Simo Häyhä, whose life this story imaginatively elaborates on, was a renowned sniper during the Winter War between Finland and the Soviet Union. The fighting, which began in November 1939 and ended in a Russian victory in mid-March, was fiercest along Finland’s eastern border, in Karelia.

Distance

“Do you see?” my father said.

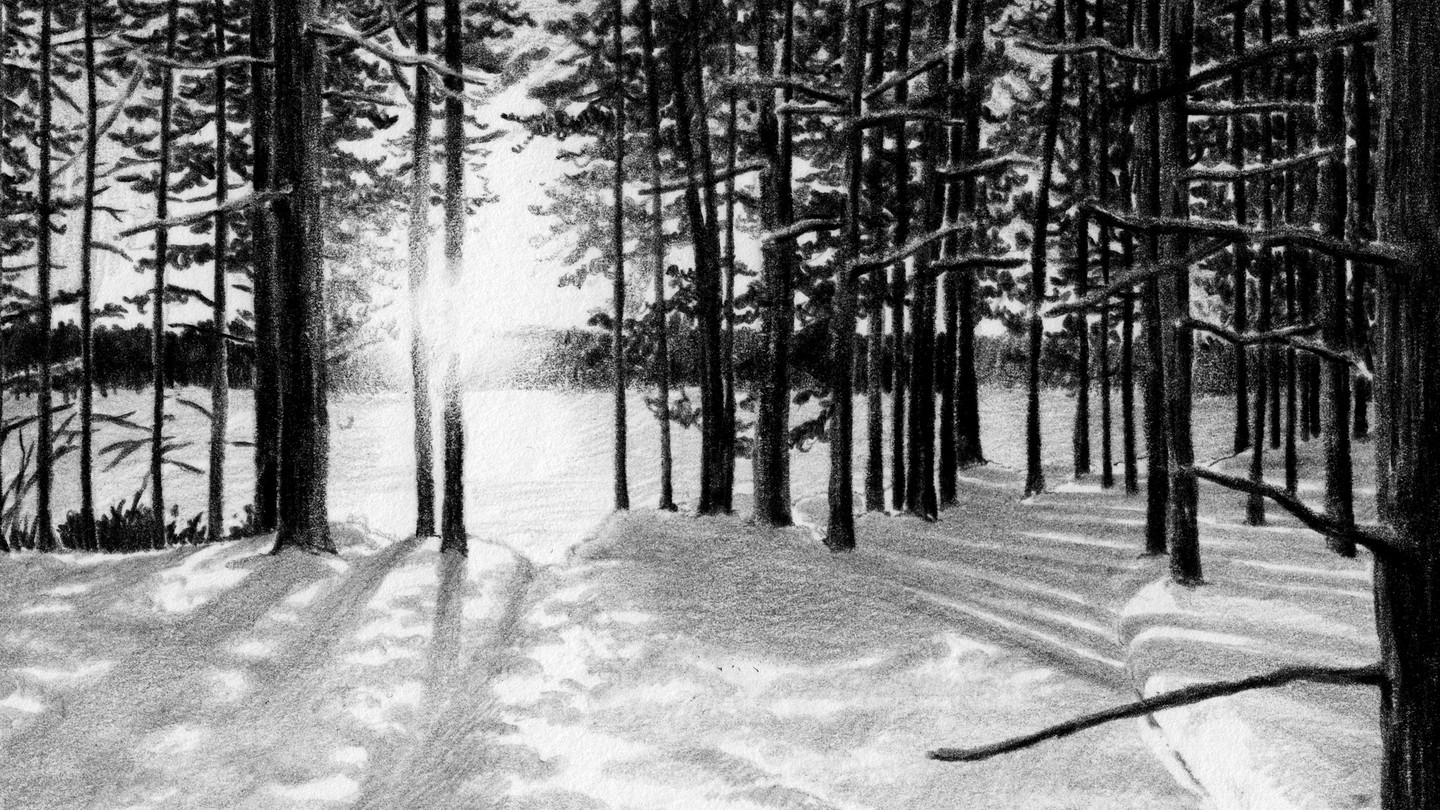

I breathed in and out, the air shallow in my chest. I was 10. On the way back from his dawn hunt, my father had sliced the tip off a reindeer antler and placed it somewhere in the array of space and field behind our cabin. My job was to find it. We were on our stomachs in the snow, under the stand of trees where, in summer, our horse Teemu lowered his gray face in the shade. We’d been here for two hours, waiting while I looked and looked for the tip, which would be our target.

