are forgoing the old-fashioned burial and turning to cremation. This is what brought me to Rosehill, and now my tour with Jim Koslovski, president of the Rosehill and Rosedale Cemetery, is about to reveal how cemeteries are dealing with America’s after-death revolution.

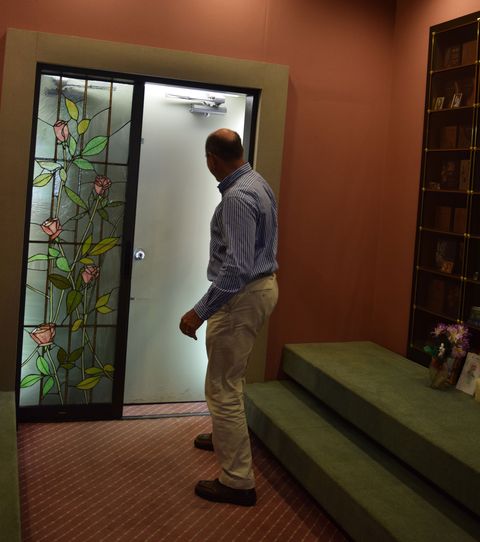

As I follow him deeper inside the columbarium, we come to a set of stained-glass doors. Koslovski slides them open to reveal a hidden set of spy-movie doors made of metal. They are solid for a reason: Behind them lies the crematorium itself.

Socially Acceptable

Back in 1980, less than 10 percent of Americans were cremated. That figure now stands at about 53 percent, according to the National Cremation Association of North America. Changing cultural and religious standards are at play here, but no event accelerated the change more than the Great Recession.

“We saw an increase in the cremation rate when there was the economic downturn in 2008 and people were losing their jobs,” Koslovski says. “Cremation is a less expensive alternative to traditional in-ground burial.”

Rosehill charges just $190 to cremate a body, although the funeral home charges extra for the urn, flowers, and service. A grave, by contrast, can cost $2,500, plus an additional $1,900 to open the ground with a backhoe.

Rosehill, located about a half-hour from Manhattan, now cremates about 30 bodies a day using six cremation units, and has been expanding its facility to meet the growing demand.

