Analysis: Mark Duncan analyses what drove the rapid rise of Sinn Féin in the years following the failed Rising of 1916.

Stunning it was, surprising it wasn’t.

While the spectacular performance of Sinn Féin in the 1918 Westminster election transformed the Irish political landscape, it had been widely forecast. Reporting to his Dublin Castle superiors in the immediate aftermath of the declaration of results, the Inspector General of the Royal Irish Constabulary remarked, somewhat resignedly, that that the outcome had been a ‘foregone conclusion’.

But what drove the rapid rise of Sinn Féin, a party founded in the early years of the century and with no electoral track record before a series of by-election successes in 1917?

The answer is not straightforward, but there is little doubt that the growth of the Sinn Fein organisation – it boasted an extensive branch network and a membership of more than 100,000 by the time general election came around – was helped by the blunders of a British government whose mishandling of the Easter Rising in 1916 was compounded by mistakes on Conscription and other issues during the Spring and summer prior to the December 1918 election.

Sinn Féin was likewise helped by its Irish Parliamentary Party opponents, which entered the election weakened by the resignations of many its outgoing MPs and with no home rule parliament to show for its decades of effort at Westminster.

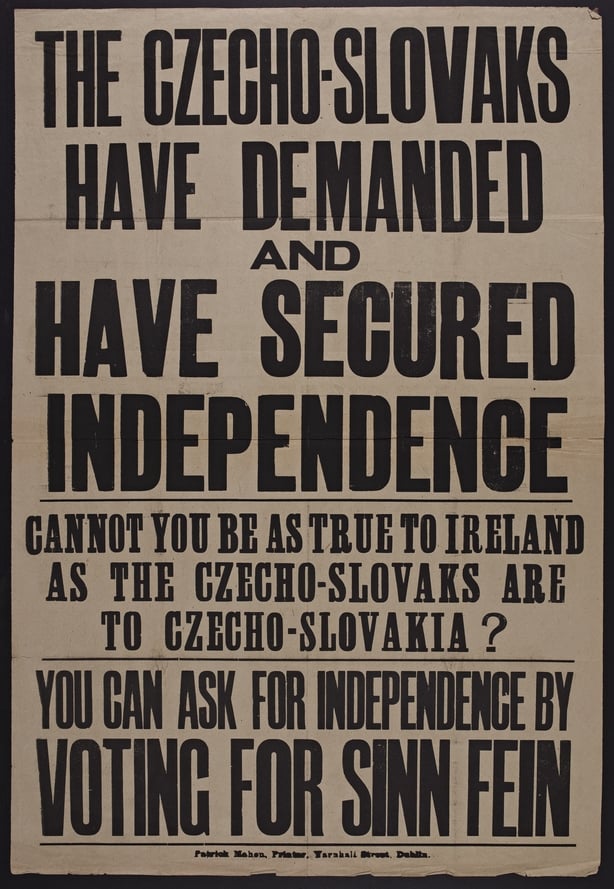

And then, of course, there was the emotional appeal of Sinn Féin’s republican manifesto which seemed fortuitously in step with a post-war international world where empires were crumbling, new nation-states were being born and all the talk was of ‘self-determination’.

For these and others reasons Sinn Féin swept to victory but how Ireland voted in the Westminster election in 1918 had implications that were both profound and far-reaching.

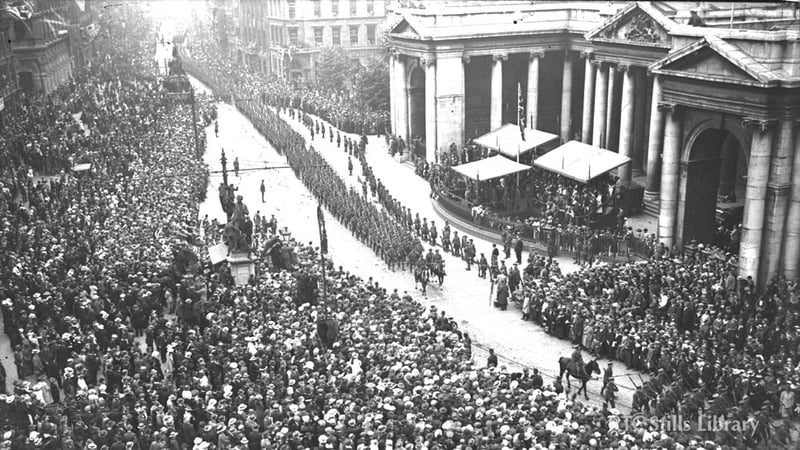

(i) After forty years as the representative voice of Irish nationalism, the Irish Parliamentary Party met its effective end in December 1918. Its leader John Dillon lost his seat to Eamon de Valera in East Mayo and Captain William Redmond, son of the party’s deceased leader, John, claimed the party’s only seat outside of Ulster. If the scale of this electoral retreat was remarkable, it was also one to which the party itself handsomely contributed. Not alone did many of the outgoing Irish Party MPs opted out of contesting the election, their party chose not to contest many of the seats – 25 in all – that they had vacated. In the end, aided also by Labour’s late withdrawal, Sinn Féin claimed 73 of the 105 seats allotted to Ireland in the Westminster Parliament. This was nothing less than a democratic revolution.

