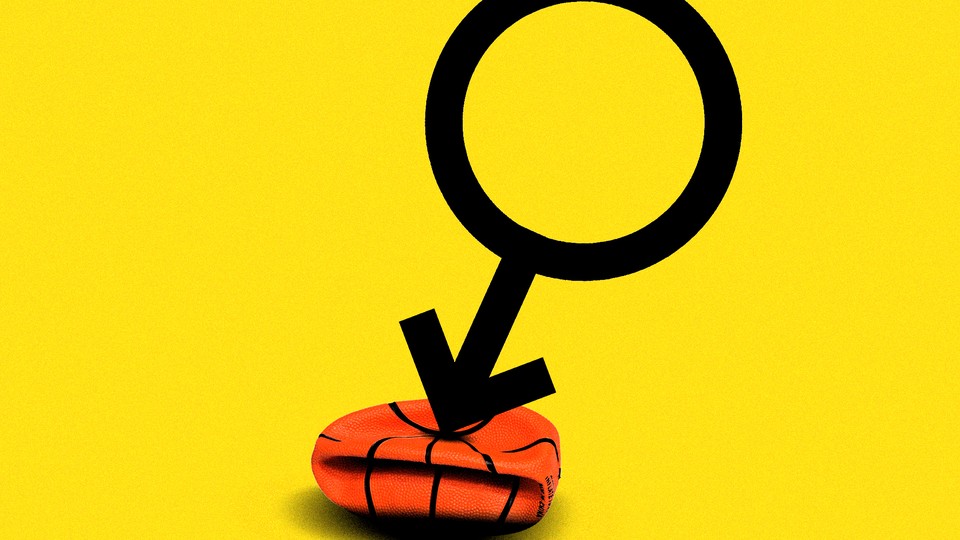

The Title IX Loophole That Hurts NCAA Women’s Teams

A little-known Supreme Court ruling makes it legal for the league to promote its men’s and women’s teams unequally.

When Sedona Prince, a center on the University of Oregon women’s basketball team, shared a TikTok from the NCAA women’s basketball tournament earlier this month, it went viral. Her video compared the women’s weight room in San Antonio—a single small rack of dumbbells and a stack of yoga mats—with what the men’s teams were provided at their tournament, in Indianapolis: a gym-size room full of squat racks, benches, barbells, and racks of heavy plates. Soon after, players and coaches from several teams began posting their own photos on social media: a buffet of steak and shrimp for the men, prepackaged meals for the women. Swag bags full of celebratory gear blaring March Madness and The Big Dance for the men—what appeared to be a few standard-issue items without any reference to the tournament for the women.

After the firestorm of attention to the discrepancies, the NCAA apologized, provided the women with a proper weight room, defended the swag bags as equal in value, and said it had addressed the food situation. The NCAA’s president, Mark Emmert, told reporters: “I want to be really clear: This is not something that should have happened and, should we ever conduct a tournament like this again, will ever happen again.” Another official told the press that the NCAA had intended for the women to have access to a full weight room in the third round of the tournament. The men, for their part, have had access to one all along.

The gender inequality in college sports runs far deeper than a few social-media posts can reveal. As Cheryl Cooky, a professor studying sport sociology at Purdue University, told me in a recent phone conversation: “The problem is not the weight room itself, but what kind of groundwork has been laid that produced this moment where the weight-room controversy occurred. Nobody looked at that space and said, ‘Something’s not right here.’ It took someone posting on social media to bring attention to the issue.”

Although the NCAA is a nonprofit that organizes athletic tournaments for college athletes, it acts more like a professional-sports organization. And the deeply entrenched sexism in intercollegiate sports means that male athletes are treated with red-carpet fanfare, and women are treated as second-class citizens. That swag-bag gear, for instance? The women’s paraphernalia doesn’t say March Madness, because the NCAA refuses to use the name of its highly marketable men’s tournament to refer to the parallel women’s tournament, which is held at the same time. If you download the NCAA March Madness Live app, you might be under the impression that the women’s tournament doesn’t exist at all—no women’s schedule, bracket, or game highlights are available. This is the first year in which the entirety of the women’s tournament will be shown on national television, whereas the men’s tournament has been taking over airwaves for decades. And still, Sunday’s women’s championship game will be available only on ESPN, while the men’s championship game will air on CBS, a national broadcast network, making their game more widely available.

Broadcast and advertising deals are private-market decisions. But these issues involve student athletes, who are playing for schools beholden to Title IX—the statute that prohibits gender inequality at any educational institution receiving federal financial assistance (basically every school in the NCAA, via student financial aid). So is it legal that the NCAA calls its women’s tournament by a different (and far less marketable) name? Or that the broadcast deals it strikes for the men’s tournament are so much larger than those for the women’s? According to the Supreme Court’s decision in NCAA v. Smith, it is.

