If we as a society are allowed to do a variety of dangerous things (bungee jumping, skydiving, drinking), why does drug use cross the line?

ejwhite/Shutterstock

In the Preamble to the 1971 Report of the White House Conference on Youth (which I mentioned in my first post), the nearly 1,500 conference delegates reaffirmed the importance of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. They also added a few other "crucial" amendments, outlining rights that would "be meaningful to all persons in our society." Those rights included:

- The right to adequate food, clothing, and a decent home.

- The right of the individual to do her/his thing, so long as it does not interfere with the rights of another.

- The right to preserve and cultivate ethnic and cultural heritages.

- The right to do whatever is necessary to preserve these rights.

Like the other focuses of the conference, such as the draft, education, unemployment, and environmentalism, these rights spoke clearly to the delegates' desire to live peacefully and prosperously in their natural and political terrain. In the realm of drug use, however, one of these rights stands out from the rest: the 'right of the individual to do her/his thing.' As long as no one gets hurt or has their own rights trampled upon, the delegates argued, why does an individual's choice to smoke pot or shoot heroin necessitate regulation (or punishment) from the federal government? In other words, why do basic personal rights collapse as soon as imbibed chemicals are involved?

- Where and What Is Pottersville?

- Johnnie Carson on "African (Drug) Issues"

- Big Questions, Free Will, and Addiction

In the debate over the root causes of drug use, particularly over the question of whether it is a personal choice, the issues of personal and societal rights frames the discussion completely. Drug use (or nonuse) may be a choice, a right, or even a function of a free-market, capitalist economy. The questions that the conference delegates bring up are sound: Do we have a right to unimpeded personal conduct (including the right to alter our consciousness) so long as no one else is being harmed? Or is the personal harm caused by drug use sufficient for federal prohibition? If we as a society are allowed to do a variety of other dangerous things (bungee jumping, skydiving, and consuming legal liquor and cigarettes, for instance), why does drug use cross the line between a 'personal right' and a 'societal danger'? And, really, what causes more harm: drug use itself, or the prohibitionist war on drugs?

Defendants of the personal right to use drugs come from both the left and right of the political spectrum. On the left, one finds the delegates of the Youth Conference, who argue that the right of every person to harmlessly do 'her/his thing' is a core component of the American tenet of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. The ACLU, for instance, endorses the personal right to consume drugs. Former director Ira Glasser noted in 2000 that "the ACLU's position is basically that criminal prohibition is inappropriate in matters that involve a person's own behavior." And the flourishing medical marijuana movement regularly asserts the rights of its patients to live a healthy, pain-free life, even if that means consuming a substance that is currently considered to have "no medical use" for treatment in the United States.

The idea that drug use was essentially a civil right had particular resonance in the 1960s and 1970s, as several movements broke down barriers of governmental prohibition on personal conduct. The civil rights, gay rights, and feminist movements battled to give certain citizens the rights they deserved but had long been denied. In Loving vs. Virginia (1967), the Supreme Court ruled that banning interracial marriage was unconstitutional. In Roe vs. Wade (1973), women were given increased control over their own reproductive systems. That this thinking would extend to the rights of individuals to consume what they please was, according to the Youth Conference delegates, a natural line of thought. And this right was worth preserving, they argued, so long as no one else got hurt, an argument used to support many of the other civil rights advancements of the time as well.

The right to consume drugs wasn't monopolized by the left, however. Others, particularly libertarian psychiatrist Thomas Szasz and renowned neoliberal economist Milton Friedman, have supported rights-driven drug use by citing the free market to support their claims. Aren't drugs commodities like anything else, they argue, and, if harm reduction is the goal, shouldn't drugs then be available to purchase safely and legally in a consumer-driven marketplace? Szasz, echoing the Tea Party today, made his argument a matter of American ideals: "I favor free trade in drugs for the same reason the Founding Fathers favored free trade in ideas: in a free society it is none of the government's business what ideas a man puts in his head; likewise, it should be none of its business what drugs he puts into his body."

