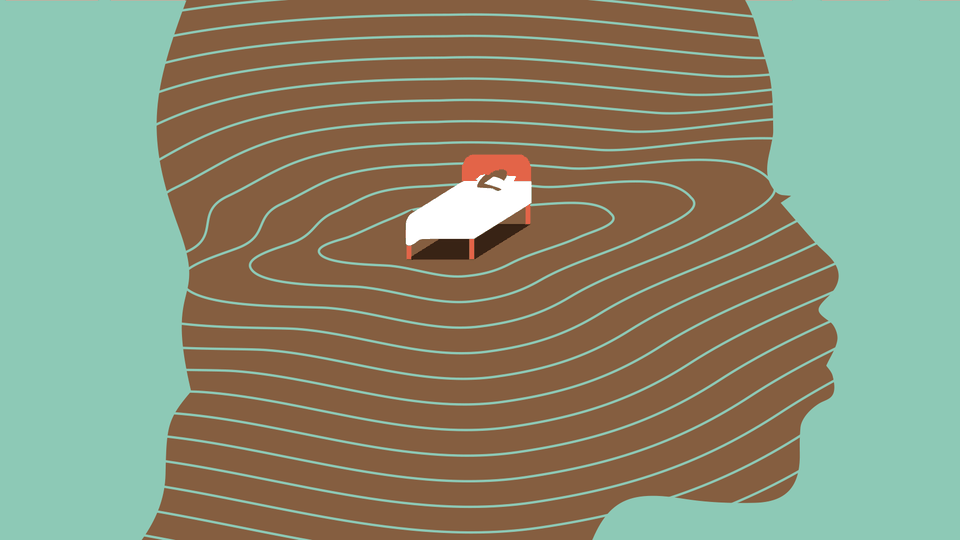

Whenever I think of my mother, I picture a queen-size bed with her lying in it, a practiced stillness filling the room. For months on end, she colonized that bed like a virus, the first time when I was a child and then again when I was a graduate student.

The first time, I was sent to Ghana to wait her out. While there, I was walking through Kejetia Market with my aunt when she grabbed my arm and pointed. “Look, a crazy person,” my aunt said in Twi. “Do you see? A crazy person.”

I was mortified. My aunt was speaking loudly, and the man, tall with dust caked into his dreadlocks, was within earshot. “I see, I see,” I answered in a low hiss. The man continued past us, mumbling to himself as he waved his hands about in gestures that only he could understand. My aunt nodded, satisfied, and we kept walking through the hordes of people gathered in the market until we reached the stall where we would spend the rest of the morning attempting to sell knockoff handbags. In my three months there, we sold only four bags.

Even now, I don’t completely understand why my aunt singled the man out to me. Maybe she thought there were no crazy people in America, that I had never seen one before. Or maybe she was thinking about my mother, about the real reason I was stuck in Ghana that summer, sweating in a stall with an aunt I hardly knew while my mother healed at home in Alabama. I was 11, and I could see that my mother wasn’t sick, not in the ways that I was used to. I didn’t understand what my mother needed healing from. I didn’t understand, but I did. And my embarrassment at my aunt’s loud gesture had as much to do with my understanding as it did with the man who had passed us by. My aunt was saying, That. That is what crazy looks like. But instead what I heard was my mother’s name. What I saw was my mother’s face, still as lake water, Pastor John’s hand resting gently on her forehead, his prayer a light hum that made the room buzz. I’m not sure I know what crazy looks like, but even today when I hear the word, I picture a split screen, the dreadlocked man in Kejetia on one side, my mother lying in bed on the other. I think about how no one at all reacted to that man in the market, not in fear or disgust, nothing, save my aunt, who wanted me to look. He was, it seemed to me, at perfect peace, even as he gesticulated wildly, even as he mumbled.

But my mother, in her bed, infinitely still, was wild inside.

The second time it happened, I got a phone call while I was working in my lab at Stanford. I’d had to separate two of my mice because they were ripping each other to bits in that shoebox of a home we kept them in. I found a piece of flesh in one corner of the box, but I couldn’t tell which mouse it had come from. Both were bleeding and frenzied, scurrying away from me when I tried to grab them even though there was nowhere to run.

