The President and the Press

“This crowd came in like an occupying army. They took over the White House like a stockade, and the Watergate, and screw everybody else. They have no sense that the government doesn’t belong to them, that it’s something they’re holding in trust for the people.”

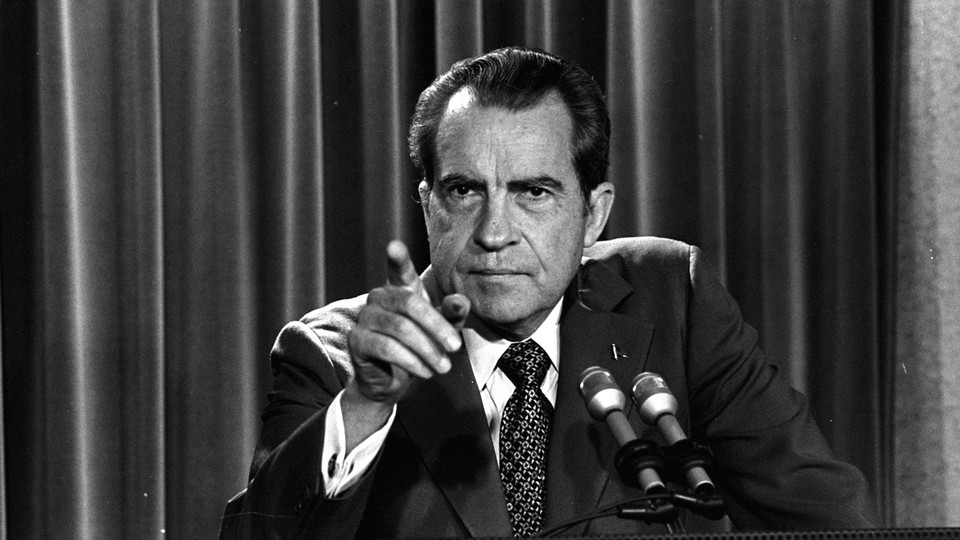

“I was determined to tell my story directly to the people rather than to funnel it to them through a press account.” — Richard Nixon, Six Crises

President Richard Nixon was in a good mood.

He had left Bucharest that afternoon; now his plane touched down at Mildenhall Air Force Base, England, the last stop on what had been a successful journey around the world. The crowds cheered the President along the way. Only two weeks earlier, on July 20, 1969, the United States had become the first nation to land men on the moon.

Prime Minister Harold Wilson had gone to the Air Force base, eighty-five miles north of London, to greet the President. As he chatted informally with Wilson at a reception at the officers’ club, Nixon said he planned to send moon rocks to every chief of state. At the time, there was a good deal of concern, later discounted, that germs might exist on the moon to which earthlings had no immunity. Because of these fears of real-life Andromeda Strain, the Apollo 11 astronauts had been sealed up in a capsule and quarantined upon their return from outer space. Well aware of this, Nixon told Harold Wilson that he also had another gift in mind. He might find a few “contaminated” pieces of the moon, he said, and give them to the press.

Nixon was, of course, joking, but the story revealed with clarity his attitude toward, and relations with, the news media. Nixon’s bitterness toward the press is legendary, perhaps best symbolized by his now classic remark after his defeat in the 1962 gubernatorial race in California: “You won’t have Nixon to kick around any more. …” On the other hand some of the men who went to work for Nixon after he became President have often left the impression that they would very much enjoy kicking around the press.

On election night, 1968, fifteen minutes after Richard Nixon issued his victory statement, about twenty GOP advance men gathered in the empty ballroom of the Waldorf-Astoria in New York to accept congratulations from John Ehrlichman, their chief. The happy, elated Nixon workers next heard from J. Roy Goodearle, a tall, beefy Southerner who was Spiro Agnew’s chief advance man (and later the Vice President’s principal political liaison with Republican Party leaders).

“Why don’t we all get a member of the press and beat him up?” he asked. “I’m tired of being nice to them.”

Unbeknownst to Goodearle, Ehrlichman, or the other advance men, Joseph Albright, then Washington bureau chief for Long Island’s Newsday, was standing in the room and wrote down the remark. Goodearle does not deny it; Agnew’s former press secretary, Victor Gold, speaking for Goodearle, insisted to me that “it was a joke.” “Perhaps so,” says Albright, “but nobody laughed.”

In the spring of 1972, columnist Nicholas Thimmesch of Newsday was invited by Jack Valenti to a private advance screening of The Godfather at the Washington headquarters of the Motion Picture Association of America. Seated in the small theater, Thimmesch suddenly felt someone grab his hair from behind and yank his head back sharply against the seat.