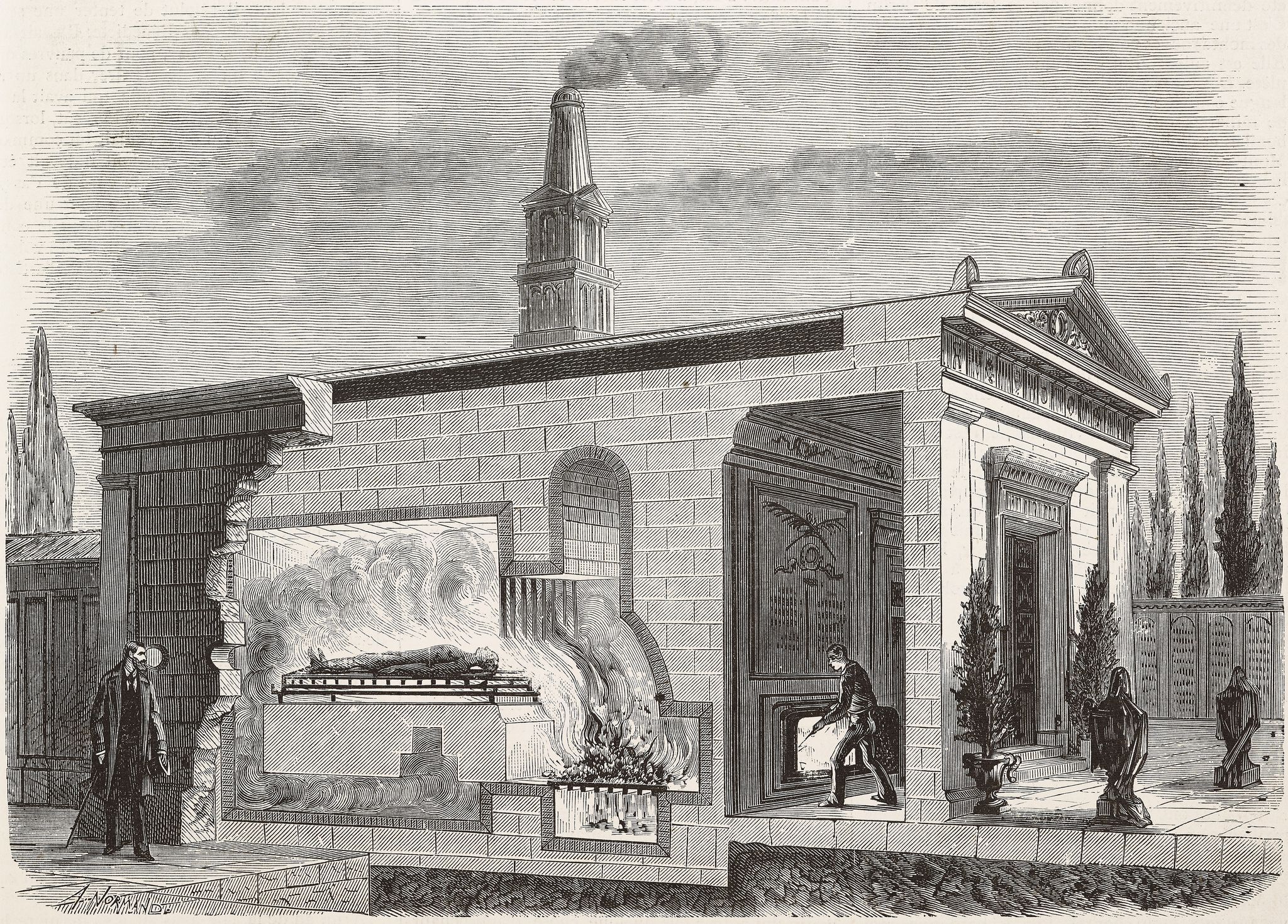

Of course, burning the dead isn’t a new concept. Cremation began in the Stone Age, and it was common in ancient Greece and Rome. In certain religions such as Hinduism and Jainism, cremation was preferred.

The rise of Christianity put the brakes on the practice in the West. By 400 A.D., around the time that the Emperor Constantine Christianized the Roman Empire, Rome had outlawed cremation as a pagan practice. The theological reason for the ban was related to the resurrection—it was good to keep the body whole and in one place. Jewish law also banned the practice. By the 5th century, cremation had all but disappeared from Europe.

The practice saw a resurgence in Europe in the 1870s, mostly in an effort to curb the spread of disease. The first modern crematory was built in the U.S. in 1876. By 1900, there were 20. The practice got another boost in 1963, when the Catholic Church reversed its opinion on cremation during the Vatican II reforms and said cremation was permitted.

Today, there are more than 3,000 crematories around the United States, and the cremation resurgence isn’t just about cost. There are fewer religious prohibitions, and consumers are seeking simpler, less ritualized funerals.

Acceptance varies by state and ethnicity, according to a report by the National Funeral Directors Association. While the practice is not as popular in the Bible Belt and among certain cultural groups, including Catholics, Jews, and African-Americans, in places like California, Oregon, and southern Florida, 60 to 80 percent of the dead are now cremated.

And there’s one more force pushing cremation as an alternative: Cemeteries are running out of space, Koslovski says. He estimates Rosehill has only 15 years before it’s out of available ground.

How Cremation Works

Koslovski and I pass through the double doors. As we stand on the floor of the crematorium, a bell rings out. It indicates that there’s a hearse backing up to the door.

The bodies arrive in caskets occasionally made of wood or metal, but more commonly cardboard, and are kept in these containers during the entire stay. Human remains must be enclosed in caskets for ethical and health reasons, such as protecting the cremation technician from infectious diseases, but also for the safest handling of the remains prior to cremation.

