San Diego’s shipping industry under pressure to electrify, nix diesel pollution

Monitoring suggests tugboats, ferries and cargo ships are major sources of cancer-causing diesel pollution in portside neighborhoods such as Barrio Logan

Massive cranes mounted on a Dole Food Co. cargo ship hoisted containers at the Port of San Diego on Thursday, powered not by the ocean-going vessel’s hulking diesel engines but electricity.

Before the port’s anchor-tenant started plugging its freighters into “shore power” at the Tenth Avenue Marine Terminal in Barrio Logan, pollution was noticeably worse, said Todd Post, lead mechanic at the terminal.

“My truck would be parked here with soot all over it,” said Post, a stevedore with the International Longshore and Warehouse Union Local 29, who was overseeing operations Thursday.

Industrial businesses at the port have repeatedly blamed heavy traffic on Interstate 5 and the San Diego-Coronado Bay Bridge for the pollution that’s long plagued nearby communities.

However, a historic effort launched in late 2018 to clean up air quality in low-income neighborhoods of color across California has recently turned up some perhaps unanticipated findings for San Diego and National City’s portside communities.

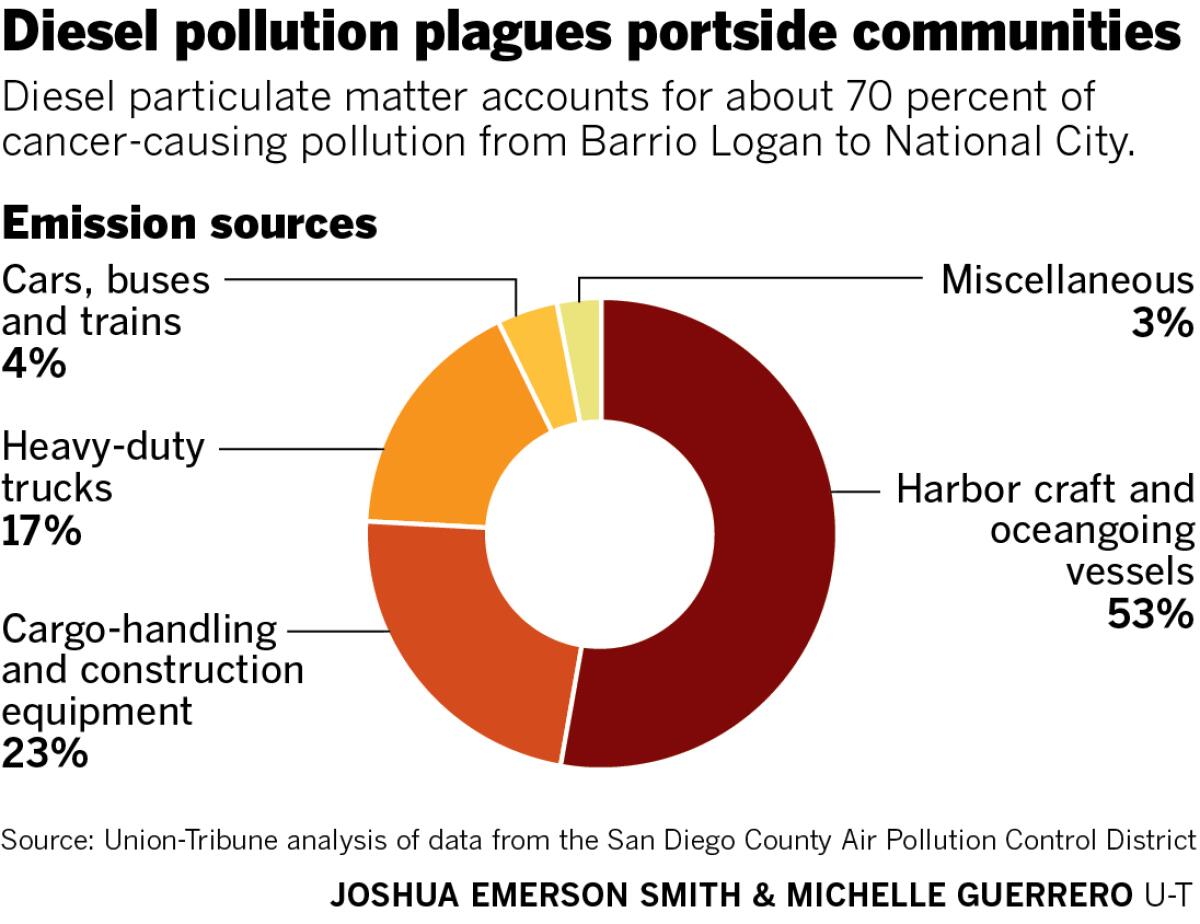

The lion’s share of cancer-causing air pollution appears to be coming from diesel emissions that can largely be traced back to tugboats, ferries and container ships operating at the port, according to a report released in April by the San Diego County Air Pollution Control District and the California Air Resources Board.

“That was something that did surprise me, the level to which the marine activities were contributing,” said air district Deputy Director Domingo Vigil, who joined the San Diego agency in November following a state-mandated overhaul.

The findings come as pressure ratchets on the port to adopt strict and binding timelines for its tenants to electrify everything from short-haul drayage trucks and forklifts to harbor and oceangoing vessels.

On Tuesday, the port’s seven-member board of commissioners will review a draft of the agency’s new Maritime Clean Air Strategy. The blueprint has faced increased scrutiny under the leadership of board chair Mike Zucchet, who also works as the general manager of the San Diego Municipal Employees Association.

“We need measurable goals and specific funding,” said Zucchet, who formerly served on the San Diego City Council. “This isn’t just aspirational.”

Officials with ILWU have expressed concerns that adopting overly strict standards for electrification could drive away business at the port and, with it, employment. They stressed the financial value of the maritime industry, which generates roughly $4.3 billion in economic activity and supports nearly 25,000 jobs.