When Thimmesch was able to turn around he saw that the hair-puller was the President’s chief of staff, Bob Haldeman, about whom Thimmesch had recently written a somewhat critical profile. (The article termed Haldeman’s manner “brusque” and “clinical,” and quoted Haldeman as saying: “I guess the term ‘sonofabitch’ fits me.” Haldeman’s crew cut, the profile added, “hasn’t changed since the beginning of the cold war.” Despite this column, Thimmesch was held in exceptionally high regard by the Nixon-Administration.) Apparently Haldeman did not approve of the length of Thimmesch’s hair.

“Oh, pardon me,” said Haldeman, “I thought it was a girl sitting there.”

It was the newspapers that broke the story of the “Nixon Fund” during the 1952 presidential campaign—the $18,235 collected from wealthy contributors to help pay for his political expenses, or as Nixon put it, “to enable me to continue my active battle against Communism and corruption.” As pressure mounted over the fund, General Eisenhower threatened to force Nixon to resign as the Republican nominee for Vice President. Nixon prepared to deliver his famous televised “Checkers” speech.

“My only hope to win,” he wrote in his book Six Crises, “rested with millions of people I would never meet, sitting in groups of two or three or four in their livingrooms, watching and listening to me on television. I determined as the plane took me to Los Angeles that I must do nothing which might reduce the size of that audience. And so I made up my mind that until after this broadcast, my only releases to the press would be for the purpose of building up the audience which would be tuning in. Under no circumstances, therefore, could I tell the press in advance what I was going to say or what my decision would be. … This time I was determined to tell my story directly to the people rather than to funnel it to them through a press account.”

And so Nixon went before the television cameras. He invoked Pat’s Republican cloth coat, his little girl, Tricia, and his little black and white cocker spaniel dog (“regardless of what they say about it, we are going to keep it”). The public response was overwhelmingly favorable; Nixon flew to Wheeling, West Virginia, to meet Eisenhower, wept on Senator William Knowland’s shoulder, and stayed on the ticket.

But the lesson of all this was not lost on Nixon: the newspapers had threatened his political career; television had saved it. The words in Six Crises remained a manifesto and guideline to his dealings with the press. The way to deal with newspapers was to tell them very little, build up suspense, and then go over their heads to the people via television.

Nixon can keep track of what the networks and news media are saying about him through the “President’s Daily News Briefing,” the highly detailed private digest prepared for him by his speechwriting staff. Copies are not meant for public consumption, of course, but when the President was in China in February, 1972, a reporter got hold of one, and it showed that, even in Peking, Nixon could read what was being written and said about him in fantastic detail.

Television reports, for example, had obviously been clocked with a stopwatch, since the precise number of minutes and seconds of each network story was given, for example: “NBC led with 5:20 from the banquet … 1:30 of RN toast and 1:20 by Chou.” This meant Nixon could tell by a glance at the summary that American viewers watching NBC-TV got ten seconds more of Nixon than of Chinese Premier Chou En-lai. The log, which covered February 25, went on to say that NBC’s Herb Kaplow had done a two-minute report from the Forbidden City. “Both better film and audio of RN than was the case in live coverage.” For the “2nd night in a row,” the summary noted somewhat sourly, “CBS led with busing story.”

In discussing coverage by CBS—which has not been the Nixon Administration’s favorite network—the digest said: “Still frustrated in getting news was Cronkite … as he said reporters were again turning to sightseeing.” White House correspondent Dan Rather, the log said, did a report on acupuncture. “We saw a fellow under lung surgery—no pain. Then Dr. Dan in his operating room outfit concluded if it was all as it had been demonstrated, and he gave no reason to cause one to think it was otherwise, the operations witnessed were ‘amazing.’” The sardonic reference to Rather as “Dr. Dan” implicitly questioned his ability to make medical judgments; and the tone of the President’s news summary suggested that Rather had clearly been taken in by acupuncture and those clever Chinese. The log concluded with several single-spaced pages of reports on newspaper coverage of the trip, quoting headlines and going into great detail about treatment of the news, photographs, cartoons, and editorials.

One can only speculate about the cost, the tremendous effort, and the man-hours it must take to monitor the television networks and dozens of newspapers in such minute detail every day, then boil it down into written form, assemble it, and when the President is out of Washington—transmit it to him.

