The Opportunists

In Louis Menand’s monumental new study of Cold War culture, success owes less to vision and purpose than to self-promotion.

This article was published online on May 5, 2021.

Louis Menand’s big new book on art, literature, music, and thought from 1945 to 1965 instills the conviction that the 20th century is well and truly over. It seems like the right gift for the graduating college senior this year. Born in 2000, the proud degree-holder may not recognize the Jackson Pollock reproduced on the accompanying Congratulations! card, or know the Allen Ginsberg lines misquoted in the commencement speech, but can look them up in The Free World: Art and Thought in the Cold War and confirm that this past is truly past. For those of us who lived through any portion of this period and its immediate aftermath, the book is a rather amazing compendium of the scholarly research, revision, and demythologizing that have been accomplished in recent decades. Interweaving post-1945 art history, literary history, and intellectual history, Menand provides a familiar outline; the picture he presents is one of cultural triumph backed by American wealth and aggressive foreign policy.

Menand’s inclination is not really to debunk, nor to make or undo reputations. Yet guided by a fascination with the wayward paths to fame, he half-unwittingly sows doubt about the justice of the American rise to artistic leadership in the postwar era. In his erudite account, artistic success owes little to vision and purpose, more to self-promotion, but most to unanticipated adoption by bigger systems with other aims, principally oriented toward money, political advantage, or commercial churn. For the greatness and inevitability of artistic consecration, Menand substitutes the arbitrary confluences of forces at any given moment.

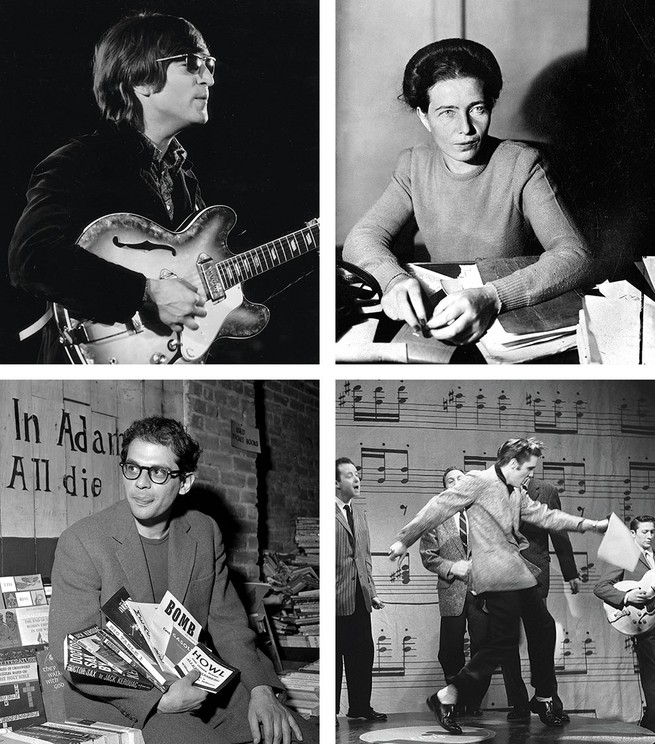

The book is constructed as a “great books” program of personalities, glued together by middlemen, all contributing to “an exceptionally rapid and exciting period of cultural change.” The curriculum runs chapter by chapter through George Kennan, George Orwell, Jean-Paul Sartre, Hannah Arendt, Jackson Pollock, Lionel Trilling, Allen Ginsberg, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Robert Rauschenberg and John Cage, Elvis and the Beatles, Isaiah Berlin, James Baldwin, Jack Kerouac, Andy Warhol, Susan Sontag, and Pauline Kael. Each biography opens a door to a school or trend of work. At first, the persona is squeezed for color and human interest. Here, pared down slightly, is the period’s best-known philosopher:

Sartre was five feet two inches tall … He was conscious of his ugliness—he often talked about it—but it was the kind of aggressive male ugliness that can be charismatic, and he wisely refrained from disguising it … He was also smart, generous, mildmannered, extremely funny, and a great talker … Sartre liked other people to like him—which, in social situations, can be almost as good as liking other people. He was a gifted mimic, he looked surprisingly good in drag, and he did a great Donald Duck impression. He enjoyed drinking and talking all night, and so did [Simone de] Beauvoir.