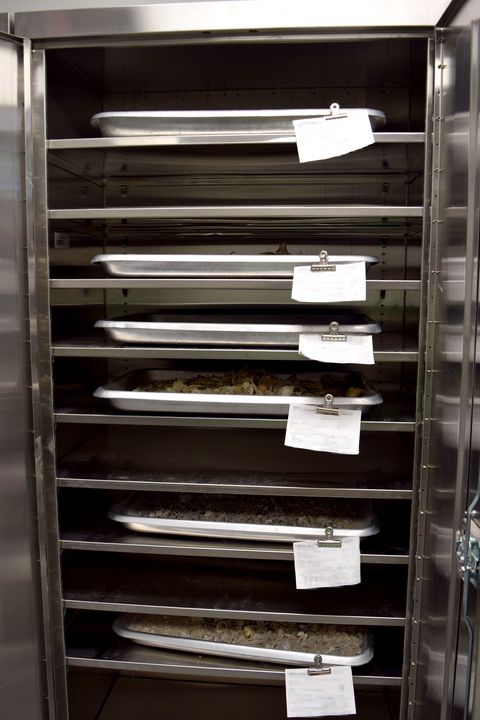

The caskets go into the crematorium’s refrigerated storage area, which is lined with shelves of them. One casket has a label on it from Delta Airlines that says “Human Remains,” and under it, “Delta Cares.” At Rosehill, bodies typically remain a day in the cooler. Koslovski says that Rosehill endeavors to perform all cremations and return remains to the family within 24 hours. And most states require a 24-hour waiting period between when someone dies and when cremation can occur. When something is so final, you want to take a pause.

Six large cremation units occupy the floor, each covered in aluminum diamond-plate like you might see on a fire truck or a high-end toolbox. It’s called a cremation unit, by the way, not an “oven.” There are certain words you’re not supposed to say in a crematorium. “With ovens, you think of Auschwitz,” says Brian Gamage, director of marketing at U.S. Cremation Equipment in Altamonte Springs, Florida.

When a body is ready to be cremated, the casket is removed from refrigerated storage and placed on a hydraulic lift table that looks like a gurney, then wheeled over to one of the machines. An error would be catastrophic and unforgivable, so Rosehill uses two forms of ID to make sure the family gets back the right remains. A copy of the receipt is attached to the outside of the cremation unit, and a metal ID tag accompanies the deceased inside the unit.

While the door can open about 30 to 36 inches wide, most operators open it only a foot or so, enough to accommodate the width of the body. Any more than that will let out too much heat, exposing the operator and the room to fiery temperatures. Rollers on the table slide the casket in.

