Elvis Reenters the Building

In rural Ohio, a performer bookends a year of struggle and survival.

This article was published online on May 7, 2021.

Strict guidelines had been announced before the show: There could be no kisses on his cheek, no holding of his hand, no accepting of his garish, sweat-drenched scarves. In short: There could be no physical contact with Elvis. But the King was caught up in the moment, playing by his own rules. He had been waiting a year for this. And so had Sue Paszke, although for her it had felt much longer.

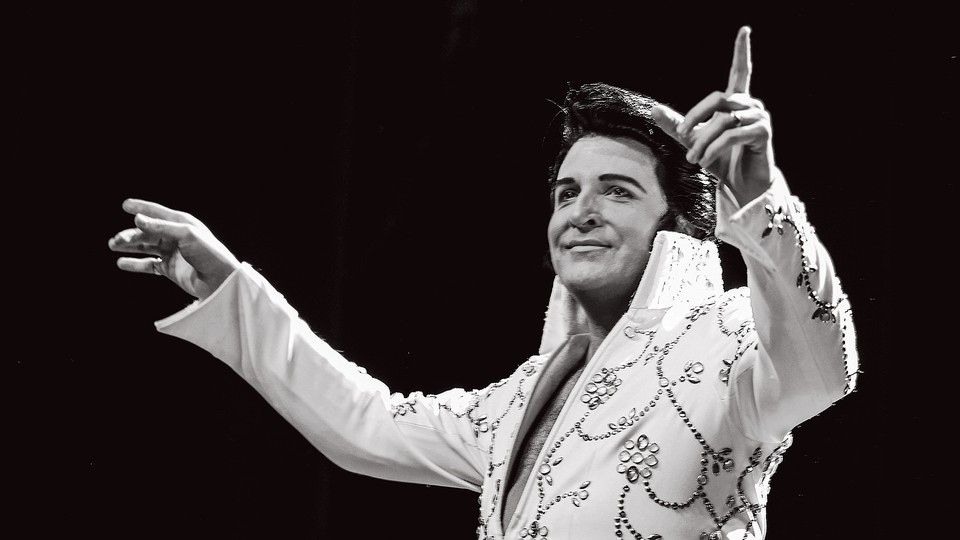

The last time Paszke and her fellow “Blue Hawaii Ladies” had caught a live glimpse of Dwight Icenhower—one of the world’s foremost Elvis “tribute artists”—was on March 7, 2020. It had happened here, inside Stuart’s Opera House, an elegant concert hall tucked into the hollows of Appalachia, in Nelsonville, Ohio. For 20 years, the ladies—uniformly clad in sky-blue aloha shirts—had been Icenhower’s groupies, following him to shows all around the country. Paszke, a 78-year-old retired lunch lady from Columbus, had struck up a ritual with Icenhower: Every time she saw him perform, he autographed her favorite scarf. When Icenhower came to Stuart’s Opera House last March, he signed the scarf for the 99th time. Once more, Paszke joked, and she could die a happy woman.

And then she almost died an unhappy woman. Several months into the coronavirus pandemic, Paszke awoke in the middle of the night unable to breathe. Her husband rushed her to the emergency room. “Good news,” the doctors told her. “It’s pneumonia.” She was flattened for the next two months. Despite orders to avoid human contact—an infection being a likely death sentence—she couldn’t seem to stay out of the hospital. Having recently undergone surgery on one knee, she soon had the other knee operated on as well. Later, her heart rate began spiking uncontrollably, the result of a previously undiagnosed cardiac condition. She wept and wallowed and cursed her circumstances: too frail to attend funerals, too compromised to meet her first great-grandchild. “It was hell,” Paszke told me. “All I could do was wonder …” She paused. “I didn’t think I’d ever get that 100th autograph.”

One year and six days later, she stood in an elevated box on the right side of Stuart’s stage, a Juliet awaiting her Romeo. This was a special occasion—and not just for Paszke. It was a homecoming for Icenhower. (Yes, Dwight Icenhower is his real name.) Having grown up nearby, he had achieved some level of fame as Elvis reborn—he’d performed around the world and starred in a Super Bowl commercial for Apple that has 1.4 billion YouTube views. But the pandemic left him with considerable time to reflect on his life and career. When he talked with Stuart’s about headlining its first show upon reopening, he asked not to perform as Elvis Presley. He just wanted to be Dwight Icenhower from Pomeroy, Ohio.

