Dear Therapist: My Girlfriend Had an Affair With My Co-worker

I’ve forgiven her, but I can’t forgive him.

Don't want to miss a single column? Sign up to get "Dear Therapist" in your inbox.

Dear Therapist,

Five months ago, my long-term girlfriend cheated on me. Our relationship had broken down due to poor communication, working too much, resentment, etc. While I was the one cheated on, I now fully acknowledge the part we both played, and after a period of acute anger, I came to the conclusion that I still love my girlfriend, and that I was as angry at the infidelity as at the fact that we had let the relationship get as low as it did. She also expressed deep regret, sorrow, and self-loathing for her actions. We had several long heart-to-heart conversations over the following weeks, and those conversations taught me new things about her. The process of repair is ongoing, but since the affair, we have been closer than we’d been in a long time.

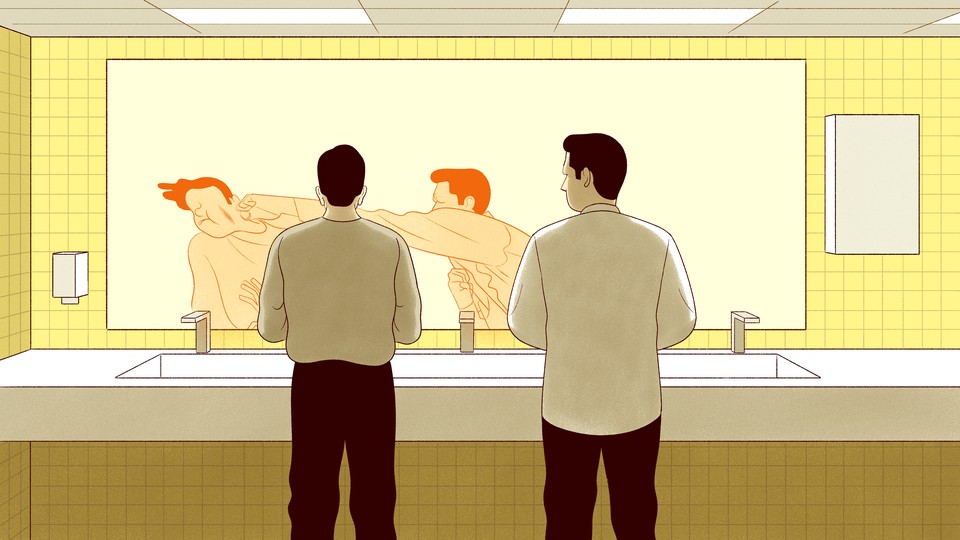

My real issue is this: The person she cheated with is a co-worker of mine. We are in the same (large) department, and I still see him often in the common areas. I haven’t talked to him since this happened, and I have no desire to communicate with him. In fact, just seeing him has a visceral effect on me. My breathing increases; my heart races. I have a strong urge to punch and break things to get this “fight response” out of my system. The passage of time hasn’t lessened this feeling, and it completely disrupts me, sometimes souring my mood for the day. I don’t want him to have this effect on me or to have my day disrupted like this.

I have talked about this with my girlfriend, but I don’t want to keep doing that. It makes her feel terribly guilty and sad, and while she wants to help, she doesn’t know how. Neither do I. What should I do?

Chris

Dear Chris,

First, you should know that your reaction is completely understandable in the aftermath of infidelity. In fact, what you’re describing is a common response to trauma. I use the word trauma because while most people can easily imagine (or are personally acquainted with) the pain of being cheated on, what some may not realize is that many betrayed partners experience symptoms of PTSD.

Some of these symptoms are irritability, insomnia, hypervigilance, and difficulty concentrating. People can also suffer from “intrusion symptoms,” such as flashbacks (of, say, walking in on a cheating partner), nightmares related to the affair, physical reactivity to traumatic reminders (like increased heart rate when running into the co-worker), or emotional distress in the face of traumatic reminders (like the mood “disruption” you’re experiencing when seeing him).

The “real issue” here is that the affair was very painful, and seeing your co-worker is a traumatic trigger for the actual issue: betrayal. Part of what makes infidelity so devastating is that it involves multiple levels of betrayal. Yes, your girlfriend betrayed your trust, and the two of you are working through that together. But your co-worker also betrayed you, and this part of the trauma can be especially hard to work through, because most people focus so much on the primary betrayal (between you and your girlfriend) that they don’t take the time to work through—or even acknowledge—the secondary one.

You may be thinking, Wait, I barely know this co-worker. It’s not as if he was my best friend. And to be sure, many would likely say that this isn’t about the other person at all. After all, this person never made a commitment to you. Only your partner did.

But there’s something disingenuous about that line of thinking. The other person involved in infidelity, even if that person is single and available and has little or no connection to the betrayed partner, is complicit in the betrayal. Rationalizations such as “She was unhappy in her relationship—I didn’t do anything wrong” are the equivalent of driving the getaway car in a robbery and claiming not to be an accessory to the crime. “I wasn’t in a relationship with you—she was” is tantamount to saying, “I didn’t commit the theft; I just happily took a share of the stolen money.” These mental gymnastics leave the betrayed partner feeling irrational for having reactions like the one you’re having when seeing your co-worker.

Presumably, your co-worker knew that the woman he was having sex with was your girlfriend. So in addition to the pain of seeing him at work, there’s also the awkwardness of neither of you acknowledging the betrayal. He hasn’t come up to you and said, “I’m sincerely sorry about the pain I caused.” Of course, it’s possible that he hopes you don’t know about it; or that he knows that you do, and he feels too guilty to bring it up.

I understand your desire not to talk to this co-worker, but here’s the problem: Unacknowledged trauma is like a double dose of trauma; trauma needs air, and if you can take the initiative to give it some, you’ll breathe more easily too.

You might find a moment to take your co-worker aside and say something like, “It’s been really awkward for me to see you at work after what happened between you and my girlfriend, and for both of us to pretend it didn’t happen. I wonder if you’ve felt just as awkward and wanted to say something to me. I’m not interested in details or anything like that—I believe everything my girlfriend has told me and we’re doing much better now. All I want to say is that your part in what happened hurt me deeply, and I thought you should know.” Then stop talking and let him fill in that space however he chooses—even if you have to wait through an excruciatingly long pause.

It doesn’t matter what he says—all that matters is that you did something helpful for yourself: You spoke the unspeakable that was floating between you like noxious fumes. I can’t emphasize enough the value of speaking the unspeakable. Well-meaning friends might give you advice along the lines of, “Forget about him. He’s dead to you!” Except that he’s not. The people who hurt us are never dead to us; even worse, they haunt us if we let them.

I’m not suggesting that after approaching your co-worker, you won’t still find running into him upsetting. But like an effective pressure valve, speaking the unspeakable to him will help to release some of the tension. Remember, too, that in the life cycle of trauma, five months isn’t long at all, and it sounds like you and your girlfriend have had a lot of important conversations in that time. This speaks to the strength of your relationship, and freeing up some emotional real estate by giving less of it to your co-worker will only help you and your girlfriend continue to move forward together.

Dear Therapist is for informational purposes only, does not constitute medical advice, and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician, mental-health professional, or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. By submitting a letter, you are agreeing to let The Atlantic use it—in part or in full—and we may edit it for length and/or clarity.