The Administration sees political advantage in attacking the press, says Hugh Sidey of Time, “but don’t discount their general hostility toward the press. It bubbles to the surface all the time. I once asked JFK what ever possessed him to call the steel men SOB’s. He said, ‘Because it felt so good.’ Some of that is here in the attacks on the press. Under Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson, the staff guys would bitch and moan about us, but there was always a sense of public trust, that they were awed by the responsibility given to them, and they understood this and would talk about what they were doing. They would talk about things. You could talk, write about, or disagree with them, but at the end of the day you could have a drink with them. There is no sense of that with these people.

“This crowd came in like an occupying army. They took over the White House like a stockade, and the Watergate, and screw everybody else. They have no sense that the government doesn’t belong to them, that it’s something they’re holding in trust for the people.”

“We feel the general pressure,” says Tom Wicker, associate editor and columnist of the New York Times. “No administration in history has turned loose as high an official as the Vice President to level a constant fusillade of criticism at the press. The Pentagon Papers case was pressure of the most immense kind. You have the Earl Caldwell case. If they indict Neil Sheehan, it will be pressure. In a sense, even the Ellsberg indictment is a form of pressure.

“There is a constant pattern of pressure intended to inhibit us. What the lawyers call a chilling effect. To make us unconsciously pull in our horns.” In December, 1971, Wicker said, he had received a telephone call from James Reston: “Scotty called me from Washington. I was in New York, and something had come up about the Sheehan case. I said, ‘I don’t think we ought to talk about this on the phone.’ I don’t know if they were listening. But if they can make us feel that way, hell, they’ve won the game already.”

One comes away from an interview with presidential press secretary Ronald Ziegler with the feeling of having sunk slowly, hopelessly, into a quagmire of marshmallows. But unless a newsman is out of favor, Ziegler is at least accessible to the press. To an unprecedented degree in the modern presidency, President Nixon is not.

Ziegler says that there has been no intent to intimidate the press. “Unless the press can point to efforts on the part of the government to restrain them, they shouldn’t care. I suppose if we were in a debate, someone would point to the Pentagon Papers. I feel the government had to take that view, do what they did.” Ziegler paused. “And after all,” he said, “the Pentagon Papers were published.”

The executive suite on the thirty-fifth floor of the Columbia Broadcasting System skyscraper in Manhattan is a tasteful blend of dark wood paneling, expensive abstract paintings, thick carpets, and pleasing colors. It has the quiet look of power. Over breakfast in the small private dining room of the executive suite, Frank Stanton, the president of CBS for twenty-five years, talked candidly about the relationship between government and the television industry. I was interested, I explained, in pressures by government on the TV networks. I particularly wanted to know about telephone calls from Presidents; I recognized that this was a delicate subject, but I assumed that as head of CBS he had received some. He had, as it turned out, from several Presidents.

“I had a curious call from LBJ,” he said. “It was one night back in 1968, at the time of the Democratic platform committee hearings in Washington.” Johnson called on a Tuesday, Stanton said; it was August 20, and Dean Rusk was scheduled to testify at an evening session of the committee. As Stanton recalled the conversation, it went as follows:

LBJ: Are you going to cover Dean Rusk tonight?

STANTON: Yes. We’re covering the whole thing.

LBJ: No, I mean are you going to cover it live?

STANTON: Why?

LBJ: Rusk has an important statement.

STANTON: If you’re saying Rusk is going to have an important statement, we’ll cover it live. But he has to be there on time.

LBJ: OK, just tell me the time—I’ll have him there.

STANTON: Well, 9:00 P.M. But you really have to get him there on time. We’ll be cutting into the Steve Allen show, and people are going to be furious if there is nothing going on.

Stanton knew that the Steve Allen show (which on that night starred Jayne Meadows and the Rumanian National Dance Company) began at 8:30 P.M. and ran for one hour; viewers would naturally be disappointed, he reasoned, if time were preempted for a political broadcast and the screen showed an announcer doing “fill.” The CBS president had visions of the Secretary of State arriving late and the television audience getting nothing: no Steve Allen, no Jayne Meadows, no Rumanian dancers, not even Dean Rusk.

The conversation with President Johnson continued:

STANTON: How long will Rusk speak?

LBJ: Not long—why?

STANTON: We’ve got a special on blacks coming on at 9:30 P.M. and I don’t want Rusk to collide with that.

The President assured Stanton there was no need to worry; the Secretary of State would be there on time, and he would be off before the special.

Johnson was true to his word. Precisely at 9:00 P.M. CBS correspondent Roger Mudd began introducing the broadcast from a booth in the hall.

“Suddenly,” Stanton said, “you could see Mudd look up, startled. Rusk was starting in right at 9:00 P.M., straight up.”

