The Cyber Activists Who Want to Shut Down ISIS

Somewhere in Europe, a man who goes by the name “Mikro” spends his days and nights targeting Islamic State supporters on Twitter.

In August 2014, a Twitter account affiliated with Anonymous, the hacker-crusader collective, declared “full-scale cyber war” against ISIS: “Welcome to Operation Ice #ISIS, where #Anonymous will do it’s [sic] part in combating #ISIS’s influence in social media and shut them down.”

In July, I traveled to a gloomy European capital city to meet one of the “cyber warriors” behind this operation. Online, he goes by the pseudonym Mikro. He is vigilant, bordering on paranoid, about hiding his actual identity, on account of all the death threats he has received. But a few months after I initiated a relationship with him on Twitter, Mikro allowed me to visit him in the apartment he shares with his girlfriend and two Rottweilers. He works alone from his chaotic living room, using an old, battered computer—not the state-of-the-art setup I had envisaged. On an average day, he told me, he spends up to 16 hours fixed to his sofa. He starts around noon, just after he wakes up, and works late into the night and early morning.

No state intelligence agency assigned Mikro this work. He answers to no one and uses methods that are not only ethically ambiguous, but also beyond any kind of democratic oversight and accountability. Nobody even knows what he’s doing except for his girlfriend and a motley crew of dedicated operatives. His neighbors just think he’s a recluse. To his friends, he’s a computer nerd.

Unbeknownst to any of them, Mikro is the “operations officer” for GhostSec, a group with the self-declared mission of targeting “Islamic extremist content” from “websites, blogs, videos, and social media accounts,” using both “official channels” and “digital weapons.” The group claims to have disrupted or taken down more than 130 ISIS-linked websites by overwhelming their servers with fake traffic from multiple sources. (This is called a Distributed Denial of Service, or DDOS, attack.)

More spectacularly, GhostSec also claims to have thwarted a July 2015 jihadist attack on a Tunisian market by passing information to a private security company called Kronos Advisory, which then gave it to the FBI. Michael S. Smith II, one of Kronos’s founders, confirmed this over the phone. He made sure to add that GhostSec is “not working for me or with me per se. … We are collaborating in gathering and presenting information that is valuable to counterterrorism officials.”

Mikro said he played a leading role in uncovering the plot. “I was told by one of my hunters, ‘Look into this.’ And from there we built up the case.” He also showed me a set of screenshots from the dark web listing ISIS donation pages that, he said, were taken down shortly after GhostSec had identified them. He was deliberately vague about how the group came across these pages, why and when they were taken down, and what his role as “operations officer” actually involves.

In February, Mikro founded a second group called CtrlSec. It’s closely related to GhostSec; both groups originate from Anonymous, and they share personnel and resources. But Mikro told me CtrlSec is no longer affiliated with Anonymous, a non-hierarchical organization that prohibits its members from soliciting financial support from outsiders. “We have a structure,” Mikro explained. “We have a leadership, we have roles, and we need money.”