“Yes?” my father said.

I nodded.

“Where?”

“The fang,” I said. This was the shattered birch trunk that had split the year before last in a storm and now stood, jagged and lonely, at the edge of the far field. “Well, five steps before it.”

“How far from our position?” he said. He would aim only and exactly as I instructed. Such was his test.

“One hundred forty-eight meters,” I said.

My father turned his round, dull eyes to me. “You’re sure?”

I nodded.

“Go mark it, then,” he said, and moved the rifle from where it lay between us.

Progress was slow in the snow. As I approached the fang, the sun hit the ice covering the old silver wood and made it sharp with light. I turned and faced the place I knew my father was, though you’d never be able to see him, not if you looked for a whole month. I counted five steps back toward him and stopped.

The shot rang like a bell in the frozen clearing that pocketed the cabin and the shed and our two fields. The spray of ice shards hit my face so hard that I fell backwards, and I stared at the place where the bullet had obliterated the tiny piece of antler, poking maybe five centimeters above the snow, just between my feet. If I’d said 149 meters, or taken six steps instead of five, my father’s round would’ve passed through my stomach.

When I got back to the cabin, he was already inside, the rifle half-disassembled.

“One hundred forty-eight meters,” he said, and glanced at me before going back to wiping the bolt, which was as close as he ever got to good cheer. Then he said what he always said. “You’re only wrong once, Simuna.”

The White Death

The Russians, as was their wont, had their own name for me, the White Death. My men called me the Magic Shooter, which I also hated. I am Simo Häyhä, corporal of the Sixth Battalion, Regiment 34; previously of Bicycle Battalions 1 (Third Company) and 2 (First Company); previously of the Civil Guard volunteers, all in service to the glorious and proud Finnish cause. Or I was, anyway, until 1940, when everything (we thought) was over and it turned out I was in fact still alive, and someone decided to make me a second lieutenant for it.

I’ve liked only two nicknames in my entire life. My father and mother both called me Simuna, which means “God has listened,” though I suspect what they each imagined he heard was different. It was M, though, who first called me Kettuseni, “my little fox.” When I think of those 98 days in the forest, I hear only that name. When I dream of M now, I wake myself sometimes, the sound of it floating around the room, before I understand that my own lips uttered it.

Our regiment commander, Lieutenant Juutilainen, was known far and wide as the Terror of Morocco, due to his time there with the French Foreign Legion, fighting the Berbers in the Atlas Mountains. We ourselves called him Papa. He was a quiet man with a sad, clownish face who spent most of his time drinking in his officer’s tent, where it was warmest and where he let me sleep between my hunts. This was more or less how he’d spent his time in the Atlases too, I gathered: drinking to stay warm in the frigid air, then venturing out for a whole day of stalking the slopes with his rifle and skis. By the time the Soviets shelled Mainila, though, his flurries of activity took place in the command tent. When the Russians began pouring toward our lines, and Major General Hägglund asked his famous question, I myself watched as Papa gave his famous response: “Yes, Kollaa holds. Unless our orders are to run away.”

Once, two days after Christmas, we managed to capture a sorry Russian who’d gotten lost and wandered almost right into our camp. He didn’t even have a weapon. We blindfolded him, spun him around until he was so dizzy that he could barely stand, then marched him in circles, telling him the whole time that we were taking him to the Terror of Morocco. By the time we brought him into the tent and took off his blindfold, he was shaking with fear and Papa insisted we drink with him all night. Whether thanks to the spirits or our company, he came back to life in front of us. Before dawn we marched him off toward his own lines, pointed him where to go, and set him loose. He cried the whole way, begging to stay. A month later, when we retook those woods, M told me he found the man, frozen stiff, propped against a tree where his own officer had shot him in the forehead for deserting.

The Zero

I was born the last of four brothers, too young to join them in the civil war when it came in early 1918. Antti was shot through the nasal cavity by a Red Guard marksman on a drizzly evening in Tampere. Juhana was wounded in the close fighting at Joutseno, and taken prisoner. By that time, the Reds had heard about the prison camp and mass grave at Kalevankangas.

I was 12. Spring brought the German Imperials to the streets of Helsinki and the Whites to Vyborg, victorious. In May, the Whites took Fort Ino, near the Neva Bay, on the Karelian Isthmus. The war was over, and finally Juhana was returned to us. The power of speech had deserted him, and we were all left to imagine exactly what had driven it away. He was only good for fieldwork by then.