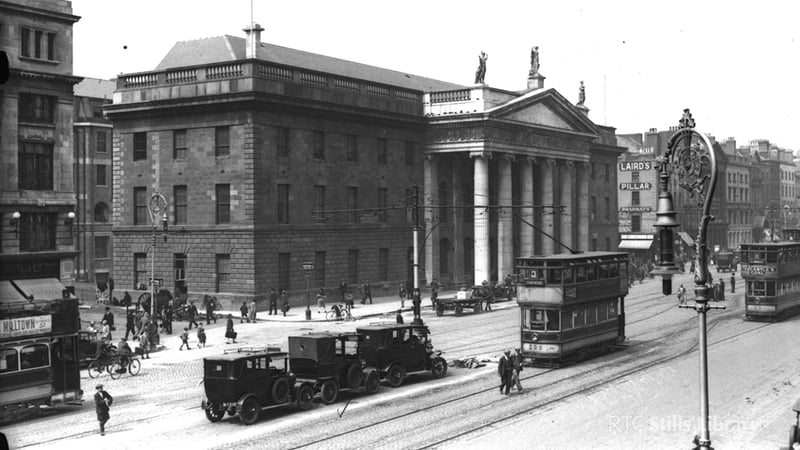

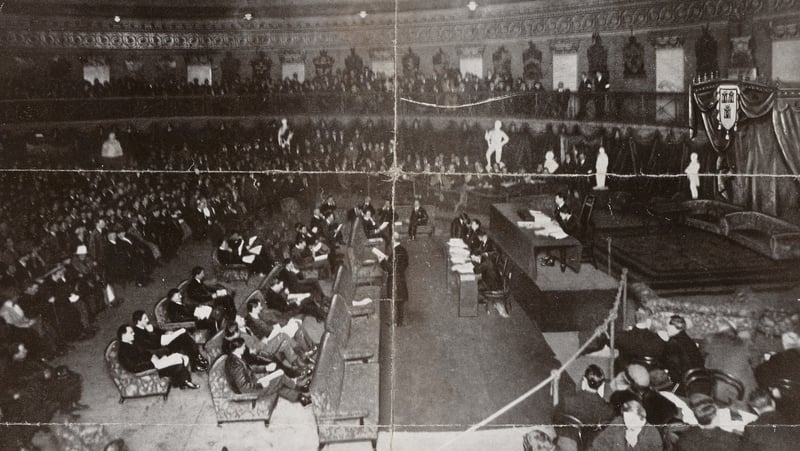

(ii) Sinn Féin’s election manifesto was unapologetically separatist. Its candidates were pledged abstain from Westminster, intent instead on creating a new ‘constituent assembly’ in Dublin. This would be established the following month, on 21 January 1919. It was known as ‘Dáil Eireann.’