The President of the United States had called the president of CBS and sweet-talked Steve Allen off the air and the Secretary of State on the air, in prime time, for a specific political reason, which he did not share with Stanton. That afternoon Democratic liberals had circulated a draft plank for the party platform calling for a halt to the bombing of North Vietnam. Lyndon Johnson wanted Dean Rusk on nationwide television, at an hour when he would have maximum exposure, to head off the inclusion of any such plank in the platform.

Rusk followed his marching orders. “We hear a good deal about stopping the bombing,” he said. “… If we mean: Let them get as far as Dupont Circle but don’t hit them while they are at Chevy Chase Circle, that would be too rude, let us say so.” The party platform, Rusk said, should “state objectives” but not outline “tactics or strategy.” In other words, no antibombing plank.

Rusk, in fact, made no important announcement; but presumably Johnson had to tell Stanton something to justify handing over the network to the President at 9:00 P.M. As it turned out, however, viewers were treated to a drama that was entirely unexpected, even by the President. Just as Rusk was finishing his twenty-five minute statement, he was seen being given a piece of wire copy announcing the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia.

In plain view of the television audience, Rusk huddled with platform committee chairman Hale Boggs for a moment, and then announced: “I think I should go see what this is all about.” And he hurried away.

Stanton, of course, had been watching CBS, waiting for that important statement. About twenty minutes later he got a call from the President. Did Rusk show up on time? Johnson wanted to know. Yes, said Stanton, hadn’t the President been watching?

“No. Dobrynin came in to tell me what happened [in Czechoslovakia] and I’ve been tied up. I’ve just convened the National Security Council.”

“Can I use that?”

“Yes.”

“Excuse me, I want to tell our people this.”

Stanton hung up and passed on his scoop to CBS News.

It eventually became known that a summit meeting between Johnson and the leaders of the Soviet Union was to have been announced at the White House the next morning, August 21. But the Czech invasion killed the projected meeting, to Johnson’s bitter disappointment, and there was never any White House announcement that it had even been contemplated. In retrospect, Stanton harbored some suspicion that Rusk had planned to announce the summit meeting that night on CBS. Now Stanton was a very old and close friend of Lyndon Johnson’s, and he was understandably reluctant to think that the President might have been fibbing to him about Rusk having an “important statement.”1

When the President of the United States wants network time, he calls up and gets it. Or he has one of his assistants call. Not only Lyndon Johnson, but all recent Presidents have had a consuming interest in television. The medium has a fascination for Presidents, an interest that is easily understood, since so much of their political success depends on the skill with which they use it.

A telephone call from a President to the publisher of the New York Times, for example, is not an unknown event, but one cannot, somehow, picture Lyndon Johnson calling up Arthur Ochs Sulzberger and saying: “Punch, Dean Rusk is going to have an important announcement tonight, and I want you to give it page-one treatment, eight-column head with full text and pictures. What time does your Late City close?”

But when a President calls the head of CBS, or NBC, or ABC, it is not easy, or even advisable, to brush him off. In the fall of 1971, Julian Goodman, the president of NBC, went to Rome for a staff meeting of NBC correspondents in Europe. One of the reporters at the private meeting complained that Nixon was “using” the television networks to speak to the American people whenever he pleased, for free; he had done so something like fourteen times up to that date.

Goodman agreed. But the correspondent persisted. “Julian, what is your attitude toward President Nixon’s requests for television time?”

“Our attitude,” said Goodman evenly, “is the same as our attitude toward previous Presidents: he can have any goddamn thing he wants.”

Sometimes a presidential aide or appointee manages to act as a buffer between the White House and the networks. Newton Minow, the Chicago attorney whom President John Kennedy made chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, recalls that Kennedy once expressed dissatisfaction with NBC News.

One night in April, 1962, Minow said, in the midst of Kennedy’s fight with the steel companies, the Huntley-Brinkley show on NBC included “a long speech by somebody who took the President apart. I happened to have watched it. We were having a small dinner party at home and I was getting dressed when my wife said ‘The President is on the phone.’” As Minow recalled the conversation, it went this way:

JFK: Did you see that goddamn thing on Huntley-Brinkley?

MINOW: Yes.

JFK: I thought they were supposed to be our friends. I want you to do something about that. You do something about that.

Minow said that the President did not, as the story later got around in the television industry, ask that the FCC chairman take Huntley-Brinkley off the air. But, said Minow, the President “was mad.”