Summer came, and Mother sang Tuomas and me psalms in the evening while she mended our clothes. Antti was gone, Juhana was just beginning to work again, and I was needed around the farm to help Father with the timber, so it was Tuomas who was sent to the road project at Miettilä to work. The summer was brutal, and each time Tuomas returned from the work site on the weekends, he looked more shrunken and sallow. The foreman himself came all the way out to the farm to tell my father about the afternoon, the hottest anyone could remember—about the way Tuomas had straightened up as if someone had called his name, before crumpling to the ground with sunstroke. Then he was gone too.

That winter, during the few hours of morning light, my father set a single bullet upright on the table in front of me, before sending me out with my rifle. I carried the round inside my glove as I walked, and felt the brass get hot and slick in my palm. If you can’t do it with one, I’d heard him tell Antti, you can’t do it with two. In the first week, I missed my shot two days in a row, and each night my father made me sit at the table as everyone else ate potatoes from the cellar, my plate empty in front of me. My father wouldn’t look at me. My mother wouldn’t look at him.

On the third day, hunger had sharpened my senses. I disappeared into the woods; time disappeared into the day. I came back in the dark with two hares. I’d waited, lying alongside a log, until they passed one in front of the other. My father met me on the porch, and pulled me into an embrace so rough I thought at first he was wrestling me. I could smell the cold and the forest on the stiff hide of his overcoat. Then he took me by the shoulders and held me away from him so that he could look into my face. He took a breath as if to tell me something, but said nothing. I did not miss again.

I always kept my rifle zeroed at 150 meters. If you can’t get within 150 meters of a kill, my father used to say, you don’t deserve to make it. The same was true 20 years later, in those frozen woods with M. Whenever there was a lull, I found a dwarf pine on a slope and watched the top of it disappear in a puff of snow. You could tell when you’d missed or just hit the ice, instead of the trunk. I never missed.

Rolling Hell

M came wheeling around the bend on his bicycle, singing. This was the first time I ever met him. He was reporting for the marksman training camp. We’d been paired together, and I was sitting on the firing platform with the other shooters, waiting for the spotters. M could be almost as silent as me when he wanted, but this was just before the war, and he sang at the top of his lungs. He had a deep, dark river of a voice, and even then I closed my eyes and let it wash over me.

When we were in position for the first drill, I patiently waited for him to give the usual range, wind condition, firing pattern, etc. But he didn’t. Instead he lay on his back with his head against the sandbag and closed his eyes to the sun.

“Aren’t you going to inform me?” I said to him.

He spoke without opening his eyes.

“No,” he said.

“You’re not?” I said.

He shrugged.

“I know who you are,” he said.

I blew air between my teeth, exasperated. I thought he was impudent.

“Do you need me to tell you?” he said.

“No,” I said.

He tipped his cap over his face.

“Range?” I said. I couldn’t believe his impertinence, his laziness.

M only sighed, and didn’t move.

“Range 1-9-2 meters,” I said, testing him.

“Don’t be silly,” he said. “It’s unbecoming.”

“Range 2-1-1 meters,” I said.

“Correct,” he said. “Doesn’t that feel better?”

We were silent. I went through my routine and waited so long that I thought for sure he’d fallen asleep. I fired my first round at the target.

“Hit,” M said quietly, as if to himself.

“You didn’t even look,” I said.

“I listened,” he said.

Later in our training, when new groups would arrive at the camp, they’d ask who he and I were. All the other marksman teams had taken up code names by then to confuse the Russians. Silent Doom. Death From the Trees. That sort of thing. M and I refused. Soon enough everyone would have a name for me anyway. But when the new recruits would arrive and see M and me returning from the supply depot, singing together on our bicycles, weaving over the ruts, laughing and gamboling like two fawns, they’d sneer, “And what are you, oh fearsome brothers?”

And M would put his arm around my shoulders and grin.

“Oh, us?” he’d say, a crown of daffodils chained around his hat. “We’re Rolling Hell.”

Winter began, and the big cogs of the world around us turned toward war. We were to have one last break before heading to the front. Many of the men went home. M and I both loved the forest and decided instead to go hiking for all four days. He’d spent a lot of time out there as a child and told me he knew an unmarked path.