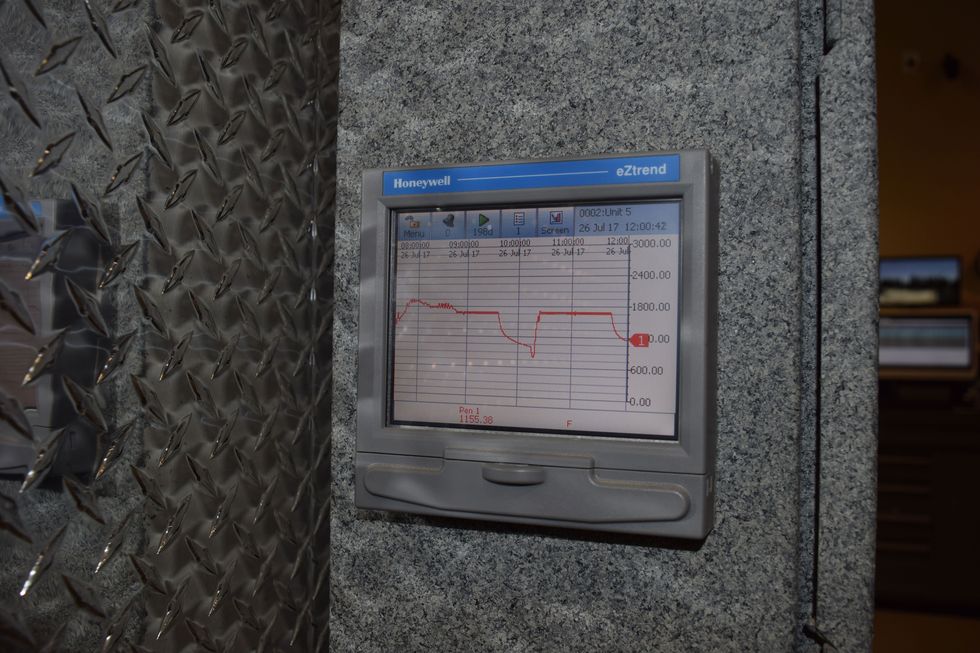

A cremation unit has two chambers: the primary chamber, where the body goes, and the secondary or “after” chamber, which consumes the gases generated by the cremation process. The typical primary chamber has brick-lined walls, and a floor and roof made of high heat refractory concrete. A burner in the roof heats the chamber to about 1,200 degrees Fahrenheit.

The resulting gases and particulates travel into the after-chamber, a 30-foot maze designed to retain the gases for at least one second. The after-chamber subjects the gases to a temperature of 1,700 degrees Fahrenheit to make sure the particles and odor are negligible before everything goes up the stack and out into the atmosphere. Gamage compares the secondary chamber to the catalytic converter on an old car, which neutralizes the emissions of the exhaust system.

“Any solid will turn to gas if heated to the right point. That’s essentially what happens to the body when the tissue is heated to the point where its solids turn to gas and become combustible,” Gamage says. “The key is to design equipment that consumes most of the emissions so that they fall within the state environmental regulations.”

The particulates emitted must be less than 0.1 grains per dry standard cubic foot, according to environmental agencies in most states. Problems arise when the volume of gases (smoke) becomes too great for the after-chamber to process and it overflows. That can happen if the machine isn’t designed properly or if the operator overloads the primary chamber, which can happen for surprising reasons—for example, putting an obese person in the unit at the wrong time of day.

As macabre as it may sound, weight is something crematorium operators must worry about. The machine doesn’t know the difference between a person who weighs 150 pounds and a person who weighs 400. It just does its job. The cremator’s rule of thumb is that 100 pounds of human fat is the equivalent of 17 gallons of kerosene. If you have a body that weighs 400 pounds, at least 200 of them will be fat that burns rapidly. If you put that person into a very hot machine, as a cremation unit tends to be at the end of the day, the chamber may emit smoke and odor out of the stack.

Although some crematories can process a body faster, basic facilities finish a cremation in about an hour and a half. And that varies depending on the person’s weight and the type of casket they’re in. The time-consuming nature limits the number of cremations each unit can handle in a day. During my visit, all of Rosehill’s machines were in various states of operation to keep up with demand. Each needs to get five bodies done in eight hours. Rosehill’s cremation units run six days a week, standing idle only on Sundays.

“For religious reasons?” I ask Koslovski. “No,” he says, “we just need a day off.”

Back to the Earth

We come from the Earth, we return to the Earth. That may be true, but the way we return to the Earth matters on more than an emotional level. It’s an environmental concern. As cremation continues to replace burial as a go-to way of dealing with the dead, the emissions that come along with this process have become a concern—so much so that people are starting to consider some wild-sounding alternatives.