The disorienting trick of this approach is that these central figures are then popped inside out, and they, too, become intermediaries for, or transfer points to, many other personages, artists, thinkers, salespeople, propagandists. Menand’s is not a “great man” view of history, because no one seems particularly great. One gets a feeling for Sartre as a person, a limited knowledge of how Sartre made Being and Nothingness, and a vivid sense of how the book made Sartre a celebrity. Then one learns how a troupe of others came along and rode his success like a sled.

Menand zooms in and out between individual egomaniacs and the milieus that facilitated their ascent and profited from their publicity. The results—group biographies, in miniature, of the existentialists, the Beats, the action painters, the Black Mountain School, the British Invasion, the pop artists, and many coteries more—are enchanting singly but demoralizing as they pile up. All of these enterprises look like hives of social insects, not selfless quests for truth or beauty. Menand is a world-class entomologist: He can name every indistinguishable drone, knows who had an oversize mandible, who lost a leg, who carried the best crumbs. The caution is that you must not seek lasting value in their collective works. From this vantage, the monuments really are just anthills.

Menand is truly one of the great explainers. He quotes approvingly a lesson taken by Lionel Trilling from his editor Elliot Cohen: “No idea was so difficult and complex but that it could be expressed in a way that would make it understood by anyone to whom it might conceivably be of interest.” Menand puts his own practice to the test. He is accurate, he is insightful, and he is not a dumber-downer. It is notoriously hard to summarize Martin Heidegger’s Being and Time, structural linguistics, serial composition in music, or the formation of Great Power rivalries in the period of decolonization. Menand’s account of each is an abbreviated tour de force. His explanations work at all levels: interpretation for scholars, review for general readers, introductions for neophytes. Where another writer would take 20 pages to tell us why someone or something mattered historically, Menand does it in two.

The Free World is a treasury of details. Some complicate myths without displacing them. Jack Kerouac did not actually improvise On the Road in three weeks on a scroll of teletype paper, high on speed. He did type On the Road in three weeks on a scroll, as a revision of many previous drafts, while drinking coffee. Jackson Pollock was not an uninhibited wild man, did not cut the ends off the landmark painting Mural to fit it on Peggy Guggenheim’s wall, and probably did not piss in her fireplace at the party where it premiered. He was an alcoholic, however, and exhibited sudden inebriated shifts in mood. He was mortified and depressed by the mythmaking photographs and film that Hans Namuth shot of him throwing paint at the canvas, leading to a significant breakdown.

Menand endows some minor incidents with greater dignity. Criticized for his feckless interventions into politics, James Baldwin may actually have helped galvanize the Kennedy administration’s support for civil rights, when he and an entourage of entertainment friends browbeat Robert F. Kennedy at a much-derided celebrity summit. Other discoveries are bummers. De Gaulle deliberately reentered Paris at the liberation with only white soldiers from his Free French Forces, though the majority of his troops had been recruited from French colonies in Africa. Behind Robert Rauschenberg’s win at the Venice Biennale in 1964, a landmark for postwar American art, may have been a successful plot by his gallerist and publicist to influence the jurors.

Most of the memorable details are just funny. The titanic French intellectual Claude Lévi-Strauss taught as “Claude L. Strauss” in America to avoid confusion with the blue-jeans manufacturer. American tourists may have begun to complain about French rudeness only when France ceased to be their bargain-basement destination, after the hugely favorable postwar exchange rate of dollars to francs was moderated in a 1958 currency stabilization.

The underlying theory of the book rests on a picture of what makes for “cultural winners,” works and ideas that Menand defines as

goods or styles that maintain market share through “generational” taste shifts—that is, through all the “the king is dead; long live the king” moments that mark the phases of cultural history for people living through it.