In 1999, the Court ruled that, although the NCAA runs sports tournaments for schools—and collects money from those schools—the league itself does not receive direct funds from the federal government. But Neena Chaudhry, the general counsel and senior adviser for education at the National Women’s Law Center, says a legal argument could be made that the NCAA should be held to Title IX when it comes to these tournaments. Chaudhry, who worked on NCAA v. Smith, has successfully argued at the state level that high schools have essentially given sports leagues controlling authority over their federally funded athletic programs. “Because schools need athletic associations to schedule championships, to run them, and … this is not something schools can do themselves,” she told me, “the athletic association has to be subject to Title IX.”

The current attention on the differences between the men’s and women’s college-basketball tournaments may be just the shove needed to force an NCAA–Title IX reckoning. The day after Prince’s video was posted, for instance, Suzette McQueen, the chair of the NCAA Committee on Women’s Athletics, wrote a letter to Emmert asking for an investigation into how the weight-room inequity occurred. McQueen noted that the incident “undermined the NCAA’s authority as a proponent and guarantor of Title IX protections.” Under the current law, the NCAA has no requirement to abide by Title IX, but McQueen’s language certainly reveals that the organization is concerned about at least appearing as though it does.

On March 24, federal lawmakers raised a similar argument. According to a letter obtained by The Washington Post, a group of 36 House Democrats wrote to Emmert to ask for a review into “all other championship competitions to ensure that they adhere to the gender equity principles of Title IX.” The next day, Emmert announced that the NCAA had retained a law firm to conduct an external gender-equity review of all three championships in all three divisions. In response, the Women’s Basketball Coaches Association said that the review needs to go even further.

“There’s no question that women are discriminated against by NCAA,” Ellen Staurowsky, a sports-media professor at Ithaca College, told me by phone. She pointed to the NCAA’s success at elevating the annual men’s basketball tournament to can’t-miss-TV status and securing more than $1 billion a year in broadcast and advertising rights for it alone. The women’s tournament, which was taken over by the NCAA in 1982, brings in just $35 million a year in broadcast rights, or approximately 3 percent of the men’s tournament’s figures. “That percentage hasn’t changed in 30 years,” Staurowsky said. “And for an entity that … has built its enterprise on media, this discrepancy is intentional.”

Chaudhry said you don’t have to be an expert to see the promotional differences that exist. “At the college level, we see men’s teams get glossy media guides, and they might have sports-promotion personnel to promote their teams, or get more of the cheerleaders and band support,” she said. “And then there’s the question of media coverage and whether the school is working to try to get the same media coverage and exposure for men’s and women’s teams. Schools can’t just say it’s all about market forces; they need to look at what they’re doing … because Title IX covers publicity and promotion.”

The NCAA, which touts “fairness,” claims that the budget differences for the tournaments—and the fact that schools receive revenue from the league for the men’s teams they send to the tournament, but not for the women’s teams—are because the women’s tournament isn’t profitable and has fewer fans. The assertion that the women’s side isn’t as marketable is questionable, considering that eight of the top 10 college-basketball players with the biggest social-media followings are women. Some experts also question the financials. One analyst who testified in an ongoing NCAA antitrust lawsuit and had access to NCAA financial documents estimated that NCAA Division 1 women’s basketball generated $1 billion in revenue during its 2018–19 season. (The league does not publicly release its financial documents, though it recently said the 2019 women’s tournament lost $2.8 million. The NCAA did not respond to my requests for comment.)

Even if the NCAA is not held to the same Title IX laws, colleges and universities are. And Staurowsky argues that these individual schools, which play a part in selling the media rights to their teams’ regular-season games, are probably driving down the rates for women’s basketball broadcast deals by not selling them as a product on a par with those of their men’s teams. So when the NCAA goes to make the tournament deals, the women’s teams don’t get bigger offers, in part because of the lack of regular-season promotion by the schools themselves.

Whoever is to blame, March Madness—or, excuse me, the NCAA women’s basketball tournament and March Madness—offers a real opportunity for institutions to change, because it’s a rare time when a college sport has a men’s and women’s tournament at the same time. Change is possible, as evidenced by the popularity of March Madness itself. In the 1980s, you had to be a hard-core fan to even watch the men’s tournament, Cooky, the Purdue sports professor, told me. “It’s been an effort and investment in building the men’s tournament as a cultural Super Bowl–like event, so that even people who don’t watch sports or basketball usually are filling out brackets and following the tournament.”

That kind of exposure at the college level could make a difference for women’s sports platforms, broadcast deals, marketing opportunities, and television coverage at all levels. Chaudhry said it’s about time the NCAA’s promotional disparities are spotlighted. After all, since she successfully argued the aforementioned Title IX case in Michigan, the state athletic association there now has to support and promote its high-school girls’ sports tournaments the same way it does for the boys’. If the same law can’t apply to college athletes because of some NCAA loophole, then Title IX is merely providing lip service to gender equality, and nothing more.