“Look, Gifty, she hasn’t been to church in nearly a month,” Pastor John said to me. “I’ve been calling the house, but she won’t pick up. I go by sometimes and make sure she’s got food and everything, but I think—I think it’s happening again.”

I didn’t say anything. The mice had calmed down considerably, but I was still shaken by the sight of them and worried about my research. Worried about everything.

“Gifty?” Pastor John said.

“She should come stay with me.”

I’m not sure how the pastor got my mother on the plane, because when I picked her up at SFO she looked completely vacant, her body limp. I imagined Pastor John folding her up the way you would a jumpsuit, arms crossed over the chest in an X, legs pulled up to meet them, then tucking her safely into a suitcase complete with a handle with care sticker before passing her off to a flight attendant.

I gave her a stiff hug and she shrank from my touch. I took a deep breath. “Did you check a bag?” I asked.

“Daabi,” she said.

“No bags, great—we can go straight to the car.” The saccharine cheeriness of my voice annoyed me so much that I bit my tongue in an attempt to bite it back. I felt a prick of blood and sucked it away.

She followed me to my Prius. Under better circumstances she would have made fun of my car, an oddity to her after years of Alabama pickup trucks and SUVs. “Gifty, my bleeding heart,” she sometimes called me. I don’t know where she’d picked up the phrase, but I figured it was probably used derogatorily by Pastor John and the various TV preachers she liked to watch to describe people who, like me, had defected from Alabama to live among the sinners of the world, presumably because the excessive bleeding of our hearts made us too weak to tough it out among the hardy, the chosen of Christ in the Bible Belt. She loved Billy Graham, who said things like “A real Christian is the one who can give his pet parrot to the town gossip.”

Cruel, I thought when I was a child, to give away your pet parrot.

The funny thing about the phrases that my mom picked up is that she always got them a little wrong. I was her bleeding heart, not a bleeding heart. It’s a crime shame, not a crying shame. She had a slight southern accent that tinted her Ghanaian one.

In the car, my mother stared out of the passenger-side window. I tried to imagine the scenery the way she might be seeing it. When I’d first arrived in California, everything had looked so beautiful to me. Even the grass, yellowed, scorched from the sun and the seemingly endless drought, had looked otherworldly. This must be Mars, I thought, because how could this be America too? I pictured the drab green pastures of my childhood, the small hills we called mountains. The vastness of this western landscape overwhelmed me. I’d come to California because I wanted to get lost, to find. In college, I’d read Walden because a boy I found beautiful found the book beautiful. I understood nothing but highlighted everything, including this: “Not till we are lost, in other words, not till we have lost the world, do we begin to find ourselves, and realize where we are and the infinite extent of our relations.”

If my mother was moved by the landscape too, I couldn’t tell. We lurched forward in traffic and I caught the eye of the man in the car next to ours. He quickly looked away, then looked back, then away again. I wanted to make him uncomfortable, or maybe just to transfer my own discomfort to him, so I kept staring. I could see in the way that he gripped the steering wheel that he was trying not to look at me again. His knuckles were pale, veiny, rimmed with red. He gave up, shot me an exasperated look, mouthed, What? I’ve always found that traffic on a bridge brings everyone closer to their own personal edge. Inside each car, a snapshot of a breaking point, drivers looking out toward the water and wondering, What if? Could there be another way out? We scooted forward again. In the scrum of cars, the man seemed almost close enough to touch. What would he do if he could touch me? If he didn’t have to contain all of that rage inside his Honda Accord, where would it go?

“Are you hungry?” I asked my mother, finally turning away.

She shrugged, still staring out of the window. The last time this happened, she’d lost 70 pounds in two months. When I came back from my summer in Ghana, I hardly recognized her, this woman who had always found skinny people offensive, as though a kind of laziness or failure of character kept them from appreciating the pure joy that is a good meal. Then she joined their ranks. Her cheeks sank; her stomach deflated. She hollowed, disappeared.

I was determined not to let that happen again. I’d bought a Ghanaian cookbook online to make up for the years I’d spent avoiding my mother’s kitchen, and I’d practiced a few of the dishes in the days leading up to my mother’s arrival, hoping to perfect them before I saw her. I’d bought a deep fryer, even though my grad-student stipend left little room in my budget for extravagances like bofrot or plantains.