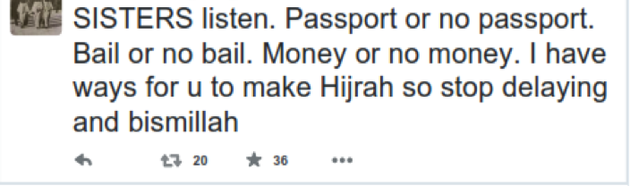

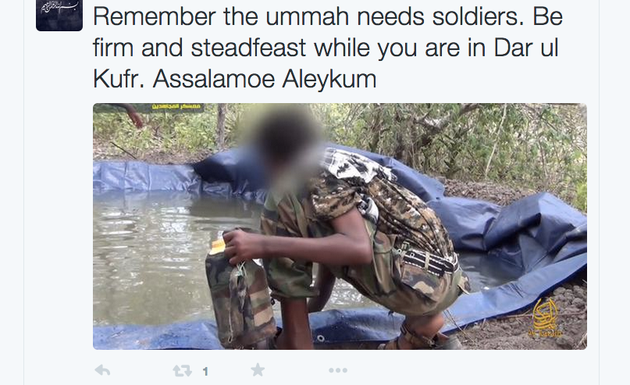

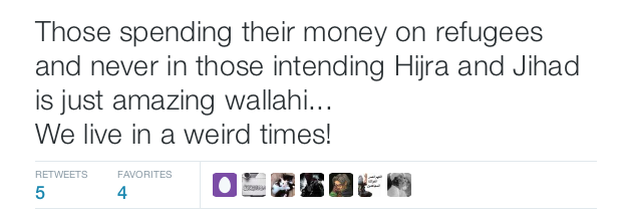

CtrlSec’s sole mission is to eliminate pro-ISIS accounts on Twitter. A study by the Brookings Institution fellow J.M. Berger and the data scientist Jonathon Morgan found that in the last four months of 2014, at least 46,000 Twitter accounts were used by ISIS supporters, potentially reaching an audience of millions. They also found that ISIS-supporting accounts had an average of about 1,000 followers each and that ISIS supporters on Twitter were far more active than ordinary Twitter users.

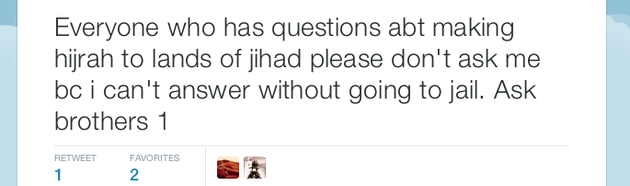

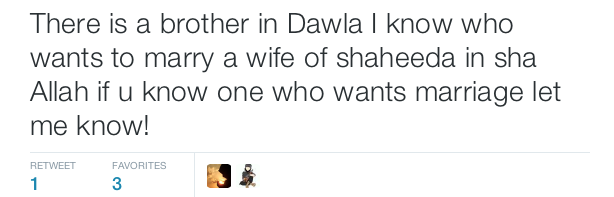

Mikro evaded questions about CtrlSec’s methods in the same way he evaded logistical questions about GhostSec. When I asked whether CtrlSec uses algorithms to identify pro-ISIS Twitter activity, he was adamant that it does not. Instead, he insisted, every suspect tweet and Twitter account is tracked down manually by one of the group’s 28 operatives, many of whom can read Arabic. I asked him what criteria these operatives use to determine pro-ISIS sympathies and he replied, “You need two eyes and brain.” When I probed him further, he said, “We are trained to see indicators. … Also, we monitor the well-known accounts to pick up new supporters.” Mikro claimed that CtrlSec identifies 200 to 600 pro-ISIS Twitter accounts a day.

Once the group is satisfied that it has identified a pro-ISIS account, it adds the account in question to its “blacklist,” which it tweets out in automated installments. The group then asks its followers to flag the blacklisted accounts for Twitter. (Under the company’s rules, users can be suspended if they “promote violence against others” or post “excessively violent media.”) “The purpose of this account is to expose ISIS and Al-Qaida members active on Twitter,” explains CtrlSec’s Tumblr page. “Whether they should be reported or not isn’t our decision: it’s your decision.”

It’s hard to predict just how much it would cripple ISIS if its promoters were banned from Twitter altogether. As The Atlantic’s Kathy Gilsinan has argued, ISIS’s capacity to mobilize unprecedented numbers of foreign fighters may have more to do with its real-world military successes than the doggedness of ISIS “fanboys” on Twitter. And suspended users frequently return to set up new Twitter accounts.

Still, Berger, one of the authors of the Brookings report, says there is “substantial evidence” that account suspensions seriously limit the group’s reach, given how effective Twitter is as an instrument for disseminating information to vast audiences across the globe. In Berger’s “6-Point Plan to Defeat ISIS in the Propaganda War,” co-authored with the Harvard terrorism scholar Jessica Stern, the sixth and last point is, “Aggressively suspend ISIS social-media accounts.” He and Stern conclude that “suspensions do limit the audience for ISIS’s gruesome propaganda.” Berger has also noted that even when banned pro-ISIS users resume their efforts under new usernames, they suffer from the negative “impact of time lost to the process of creating new accounts and waiting for followers to find them.”

