Toward Happy Civilization

A traveler plots an escape from a rural train station. A short story

He’s lost his ticket, and from behind the ticket window’s white bars, the station agent refuses to sell him another, saying there’s no change in the drawer. From a station bench, he looks at the immense, dry countryside that opens out to either side. He crosses his legs and unfolds the pages of the newspaper in search of articles that will make the time pass faster. Night begins to cover the sky and far away, above the black line where the tracks disappear, a yellow light announces the afternoon’s last train. Gruner stands up. The newspaper hangs from his hand like an obsolete weapon. In the ticket window he discerns a smile that, half hidden behind the bars, is directed exclusively at him. A skinny dog that had been sleeping now stands up, attentive. Gruner moves toward the window, confident in the hospitality of country people, in masculine camaraderie, in the goodwill that awakens in men when you handle them well. He is going to say, Please, how hard can it be? You know there’s no more time to find change. And if the man refuses, he’s going to ask about other options: Surely, sir, I could buy the ticket aboard the train, or I could buy it at the terminal’s ticket office when I arrive. Make me an IOU, give me a piece of paper that says I have to pay for the ticket later.

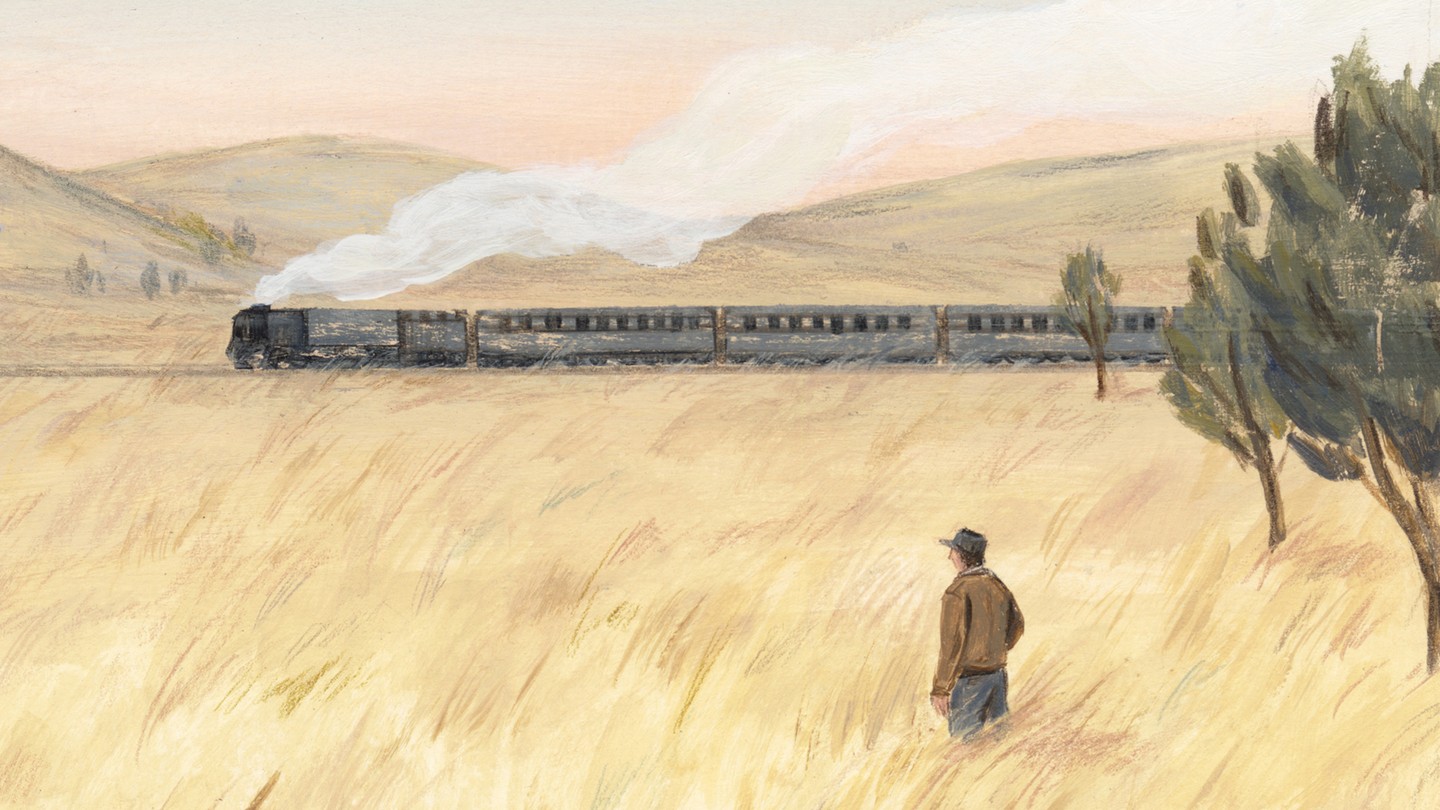

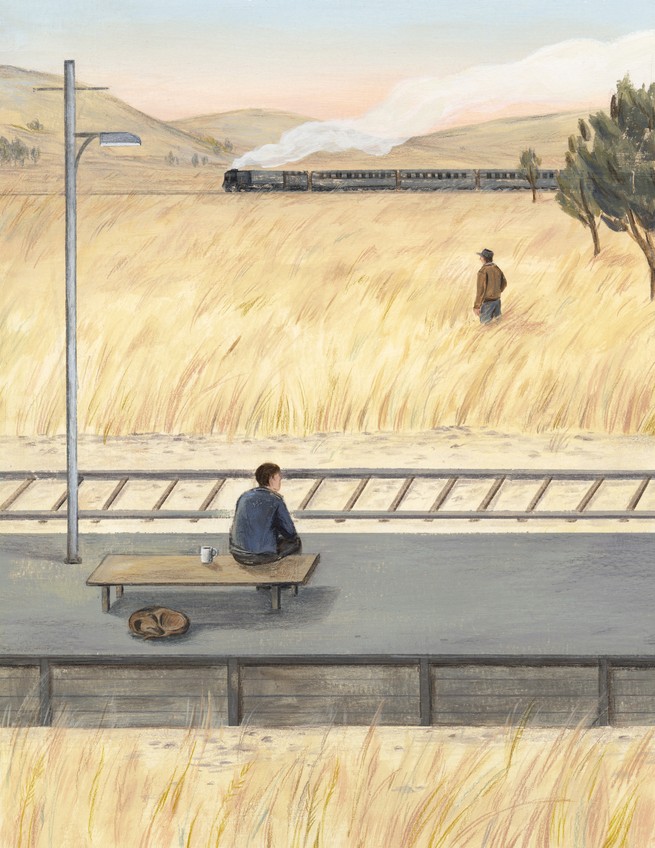

But when he reaches the window, when the train’s lights lengthen the shadows and the whistle is loud and intrusive, Gruner discovers that there is no one behind the bars, only a tall chair and a table overflowing with unstamped slips, future tickets to various destinations. As he watches the train enter the station at considerable speed, Gruner also sees that off to one side of the tracks, in the field, the still-smiling man is signaling to the conductor that he doesn’t have to stop, because no one has bought a ticket. Then, as the sound of the massive machine moves away, the dog lies down again and the station’s only lamp blinks for a few seconds before it goes out entirely. The now-crumpled newspaper comes to rest again on Gruner’s lap, and he reaches no conclusion that would drive him in search of that wretch who has refused him the capital’s happy civilization.

