A 50-Year Protest for Good Writing

A crisis of quality in literary criticism led Robert Silvers to found The New York Review of Books—and he believes the crisis continues today, online.

By Heart is a series in which authors share and discuss their all-time favorite passages in literature. See entries from Claire Messud, Jonathan Franzen, Amy Tan, Khaled Hosseini, and more.

It’s hard to remember that The New York Review of Books was once a young upstart. Since its very first issue in February, 1963—Susan Sontag, Gore Vidal, and W. H. Auden were among many all-star contributors—the magazine has been a revered venue for essays, book reviews, and political reportage. Still, Robert Silvers, the paper’s legendary founding editor, told me that the Review’s success was never a sure thing—it took an essay by Elizabeth Hardwick, and a citywide newspaper strike, to create a once-in-a-generation opportunity. In our conversation for this series, Silvers discussed his vision for the paper, the importance of editorial freedom, and the central place of book reviews within our broader culture of ideas.

Silvers—who, at 84, has been co-editor or editor for every issue of the Review—is the protagonist of The 50 Year Argument, a new documentary directed by Martin Scorsese and David Tedeschi. The film explores the magazine’s history and influence by splicing together interviews, archival footage, and scenes from a staged reading of classic Review pieces—including Darryl Pinckney on James Baldwin and Joan Didion on the Central Park Five. This loose structure mimics the pleasure of reading a magazine front to back, with wide-ranging stories and distinct voices that share borders as pages turn.

Robert Silvers, who co-founded the Review with Barbara Epstein, spoke to me by phone and email. The 50 Year Argument is now playing on HBO and HBO Go.

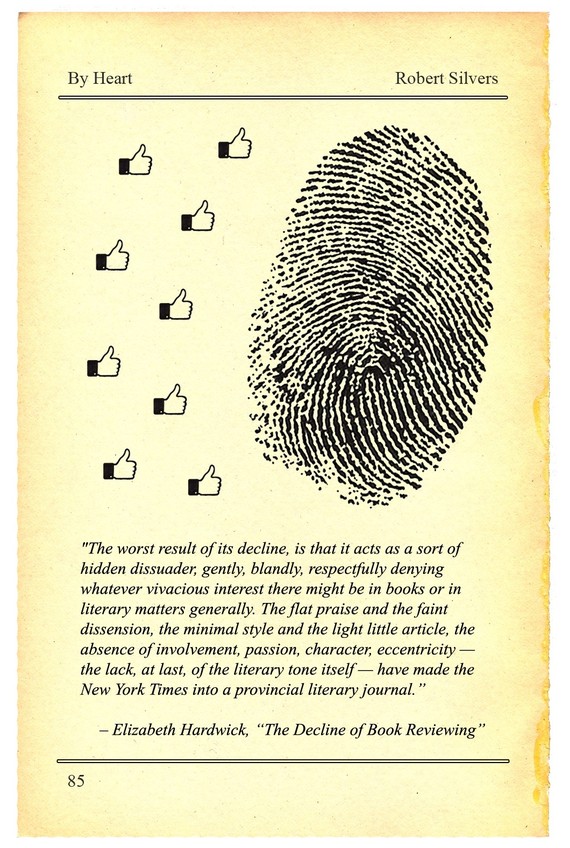

Robert Silvers: I think often of words from Elizabeth Hardwick’s article “The Decline of Book Reviewing,” which appeared in October, 1959, in a special issue of Harper’s I edited called “Writing in America.” In the passage that follows, Elizabeth is referring to the New York Times Book Review of those days—and what she said should not be applied to the paper under different editors in subsequent years:

“The worst result of the decline of the Times,” she wrote,

is that it acts as a sort of hidden dissuader, gently, blandly, respectfully denying whatever vivacious interest there might be in books or in literary matters generally. The flat praise and the faint dissension, the minimal style and the light little article, the absence of involvement, passion, character, eccentricity—the lack, at last, of the literary tone itself—have made The New York Times into a provincial literary journal.

I asked Lizzie to write the article because I’d been following her work for years in the Partisan Review, where she wrote scintillating reviews on everything from Saul Bellow to the current state of American culture. The wife of Robert (“Cal”) Lowell, she was a fiercely independent and beautifully elegant writer, and she defined the problem with her characteristic sharpness. “The drama of the book world is being slowly, painlessly killed,” she wrote, by “slumberous acceptance.” New books were being “born into a puddle of treacle” and “the brine of hostile criticism is only a memory.” For Lizzie the current reviewing seemed lacking in anything exciting or daring or challenging or troubling, or in some way provoking.

Her article caused a great deal of controversy and elicited an objection from the New York Times. It was embarrassing for Harper’s, because the magazine was owned by Harper and Row—a book publishing company that was very concerned about its book reviews in the New York Times! The publisher of Harper and Row felt he had to attack her in the next issue; and she replied, not giving an inch. Her essay helped cement the sense many of us had that something better was needed. “Nothing matters more,” she wrote, “than the kind of thing the editor would like if he could have his wish. Editorial wishes always partly come true.”

