Explainer | How will Malaysia and China’s maritime consultation mechanism affect the South China Sea dispute?

- The recently announced bilateral mechanism has given rise to questions over the disputed waterway, where both countries have overlapping claims

- A recent Malaysian foreign policy update has proposed turning the South China Sea into a region of peace, friendship and trade

In a meeting between Malaysia’s Foreign Minister Saifuddin Abdullah and China’s State Councillor Wang Yi, the Chinese official announced “a new platform for dialogue and cooperation” for maritime issues.

Saifuddin said the mechanism would be led by the foreign ministries of both nations, which enjoy close trade ties and mark 45 years of diplomatic relations this year.

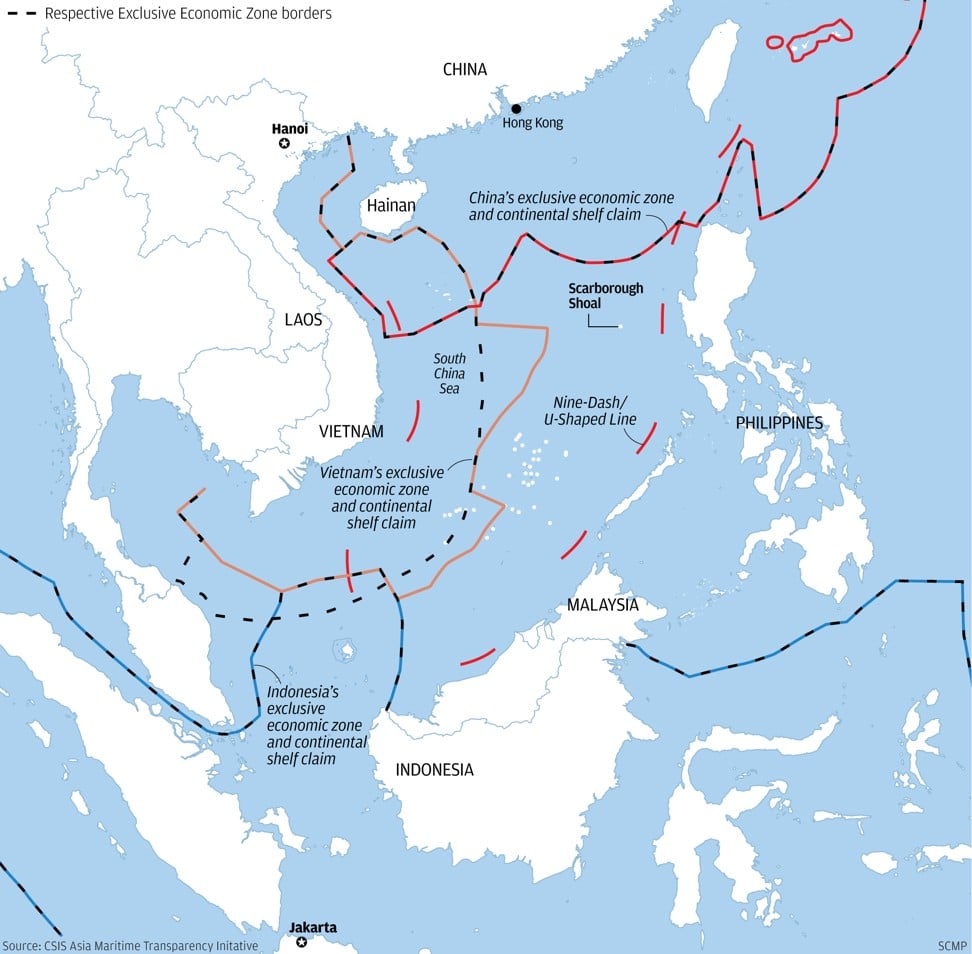

The South China Sea, one of the world’s busiest and most resource-rich waterways, is currently the subject of territorial disputes between four Southeast Asian countries – Malaysia, Brunei, the Philippines, and Vietnam – and Beijing.

Mahathir to update Malaysia’s foreign policy, including on South China Sea and international Muslim cooperation

However, the proposed bilateral mechanism is not a platform to discuss territorial and maritime claims in the South China Sea, maintained Malaysian sources close to the discussion: “Malaysia is consistent that the Asean route is the only way to resolve any disputes on the South China Sea. The mechanism should not be equated to bilateral negotiations on the South China Sea.”