This definition might seem to make a “cultural winner” synonymous with a “classic,” a work whose influence persists and evolves because of inherent artistic value. Menand’s recountings are less concerned with the changing meanings of individual works than with their successive adoptions and co-optations, in defiance of depth and meaning. It is a process of “winning” often based on cults of personality, indifference to complex origins, and the fortune or misfortune of timing. One sentiment repeated with variations throughout the book is “The timing was good” (for the appearance of Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism in 1951, when Stalin seemed to have taken the place of Hitler). “The timing was lucky” (for cheaper pop art to appeal, in 1962, to impecunious collectors during an economic downturn). “Everything was set for a new culture hero to walk [onstage]. As if on cue, one did.” (This was Sartre in 1945, when the Nazi occupation ended and he delivered a philosophy of freedom that “turned France’s wartime experience into a metaphor.”)

The thrust of many of Menand’s retellings is that “in the business of cultural exchange, misprision is often the key to transmission.” Fame comes through misreadings, fantasies, unintended resonances, charisma, and publicity. Often Menand’s point seems to be that the culture’s reigning talkers and salespeople and debaters need to conjure figures to venerate and attack (in ceaseless alternation) for short-range purposes of attention and competition. Any given work—1984, say, or Bonnie and Clyde—isn’t much of anything until it becomes a counter in other people’s games. How much pure hucksterism is involved on the part of the cultural arbiters, as opposed to astute positioning of worthy work so that it will thrive in the market, can be hard to tell. What Menand himself makes of George Orwell’s remarkable novel or Arthur Penn’s film is difficult to discern, so scrupulous is he in his hygiene of settling artistic value solely in the context of the times.

In particular, the inability to tell the difference between a joke and a real expressive creation keeps cropping up in Menand’s vision of cultural progress by means of misreadings. Elvis Presley felt little commitment to “That’s All Right, Mama,” but undertook it while “kidding around,” he said. He juiced the performance by “acting the fool,” according to a fellow musician. Sam Phillips of Sun Records pulled it out from an early recording session, pushed radio airplay, and made it a rock-and-roll breakthrough. (The song’s African American originator, Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup, never got a royalty from Elvis’s sales. Crudup himself had likely lifted much of the song uncredited from Big Joe Turner.) Menand says much the same was true of Presley’s epochal “bump-and-grind” version of “Hound Dog,” delivered first on The Milton Berle Show in 1956, then repeated on The Ed Sullivan Show. Though Elvis was certainly a gyrating, passionate singer, this famous routine—rerun a thousand times, as the cultural desublimation of the white male American pelvis—started as self-conscious burlesque, “tongue-in-cheek, a joke.”

The central question of this period in culture might be whether U.S. artists lived up to expectations. In 1945, Europe was in ruins. America was rich and productive and dictated the terms of the postwar economic and political order. Certainly the U.S. had the power to pretend to cultural glory, too. But was it a pretense, or did Americans really continue and exceed the prewar triumphs of European modernism? Most histories of the arts after 1945 assume that the greatest American successes deserved their fame.

Menand does too, I think—though it is hard to be sure. The paradoxical feature of the book is that its stylish, comprehensive retellings of some of the most famous stories of the most famous individuals, weaving connections between them, made me doubtful and weary of them, and much more interested in minor figures whom we barely glimpse. (Funny that in this book Josef Albers, Ralph Ellison, and Aimé Césaire become such “minor figures”—because the more peripatetic fame seekers like Rauschenberg and Baldwin are pushing their way in front of the camera instead.) As for the construction of art history in “schools” or “groups,” the effect of The Free World’s explain-don’t-judge perspective on canon formation is to leave many of the major art movements looking negligible or meretricious, floated on excesses of cash, power, and mass media.