Everything is still and silent. Even Gruner, sitting at the end of a bench with the cool night seeping through his clothes, stays motionless and breathes calmly. A shadow that he doesn’t see moves between posts and plaza benches and reveals itself as the man from the ticket window. Now unsmiling, he sits at the other end of the bench and puts a mug full of steaming liquid down next to him. He pushes it until it’s a few inches from Gruner. The man clears his throat and looks at the wide black countryside that stretches out before them. As the steam from the mug awakens Gruner’s appetite, he focuses on resistance. He thinks that in the end, he will get to the capital somehow and he’ll report what has happened. But his hand moves toward the mug of its own accord, and the heat between his fingers distracts him. “There’s more where that came from,” says the man, and then Gruner—but, no, Gruner wouldn’t do that. Gruner’s hands raise the warm vessel to his mouth, where a miraculous medicine reanimates his body. With the last sip he understands that, if this were a war, the wretch would already have won two battles. Victorious, the man stands, picks up the empty mug, and walks away.

The dog is still curled up, its snout hidden between its stomach and hind legs, and although Gruner calls to him several times, the dog ignores him. It occurs to Gruner that maybe it was the dog’s food in the mug, and he worriedly wonders how long the dog has been here. Whether there had been a time when the dog had wanted to travel from one place to another, as he himself wanted to do that very afternoon. He has the notion that the dogs of the world are the result of men who have failed in their attempted journeys. Men nourished and retained with nothing but steaming broth, men whose hair grows long and whose ears droop and whose tails lengthen, a feeling of terror and cold inciting them to stay silent, curled up under some train-station bench, contemplating the failures of the newcomer who is just like them, only still has hope, staunchly awaiting the opportunity of a voyage.

A silhouette moves in the ticket office. Gruner stands up and walks decisively over. Steam from the heaters wafts out between the white bars, carrying homey smells. The man smiles with goodwill and offers him more broth. Gruner asks what time the next train passes. “In an hour,” says the man, and his offended hand shuts the ticket window and leaves Gruner alone once again.

Everything repeats like in a natural cycle, thinks Gruner an hour later, as he forlornly watches another string of cars go by without stopping, an exact copy of the previous train. In any case, morning will come soon and workers will arrive at the station to buy tickets, many of them probably with change. If there are trains to the capital, it is thanks to the passengers who must travel there every morning. Yes, as soon as I get to the capital I will report that man, thinks Gruner, and someday I’ll come back with change to this wretch’s station just to make sure he no longer works here. With the relief of that certainty, he sits on the bench and waits.

Time passes during which Gruner’s eyes get used to the night and read shapes in even the darkest places. That’s how he discovers the woman, her figure leaning against the waiting-room doorway, and he sees her hand waving to invite him in. Gruner is sure that the gesture is for him, and he stands up and walks toward her; she smiles and ushers him in.

On the table are three heaping plates, and the steam comes not from broth or dog food, but from substantial sausages bathed in an aromatic white cream. The room smells like chicken, cheese, and potatoes, and then, when the woman brings a casserole dish full of vegetables to the table, Gruner remembers the dinners typical of the capital’s happy civilization. The miserable ticket man, so elusive when Gruner wanted to buy a ticket, enters and offers him a seat.

“Have a seat, please. Make yourself at home.”

The man and woman begin to eat, satisfied. Gruner sits with them, his plate before him. He knows that, outside, the cold is damp and inhospitable, and he also knows he has lost another battle as he wastes no time in raising the first forkful of exquisite chicken sausage to his mouth. The food doesn’t guarantee he’ll get out of this station soon.

“Is there a reason you won’t sell me a ticket?” asks Gruner.

The man looks at the woman and asks for dessert. From the oven emerges an apple tart that is soon cut into even slices. The man and woman exchange a tender glance when they see how Gruner devours his portion.

“Pe, show him his room. He must be tired,” says the woman, and then the first mouthful of a second serving of tart stops en route to Gruner’s mouth, stops and waits. Pe stands up and asks Gruner to come with him.

“You can sleep inside. It’s cold out there. There are no more trains until morning.”