The first day he drove us hard, casting a look back at me only occasionally to see whether I was keeping up. He barely spoke to me, and my heart began to feel like a sharp piece of steel. I imagined a firing mechanism exploding from a homemade round—the jagged pieces of barrel and stock. It began snowing as we pitched our tent, and though I was exhausted, I lay awake in the dark.

The next morning was clear and bright. M took my hand and led me out to the middle of the frozen lake we’d camped beside in the night. The snowfall had turned it into a pure white field.

“Well?” I said. I wanted to go home. I felt embarrassed.

But M’s face was bright, happy, flashing with something. He dropped to his knees and made big sweeping motions with his arms, clearing the surface of the ice.

I thought I was dreaming. Suddenly we were standing on air. On ice so perfectly clear, it might have been air. Fifty feet below, I could see the algae on the stones at the bottom of the lake.

“It only happens when the water freezes very, very slowly,” M said. “The winter has to be so patient, and then one day there it is, a miracle.” He looked at me, letting out his breath. “I thought you’d like that.”

Later, of course, I would come to know well the scent of him—rich soil and tobacco and sweat—carried under his snow cape and coat and uniform. His taste. The rough scratch of his stubble and its delicious burn. But when we were out in the silent hours upon hours of our hunts, when we lay behind an embankment and waited for the first suggestion of dawn, breathing slowly and evenly to reduce moisture plumes and to lower our body temperatures, I thought only of that morning. Laughing and falling on each other. Shuffling around in the impossible clarity of that place.

Distance

The winter makes everything itself, I told M the day we found the black wall of bodies. He’d spent a lot of time in the brush as a child, it was true, but the rest of the time he lived in the city, and at first he didn’t understand what we were looking at. We’d heard there’d been heavy fighting right away, but there were few roads in our area, and the Russians quickly found themselves stalled in pockets of the forest as we crept around them.

The clearing—a meadow in summer—was dim and quiet. Our boys had set up their machine-gun positions among the trees, where they would have clear lines of fire but couldn’t be spotted. The Russians had made their camp in the middle of the open space, for who knew what reason. This was at the beginning. We didn’t yet know how unprepared they were to fight. Some didn’t even have winter clothes. Only the officers had real tents. The rest made do with improvised shelters, anywhere they could hover around their tiny fires, a tidy constellation of targets.

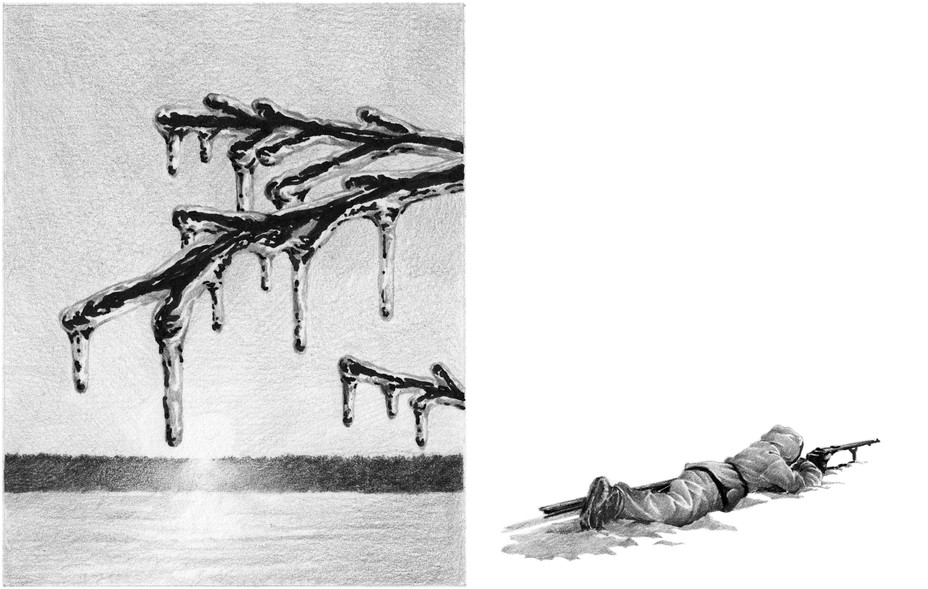

At whatever cue, they’d been ordered to charge out toward the trees, where the men were felled, one atop another, by the machine guns. That winter was so cold—colder than any of us had ever seen. So cold that the blood from the newest layers of bodies turned black and froze over the bodies stacked at the bottom. There wasn’t much snowfall, and the blackened wall of blood and bodies seemed orderly in the half-light of the day. M and I stood and looked at it for a long time.