Fried food was my mother’s favorite. Her mother had made fried food in a cart on the side of the road in Kumasi. My grandmother was a Fante woman from Abandze, a sea town, and she was notorious for despising Asantes, so much so that she refused to speak Twi, even after 20 years of living in the Asante capital. If you bought her food, you had to listen to her language.

“We’re here,” I said, rushing to help my mother get out of the car. She walked a little ahead of me, even though she’d never been to this apartment before. She’d visited me in California only a couple of times.

“Sorry for the mess,” I said, but there was no mess. None that my eyes could see anyway, but my eyes were not hers. Every time she visited me over the years, she’d sweep her finger along things it never occurred to me to clean—the backs of the blinds, the hinges of doors—then present the dusty, blackened finger to me in accusation, and I could do nothing but shrug.

“Cleanliness is godliness,” she used to say. “Cleanliness is next to godliness,” I would correct, and she would scowl at me. What was the difference?

I pointed her toward the bedroom, and, silently, she crawled into bed and drifted off to sleep.

As soon as I heard the sound of soft snoring, I snuck out of the apartment and went to check on my mice. Though I had separated them, the mouse with the largest wounds was hunched over from pain in the corner of the box. Watching him, I wasn’t sure he would live much longer. It filled me with an inexplicable sorrow, and when my lab mate, Han, found me 20 minutes later, crying in the corner of the room, I was too mortified to admit that the thought of a mouse’s death was the cause of my tears.

“Bad date,” I told Han. A look of horror passed over his face as he mustered up a few pitiful words of comfort, and I could imagine what he was thinking: I went into the hard sciences so that I wouldn’t have to be around emotional women. My crying turned to laughter, loud and phlegmy, and the look of horror on his face deepened until his ears flushed as red as a stop sign. I stopped laughing and rushed out of the lab and into the restroom, where I stared at myself in the mirror. My eyes were puffy and red; my nose looked bruised, the skin around the nostrils dry and scaly from the tissues. “Get ahold of yourself,” I said to the woman in the mirror, but doing so felt cliché, like I was reenacting a scene from a movie, and so I started to feel like I didn’t have a self to get ahold of, or rather that I had a million selves, too many to gather. One was in the bathroom; another, in the lab staring at my wounded mouse, an animal about whom I felt nothing at all, yet whose pain had reduced me somehow. Or multiplied me. Another self was thinking about my mother.

When I returned to the lab, Han looked up from his work. “Hey,” he said.

“Hey.”

Though we’d been sharing the space for months, we hardly ever said more than this to each other, except for today, when he’d found me crying. Han’s ears usually burned bright red if I tried to push our conversation past that initial greeting.

I drove back to my apartment. In the bedroom, my mother still lay underneath a cloud of covers. A purr floated out from her lips. I’d been living alone for so long that even that soft noise, hardly more than a hum, unnerved me. I’d forgotten what it was like to live with my mother, to care for her. For a long time, most of my life, in fact, it had been just me and her, but this pairing was unnatural. She knew it and I knew it, and we both tried to ignore what we knew to be true—there used to be four of us, then three, two. When my mother goes, whether by choice or not, there will be only one.

When there were four of us, I was too young to appreciate it. My mother used to tell stories about my father. At 6 feet 4 inches, he was the tallest man she’d ever seen; she thought he was maybe even the tallest man in all of Kumasi. He used to hang around her mother’s food stand, joking with my grandmother about her stubborn Fante, coaxing her into giving him a free baggie of achomo, which he called chin chin like the Nigerians in town did. My mother was 30 when they met, 31 when they married. She was already an old maid by Ghanaian standards, but she said God had told her to wait, and when she met my father, she knew what she’d been waiting for.

She called him the Chin Chin Man, like her mother called him. And when I was very little and wanted to hear stories about him, I’d tap my chin until my mother complied. “Tell me about Chin Chin,” I’d say. I almost never thought of him as my father.