He ditched the white jumpsuit and sunglasses for a mustard jacket and black skinny jeans, and performed not only Elvis’s greatest hits, but also a medley of Johnny Cash and Ricky Nelson and Elton John songs. When the time was right, he called out to Paszke. Her scarf had been sneaked backstage before the show for Icenhower’s signature. Now, telling the crowd their story, Icenhower took Paszke in one hand and raised the faux silk with the other. The moment was one part triumph of the human spirit, one part proof that beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

“I know it might sound weird—all this fuss over an Elvis tribute artist,” Betsy Naseman, Paszke’s niece and a fellow Blue Hawaii Lady, told me afterward. “But being back here a year later, it feels like we’ve come full circle. Like we’ve survived.”

Easily the youngest of the group at age 38—she joked that she’s their chaperone—Naseman works at a senior-care facility in Cincinnati. The past year, she said, “has been so devastating.” More than 20 of her residents died. And the one thing that could always lift her mood was no longer there. “I needed one of Dwight’s shows in ways I can’t really describe,” Naseman said. “We all need something, right? We all need that human connection. I didn’t have it. None of us did. And that’s not normal. That’s why today felt so good. It felt like normal again.”

Sitting nearby, Paszke stroked the scarf, tears welling in her eyes. “I wasn’t sure if I should come today. I felt a little guilty. I’ve only gotten the first vaccine shot, and so many people are still hurting,” she said. “But do you know what my doctor said? He told me I needed to come. He said it would be good for my soul. He said I need to get happy to get healthy.”

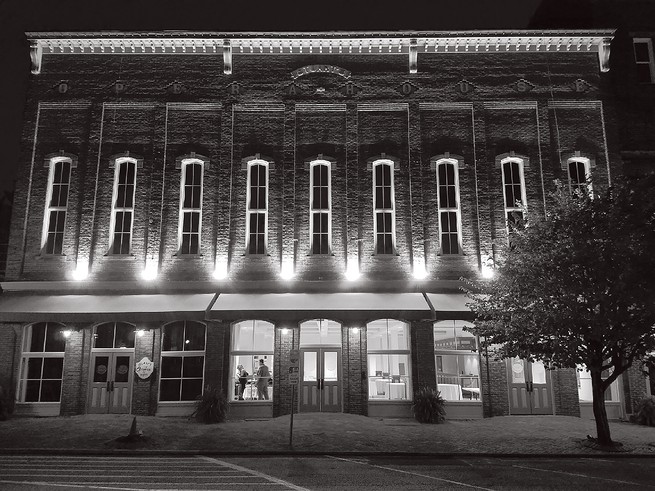

Presiding over the historic public square of Nelsonville, a city of some 5,000 people, Stuart’s Opera House is three stories of brick and nostalgia—a monument to a time when workers and families flocked to Appalachia, when an opera house could thrive in a small town because the locals were financially secure and starved for culture.

The venue opened in 1879, and what ensued is a story common to scores of opera houses around rural America: a couple of generations of prosperity, followed by sudden collapse.

More than 50 years after Stuart’s curtain fell in 1924—when the end of the coal-extraction rush coincided with the advent of mass cinema—a local group decided to revive the theater. But a fire in 1980 nearly destroyed the building. Rebuilding and reopening took 17 years. From 1997 to 2015, Stuart’s thrived as a cultural novelty in a region ravaged by the forces of deindustrialization and outsourcing and automation. And then the opera house nearly burned down—again.

“The story of this place is survival,” Melissa Wales, the theater’s executive director, told me as we walked its corridors. Tracing the brickwork backstage, I could see three lines of ceramic demarcation—masonry from the original opera house, from the rebuild after 1980, and from the rebuild after 2015. “This place has survived a lot,” Wales said. “And now it’s survived COVID.”

During my visit to Nelsonville, I heard that word—survived—over and over, from Naseman and the other Blue Hawaii Ladies, from Wales and her colleagues, from the bartender at the Mine Tavern next door. (“How’s business?” I asked. “We survived the worst,” he said.) The mood was less celebratory than quietly relieved, the joys of reopening and reconvening inextricable from the grief and trauma not yet fully behind us.

“My leg is shaking. I’m nervous. This is a huge, huge day for us,” Tim Peacock, the longtime artistic director at Stuart’s, told the crowd before Icenhower’s show. “Thank you all for coming.” Backstage, he’d guzzled Pabst Blue Ribbon as a tranquilizer. It all felt surreal. Twenty years at this venue, Peacock told me, couldn’t have prepared him for Elvis leaving the building last March. He’d worried that Stuart’s was finished.