The world is never very big. A map is just a piece of paper. My Karelia was just a corridor of wild land north of the vast waters of Lake Ladoga. You could be at the shore in a day on foot if you wanted. You could be at my father’s cabin in four. That day in the clearing we were something like 200 kilometers from the center of Leningrad, imagine. But the forest is endless. The winter stopped everything with its cold, even space.

Near the end, in our last week of war, only a few days before I was shot, we passed back through this clearing—a rare thing in a place where you could never trace the same path twice, even with careful planning. We were retreating, everyone could see it was over, and things were bad. I’d gone on my last hunt days before. Some of our fleeing units in their bitterness had hauled even more frozen Russian bodies out of the woods and propped them upright, their arms stilled in various eerie semaphore. The idea was to disturb the Russians before they overran us. Those corpses were black too, and they made the clearing look like the stunted remains of a wildfire. They were all facing the black wall and looked strangely as though they were trying to join their friends. My father used to say, If you need a map to know where you are, you’re already lost. Both times we passed through the clearing we paused. Then we kept going.

That first time, as we reentered the forest, M nodded to the horizon, where the sun was lurking, as high as it would get that day, a thin, golden-red line of color.

“The sky is burning,” he said. “What a waste.”

The Hunt

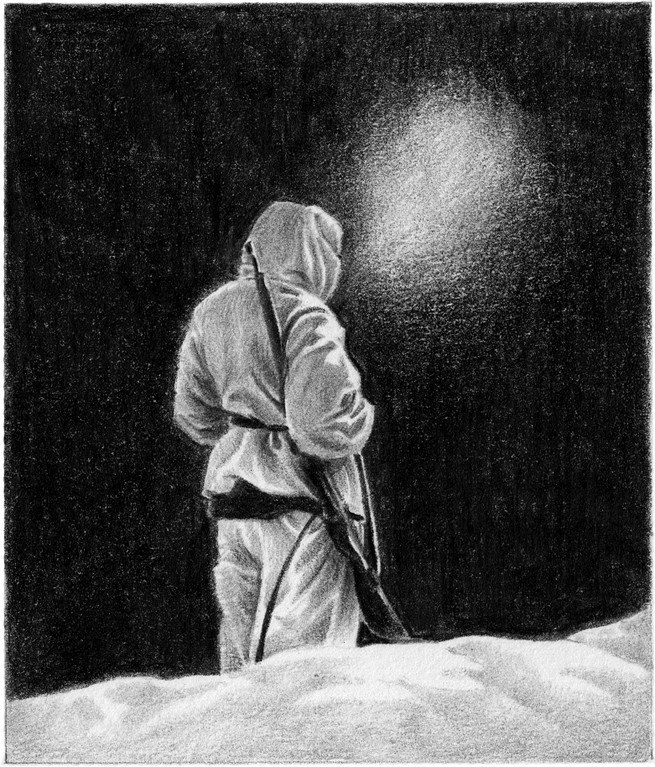

It was so cold that if your eyes got too close to the holes of the mask, your corneas froze. So cold that you needed a body within your body. Papa measured the temperature by planting one of his bottles in the snowbank outside his tent: If the alcohol turned to slush it was about –25 Celsius or below. At those temperatures, nobody moved but us. M and I would sleep through the few hours of weak light, then rise and head out as the forest gathered the darkness. Once we’d found a Russian camp, we would sit and wait until we were part of the stillness. Then I’d pick a position.

We’d urinate on the berm of snow, letting it freeze so the muzzle flash wouldn’t kick up any powder for the Russians to see. If we could make a snow cave or small space under the eaves of a tree, we would, and I’d sit there and watch the woods in front of us while M slept or lay there staring up at nothing, waiting. We’d trained ourselves to breathe slowly and carefully, keeping the moisture in the mask. Otherwise our breath would billow out and become a solid thing in the air.

It wasn’t hard to see the Russians. We were always close, 150 meters or less. They tried to make their camps where they could take cover behind low piles of deadfall or snow or whatever they could find. To make a perfect shot, you have to know every bit of the woods around you. You have to disappear into the air, to become the weight of the hard rime making the trees into statues.

Then it would be time. M watched me take off my outer gloves—knit—which I placed under the barrel to smooth the recoil. Then he watched me take off my mask. I put snow in my mouth to keep my breath invisible. I had about 10 minutes before the flesh of my face would freeze. I’d nod to M and we’d both face the target field.