Menand is notably excellent on how commercial, regulatory, and technological changes determined which kinds of artwork made it to the public. His analysis helps demystify trends in commercial forms like film and pop music, especially when they otherwise seemed to run against the grain of pure profit. “Foreign film” in America in the ’50s and ’60s—when independent art cinemas emerged, showing imports such as work by Ingmar Bergman and the French New Wave—proves to have been energized by a successful federal-government antitrust action against the monopolistic Hollywood studios. So, too, with the anarchic spirit of the new popular music. “Where did rock ’n’ roll come from?” Menand wonders. He answers that it was “the by-product of a number of unrelated developments in the American music business” that redirected sales to teenagers, and also the result of new radio-station competition, the partial racial desegregation of the music charts, and the arrival of 200-disc jukeboxes.

The idea of a “culture industry”—originally an oxymoron coined in 1947 to sum up the danger facing art (for how could personal culture be churned out on an industrial model?)—is used unironically by Menand to name the vastly scaled-up production and consumption of all artistic experience. “The culture industries, as they expanded, absorbed and commercialized independent and offbeat culture-makers, and the university, as it expanded, swallowed up the worlds of creative writing and dissident political opinion.” With his eye on this process, we miss out on artists and thinkers who dug deep and stayed home, who produced as hermits or eccentrics or introverted students of their art. And I wondered about rival art forms and streams, such as jazz from 1945 to 1970. Bop, post-bop, and free jazz evolved an American art music that was the real successor to Debussy, Schoenberg, and Bartók (never mind John Cage). It gained in artistic complexity and superiority even as it decreased in market share.

Menand’s famous artist-protagonists seem haunted by a dialectic of shame and shamelessness, perhaps as a side effect of the rising tide of money and publicity swamping their actual accomplishments. His most searching and illuminating portraits are of figures at the extremes. People who found themselves cringing at celebrity—Pollock, Trilling, and Kerouac—come in for compassionate treatment as they struggle unhappily with their success, annihilating themselves in alcohol or psychotherapy. But the extroverts, who were willing to go on any TV show, travel anywhere, meet anyone, and who liked to provoke as much as they liked to create, gain even more from Menand’s studiously neutral dissection of a process in which the connections between people, rather than quality of work, are what make for centrality.

He’s particularly sympathetic to the most wised-up among them. The pages on Andy Warhol are unexpectedly sensitive and moving, precisely because of the total depthlessness of Warhol’s stance and his dedication to relentless productivity, his touching desire to participate in the art world. Menand is fondly impressed, too, by the shared self-promotion of Rauschenberg, who pulled disparate objects like stuffed goats and trash and corks into his visual-art “combines,” and his collaborator Cage, the composer best remembered for his noteless, silent piece, 4’33”. They alternately charmed tastemakers and trolled them—and they knew to play the long game. “Rauschenberg would later recall with amusement the days when he was regarded as a jester,” Menand writes. “Cage wanted recognition … Like Rauschenberg, he didn’t care very much if other people considered him a clown.” Menand does not seem to think they were clowns in the end, but he does surprisingly little to reassure the reader.

Menand’s book bequeaths the sense that the last laugh may truly have been on the self-seriousness of a whole historical period, one that treated its most publicized and successful arts figures far too generously, giving them too much credit for depth and vision, while missing the cynical forces by which they’d been buoyed up and marketed. It is an unillusioned book appropriate to our disillusioned times. I can imagine The Free World leaving my hypothetical college senior, denizen of the bleak attention economy of the 21st century, feeling liberated to discover that culture was no better—no more committed to a quest for what is true, noble, lasting, and beautiful—in the world of the Baby Boomers and beaming grandparents. I, too, finished The Free World relieved to know that this book will henceforth be on my shelf to consult when I forget why innumerable great names were once remembered, and to preserve me from the call of future books titled Why X [or Y] Still Matters, by confirming that X and Y probably don’t. The book is so masterful, and exhibits such brilliant writing and exhaustive research, that I wonder whether Menand could truly have intended where his history of the postwar era landed me. I learned so much, and ended up caring so much less.

This article appears in the June 2021 print edition with the headline “The Opportunists.”