Minow added: “Some nutty FCC chairman would have called the network. Instead I called Kenny O’Donnell [Kennedy’s appointments secretary] in the morning and I said to him, ‘Just tell the President he’s very lucky he has an FCC chairman who doesn’t do what the President tells him.’”

When a President desires to make a television broadcast, there are standing arrangements to handle his request, procedures worked out between the White House and the Washington bureaus of the major networks. At the time Lyndon Johnson was President, the networks told the White House they needed six hours to make the technical arrangements for a White House broadcast; they could do it in three, they said, but could not guarantee a good picture, or any picture. Despite this, Johnson often demanded instant access to the networks and got on the air within one hour.

Johnson used TV so frequently that finally he asked for—and the networks agreed to provide—“hot cameras,” manned throughout the day in the White House theater, with crews continually at the ready. Johnson could then walk into the theater and go on the air live, immediately. During the Dominican crisis he went on television on such short notice that he burst into the regular network programming with almost no introduction, startling millions of viewers.

“Once Johnson went on the air so fast,” an NBC executive recalled, “that we couldn’t put up the presidential seal. When a network technician said we need a second to put up the seal, Johnson said, ‘Son, I’m the leader of the free world, and I’ll go on the air when I want to.’”

There is a seeming paradox in Richard Nixon’s view of television. On the one hand, television saved his political career in 1952, and he has often had kind words for the medium. Note, for example, that in his 1962 false exit (“You won’t have Nixon to kick around any more”), he stated: “Thank God for television and radio for keeping the newspapers a little more honest.” As President, he told Cyrus Sulzberger in 1971: “I must say that without television it might have been difficult for me to get people to understand a thing.”

On the other hand, as President, Nixon criticized the networks. It was with Nixon’s blessing that Spiro Agnew launched his celebrated attack on network news analysts. Nixon’s Administration has made systematic efforts to cow the networks and destroy the credibility of the press, including television news.

There is no inconsistency, however, if one understands that in Nixon’s view television ideally should serve only as a carrier, a mechanical means of electronically transmitting his picture and words directly to the voters. It is this concept of television-as-conduit that has won Nixon’s praise, not television as a form of electronic journalism. The moment that television analyzes his words, qualifies his remarks, or renders news judgments, it becomes part of the “press,” and a political target.

In discussing Nixon and television, therefore, one must distinguish between television as a mechanical means of communication and television as an intellectual instrument. “Pure” television is OK, television news is not. As President, Nixon’s use of television flows logically from these basic premises. Thus at every opportunity Nixon solemnly addresses the nation, but he has usually avoided the give-and-take of the televised news conference. Only in the first setting does Nixon have total control—except for the analyses afterwards by network newsmen, which Spiro Agnew’s attacks were specifically designed to discourage. In short, to Richard Nixon, television ideally is the mirror, mirror on the wall.

In April of 1971, John Ehrlichman, the President’s chief assistant for domestic affairs, complained in person to Richard S. Salant, the president of CBS News, about Dan Rather, the network’s White House correspondent. Ehrlichman was in New York to appear on the CBS Morning News with correspondent John Hart. Afterwards Hart and Ehrlichman adjourned for breakfast at the Edwardian Room of the Plaza, where they were joined by Salant. The President’s assistant brought up the subject of CBS’s White House reporter.

“Rather has been jobbing us,” Ehrlichman said. Salant, seeking to inject a lighter note into the conversation, told how Rather had been hired by CBS in 1962 after he had saved the life of a horse, an act of heroism that resulted in considerable publicity and brought him to the attention of the network. It was then that Rather went to work for CBS News as chief of its Southwest bureau in Dallas. When President Kennedy was assassinated in that city, Rather went on the air for the network, and his cool, poised coverage of the tragedy gained him national recognition. After Dallas, Salant explained to Ehrlichman, CBS brought Rather to Washington, in part because the new President, Lyndon Johnson, was a fellow Texan.

“Aren’t you going to open a bureau in Austin where Dan could have a job?” Ehrlichman asked Salant. He then accused Rather of never coming to see him in the White House, and he suggested it might be beneficial if Rather took a year’s vacation. That evening, following a presidential press conference at the White House, Ziegler told Rather cryptically that President Nixon’s obvious failure to recognize him at that conference had “no connection” with something that “you are about to hear.”

Rather heard the next morning. Salant telephoned William Small, head of the CBS Washington bureau. Small called Rather in and told him about the breakfast at the Plaza; he assured Rather that his standing with CBS was not affected. He said he was mentioning the episode simply because sooner or later Rather was bound to learn about it. Rather told Small it was true he had not seen much of Ehrlichman at the White House—because Ehrlichman would not see him.