Port tenants such as Dole in Barrio Logan and Pasha Automotive Services in west National City have said they’re open to phasing out diesel engines but cautioned that in many cases adopting battery-powered technology may not be feasible ahead of the state’s still-evolving mandates. As proof of their commitment, they point to participation in recent pilot projects that have funded a suite of new electric cargo-handling equipment.

“I think the port has and is proposing to go above and beyond what the state is currently requiring,” said Jack Monger, CEO of the trade group the Industrial Environmental Association. “But in all these discussions, we have to have some sort of assessment for what’s doable.”

Dole also helped invest in the port’s shore-power capabilities in 2014, which prevents large ocean-going vessels from belching plumes of toxic pollution while docked. The company has three container ships that move bananas, pineapples, mangos and other goods from South America to San Diego. Pasha, which operates one of the largest port terminals in the country for importing cars and trucks, has planned to adopt a bonnet system that would capture emissions at the smokestack.

Last month, Crowley Shipping released designs for an electric tugboat that is scheduled to operate in San Diego Bay by 2023. That effort, paid for in part with public funding, follows last year’s launch of the world’s first all-electric tug at a port in Istanbul.

Efforts to electrify diesel equipment haven’t come fast enough enough for community advocates.

Diane Takvorian, executive director of the Environmental Health Coalition, said industry has for too long profited while portside communities suffer from devastatingly high levels of asthma and cancer risk.

“It’s clear that most of the most damaging air pollution, diesel particulate matter, is coming from the Port of San Diego,” said Takvorian, who also sits on the state’s influential air board. “EHC is demanding the port step up and adopt a strategy to address that directly by electrifying all of the diesel-powered engines.”

Community impacts

Maritza Garcia’s mother grew up in Barrio Logan near Chicano Park. The largely Mexican-American community was forever changed in the 1960s when I-5 and the Coronado Bridge were built and the residential, bayfront neighborhood was rezoned to allow for heavy industrial activities.

By the time Garcia was a teenager, her mother was suffering from severe sinus and respiratory ailments and her grandfather had died of lung cancer.

“At first, I didn’t realize I was growing up in air pollution,” said Garcia, 27, who now lives in nearby Logan Heights. “Once I got to middle school, I saw a lot of my friends having breathing problems.”