I have no choice, thinks Gruner, and he leaves the tart and follows the man to the guest room.

“Your room,” says the man.

I’m not going to pay for this, thinks Gruner, at the same time as he sees that the two blankets on the bed look new and warm. He’s still going to lodge a complaint; the hospitality doesn’t make up for what happened. The couple’s conversation reaches him faintly from the room next door. Before he drifts off, Gruner hears the woman tell Pe that he needs to be more considerate, the man is alone and this must seem strange, and Pe’s offended voice replying that the only thing that wretch cares about is buying his return ticket. “Ungrateful” is the last thing that reaches his ears; the sound of the word fades gradually and resurfaces in the morning, when the whistle of a train already passing the station wakes him up to a new day in the country.

“We didn’t wake you because you were sleeping so soundly,” says the woman. “I hope you don’t mind.”

Hot coffee with milk, and cinnamon toast with butter and honey. While Gruner stubbornly and silently refuses breakfast, his eyes follow the woman’s steps as she cooks what will apparently be lunch. Then something happens. An office worker, a man with Asian features and dressed like Gruner, someone who is possibly taking the next train and has enough change for two tickets, comes into the kitchen and greets the woman.

“Morning, Fi,” he says, and with a son’s affection he kisses the woman on the cheek. “I’m finished outside. Should I help Pe in the field?”

Once again, the food that was moving toward Gruner’s mouth, in this case a piece of toast, stops halfway and hangs in the air.

“No, Cho, thanks,” says Fi. “Gong and Gill already went, and three are enough for the job. Could you get a rabbit for supper?”

“Sure,” replies Cho, who, with apparent enthusiasm, takes the rifle hanging next to the chimney and withdraws.

Gruner’s toast returns to the plate and stays there. Gruner is going to ask something but then the door opens, and in comes Cho again. He looks at Gruner and then curiously asks the woman: “Is he new?”

Fi smiles and looks affectionately at Gruner.

“He got here yesterday.”

Gruner’s actions that first day are the same as those of everyone who has ever been in his situation. Hide away offended and spend the morning next to the office that sells tickets for a train that doesn’t stop. Then refuse to eat lunch and, in the afternoon, secretly study the group’s activities.

Under Pe’s instructions, the office workers work the earth. Barefoot, their pants rolled up to the ankles, they smile and laugh at their own jokes without losing the rhythm of their tasks. Then Fi brings tea for them all, and the four of them—Pe, Cho, Gong, and Gill—signal to Gruner, who thought he was hidden, inviting him to join the group.

But Gruner, as we know, refuses. No one is more stubborn than an office worker like him. Even when he’s in the country, he still has his pride—held over from offices with no partitions, but with a telephone line all his own—and, sitting on a wooden bench, he struggles not to move all afternoon long. Even if no train stops, he thinks. Even if I rot right here.

The night gathers everyone together in the preparation of a warm family meal as the lights of the house turn on one by one and the first aromas of what will be a great feast escape into the cold through the cracks under the doors. Gruner, his patience and pride attenuated by the passage of the day, gives up guiltlessly and prepares to accept the invitation: a door that opens and the woman who, as on the previous night, invites him in. Inside, a familial murmur. Pe congratulates the office workers with brotherly slaps on the back. The workers, grateful for everything, set a table that reminds Gruner of the intimate Christmas celebrations of his childhood and—why not?—of the capital’s happy civilization. A triumphant Cho—successful, satisfied hunter—serves up the rabbit. Pe and Fi sit at either end of the rectangular table. On one side are the three office workers, and all alone across from them sits Gruner. At Gong’s and Gill’s constant request he passes a saltshaker back and forth, though neither ever uses it. Finally, Pe discovers eager smiles tinged with mischief on Gong’s and Gill’s childish faces, and with a call to attention he grants Gruner the chance to abstain from the exhausting game so he can finally, now that night has fallen, taste his first mouthful of the day.