Malaysia is consistent that the Asean route is the only way to resolve any disputes on the South China Sea

Last week, Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad unveiled a new “guiding framework” for the country’s foreign policy, stressing that the government would continue its non-aligned stance towards major powers and announcing plans to take the lead in fostering cooperation in the Muslim world.

As part of the framework, Mahathir proposed the non-militarisation of the disputed waterway, and for it to be turned into a region of peace, friendship and trade.

“Essentially, the South China Sea should be a sea of cooperation, connectivity and community-building and not confrontation or conflict. This is in line with the spirit of Zone of Peace, Freedom and Neutrality (ZOPFAN). Malaysia will actively promote this vision in Asean,” the framework said.

The ZOPFAN agreement to “keep Southeast Asia free from any form or manner of interference by outside powers” was signed by Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand and Singapore in 1971.

The United States, Southeast Asia’s dominant naval power, has consistently challenged Chinese claims to the area, with Washington frequently running freedom of navigation operations in those waters.

Explained: South China Sea dispute

In 2016 the Philippines signed a South China Sea bilateral consultation mechanism with China after President Rodrigo Duterte assumed office. The two countries have discussed joint exploration deals in the contested waters, although nothing concrete has been announced.

WHAT ARE MALAYSIA’S CLAIMS IN THE SOUTH CHINA SEA?

As per the United Nations Convention for the Law of the Sea, Malaysia claims the waters and seabed that extend 200 nautical miles from its coast. This includes an extended continental shelf claim it jointly submitted with Vietnam in 2009.

China objects to most of Malaysia’s maritime claims because they fall within its “nine-dash line”, says Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative director Greg Poling. The geographical marker used to assert its claim stretches as far as 2,000km from the Chinese mainland, reaching waters close to Malaysia, Vietnam and the Philippines.

Malaysia also lays claim to 12 islands in the Spratlys archipelago of islands, reefs and shoals, and occupies five. China, however, claims to the entire Spratlys formation – and, says Poling, also claims the Luconia Shoals and James Shoal as part of the Spratlys even though they are underwater and therefore “legally part of Malaysia’s continental shelf”.

The Southeast Asian nation also has five offshore stations in the Spratlys, which are patrolled by the country’s armed forces and the Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency.

These include Swallow Reef, where the Royal Malaysian Navy maintains a presence, and which has been turned into an artificial island with a holiday resort.

HOW HAS CHINA REACTED TO MALAYSIA’S CLAIMS?

China’s reactions have changed over the years, says Joseph Liow Chin Yong of Singapore’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, although it generally rejects any other claims at odds with its own.

Unlike Vietnam and the Philippines, China’s dealings with Malaysia over the South China Sea issue have been far more stable.

Will backlash force Duterte to retreat from South China Sea oil exploration deal with Beijing?

“However, Chinese vessels are patrolling further and further south. They have appeared off the coast of East Malaysia, and even [Malaysian national oil and gas company] Petronas is concerned about the activities of these ships in the vicinity of their offshore drilling facilities,” Liow said.

China has long maintained the dispute can only be resolved via separate bilateral discussions between Beijing and each of the four Southeast Asian claimants.

Negotiations for a Code of Conduct for the area are ongoing, but the code is “designed to reduce tensions, not resolve the dispute,” says Ian Storey, senior fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore.

WILL A BILATERAL CONSULTATION MECHANISM HELP RESOLVE THE DISPUTE?

The mechanism is unlikely to make any strides towards resolving the dispute, experts say, pointing out that it does not touch upon the South China Sea.

However, says Storey, its establishment not only reflects China’s preferred method for dealing with the dispute, but also strengthens the narrative that “Asian countries are working to resolve Asian security problems and that there’s no need for ‘outsiders’ such as the United States to get involved”.

These mechanisms are often more about optics and perception, according to experts, such as in the case of the Philippines’ bilateral consultation mechanism – which Poling says hasn’t shown “much sign of progress”.

“The mechanism to date is more about creating a perception of progress, which is politically useful to both sides. But the fact is that Beijing is no closer to compromising its claims now than it was when President Duterte took office,” he says – and the same is likely to apply to Malaysia as well, given the “threatening behaviour” of Chinese Coast Guard vessels towards Malaysian oil and gas operations.

If the mechanism will indeed not touch on South China Sea matters, Liow says: “It will be what it will be – a consultation mechanism, [to] talk shop!”