Now, however, Ziegler urged Rather to see Ehrlichman and talk the situation over. When Rather walked into Ehrlichman’s office, he found Haldeman waiting there as well. The conversation, with just the three men present, was blunt on both sides. As Rather reconstructed it, the dialogue proceeded as follows:

EHRLICHMAN: I wanted to tell you to your face I wasn’t in New York for this purpose. … I didn’t know there was going to be a breakfast. When the conversation went in the direction it did, I told them what I thought, which is I think you’re slanted. I don’t know whether it’s just sloppiness or you’re letting your true feelings come through, but the net effect is that you’re negative. You have negative leads on bad stories.

RATHER: What’s a bad story?

EHRLICHMAN: A story that’s dead-assed wrong. You’re wrong 90 percent of the time.

RATHER: Then you have nothing to worry about; any reporter who’s wrong 90 percent of the time can’t last.

HALDEMAN (breaking in): What concerns me is that you are sometimes wrong, but your style is very positive. You sound like you know what you’re talking about, people believe you.

EHRLICHMAN: Yeah, people believe you, and they shouldn’t.

RATHER: I hope they do, and maybe now we are getting down to the root of it. You have trouble getting people to believe you.

EHRLICHMAN: I didn’t say that.

At one point Ehrlichman complained that “only the President, Bob, and sometimes myself” knew what was going on, and “you’re out there on the White House lawn talking as though you know what’s going on.”

At the Plaza breakfast with Richard Salant, Ehrlichman had also singled out CBS correspondent Daniel Schorr for criticism. Schorr, said Ehrlichman, reported what the critics said about Nixon’s domestic programs, but not the Administration’s side. A few months later Schorr was under investigation by the FBI. Early on the morning of August 20, 1971, Ellen McCloy, Salant’s secretary, received a telephone call at CBS News headquarters on West Fifty-seventh Street in Manhattan. The call was from one Tom Harrington. “He’s the CBS FBI man,” Miss McCloy explained. “He always opens up his conversations by saying ‘Tom Harrington FBI.’”

He did so on this occasion, explaining to Miss McCloy that she would be getting a call from another FBI man “who is checking on Dan Schorr.” Salant was not in yet, so his secretary called him at home to alert him to the fact that the FBI was on the trail of a CBS correspondent. When the second agent called Miss McCloy, she gave him Salant’s listed number in New Canaan, Connecticut. “He was in a big rush,” Miss McCloy recalled. “He gave the impression he had to have the information right away.” The FBI man then called the CBS News president at his home, asking for the names of people who knew Dan Schorr. In the meantime Miss McCloy called Bill Small in Washington, Schorr’s boss, to let him know what was happening.

The FBI agent called Miss McCloy back twice. With Salant’s permission, she provided the names of other officials for him to talk to at CBS. Salant confirmed that the FBI agent who telephoned him presented the matter as “very urgent.” The sort of questions he was asked about Schorr, Salant said, were: “Was he loyal? Did he go around with disreputable people?”

Schorr, a gray-haired, bespectacled family man of fifty-five, and a veteran of twenty years at CBS, definitely did not have the reputation of hanging around with disreputable people. A serious, hardworking newsman, he specialized in covering health, education, welfare, the environment, and economics.

As Schorr recalls the sequence of events, it began on Tuesday, August 17, when Nixon, in a speech to the Knights of Columbus, promised that “you can count on my support” to help parochial schools. The producer of the CBS Evening News—the Walter Cronkite show—called Schorr and asked for a follow-up story. Schorr went to see a source, a Catholic priest active in the field of education, who told him the Administration was doing nothing to aid Catholic schools.

On Wednesday night Cronkite ran a film clip of Nixon’s speech promising to aid parochial schools, then cut to Schorr saying there was “absolutely nothing in the works” to help these schools. On Thursday, Alvin Snyder, the Administration’s deputy communications director for television, telephoned Schorr, asking him to come to the White House because “Peter Flanigan and others thought I didn’t have the facts.” Late in the day Schorr met at the White House with Pat Buchanan, Terry T. Bell, deputy commissioner of education, and Henry C. Cashen II, an assistant to Charles Colson, who was then special counsel to the President. “They began reading figures off very rapidly,” Schorr said. He suggested that they put their main points down on paper and said he would try to get it on the air.

On Thursday, the same day that Schorr was summoned to the White House, a member of the White House staff requested the FBI to investigate the CBS correspondent.