Residents in Barrio Logan experience asthma at more than twice the national average, and the risk of cancer is in the 80th to 90th percentile, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Garcia said her home is constantly covered in black, sticky grime, often referred to as freeway dust. Someday, she would like to raise her own kids in the community but worries about the air pollution.

“Everything’s full of dusty muck,” she said. “In the morning you can see a layer of nastiness on our cars. For a while, we were using an air purifier in our house, but it was so expensive to keep up with the filters. It was ridiculous.”

In recent years, community advocates have targeted large freight trucks as the primary source of neighborhood pollution. Port officials largely agreed with this assessment, while maintaining that most of the big rigs passing through the community weren’t associated with maritime activities.

Pollution from diesel engines, such as those used in heavy-duty trucking, also contributes to fine particulate matter, known as PM2.5, which when inhaled exacerbates conditions such as asthma and heart disease.

However, recent air monitoring has found that more than half of such pollution comes from commercial cooking and construction activities, according to the air district recent report. The remaining share of PM2.5 emissions are driven mostly by freight and passenger vehicles, as well as tugboats, oceangoing vessels and other operations at the port.

Millions of dollars in state funding has already started flowing to San Diego to help curb such pollution. Resources are expected to benefit many neighborhood businesses, especially as regulators pinpoint specific pollution hotspots.

At the same time, the state has increasingly ramped up efforts to electrify freight trucks and passenger vehicles. Gov. Gavin Newsom signed an executive order in September calling for all new cars sold in the state to be zero-emission by 2035.

The directive also calls for the air board to draft regulations to ensure that “where feasible” all freight trucks and other heavy-duty vehicles be zero-emission by 2045, a mandate that goes into effect for short-haul drayage trucks by 2035.

Still, electrifying harbor craft and other maritime activities may prove more challenging.

“We know what kind of technology needs to be implemented to expand shore power,” said Jason Giffen, vice president of planning, environment and government relations at the port, “but with that comes both infrastructure as well as financing challenges. It’s a very sizable investment.”

Political shift

In December, commissioners declined to approve a deal between port staff and the Mitsubishi Cement Co. that would have significantly increased the number of heavy-duty trucks rolling through Barrio Logan.

Mitsubishi wanted to operate a cement storage and distribution facility at the Tenth Avenue Marine Terminal that would have added about 176 truck trips a day onto the roughly 148 trips already occurring there.

Board members and others wanted Mitsubishi to commit to a specific timeline for phasing in electric trucks, with community advocates pushing for an all-electric fleet by 2030.

The company balked at the notion.

“Discussions with Mitsubishi are ongoing,” Zucchet said. “Everybody supports every inch of that project except one thing, which is the significant diesel truck trips it will generate.”

The dust-up highlights a political shift around port operations over the last few years, with state and local officials increasingly looking to clamp down on diesel and other emissions.

Shortly after the state launched its campaign in 2018 to clean up air pollution in disadvantaged communities, then-Assemblyman Todd Gloria, now mayor of San Diego, spearheaded a bill to overhaul the governing board of San Diego’s local air district.

Since 1955, the air district has been governed by the region’s five county supervisors. Now, under the new law, the agency has 11 representatives, including two county supervisors, six elected city officials and three members of the public.

The three public seats are reserved for a physician or public health professional, an environmental justice advocate who works with disadvantaged communities, and someone with scientific or technical background in air pollution.

The agency now plans to explore one of the newest approaches to cutting emission, what’s known as an “indirect source rule.” That would alter the traditional delineation of authority where the state air board regulates emission from mobile sources, such as cars and trucks, and the 35 local air districts focus on stationary sources, such as factories.

On Friday, the South Coast Air Quality Management District approved the state’s first indirect-sources rule that will hold the Amazon-style warehouses that’ve proliferated in parts of the Inland Empire accountable for associated truck traffic.

Regulators in San Diego have been watching developments closely, saying that an indirect source rule for port operators could be in the works. The strategy could mean even tougher regulations for port operators that rely on freight trucks to move their goods.

“It’s certainly a difficult issue to bring up because of all these different ramifications but ultimately something we have to take a look at,” said the air district’s Vigil.

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.