Mikro claimed that since February, CtrlSec has helped remove 60,000 to 70,000 pro-ISIS Twitter accounts. These are astonishing numbers (and ones that top Berger and Morgan’s estimate of total pro-ISIS accounts). When I pressed Mikro on how he arrived at the figure, he wouldn’t elaborate. Early on, he said, he tried to share his blacklist directly with Twitter. “But they never got back to us,” he told me. This still exasperates him. “If they would cooperate with us, it wouldn’t take more than a couple of days to shut [ISIS] totally out. They are shutting down in waves,” he continued. “Suddenly 2,000 accounts are gone, 5,000 accounts are gone, and then [ISIS] can go two weeks with no suspensions, and then 10,000 accounts are gone.”

In March, Twitter suspended over 2,000 pro-ISIS accounts, earning one of its founders, Jack Dorsey, several death threats. However, Mikro believes it’s no coincidence that “every target they take down has been tweeted by us.” (I contacted Twitter to find out whether it has used CtrlSec’s lists to identify pro-ISIS accounts for suspension, but I have yet to receive a response.)

As I pressed Mikro on his modus operandi, he showed me a Twitter account that had just made it onto his blacklist. Its tweets contained a lot of ISIS insignia, and I could readily make out the distinctive logo of ISIS’s media arm, Al Hayat, in some of the screenshots. Many of the photos depicted the kinds of medieval atrocities that have become ISIS’s trademark.

He opened a folder containing a collection of ISIS atrocity porn. “This is what I have to deal with every day,” he said, clicking on scores of photos of beheadings and other highly stylized massacres. “I was looking at these over breakfast this morning.” One of the photos he showed me was of a child, around 8 or 9, dressed in military garb, holding a severed head. Another was of a head on a spike. I suddenly felt an urge to be elsewhere.

Then Mikro showed me an excruciatingly vivid photo of a severed human neck. It had been sent to his Twitter inbox by a self-professed ISIS supporter and addressed personally to him. There were no words attached, just the gut-wrenching gore. Mikro said he’d lost count of the death threats he’d received. “I don’t really take them seriously,” he said. Then he added, “I know it’s very real, but I can’t let it affect me, because I’m up to my neck in shit already with this. If they figure out who I am … they would do anything to come here and take me down.” He showed me, with not a little pride, a hit list posted online by ISIS supporters in which CtrlSec held first place.

Before he became a counter-jihadist, Mikro spent years trying to figure out exactly who he wanted to be. He was a boisterous and badly behaved child, always in trouble at school. He said his mother’s boyfriend disliked him and threatened to leave her if she didn’t put him in foster care. “I woke up one morning and I wanted to go out but noticed the front door was locked. So I asked, ‘What’s happening?’ And my mum told me I was going away for a couple of weeks. But when you’re told to pack everything you have, you start to smell that it’s more than a week.”

He said he “went crazy” and “started kicking down the door. I was going totally maniac and went into my room and started crushing everything. And then the child welfare came, and they actually called the police. And there came a guy with a helmet and shield in through the door, with a couple of police officers behind. They fucking handcuffed me and carried me out to the police vehicle and drove me off to the child-welfare office. I was 12 years old.” The “couple of weeks” away turned out to be six years.

Mikro insisted he doesn’t feel hostility toward his mother now. She was troubled, he explained, always blowing the rent money to feed her gambling habit. There’s clearly more to the story than this, but he was reluctant to say more about it. “I felt rejected,” he told me simply. “I still feel it. But I’ve learned to live with that.”

Initially, Mikro moved in with a Christian family, where “I was forced into believing in God.” After a year, he was placed with a Muslim family from Turkey and expected to follow the Islamic faith. He recalls being made to fast during Ramadan. “I used to walk to school instead of taking the bus and used the money to buy food because I was so fucking hungry.” He said he tried being a Muslim: “I actually found the Muslim belief much more calming than the Christian.” But now, he concluded, “Religion isn’t for me.”