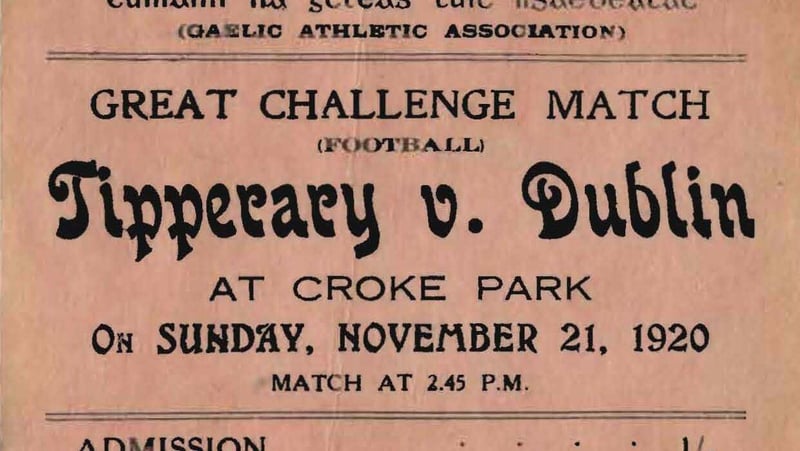

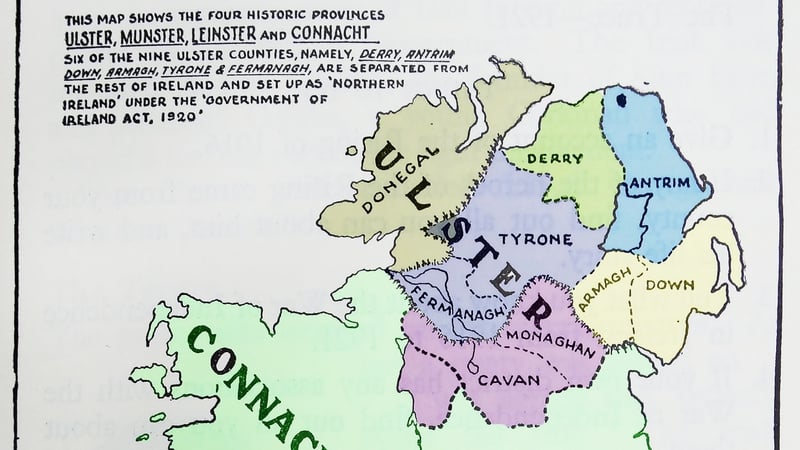

(iii) The result of the election fortified the position of Ulster unionism – they would win 23 of Ulster’s 37 seats - and exposed as fanciful the idea that the shared experience of sacrifice during the First World War might unite the divergent strands of Irish nationalism and unionism. Post-war and post election, the divisions in Irish political life not only remained; they appeared more entrenched than ever.

(iv) As unionism became ever more politically concentrated around Ulster, a development underlined by Edward Carson’s switch of constituency from Dublin University to Belfast Duncairn, southern unionism became increasingly isolated. Unionism survived in the south, but only in pockets and cut adrift from its stronghold in the north-east. The election therefore at once reflected and deepened divisions between northern and southern unionism, accelerating the drift towards some sort of partitionist settlement to the Irish question.

(v) UK-wide, the results of the election changed fundamentally the dynamics of the Anglo-Irish relationship and the role that the Irish question would subsequently play in British political life. For a start, Lloyd George was returned as the Prime Minister of a coalition government with a predominantly conservative cabinet. Furthermore, the election did much to destroy as a political force the Liberal Party that had, on three previous over the previous forty years – in 1886, 1893 and 1912 - put forward legislation to grant Home Rule to Ireland. With Sinn Féin abstaining from Westminster and the Liberals in retreat, the days of Irish nationalists exerting a guiding influence over the direction of British policy on Ireland were over.

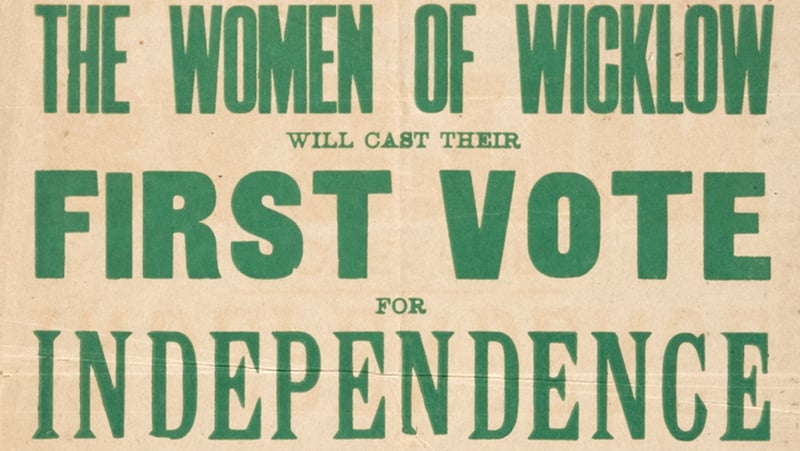

(vi) The election that was the first to confer the right to vote upon women (restricting it to those over 30 with a property qualification) was also the election that returned the first female MP to Westminster. Countess Markieviz, then languishing in Holloway Prison in England, was one of two female candidates to contest in Ireland, winning a seat for the St. Patrick’s constituency in Dublin. Standing on a Sinn Féin platform of abstention from Westminster, it was a seat she would not take.

Markievicz would subsequently hold the position of Minister for Labour in the newly-created Dáil Eireann that resulted from the election. A trailblazer for women in Irish politics she may have been, but more than six decades would pass before another woman would be appointed to an Irish cabinet position. In 1979, when Maire Geoghan Quinn became Minister for the Gaeltacht, one newspaper felt compelled to proclaim her a "modern-day Markievicz".

(vii) Finally, whatever its ramifications for the future unity of Ireland and the relationship between this island and that of its larger neighbouring island, the election itself was a watershed moment in Ireland’s democratic development. Put simply, more people had been afforded a right to vote that any point previously in Irish history: franchise reform had expanded the Irish electorate from 700,000 to just under 2 million. Following partition, universal suffrage - reducing the voting age for women to 21 – was introduced by the Irish Free State in 1922. Women in the newly-created Northern Ireland (and indeed the rest of Great Britain) would have to wait until 1928 for a similar change.

Mark Duncan is a Director of Century Ireland www.rte.ie/centuryireland

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