On Friday morning Schorr reported to the CBS studios in Washington. An FBI agent was already there questioning Small, who declined to answer until he knew the reason. “I don’t know except it has to do with government employment,” the FBI man said. Not having learned much from Small, the agent then wandered over to Schorr’s desk and started asking routine questions—age? family? occupation?

Without thinking, Schorr began answering, then suddenly stopped and said he would not say anymore until the agent specified what employment he was talking about. Since the agent would not or could not, Schorr refused to answer any further questions.

“Is that what you want me to report?”

“Yes.”

“Do you mind if I ask other people about you?”

“Yes.”

Schorr explained to the agent that he was in a “highly visible” occupation; it would soon get around that he was being investigated and it might seem as though he was looking for a job. And that, Schorr explained, could be harmful to his reputation and position at CBS.

“All the rest of the day,” Schorr said, “calls came in from all over from people who said they had been approached by the FBI. Fred Friendly [the former president of CBS News] called from his vacation home in New Hampshire. They had telephoned him and asked to see him, but he said he would not talk to them without checking with me. They called Bill Leonard and Gordon Manning, both vice presidents of CBS News. They called Ernie Leiser, the executive producer of CBS specials. Sam Donaldson of ABC was called. Irv Levine of NBC, who was with me in Moscow, was called; they wanted to know how I carried on as a correspondent in Moscow.” When some of those questioned asked why the FBI was making these inquiries, they were told that Dan Schorr was being considered for a high government post, a position of trust.

Then Schorr discovered that “the FBI had talked to my neighbors, including Marjorie Hunter of the New York Times.” One neighbor reported that Schorr’s home had apparently been under surveillance. By now Schorr was determined to know more. “There were two theories at CBS: first, that it was a real employment investigation, and second, that it was an adverse investigation as a result of my stories on Catholic school aid. But if there was a job involved, where the hell was it?”

On November 11, the Washington Post published a detailed front-page story about the FBI investigation. The story said the probe had been initiated by the office of Frederic V. Malek. As personnel man in the White House, Malek earned a reputation as “the Cool Hand Luke” of the Nixon Administration.

The storm broke over Ron Ziegler at the White House morning press briefing. Schorr, Ziegler told newsmen, was being checked for a job in “the area of the environment.” Malek, Ziegler added, was in charge of searching “across the nation” for “qualified people.” Claiming “I am trying to be forthright with you,” Ziegler nevertheless repeatedly ducked the simple, direct question of who had ordered the FBI investigation. He kept saying that “… it was part of the Malek process.” But the transcript of the briefing does include this exchange:

Q.: Is it your understanding Mr. Malek was aware that an FBI check was under way?

ZIEGLER: Yes.

In an interview published the next day, Malek seemed to imply that there had been a full field FBI probe. Malek said someone on his staff—again unidentified—had asked the FBI to investigate Schorr but “the message somehow got bungled. Somehow something went wrong. Either I wasn’t clear on what I wanted or the staff wasn’t clear or the FBI. A breakdown occurred.”

Something indeed had gone wrong, and Senator Sam J. Ervin, Democrat of North Carolina, a Southern defender of constitutional liberties, announced a Senate investigation of the episode.

“Job or no job,” Schorr told the Ervin committee, “the launching of such an investigation without consent demonstrates an insensitivity to personal rights. An FBI investigation is not a neutral matter. It has an impact on one’s life, on relations with employers, neighbors, and friends.”

Considering the Administration’s protestations of innocence, it was surprising how little cooperation Ervin received. The President declined to let any staff member testify—Malek, Herbert Klein, and Colson all refused invitations—but the White House sent a letter to Ervin, saying that Schorr “was being considered for a post that ‘is presently filled.’” The letter was signed by John W. Dean III, counsel to the President. Nixon, the letter added, had decided that such job investigations in the future would not be initiated “without prior notification to the person being investigated.” On the same day the letter was published, the Washington Post quoted an unnamed White House official as saying that the job for which Schorr had been investigated was that of assistant to Russell E. Train, the chairman of the Council on Environmental Quality. The story indicated that the Administration thought Schorr might produce a series of television programs on the environment.

The leak was not entirely convincing, since Train had no assistant producing TV shows, and the White House letter to Ervin distinctly said the job was “presently filled.” In fact, the council had no one with the title or duties of assistant to the chairman; no such job existed.

Much of the pressure by government on the networks takes place out of public view. The telephone calls from White House assistants and the visits to network executives by presidential aides are seldom publicized. For the most part, however, it is CBS that feels the greatest pressure under the Nixon Administration. The official who bears the brunt of that pressure is Richard Salant, the president of CBS News.