A scope isn’t the world, my father said on my last trip home before I went to war. What do you see through a scope? Nothing. A picture. So I used the iron sights, as I had since I was a child. What do you see down the iron sights? Everything, as it is. The minuscule area of pale color that was a Russian face. The solid dark of a Russian’s torso. I fired and the shapes fell with small mists spraying out behind. The first shot was confusion for them, the second brought shouting, the third panic. Then a kind of stillness as they waited to see whether the cover they’d found would be enough to save them. Another mad scramble after the fourth shot. Then a wait, the skin of my own face losing feeling. A minute of quiet. Then a sliver of head, or movement; a ventured look out to try to see. The fifth shot always occasioned the strangest of the reactions. Once in a while a man cried. Twice a Russian bellowed with terror and madness. But I was already back behind the berm, in my mask, breathing, not even hurrying to refill my magazine. I was never spotted. I didn’t have a body. The forest was my body. My rounds came from anywhere. The men looked and saw only whiteness.

A long wait, stillness, silence. The Russians tended to their casualties, believing I’d fled. I’d wait impossibly long, until the few hours of daylight began to wane. And then in that frozen twilight, we’d repeat the process. Then we’d wait even longer before we crawled away. By the time we returned to our camp and stepped into Papa’s tent, the frozen creases of our furs under our snow capes would be sharp as knives. We’d sip warm soup from his stove and M would record the kills in the captain’s little book. Then Papa would go out to stalk the camp’s perimeter, and sleep would come like a coup de grâce.

Many years afterward, during a fox hunt led by the president of Finland himself, he requested that I show the group some of my firing positions. It was autumn then, 1970, and a different universe of trees and leaves and fallen logs.

“Is this what you remember?” the president asked, crouching and looking down my rifle with me. “What did it feel like? How did you wait for so long?”

M’s eyes were all that were visible of him as we both lay back under the tree or against the berm, buried together in the snow. The solid feel of his body there beside me. We had whole conversations made of just the wind, a sideways movement of iris that seemed to catch what little light there was. Between magazines, M would stay awake, watching to see whether the Russians would send a patrol out to find our position, and I would gaze up at him and think, Look at me. Look at me.

Wolves of Karelia

The wolves ate well that first spring after the fighting, and the next spring, and the next, it’s true. For 10 years after the war, their population grew uncontrollably, and packs traveled all the way to the farm. I had returned; it was just me and my father by then.

He insisted on hunting, though he’d grown old and slow. I would sit on the roof of the cabin and watch him coming home, sometimes with a kill, sometimes not. In either case, the wolves would be following at a careful distance. I’d see them coalesce into being out of the shadows of the trees. They did not, as far as I know, ever attack, though they easily could have. Still, they did follow him every day, at their distance, waiting for him to fall. My father never hunted wolves. He thought it disrespectful.

The wolves scattered the bones, starting that first spring, their faces perpetually crimson with the offal of the corpses. In later years, when I’d go out hunting again, I’d find a bone here and there: a jagged femur, the marrow sucked out; the little puzzle of a vertebra, so weathered and so cold that if you found it midwinter, it would shatter at the touch of a boot’s toe.

On the day my father didn’t come back from his hunt, I went out to find him. He wasn’t hard to track and hadn’t gotten very far. I shot every wolf I saw on my way to retrieve his body. Instead of dragging and cleaning the carcasses, I just left them there to mark his trail—a long, loose corridor of the dead. As soon as he was buried, I found an apartment in the city on a rise that looked out over the lake. The forest looked small and still from there, nothing really to see. I hunted only foxes after that.

“Five hundred and forty-two confirmed kills,” the occasional reporter says now, when one comes to visit. “What does that feel like?”

“Only 259 were with the rifle,” I tell them. “The rest were submachine. I don’t know how they counted those.”

“Still,” they press. “Do you ever think of it?”

I don’t, really, to tell the truth. Not that I tell them that, or much of anything. I do dream of the wolves sometimes, though. I see them just as I fall asleep. I’m standing alone outside the cabin, and they fill every gap across the field, where the forest begins. None of us moves, and I know they are waiting for me.

The 98th Day

Running. Our breathing the only sound in the woods. It was the first week of March. In February, the Russians had run out of patience. They poured half a million troops onto the isthmus, 3,000 tanks, 1,300 aircraft. We were maybe 75,000 men in total. M and I had decided to go on one last hunt but had not gone far before we heard and then saw the dark wave, streaming like water toward us from every direction. So we ran back to our men.