The Chin Chin Man was six years older than she was. Coddled by his own mother, he’d felt no need to marry. He had been raised Catholic, but once my mother got ahold of him, she dragged him to the Christ of her Pentecostal church. The same church where the two of them were married in the sweltering heat, with so many guests that they stopped counting after 200.

They prayed for a baby, but month after month, year after year, no baby came. It was the first time my mother ever doubted God. After I am worn out, and my Lord is old, shall I have pleasure?

“You can have a child with someone else,” she offered, taking initiative in God’s silence, but the Chin Chin Man laughed at the suggestion. My mother spent three days fasting and praying in the living room of my grandmother’s house. She must have looked as frightful as a witch, smelled as horrid as a stray dog, but when she left her prayer room, she said to my father, “Now,” and he went to her and they lay together. Nine months to the day later, my brother, Nana, my mother’s Isaac, was born.

My mother used to say, “You should have seen the way the Chin Chin Man smiled at Nana.” His entire face was in on it. His eyes brightened; his lips spread back until they were touching his ears, which lifted. Nana’s face returned the compliment, smiling in kind. My father’s heart was a light bulb, dimming with age. Nana was pure light.

Nana could walk at seven months. That’s how they knew he would be tall. He was the darling of their compound. Neighbors used to request him at parties. “Would you bring Nana by?” they’d say, wanting to fill their apartment with his smile, his bowlegged baby dancing.

Every street vendor had a gift for Nana: a bag of koko, an ear of corn, a tiny drum. “What couldn’t he have?” my mother wondered. Why not the whole world? She knew the Chin Chin Man agreed. Nana, beloved and loving, deserved the best. But what was the best that the world had to offer? For the Chin Chin Man, it was my grandmother’s achomo, the bustle of Kejetia, the red clay, his mother’s fufu pounded just so. It was Kumasi, Ghana. My mother was less certain of this. She had a cousin in America who sent money and clothes back to the family somewhat regularly, which surely meant there were money and clothes in abundance across the Atlantic. With Nana’s birth, Ghana had started to feel too cramped. My mother wanted room for him to grow.

They argued and argued and argued, but the Chin Chin Man’s easygoing nature meant he let my mother go easy, and so after a week of arguing she applied for the green-card lottery. It was a time when not many Ghanaians were immigrating to America, which is to say you could enter the lottery and win. My mother found out that she had been randomly selected for permanent residency in America a few months later. She packed what little she owned, bundled up baby Nana, and moved to Alabama, a state she had never heard of, but where she planned to stay with her cousin, who was finishing up her Ph.D. The Chin Chin Man would follow later, after they had saved up enough money for a second plane ticket and a home of their own.

My mother slept all day and all night, every day, every night. She was immovable. Whenever I could, I would try to persuade her to eat something. I’d taken to making koko, my favorite childhood meal. I’d had to go to three different stores to find the right kind of millet, the right kind of corn husks, the right peanuts to sprinkle on top. I hoped the porridge would go down easily. I’d leave a bowl of it by her bedside in the morning before I went to work, and when I returned the top layer would be covered in film; the layer underneath had hardened so that when I scraped it into the sink, I felt the effort of it.

My mother’s back was always turned to me. It was like she had an internal sensor for when I’d be entering the room to deliver the koko. I could picture the movie montage of us, the days spelled out at the bottom of the screen, my outfits changing, our actions the same.

After about five days of this, I entered the room and my mother was awake and facing me.

“Gifty,” she said as I set the bowl of koko down. “Do you still pray?”

It would have been kinder to lie, but I wasn’t kind anymore. Maybe I never had been. I vaguely remembered a childhood kindness, but maybe I was conflating innocence and kindness. I felt so little continuity between who I was as a young child and who I was now that it seemed pointless to even consider showing my mother something like mercy. Would I have been merciful when I was a child?

“No,” I answered.

When I was a child, I prayed. I studied my Bible and kept a journal with letters to God. I was a paranoid journal keeper, so I made code names for all the people in my life I wanted God to punish.

Reading the journal makes it clear that I was a real “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” kind of Christian, and that I believed in the redemptive power of punishment. For it is said, that when that due Time, or appointed Time comes, their Foot shall slide. Then they shall be left to fall as they are inclined by their own Weight.