“We were the first industry to get shut down, and we’re the last industry to reopen,” he said. “And honestly, this place couldn’t have survived without some very generous donations.”

Stuart’s booked Icenhower for the grand reopening in part because of his devoted—and elderly—following. (The older the crowd, the more vaccinated patrons.) Because Ohio’s governor had capped venue capacity at 15 percent, Stuart’s scheduled two shows. The performances could accommodate 60 people in a hall built for 395. But neither one sold out.

“Dwight’s been playing packed houses here for 10 years. So the fact we haven’t sold 60 tickets to either show—” Wales stopped herself. “It’s a bit alarming.”

Mary K. Walsh grew up in Nelsonville. “This square used to be very busy,” she told me, staring out the third-floor windows of the opera house. “You didn’t notice the decline at first. It was gradual, over a long period of time, until you turned around one day and there was nobody here.”

As a girl, Walsh had been enchanted by the abandoned opera house. She explored it with her father, who worked for the local electric company, which leased parts of the building. It wasn’t until she was grown and gone—living and working an hour away in Columbus—that Walsh began to realize the thing that might help to revitalize Nelsonville had been there her entire life. She bought a home down the road from where she’d grown up, joined Stuart’s board of directors, and in recent years has become its de facto historian. Nelsonville “is a different place with the opera house open,” Walsh said. “It really helped bring that sense of community back.”

It also delivered a needed economic jolt. When Stuart’s books a big act—and especially during its annual summer music festival—the area is transformed. Local shops see record sales. Bars and restaurants overflow. Airbnb rooms sell out. (There are no hotels in town.)

Still, the city’s long-term trajectory keeps bending south. Good-paying jobs are scarce. Opioid abuse is rampant. By every metric—rates of poverty, crime, income, education—Nelsonville is in crisis. This can be obscured when the Columbus Symphony Orchestra comes to town. But it cannot be ignored.

“It’s always bothered me,” Tim Peacock said after Icenhower’s second show, leaning against the lobby bar. “None of us who work here are from Nelsonville. None of us even live here. Meanwhile, the people down the street are looking at big potholes in the roads. They can’t afford new clothes for their kids. And they’re wondering how these people who commute into Nelsonville raised $4 million for a theater.”

“We’re the poorest county in Ohio—and that’s part of our success,” he added. “A lot of people come here because they want to go on a poverty tour. They want to go slumming in southeast Ohio.”

By all accounts, Stuart’s is a model citizen, hosting blood drives, free dinners, and music-education programs. The opera house even subsidized the hiring of a local school’s art teacher. But every year, Peacock said, the suffering around him becomes more glaring. As some of Stuart’s employees toasted to the reopening after the encore show, a certain unease filled the air. It’s good that the opera house survived. It’s good that out-of-towners who can afford concert tickets survived. But what about the folks who live blocks from the theater and have never been inside?

“I’ve barely been able to look people in the eye,” Jennifer L’Heureux, the owner of Nelsonville Emporium, a charming storefront across the square from the opera house, told me. She described the past year as a nightmare for the battered community. Her boutique, which sells locally made pottery and other goods, had grown to employ a staff of 12. “And then COVID destroyed everything. A shop that had been filled seven days a week, a shop that couldn’t keep up with its orders, was suddenly empty overnight. Completely lifeless.”

Bills stacked up. Federal assistance proved elusive. The prospect of firing workers haunted her, but L’Heureux feared that if she didn’t, the store would fold. Soon after letting her entire staff go, she fell and broke her ankle, requiring surgical reconstruction. The store, she announced, would close indefinitely. “People would see me around town and say, ‘It must feel good to have all this free time on your hands,’ ” L’Heureux recalled. “But it wasn’t free time. It was time spent wondering if I would make it.”

Then she got a request for a specialty order, and then another. Soon, despite her store being closed, she was fielding appointments for people to come in and browse. People started getting vaccinated. State restrictions began to loosen. And Stuart’s Opera House announced a show.

A few days after Dwight Icenhower thrilled Sue Paszke with a rendition of “I’ll Never Fall in Love Again,” L’Heureux told me she’d reached a conclusion: She, too, was going to survive.

This article appears in the June 2021 print edition with the headline “Elvis Reenters the Building.”