Salant, a lawyer turned news executive, occupies a high-pressure job; he wears glasses, has a receding hairline, and chain-smokes. Unlike some network executives, he is unusually outspoken. Salant reeled off a list of pressures from and contacts with CBS emanating from the Administration.

In February of 1971, he said, CBS did a segment on Agnew on the program 60 Minutes. Narrator Mike Wallace reported that Agnew’s grades at Forest Park High School “were mediocre at best.” CBS asked to see the grades, Wallace added, “but school principal Charles Michael told us Agnew’s record was pulled from the file when he became Vice President.” The program, tracing Agnew’s early career, also noted that he once served as personnel director at a supermarket and, like other employees, “Agnew often wore a smock with the words ‘No Tipping Please’ on it.”

After the broadcast, Salant said, the President’s director of communications, Herbert Klein, telephoned him. “Klein called and said he wanted to see me. He came to New York and came to my office and made small talk. Then he got around to the point; he said the Vice President didn’t see 60 Minutes, he never looks at those things. But Mrs. Agnew saw it and didn’t like it.”

Salant told Klein that 60 Minutes had broadcast letters from viewers who did not like the Agnew program; CBS would be happy to receive a letter from Mrs. Agnew.

Once Klein telephoned Reuven Frank, then president of NBC News, to protest a broadcast by David Brinkley. Frank became so furious that he stormed next door into the office of Richard C. Wald, then vice president of NBC News (later Frank’s successor), to let off steam.

“Relax,” said Wald, “he gets paid to call you.”

A few days later on a Saturday morning, the White House telephoned Frank at home. Frank was annoyed since he was kept waiting on the line, it was his day off, and he hadn’t had his breakfast yet. He started to do a slow burn again. Finally Klein came on. He was calling, he announced cheerily, to say he had seen something he liked on NBC; he just wanted Frank to know.

It may be that no single example of government power directed at television news means very much—Dan Rather survived John Ehrlichman’s bemoanings, Salant’s sympathy for Judy Agnew was limited, and so on—but taken together, such incidents constitute a pattern of pressure that has dangerous implications. It is by means of such contacts that political leaders attempt to influence the presentation of the news so as to put the government in the most favorable light.

The First Amendment clearly protects the printed press. But the Founding Fathers, after all, did not foresee the advent of television, and the degree to which broadcasting is protected by the First Amendment has been subject to shifting interpretation. Technology has outpaced the Constitution, and the result is a major paradox: television news, which has the greatest impact on the public, is the most vulnerable and the least protected news medium.

Only economics limits the number of newspapers and magazines that may be published. But the number of radio frequencies and television channels is finite; the rationale for government regulation is that stations would otherwise overlap and interfere with each other. Cable television may one day erode the technological argument for government regulation by opening up an unlimited number of channels, but for the moment the networks remain under government supervision and the Dean Rusks will continue, when they want to, to replace the Steve Allens and the Rumanian dancers on short notice.

The government’s ultimate power over the networks is its ability to take away a license at renewal time and give it to someone else. Public television, dependent on Congress for funds, is even more susceptible to government intervention than the networks; the Nixon Administration has made no secret of its discontent with public television.

Walter Cronkite believes the Nixon Administration attacked the news media “to raise the credibility of the Administration. It’s like a first-year physics experiment with two tubes of water—you put pressure on one side and it makes the other side go up or down.” He added: “I have charged that this is a ‘conspiracy.’ I don’t regret my use of that word.”

By applying constant pressure, in ways seen and unseen, the leaders of the government have attempted to shape the news to resemble the images seen through the prism of their own power. The Administration’s attacks, Richard Salant acknowledged, have “made us all edgy. We’ve thought about things we shouldn’t think about.”

- Johnson’s personal relationship with Stanton dated back to the early 1940s. Johnson, then a congressman, went to New York looking for a network affiliation for KTBC, the Johnson family radio station in Austin. No one at CBS was too enthusiastic about adding a small-power station in Austin to the network. At the time, stations in Dallas and San Antonio covered Austin fairly well. Stanton was then in charge of research for CBS; it was his job to know whether stations overlapped or did not. Stanton pointed out that Austin filled in just a little crack between San Antonio and Dallas. KTBC got its valuable CBS affiliation; later, in 1952, it acquired a television channel (also a CBS affiliate) and Johnson became a multimillionaire. The radio and television station were the cornerstone of the Johnson family fortune, estimated, after Lyndon Johnson’s death, at some $20 million. ↩