The code name I gave my mother was the Black Mamba, because we’d just learned about the snake in school. The movie the teacher showed us that day featured a seven-foot-long snake that looked like a slender woman in a skintight leather dress, slithering across the Sahara in pursuit of a bush squirrel.

In my journal, the night we learned about the snake, I wrote:

Dear God,

The Black Mamba has been really mean to me lately. Yesterday she told me that if I didn’t clean my room no one would want to marry me.

My brother, Nana, was code-named Buzz. I don’t remember why now. In the first few years of my journal-keeping, Buzz was my hero:

Dear God,

Buzz ran after the ice-cream truck today. He bought a firecracker popsicle for himself and a Flintstones push pop for me.

Or:

Dear God,

At the rec center today, none of the other kids wanted to be my partner for the three-legged race because they said I was too little, but then Buzz came over and he said that he would do it! And guess what? We won and I got a trophy.

Sometimes he annoyed me, but back then, his offenses were innocuous, trivial.

Dear God,

Buzz keeps coming into my room without knocking! I can’t stand him!

But after a few years, my pleas for God’s intervention became something else entirely.

Dear God,

When Buzz came home last night he started yelling at TBM and I could hear her crying, so I went downstairs to look even though I was supposed to be in bed. (I’m sorry.) She told him to keep quiet or he would wake me, but then he picked up the TV and smashed it on the floor and punched a hole in the wall and his hand was bleeding and TBM started crying and she looked up and saw me and I ran back to my room while Buzz screamed get the fuck out of here you nosy cunt. (What is a cunt?)

I was 10 when I wrote that entry. I was smart enough to use the code names and make note of new vocabulary words but not smart enough to see that anyone who could read could easily crack my code. I hid the journal under my mattress, but because my mother is a person who thinks to clean underneath a mattress, I’m sure she must have found it at some point. If she did, she never mentioned it. After the broken-television incident, my mother had run up to my bedroom and locked the door while Nana raved downstairs. She grabbed me close and pulled the both of us down onto our knees behind the bed while she prayed in Twi.

Awurade, bɔ me ba barima ho ban. Awurade, bɔ me ba barima ho ban. Lord, protect my son. Lord, protect my son.

“You should pray,” my mother said then, reaching for the koko. I watched her eat two spoonfuls before setting it back down on the nightstand.

“Is it okay?” I asked.

She shrugged, turned her back to me once more.

I went to the lab. Han wasn’t there, so he hadn’t turned the thermostat down low as he usually did. I set my jacket on the back of a chair, got myself ready, then grabbed a couple of my mice to anesthetize and prep them for surgery. I shaved the fur from the tops of their heads until I saw their scalps. I carefully drilled into those, wiping the blood away, until I found the bright red of their brains, the chests of the rodents expanding and deflating mechanically as they breathed their unconscious breaths.

Though I had done this millions of times, it still awed me to see a brain. To know that if I could understand this little organ inside this one tiny mouse, that understanding still wouldn’t speak to the full intricacy of the comparable organ inside my own head. And yet I had to try to understand and to extrapolate to those of us who made up the species Homo sapiens, the most complex animal, the only animal who believed he had transcended his kingdom, as one of my high-school biology teachers used to say. That belief, that transcendence, was held within this organ itself. Infinite, unknowable, soulful, perhaps even magical. I had traded the Pentecostalism of my childhood for this new religion, this new quest, knowing that I would never fully know.

I was a sixth-year Ph.D. candidate in neuroscience at the Stanford University School of Medicine. My research was on the neural circuits of reward-seeking behavior. Once, on a date during my first year of grad school, I had bored a guy stiff by trying to explain to him what I did all day. He’d taken me to Tofu House in Palo Alto, and as I watched him struggle with his chopsticks, losing several pieces of bulgogi to the napkin in his lap, I’d told him all about the medial prefrontal cortex, nucleus accumbens, 2-photon Ca2+ imaging.

“We know that the medial prefrontal cortex plays a crucial role in suppressing reward-seeking behavior; it’s just that the neural circuitry that allows it to do so is poorly understood.”