So Lizzie’s words were very much on my mind in the winter of 1963, during the long New York Times newspaper strike, when Jason Epstein, a good friend who was then editorial director at Random House, called me at my office and asked if I would be willing to leave Harper’s to edit a new book review.

It entirely came out of the blue. Jason had had dinner the night before with Lizzie and Cal and his wife Barbara, who was a great friend of mine. And the thought came up that the different sort of journal Lizzie thought was needed might now be possible. Jason perceived that the time had come when you could start a new paper without a penny, because the publishers were going crazy. Their books were inexorably coming from the presses, long ago contracted for. But there were no reviews in the principal place that wrote about books and encouraged people to buy them—namely, The New York Times Book Review.

Therefore, if a new publication with a plausible list of contributors and a plausible appearance came out, publishers would almost have to advertise in it. They had a flow of books that needed some attention, somewhere. Within an hour I called Barbara, and told her I hoped she’d join with me as co-editor. When I told Jack Fisher, the editor of Harper’s, that I thought I should take a leave to start a new paper, he said, “Great! You’ll learn a lot and be back in a month.” Then Barbara and Lizzie and I went to the darkened Harper’s offices at night and went through the stacks of books, and we sent a number of them to some of the writers we knew and admired most: W.H. Auden, Mary McCarthy, Norman Mailer, Bill Styron, Alfred Kazin, Susan Sontag, and Gore Vidal, to name only a few. We asked for three thousand words in three weeks in order to show what a book review should be, and practically everyone came through. No one mentioned money. Barbara and I made a layout listing some names on the first page and went around with it to publishers and agencies—and most took an ad, enough for us to pay the printer we found in Bridgeport, Connecticut—when the paper appeared within a month.

We had 100,000 printed copies sent out—to college bookstores and newsstands in New York, where they sold out very quickly. Our first issue opened with the only editorial we ever published. The New York Review of Books, we wrote, did not

seek merely to fill the gap created by the printers’ strike in New York City but to take the opportunity which the strike has presented to publish the sort of literary journal which the editors and contributors feel is needed in America. This issue of The New York Review of Books does not pretend to cover all the books of the season or even all the important ones. Neither time nor space, however, have been spent on books which are trivial in their intentions or venal in their effects, except occasionally to reduce a temporarily inflated reputation or to call attention to a fraud. The contributors have supplied their reviews to this issue on short notice and without the expectation of payment: the editors have volunteered their time and, since the project was undertaken entirely without capital, the publishers, through the purchase of advertising, have made it possible to pay the printer. The hope of the editors is to suggest, however imperfectly, some of the qualities which a responsible literary journal should have and to discover whether there is, in America, not only the need for such a review but the demand for one. Readers are invited to submit their comments to The New York Review of Books, 33 West 67th Street, New York City.

That was Barbara and Jason’s address. And we got nearly a thousand letters. We had them in big boxes. That was crucial because, when we tried to raise money from a very small group of friends a few months later, we could show them evidence that people wanted us to go on.

If there had been no strike, there would have been no Review. The advertising agencies and publishers would have told us: “Sorry, we’ve already spent our budgets on the New York Times and the New York Herald Tribune.”

After the strike we put out a second issue to show the Review was not a one-shot affair and it featured an interview with Edmund Wilson with himself. “Every Man His Own Eckermann” he called it, referring to the interviewer of the aging Goethe. In it he wrote for the first time I know of about the many different artists he admired—Dürer, Goya, Degas, George Grosz, Edward Gorey, and above all the neglected French caricaturist Sem. He was “astringent,” Wilson said, but in his work you found “a tumult of movement.” We set about raising money to publish a regular paper that autumn. Whitney Ellsworth of The Atlantic had joined us as publisher, and we went to see Brooke Astor, whom we found reading the paper. “I like it,” she said, “and I’ll invest in it with my own money.”

What were we looking for? Of course we wanted to publish the work of the writers we admired for an audience that would appreciate them. But it seems too simple, too glib to say that we hoped for clear and poised and brilliant writing that would challenge their thinking. Of course we did. But what matters is a particular insight and how it is put. In our first issue Mary McCarthy wrote about William Burroughs’s Naked Lunch, and in a way we had not seen before. Between Burroughs and Jonathan Swift, she wrote,

there are many points of comparison; not only the obsession with excrement and the horror of female genitalia but a disgust with politics and the whole body politic. Like Swift, Burroughs has irritable nerves and something of the crafty temperament of the inventor. There is a great deal of Laputa in the countries Burroughs calls Interzone and Freeland, and Swift’s solution for the Irish problem would appeal to the American’s dry logic....

Yet what saves The Naked Lunch is not a literary ancestor but humor. Burroughs’ humor is peculiarly American, at once broad and sly. It is the humor of a comedian, a vaudeville performer playing in One, in front of the asbestos curtain to some Keith Circuit or Pantages house long since converted to movies. The same jokes reappear, slightly refurbished, to suit the circumstances, the way a vaudeville artist used to change Yonkers to Trenton when he was playing Seattle.