In the following days Gruner tries out various strategies. The first thing that occurs to him is to bribe Pe, or even Fi, for change. Then, with tears in his eyes, he offers to buy the ticket to the city in exchange for all his money: “No change,” he begs. “Keep it all,” he begs over and over again. And he listens desperately to a reply that speaks of a certain railroad code of ethics and the impossibility of keeping someone else’s money. Those are the days Gruner proposes to buy something from them. The amount of the ticket plus anything they want to sell him will be the sum total of his money—the perfect bargain. But no. And he has to bear the office workers’ stifled laughter, and then another family dinner.

The first of Gruner’s tasks to become routine are washing the dishes after dinner and, in the morning, preparing the dog’s food. Then he begs again. He offers to pay with his work. To pay for something, pay for lunch. Chip in little by little with the work of living in the country. Chat every now and then with the office workers. Discover incredible talents in Gong when it comes to theories of efficiency and group work. In Gill, a lawyer of great prestige. In Cho, a capable accountant. Cry once again in front of the ticket office, and at night offer to make lunch the next day. Hunt field rabbits with Cho, and suggest, in thanks for the family’s goodwill, compensating them at least for the delicious food. Manage to learn how this and that are done, and also try to pay for that all-important information, that the harvest is done in the morning when the sun won’t bother you, and the midday hours are spent on housework. And every once in a while, in the hope of getting change for a ticket—a hope that is reborn only on certain days—sit on the station bench and watch another train that, at Pe’s inevitable signal, passes without stopping.

Then, bit by bit, begin to see the office workers’ happiness as false. Doubt it all: Cho’s innocent gratitude, Gong’s spirited hospitality, and Gill’s constant subservient attitude. Intuit in all their actions a secret plan that goes against the love that Pe and Fi profess for them. And then something happens. It’s a thing that he no longer expects, and it takes him by surprise. It starts with an invitation: Cho, Gong, and Gill will make Mother and Father’s bed. Gruner is invited. They go into the master bedroom and, as a team, spread out the sheets and smooth the creases. And that’s how it happens, that something is revealed: Gong smiles and looks at Gill, and together, facing each other on either side of the bed, they each lift up a pillow and, before the surprised eyes of Gruner and Cho, spit onto the sheets before setting the pillows down again.

It’s the moment they’re rebelling and Gruner knows it—so much love couldn’t have been real. So he gathers his courage.

Gruner asks:

“Do any of you have change?”

All three seem surprised. Maybe it’s still too soon for the question, but then so too for the answer:

“Do you?”

Gruner says:

“Do you think I’d be here if I did?”

And they:

“Would we?”

During a long silence, they all seem to draw conclusions that merge, and start to formulate a plan that, though still undefined, now unites them in a newfound but sincere kinship. As if the action could hide the words they’ve uttered, Gill shyly straightens the sheets on a bed that is already smooth. And that night, when the euphoric familial love is reborn, Gruner understands that it has always been part of a farce that began many years before he arrived. And now nothing keeps him from enjoying Pe’s educational advice or the tender kisses Fi plants on her men’s foreheads when they say goodnight and go to bed. In the morning he submits gladly to the everyday activity, and at night, when doubt invades him and he starts to reconsider the plan as a bold tactic born of his own self-delusion, he realizes that the noises bothering him are really the light little taps of someone at his door. Taps that, like passwords to be deciphered, prompt him to get up, open the door, and find an anxious Cho. Under orders from Gong, he’s come to bring Gruner to their first meeting.