I’d met him on OkCupid. He had straw-blond hair, skin perpetually at the end phase of a sunburn. He looked like a SoCal surfer. The entire time we’d messaged back and forth, I’d wondered if I was the first Black girl he’d ever asked out, if he was checking some kind of box off his list of new and exotic things he’d like to try, like the Korean food in front of us, which he had already given up on.

“Huh,” he said. “Sounds interesting.”

Maybe he’d expected something different. There were only five women in my lab of 28, and I was one of three Black Ph.D. candidates in the entire med school. He never called me back.

From then on, I told dates that my job was to get mice hooked on cocaine before taking it away from them.

Two in three asked the same question: “So do you just, like, have a ton of cocaine?” I never admitted that we’d switched from cocaine to Ensure. It was easier to get and sufficiently addictive for the mice. I relished the thrill of having something interesting and illicit to say to these men, most of whom I would sleep with once and then never see again. It made me feel powerful to see their names flash across my phone screen hours, days, weeks after they’d seen me naked, after they’d dug their fingernails into my back, sometimes drawing blood. Reading their texts, I liked to feel the marks they’d left. I felt like I could suspend the men there, just names on my phone screen, but after a while, they stopped calling, moved on, and then I would feel powerful in their silence. At least for a little while. I wasn’t accustomed to power in relationships, power in sexuality. I had never been asked on a date in high school. Not once. I wasn’t cool enough, white enough, enough. In college, I had been shy and awkward, still molting the skin of a Christianity that insisted I save myself for marriage, that left me fearful of men and of my body. Every other sin a person commits is outside the body, but the sexually immoral person sins against his own body.

I watched my mice groggily spring back to life, recovering from the anesthesia and woozy from the painkillers I’d given them. I’d injected a virus into the nucleus accumbens and implanted a lens in their brain so that I could see their neurons firing as I ran my experiments. I sometimes wondered if they noticed the added weight they carried on their heads, but I tried not to think thoughts like that, tried not to humanize them, because I worried that would make doing my work harder. I cleaned up my station and went to my office to try to do some writing. I was supposed to be working on a paper, presumably my last before graduating. The most difficult part, putting the figures together, usually took me only a few weeks or so, but I had been dragging things out. Running my experiments over and over again, until the idea of stopping, of writing, of graduating, seemed impossible. I’d put a little warning on the wall above my desk to whip myself into shape: 20 minutes of writing a day or else. Or else what? I wondered. Anyone could see it was an empty threat. After 20 minutes of doodling, I pulled out the journal entry from years ago that I kept hidden in the bowels of my desk to read on those days when I was feeling low and lonely and useless and hopeless. Or when I wished I had a job that paid me more than a $17,000 stipend to stretch through a quarter in this expensive college town.

Dear God,

Buzz is going to prom and he has a suit on! It’s navy blue with a pink tie and a pink pocket square. TBM had to order the suit special cuz Buzz is so tall that they didn’t have anything for him in the store. We spent all afternoon taking pictures of him, and we were all laughing and hugging and TBM was crying and saying, “You’re so beautiful,” over and over. And the limo came to pick Buzz up so he could pick his date up and he stuck his head out of the sunroof and waved at us. He looked normal. Please, God, let him stay like this forever.

My brother died of a heroin overdose three months later.

“I’m pretty, right?” I once asked my mother. We were standing in front of the mirror while she put her makeup on for work. I don’t remember how old I was, only that I wasn’t allowed to wear makeup yet. I had to sneak it when my mother wasn’t around, but that wasn’t too hard to do. My mother worked all the time. She was never around.

“What kind of question is that?” she asked. She grabbed my arm and jerked me toward the mirror. “Look,” she said, and at first I thought she was angry at me. I tried to look away, but every time my eyes fell, my mother would jerk me to attention once more. She jerked me so many times, I thought my arm would come loose from the socket.

“Look at what God made. Look at what I made,” she said in Twi.

We stared at ourselves in the mirror for a long time. We stared until my mother’s work alarm went off, the one that told her it was time to leave one job in order to get to the other. She finished putting her lipstick on, kissed her reflection in the mirror, and rushed off. I kept staring at myself after she left, kissing my own reflection.

This story has been excerpted from Yaa Gyasi’s forthcoming novel, Transcendent Kingdom.