We hoped for writers who could put across ideas that are not widely expressed, including skeptical criticism of the language of convention. It seemed obvious that one function of an independent paper is to challenge authority. There is an enormous imposing and dominant presence in all our lives of the official way of doing things, the approved way, the successful way, and they deserve scrutiny. Barbara and I soon saw that there were books on practically every subject, and that there was no subject we couldn’t deal with. And if there was no book, we would deal with it anyway. We tried hard to avoid books that were simply competent rehearsals of familiar subjects, and we hoped to find books that would establish something fresh, something original. And we had a kind of pact that in reviewing books we would try to avoid dead language, particularly the tired metaphors we saw around us as a kind of curse. So in our fifty years, you won’t have seen in our pages the figurative uses of “context,” or “massive,” or the phrase “in terms of,” unless there are clear terms, or “framework,” unless there is an actual frame, or anything “on the table” or “off the table,” unless there is a table.

The central fact was and is that we could publish anything we wanted as long as we could pay the printer. If there wasn’t a book on a subject we wanted to deal with, we would find someone to write about it anyway. Our thought was: so what? We’ll publish poetry and opera reviews and essays on particle physics and computer programming—whatever we think is interesting.

This freedom of expression—to cover the topics we wanted the way we wanted—was made possible because Jason set up the paper in a brilliant way. The friends and people we knew who put up money had what Jason called “B” shares—which gave them the right to financial benefits if there were any. Then there were the A shares, owned by just the Lowells, the Epsteins, Whitney, and myself. We had the power to appoint the editor and determine the content of the paper. We could do whatever we wanted as long as we could pay the printer and our writers, none of whom were paid members of the staff. We paid for each article separately. No one had any authority over us, and when Rea Hederman joined us as publisher in the mid-1980s he improved everything about the paper’s circulation and business, and he set up the admirable publishing venture called New York Review Books. But he did so with the understanding we’d have exactly the same editorial freedom, and we’ve had it.

I can’t think of any other paper where the editors are in absolute control of the content—and that means of course we’ve had no excuses. We expected that many people would dislike what we were doing; we published work that took early critical positions on the Kennedy administration, the Johnson administration, and Fidel Castro’s regime, Mao’s Peoples Republic, and many right-wing regimes, and our writers opposed America’s Vietnam war and the Iraq war. We published American dissident writers such as Noam Chomsky and I.F. Stone and many articles by Russian and Eastern European dissident writers such as Andrei Sakharov, Adam Michnik, and Vaclav Havel, who wrote some 27 pieces for us, some before and after he was sentenced to prison, some after he became president of the Czech Republic.

We knew that editors and writers in other places were being set upon, bullied, restricted, whether in China or Pinochet’s Chile and it was a natural obligation for us to publish protests against their treatment. And we soon learned that when people we defended as victims came to power, they too could sometimes exercise severe repression. When we published an article about the brutality of the victorious North Vietnamese regime, dozens of people cancelled their subscriptions. They could, it seems, only conceive of the North Vietnamese as victims.

We’ve been lucky from the first in that some of the most brilliant writers we know were willing to write about political events for us. Mary McCarthy went to Vietnam for the Review, Joan Didion went for us to San Salvador when it was dangerous just to walk down the street; and she wrote a remarkable article arguing that the press and the public were accepting questionable charges against the young men accused of attacking the Central Park jogger. They were later found innocent. Susan Sontag wrote for us from Sarajevo when the city was under bombardment and one of our writers has just driven through Syria by car for an article for us.

Yet how very aware we are of what needs more attention. Sue Halpern has written brilliantly for us on the social and cultural effects of the computerized world, particularly on the intrusive surveillance by governments and computer companies. All around us there are many, many thousands of web sites and blogs and twitters that have become the influential sources of the information pervading the internet; yet in contrast to kinds of scrutiny that emerged during the Gutenberg era, there is hardly any serious critical consideration—in Elizabeth Hardwick’s sense—of the quality of what we are seeing on our computers—a huge and perplexing challenge for the future of criticism.

Do articles and book reviews have a calculable political and social impact? Frankly, it is simply a mystery whether anything you publish will get attention and change someone’s mind. When Mark Danner was able to obtain the secret International Red Cross report describing the torture of prisoners by the Bush administration, and we published his article about it, suddenly it was talked about by government officials and publications and television commentators. Because it came from the Red Cross, it had a legitimacy that challenged the denials of the Bush White House. But on the whole, publishing political and cultural criticism is a kind of roulette game: You put something out and you have no clue what its effect will be. You mustn’t think too much about influence—if you find something interesting yourself, that should be enough.

I’m always looking for the next piece of writing that is going to change my view of some aspect of the world; something that will put forward a fresh and clarifying new idea that I had never encountered before. Discovering such an article can be one of life’s most exciting moments.