There is now a water-based process called alkaline hydrolysis, which was invented as a way to dispose of animals infected with mad cow disease. It is being marketed as a more environmentally friendly postmortem option for humans because it produces less carbon monoxide and pollution. Alkaline hydrolysis involves placing a body in a chamber that is then filled with water and potassium hydroxide and heated up to 300 degrees Fahrenheit at high pressure. After three hours, the body becomes a green-brown-tinted liquid, and bones are soft enough to be crushed. The bones can be returned to the family, while the liquid can be sent into the sewer system.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, this process has not really taken off. It’s slower. The technology is more expensive: A stainless-steel pressurized unit can cost from $175,000 for a basic unit to $500,000 for a high-end unit, while a cremation unit costs about $110,000. There are legal issues, too, because the process is prohibited unless a state passes legislation specifically allowing for it.

And then there is the “ick” factor: We’re talking about reducing a human body to a soupy mess that goes into the sewer.

Close To Home

When Lisa Tomasello was growing up in a large Italian Catholic family, the death of a relative was just the beginning of a grueling two or three days. Visitors would arrive at the funeral home and sign the guest book, then form a line to get to the casket. People would sit in front of the body of the deceased, kneeling and praying and making the sign of the cross, before kissing them on the hand, face, or lips. “The closer the relation, the closer to the lips,” she says.

The immediate family sat in the front row, receiving visitors in front of the dead body. Tearful outbursts and cries in Italian were commonplace. During the breaks in the wake, the family would go out for dinner and laugh and tell stories before returning to the funeral home for several more hours of crying. And all that was before the funeral, which would start at a funeral home, resume at a church, and culminate at a cemetery before everyone was invited back for lunch.

But once the body was buried and the headstone placed, then what? “My grandparents’ graves haven’t been visited in 30 years,” Tomasello says.

When Tomasello’s own mother passed away, she and her siblings decided to have a small service and to cremate their mother’s body. When her father followed a few years later, they made a toast to him with a shot of Jack Daniels, then had him cremated and divvied up the ashes.

“I have my parents in my bedroom,” she says. “There is no pressure or guilt of having to visit them in a cemetery, and they will stay with me until the end of my time.”

It’s hard to let people go. We want to keep them near, sometimes even anthropomorphizing the urns that hold them as a way of bringing our loved ones back to life. The urn doesn’t contain mom’s ashes; the urn is mom.

What Is Left Behind

There is no easy way to say it: The physical attributes you picture when you envision a loved one—the eyes, the skin, the hair—disappear during the cremation process. “Cremated remains are typically bone fragments and casket ash,” Koslovski says. “Remember, we’re 60 percent water.”

Once the cremation process is complete, the remains are put onto what looks like a silver baking tray. A technician runs a magnet over them to remove ferrous materials that did not combust during the cremation process. These often come from a person’s staples, screws, hinges, and prosthetic joints. The technician will then visually inspect and remove any material the magnet missed—say, the bits of glass left behind because someone wanted their father cremated with a bottle of Scotch. Those pieces are disposed of by the crematory.

The crematorium puts the bones and ash that remain into a pulverizer, not unlike a food processor, to reduce them to a more uniform powder-like consistency. The remains are then put into a container for the family— but not always. Some Asian cultures want to be able to pick through the unpulverized remains to take bone fragments. A skull or hip bone is prized. They don’t want the bone fragments processed at all.

Hindus often want the eldest son to commence the cremation process as a rite of passage, so he’s allowed on the crematorium floor to turn on the machine. Other families just want to observe the process—about a dozen make that request each week. Rosehill allows them to do so, from an observation deck. To Koslovski, it’s about making sure people understand the process, that they’re not afraid or skeptical of cremation because of misinformation or rumor.

I press him on the stories, the urban legends about crematoriums. Is any of it true? Do cremated remains from one person ever wind up getting mixed in with another? He explains that every cremation is performed individually and the cremation unit is swept thoroughly after each one.

However, I remember Barbara Kemmis, the spokesperson for the Cremation Association of North America, telling me that while operators do their best to remove recoverable remains, it’s possible that minute amounts of one person’s cremated remains could inadvertently wind up in someone else’s. Another part of the process that’s perhaps best not to think about.