Mikro’s placement with the Muslim family didn’t last long anyway. After he was caught using drugs, he was transferred to “a house in the middle of nowhere, with a bunch of troubled teenagers.” It was there that Mikro’s life changed forever. “I remember it really clearly because it has haunted me in every court I have been in.” The quarrel was over a girl who had been assaulted by one of the boys in the house. Mikro said he and two friends tried to confront the boy but were stopped by a group of care workers before they could exact revenge. “One of them … I’m not proud of it, because he was a really nice guy and he was just trying to make us think logically, when I look back at it. We dragged him to the ground and kicked him several times. He cracked, like, six ribs. He didn’t break it, but he did serious damage to his spine. He stopped working with youths after that. The doctor said that if we’d kicked him one more time in the chest, he’d be dead.”

For this crime, as well as resisting arrest after the incident, Mikro was sent to a high-security adult prison, where he spent six months. He was the youngest inmate there, just 16. Once out, “They put me in an apartment. I had nothing to do. I like drugs. And it was just going downhill from there. I was selling weed—and other heavy drugs.”

As I listened to Mikro tell his story, it dawned on me that his biography, with its multiple personal grievances and setbacks and trials, mirrors that of the aggrieved and alienated jihadist. I shared this observation with him, and he readily agreed. “I come from the same shit,” he said.

The U.S. Department of State has made its own efforts to beat ISIS at the Twitter game. Earlier this year, I interviewed Alberto Fernandez, then in his final week as the head of the State Department’s Center for Strategic Counterterrorism Communications (CSCC). Fernandez spoke with disarming honesty and acuity about the myriad difficulties of derailing ISIS’s narrative and blunting its appeal among disaffected and marginalized Sunni Muslims. At the time, the CSCC was under fire for its “Think Again Turn Away” campaign, which the terrorism analyst Rita Katz had harshly denounced as inept and “embarrassing” in an article in Time. “We don’t have a counter-narrative,” Fernandez acknowledged. “We have half a message: ‘Don’t do this.’ But we lack the ‘Do this instead.’”

CtrlSec’s approach is far more straightforward. It is not about countering or repudiating a “narrative.” It is not about engaging with the undecided—the so-called “fence-sitters”—about the legitimacy of jihadist violence. It is not about winning hearts or changing minds. Rather, it is about shutting down the message at its source. And unlike the CSCC, CtrlSec has a clear metric for success: suspended Twitter accounts.

One criticism leveled against activists like those involved with CtrlSec is that they’re casting too wide a net and targeting non-ISIS accounts. Mikro acknowledged that this happens, but insisted that it’s rare and that mistakes are quickly corrected. For example, some parody ISIS accounts that initially fell afoul of CtrlSec were added to the group’s “whitelist” to prevent future mistakes.

A related criticism is that Twitter suspension undermines the democratic ideal of free speech. “That’s bullshit,” Mikro fired back before I could finish articulating the complaint. “Why should somebody who doesn’t let other people practice free speech have free speech? We’re saving lives.”

I tried to get Mikro to tell me more about what’s driving him. State counterterrorism agents are usually paid for their efforts, but this man devotes a huge amount of time and energy to his calling without any financial reward—and at no small personal risk. He told me he was spurred to action by the Charlie Hebdo attacks in January: “I had to do something. You can’t kill so many people over a fucking drawing.” He realized then, he said, that “sooner or later, if you don’t do shit, it’s gonna be your problem, too.”

But when I asked him what was going on in his life at the time, he said, “I was doing nothing.” CtrlSec has clearly filled that void. “I no longer know what else to do,” he reflected. “If I didn’t do this, I’d do exactly the same thing: I would sit at home, smoke weed all day. Only difference now is that I actually feel like I’m doing something productive.” When I asked him how he felt when he heard the news about the thwarted plot in Tunisia, he said, “That was like an orgasm, seriously.”

Not long after I returned to the U.K. from visiting him, Mikro sent me a text message. “Something big is happening,” he wrote, adding, “it’ll be a long night.” His ominous words were followed by a smiley face.