The gathering is in the public bathroom next to the ticket window. Gill, ever efficient, has covered the broken windows with cardboard so the cold doesn’t seep in, and he’s brought candles and snacks. It’s all set out on a tablecloth spread neatly over the floor in the middle of the bathroom. Sitting cross-legged, attentive like true office workers, the four of them settle around the tablecloth and pool their money in Gong’s hand. Four bills, large and crisp. It’s strange for Gruner to discover a new expression on his companions’ childish faces, a mixture of anxiety and distrust. Maybe it’s been months, maybe years they’ve been here; maybe they suspect that they’ve lost everything back in the capital. Wives, children, jobs, homes, everything they had before being stranded in a station like this one. Gill’s eyes grow damp, and a tear falls onto the tablecloth. Cho pats Gill on the back a few times and lets him lean against his shoulder. Then Gong looks at Gruner; they know Gill and Cho are weak, that they’re worn out and no longer believe in the possibility of escape, but only in the pitiful consolation of more days in the country. Gong and Gruner, who are strong, will have to fight for all four of them. An unsparing plan, thinks Gruner, and in Gong’s eyes he finds an ally who follows every one of his thoughts with attention. Gill goes on crying, and he wails:

“With all this money we could buy part of the land, we could at least live independently …”

“The train has to stop,” resolves Gong, with a seriousness unseen in him before.

“What do you want to do?” asks Gruner. “How do you stop a train? We have to be realistic here. Objectivity is the foundation of any good plan.”

“Tell us, Gruner—why do you think the train doesn’t stop?” asks Gong.

And Cho replies anxiously:

“It’s because of Pe; he signals that there are no passengers.”

“We know the signal for ‘Don’t stop.’ What we don’t know is the signal for ‘Do stop,’ ” says Gong.

“I see,” says Gruner. And then, illuminated: “And did you already try the negative?”

“The negative?” asks Gong.

“If the signal means ‘Don’t stop,’ ” says Gruner, “the negative is …?”

“No signal!” cries Cho.

“We’ll have to pray,” says Gruner.

“We’ll have to pray,” repeats Gill, wiping his eyes with a paper napkin.

It all happens just as it should, as they’d set out in the plan. First of all, dawn breaks. Fi pokes her head through the kitchen door and calls the family to breakfast. The office workers, each one back in his room, put socks on their feet, jackets over their pajamas, slippers on their stockinged feet. Pe is the first to use the bathroom and the others wait to follow in order of their arrival: Gong, Gill, Cho, and finally Gruner, who, because he knows he’s last, uses the time to feed the dog, by then already sitting near the door. Fi greets them all and hurries them along so breakfast doesn’t get cold. Then Cho distracts Fi, bringing her over to the window and pointing to something in the fields, maybe an animal that could be that day’s lunch or dinner. Meanwhile, Gong watches the bathroom door to be sure Pe doesn’t come out; after all, he is next in line and it’s not strange for him to wait outside. And that’s when Gruner and Gill dissolve the sleeping pills stolen from Fi’s nightstand into Pe’s big mug of coffee. Once they’re all sitting around the table and the breakfast ceremony can begin, the office workers do nothing but watch Pe’s mug. But Pe and Fi are focused on that first meal of the day, and neither of them notices their stares. Considering the delicacies they heap onto their plates, the office workers themselves seem to have forgotten the matter. When they finish, Gill clears the table and Cho washes the dishes. Gong and Gruner declare that they’re going to straighten up the rooms and make the beds, and under Fi’s permissive smile they withdraw.

They’d agreed that all four would meet in Gruner’s room after they’d pulled off the first part of the plan. Once there, the office workers—or rather, Gill and Cho, not Gong and Gruner—find themselves nostalgic. Gill believes that, after all, Fi has been like his mother, and Cho admits that he has learned a lot about country living from the hand of a man like Pe. The hours of teamwork and the family breakfasts won’t be easily forgotten. Gong and Gruner keep moving as these ruminations take place: They pack some bags with a few little souvenirs, some small stones and other things Gill and Cho have collected, plus some apples to eat on the train.