The Things We Cannot Bury

Cremation, like death, is final. But that doesn’t mean you won’t have second thoughts. Susan Skiles Luke, a marketing consultant in Edwardsville, Illinois, had her mother cremated and buried in a family plot. Now, she wishes it was her mother’s body in the grave.

“When I go there, which isn’t often, I want to feel like her body is underground, not some heavy shoebox of something that looks like cigarette ashes,” she said.

When her older brother, Tom, with whom she was very close, died tragically of a drug overdose 13 months later, skipping the burial in favor of cremation was a godsend. It allowed her to avoid the whole public ordeal of a funeral.

That’s one of the advantages of cremation: You can address your emotional issues with the dead on your own terms. The disadvantage? Now you’re left with the remains, this tangible object impressed with memories. After Luke’s brother passed away, she picked up his ashes on the way home from work, as if it were just another weekday errand. “I wasn’t prepared for how personal it would feel,” she said. “I threw my brother’s ashes in the trunk with a thump and cried all the way home.”

A few years later, when her stepfather passed, she couldn’t bring herself to pick up his ashes, even as the funeral home kept calling. One day, she returned home to find her dad’s ashes sitting on her doorstep. She now has two boxes of remains in storage, though she doesn’t know exactly where. She asked her husband to hide them. “Not the healthiest reaction,” she admits.

Sometimes, instead of burying people in the ground, we bury them among our stuff. We lose them among the emotionally charged paraphernalia of our lives. It is just too hard.

The Missing Markers

In movies, characters are always scattering the ashes of a loved one over the side of a boat or off the top of a mountain. In reality, cremation rarely ends that way. The Cremation Association of North America estimates that 60 to 80 percent of cremated remains go home with people who intend to place them in a cemetery or scatter them at a future date. But scattering is not as popular as people think.

“Based on recent media coverage of people seeking to recover cremated remains lost in fires, floods, and mudslides, I suspect a high percentage of remains are in homes,” Kemmis says.

There are actually laws dictating where ashes can be spread. “You can’t just run down Main Street and throw them in the air or sprinkle them in your neighbor’s driveway,” says Robert Biggins of Magoun-Biggins Funeral Home in Rockland, Massachusetts.

While scattering ashes seems romantic, there’s something to be said about keeping your loved one in one place, and then marking that place with a name so we don’t forget them.

As I leave Rosehill cemetery, I decide to stop by the grave of my friend David, who was dealt a bad set of cards. His mother was an alcoholic. His father had left. He was sent to a city-funded boarding school and managed to graduate with a football scholarship to college, but lasted just one semester. And like something out of a bad movie, he met a girl, was introduced to crack cocaine, lost his job, wound up with HIV, and ultimately developed kidney issues that landed him on dialysis for well over a decade. He was on the kidney donor list and was near the top when he died of heart failure in 2015.

I’d gone to his funeral but hadn’t made it to the cemetery—the one in which I now found myself. I’m surprised to see nothing marking the spot where he’s buried. It’s just a patch of dirt with a number “83” handwritten in concrete. There are big marble headstones on one side of him and on the other side, a pile of plastic flowers, bits of light blue ribbon, and Styrofoam crosses that say “I Love You.”

The lack of fanfare seems unfair. Without a headstone, no one would even know he was under there—or for that matter, that he’d been up here.

Whether it’s a burial or a cremation, the hard part is letting a loved one just float off into obscurity. We need that physical marker, a headstone, a bench, an urn, to show that the person existed, that they once walked this Earth.

I go to my car and find a football trophy my son had dug out of the garbage and thrown on the floor of the back seat. I use a black Sharpie and write on the front of the trophy: “David, April 23, 1954 to April 23, 2015.” I walk over to Grave 83 and place the trophy at the top of the patch of dirt where a headstone might go. I leave a pebble, as people sometimes do, and walk back to my car.

This article was originally published on March 1, 2018. It's been updated after appearing in the November 2019 issue of Popular Mechanics.