In front of us, our unit’s trench appeared and the men were yelling and we were leaping over the embankment and turning to fire, as was everyone else. Then the Russians were upon us. Flesh came apart around us. I looked to M as he reloaded and I watched a round tear through his torso sideways, taking him to the ground, just like that. I’d only just turned to fire when suddenly I was on the ground too. I felt something hot and wet in my mouth before I lost consciousness.

An explosive bullet had torn through the left side of my jaw, I found out later. Illegal, even in war, but the Russians were desperate, and had half-convinced themselves we were invisible, ghosts, immortal. I’m told I was dragged to the rear in the retreat—they tried to save me even though, as one of the men put it, half my face was gone. I’m told I was thrown on a pile of the dead before someone heard me gurgling and got me to the medics. My coma lasted seven days.

I woke on the day the armistice was signed, giving Russia our Karelia and everything else it wanted. It was March 12, 1940. We thought we’d seen the end of war. It was three years before I recovered enough to go out in public. Still, I tried not to. I stayed on the farm. People who saw me looked away, their faces rippling with nausea. Even now, at night, it still looks as if the darkness is pulling at the edge of my face, leaving a jagged edge of skin and flesh—as if I’m already half-gone.

The Heart Hunts Alone

I found M in a military hospital. He was still there, three years after we were shot, in the city. He was what they called then a “permanent,” having survived but with lungs that needed to be drained often enough that the doctors believed he’d be there forever.

I sat in the chair by his bed. It was summer and the sheets were very white. He was almost unrecognizable, a heavy beard turning his eyes sharp and dark.

“You’ve grown a beard,” I said. “I just grow shrapnel.”

Which was true. I felt the burning itch of it as the flesh and skin worked the bits to the surface, where they’d fall into the washbasin, trailing a tiny ribbon of blood.

He looked not at me, but at the ceiling.

“The Terror made it through,” he said. “Can you believe that?”

I looked at my hands and nodded.

“Terror always does,” I said.

“Can you believe they gave away Vyborg?” M said, as if it had just happened.

A nurse came by to check something, and we sat quietly until she was gone.

“I might live in the city now,” I said. “I might get an apartment.”

M didn’t say anything.

“Let me take you home,” I said. “I will bring you back for the treatments, easy enough.”

M turned on his side away from me. I could see his jaw held tightly.

I’d forgotten, somehow, what I looked like. How monstrous. The slurred sound of my voice. What was the difference, really, between my presence and an awful dream?

I thought I couldn’t touch him, because of all the dressings.

Life Without End

That’s the hymn they sing in the chapel of the little town where I live now. I hear it on Sunday mornings in the winter, the soft timbre of the muted voices sliding down the streets on the ice.

I ran into M once more, years and years later. It was 1979 by then. He’d made it out of the military hospital after all, it turned out. We’d both moved to this same town, unknowingly. We stopped and had coffee, and stayed in the café all afternoon, talking and laughing about the men we used to know, the strange and funny things that had happened sometimes in the woods. He did impressions of the doctors who’d come and gone, and I did too. He explained that there had eventually been a surgery for his lungs, and he’d been freed.

“You know, I loved the war, actually,” he said finally, looking at his mug. “But only when I was with you.”

We agreed we should have dinner soon, maybe see a film, and went our separate ways. That was the last time I ever saw him. Eventually I heard he’d moved, and 12 years after that I saw by chance in the paper that he’d died, alone in a veterans’ home.

“You’ll live forever!” my doctor said to me at my last checkup, laughing. “We should all be so lucky!”

Each year, the morning after the first brutal freeze of the winter, I drive all the way back to where the farm was and go into the forest. I take my rifle but no rounds, not wanting to disturb the silence. Not that I could disappear again into anything, old man that I am. And what does it all come to, such a life? My father cuffing the back of my head gently as I brought in firewood. The Terror of Morocco, drunk, dancing in his long underwear on Christmas. The yellow of M’s daisy-chained crown as he held it in his teeth. The clear sun slanting down as we stood on air and spun, laughing and laughing.

I’m a coward, in the end. I always come back out of the woods to the car. I always drive back through the darkness, into another evening, another morning, another evening. I can’t even say how it felt, M’s solid warmth beside me in the forest as we waited for the light to begin. I can’t even say his name.