Then Gong’s watch alarm goes off: It’s time. The train will be here soon, because this is the exact moment when, every day, Pe gets up from the sofa where he does his morning reading and walks to the field to stand beside the tracks and signal. Gruner gets to his feet, and so does Gong, and now everything is in their hands. Gill and Cho will wait on the station bench. In the living room they find Pe asleep on his sofa. They try strong, loud words: “Chomp!” “Attention!” “Scrutinize!” But Pe, sunk into the deep sleep the sedatives have induced, doesn’t wake up. Gill kisses him on the forehead and Cho imitates him; there are farewell tears in his eyes. Gong makes sure that Fi is in the backyard watering her plants like every morning, and there she is. “Perfect,” they say to one another, and finally they all leave the house. Gill and Cho go toward the station, Gong and Gruner toward the field, walking along the tracks toward the train. They spot smoke on the horizon from a train they still can’t see, but that can already be heard.

After several steps, Gong stops. Gruner is supposed to go on alone—it takes only one man for the non-signal. Gong slaps him on the back a few times, and then Gruner keeps walking. It’s going to be hard to see the train approach and want it to stop, and count only on the non-signal. To stand by the tracks and do nothing, to just pray, as Gill said, because maybe that’s the signal for God to stop the train.

The train comes closer, moving along the tracks that cross the countryside from one horizon to the other. And soon it’s at the station. Gruner focuses. He stays as still as possible, and when the train passes him, it’s hard for him to tell whether it’s making the sound of a train that’s speeding up or of one that’s going to stop. Then he moves his eyes down toward the wheels turning along the tracks, and he notices that the iron arms that push them along are starting to slow their movement. He doesn’t see Gong, doesn’t know where he is, but he hears his shouts of joy. The train moves past Gruner and, finally, comes to a complete stop in the station. He watches triumphantly as the platform begins to fill up with passengers, and he realizes that, underneath the clamor of people, Gong’s cries are directed at him: He is very far from the station, the distance is long, and the train’s whistle is already announcing its departure. Gruner starts to run.

At the station, in order to board the train, Gill and Cho have to push through dozens and dozens of passengers who are still disembarking. People and luggage are everywhere. The same words are repeated like an echo along the length of the whole train platform:

“I thought we’d never get off.”

“Years, years, I’ve been on this train, but today, at last …”

“I don’t even remember the town anymore, and now, suddenly, we’re here …”

People shout and cheer; there’s almost no more room in the station. Then there’s another whistle, and the sound of the train as it starts to move off. Gruner is almost there. He sees Gong, who is waiting at the end of the platform and helps him up. A group of men who have unpacked their instruments play a happy tune to celebrate the occasion. Gong and Gruner move among children, men, and women, and before they can reach the first door, the train is already moving alongside them. That’s when Gruner sees, among jubilant ex-passengers, the thin, gray figure of the dog.

“Gruner!” yells Gong, who has now reached the first door.

“I’m not going without the dog,” declares Gruner, and as if those words gave him the strength he needed, he goes back to the animal and picks him up. The dog lets him do it, and his terrified face goes with Gruner as he dodges the euphoric bodies. They reach the train’s last car and pull even with it. Gruner senses that from one of the windows Gill and Cho are watching him in anguish, and he knows he can’t fail them. He grabs hold of the back stairs of the train and the thrust of the machine plucks him from the platform, as though from a memory in which his feet had recently been planted, but that now grows smaller and disappears in the countryside.

The back door of the car opens and Gong helps Gruner up. Inside, Gill and Cho take the dog and congratulate Gruner. The four—now five—of them are there, and they’re saved. But, and there is always a but, in the door there is a window, and from that window they can still make out their station. A station full of happy people, overflowing with office supplies and probably also with change. It’s a station that for them has been a place of bitterness and fear and that nevertheless now, they imagine, is something like the happy civilization of the capital. A final feeling, shared by all, is of dread: the sense that, when they reach their destination, there will be nothing left.

This story, translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell, appears in Mouthful of Birds, published by Riverhead.