The right to consume drugs wasn't monopolized by the left, however. Others, particularly libertarian psychiatrist Thomas Szasz and renowned neoliberal economist Milton Friedman, have supported rights-driven drug use by citing the free market to support their claims. Aren't drugs commodities like anything else, they argue, and, if harm reduction is the goal, shouldn't drugs then be available to purchase safely and legally in a consumer-driven marketplace? Szasz, echoing the Tea Party today, made his argument a matter of American ideals: "I favor free trade in drugs for the same reason the Founding Fathers favored free trade in ideas: in a free society it is none of the government's business what ideas a man puts in his head; likewise, it should be none of its business what drugs he puts into his body."

But it was precisely this rights-based argument that generated some rather virulent opposition to drug use. Returning to President Richard Nixon, who effectively linked drug use to crime in the popular mind, drug use was no harmless personal choice or a function of capitalism: it was pure danger for both the user and the society in which he lived. In a 1968 speech he gave in Anaheim, California, Nixon stated that, "I believe in civil rights, but the first civil right of every American is to be free from violence, and we are going to have an administration that restores that right in the U.S. of A." By reframing drug use as less a threat to the user and more a risk to innocent others who, because of drug use, would be put in harm's way, Nixon argued that a nation which allowed drug use was the diametric opposite of a nation where citizens lived free from violence and fear.

The Parents' Movement also picked up on this claim. The commercialized drug culture, which activists feared was teaching their adolescents that drug use was acceptable and cool, was full of irresponsible adults who "distorted and twisted the fundamental and noble conception of civil rights into the 'personal right' to illegally use mind-altering drugs." This 'personal right to drugs' was a bastardization of righteous concepts, activists like Keith Schuchard proclaimed, and couldn't be placed in the same conversation with the actions of people like Martin Luther King, Jr.

Former drug czar William Bennett saw Nixon's incarceration bid and raised him mandatory minimum sentences. Bennett stated that the purpose of jailing drug addicts and dealers was to "exact a price for transgressing the rights of others," an argument that again reframed drug use not as an act of personal choice or volition, but as a dangerous action that impinged upon the rights of non-users. Similarly, Los Angeles Police Chief Daryl Gates (founder of DARE) said that casual drug users "should be taken out and shot," while First Lady Nancy Reagan stated that any user of illicit drugs was an "accomplice to murder." Ultimately, these individuals' claims came down to the idea that drug use is not simply a benign personal act or a form of participation in a free-market economy: it can involve supporting dangerous systems of trafficking and cartels, all of which imperil the innocent society in which the drug consumer lives.

Former drug czar William Bennett saw Nixon's incarceration bid and raised him mandatory minimum sentences. Bennett stated that the purpose of jailing drug addicts and dealers was to "exact a price for transgressing the rights of others," an argument that again reframed drug use not as an act of personal choice or volition, but as a dangerous action that impinged upon the rights of non-users. Similarly, Los Angeles Police Chief Daryl Gates (founder of DARE) said that casual drug users "should be taken out and shot," while First Lady Nancy Reagan stated that any user of illicit drugs was an "accomplice to murder." Ultimately, these individuals' claims came down to the idea that drug use is not simply a benign personal act or a form of participation in a free-market economy: it can involve supporting dangerous systems of trafficking and cartels, all of which imperil the innocent society in which the drug consumer lives.

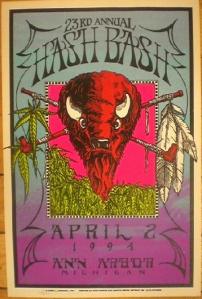

What's at stake in this debate is the age-old question of where my rights end and yours begin. After all, my right to swing my arm ends at the tip of your nose, and seemingly innocent acts may not be so innocuous once we know of their effects. So, does this mean casual drug use is an act of civil disobedience, as it is framed at the University of Michigan's annual Hash Bash? Or is it part of a larger, and much scarier, system that trounces individual liberty and promotes violence? Like determining whether drug use is caused by root causes or personal culpability, this debate gets at the very heart of the war on drugs. Since it propels so much of our drug legislation, it needs to be considered when framing social policy.

(For those who want to know more, our old friend Wikipedia actually has an excellent summarization of arguments for and against drug prohibition. You can also check out some really great books.)

This article originally appeared on Points, an Atlantic partner site.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.