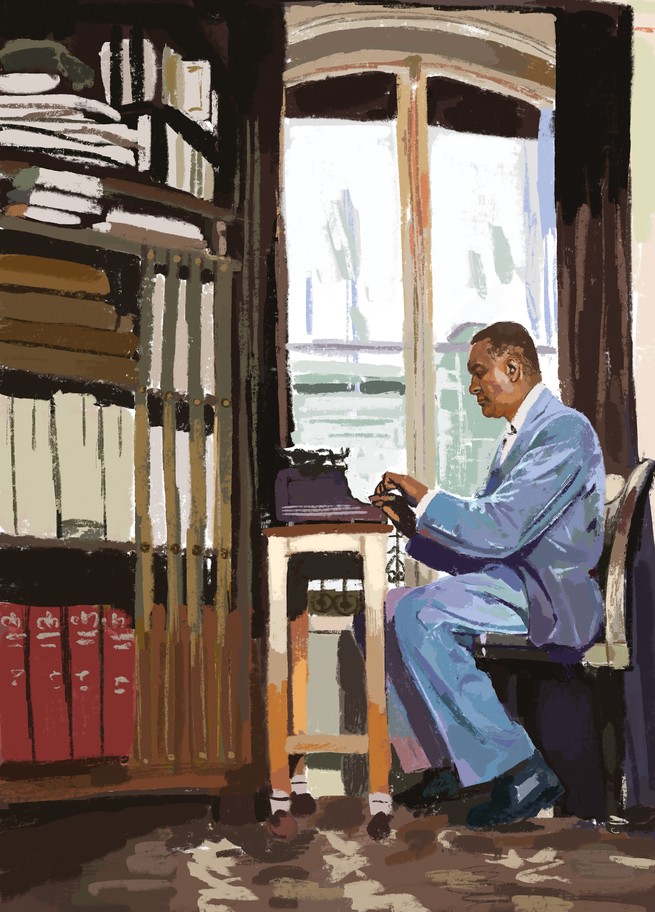

The Bleak Prescience of Richard Wright

A previously unpublished novel invites a reassessment of a writer criticized for his doctrinaire pessimism about race in America.

This article was published online on May 7, 2021.

Richard Wright, the father figure of African American literature, both nurtured and was rejected by his two most conspicuous heirs, Ralph Ellison and James Baldwin. Wright, who took Ellison under his wing in New York in the late 1930s, told his acolyte to stop copying him, that he was mimicking, not cultivating his own style. Ellison responded that he was trying to learn to write well by imitating his mentor. That was when they were close. Baldwin, too, started out as a pupil and an admirer who saw Wright poised to be the greatest Black writer in the United States.

Though it happened slowly, by 1941, Ellison betrayed signs of feeling that Wright, affiliated off and on with the Communist Party, wrote fiction that was too ideological and not sensitive enough to nuance: Wright wanted to testify to the monstrosities of white supremacy, rather than the power of Black resilience. Ellison grew committed to the poetry of American democracy, despite how badly it was sullied; he swore by the virtues of individualism. Calling Wright “Poor Richard,” Baldwin joined Ellison in lamenting their mentor’s failure to see the beauty of Black people. The two of them never ceased to love Wright’s prose, but they came to reject his perspective.

I admit I’ve been inclined to share their verdict, based on Wright’s first novel, Native Son, published in 1940, which I read again and again in classes before and during college. I’ve parroted the notes I took in lectures, and I’ve taught a version of those lectures myself: Bigger Thomas was a protagonist stripped of any redeeming qualities, so distorted by the conditions of racism that he became an avatar more than a character, and an unsettling representation of Blackness.

My assessment of Wright has begun to shift over the past couple of years. I’ve read 12 Million Black Voices (1941)—his reflections on the Great Migration, accompanied by Farm Security Administration photographs taken during the Depression—and been struck by his broad sympathy. And I’ve reread Black Boy (1945), a memoir I hadn’t touched since my final year of high school in the Northeast, in a writing seminar led by a teacher born, like me, in Birmingham, Alabama. Wright reached for the very core of the human condition in his portrait of growing up destitute in the Deep South during the early 20th century, and then making his way north: abundance everywhere and terrible hunger, tragedy mixed with the quotidian in the most disorienting ways. The experience he evoked might not have been every Black life, but it was indeed a part of Black life. In Mississippi, the land could swallow you whole. In Chicago, a rat might bite you, because after all, you were made to live in slums no different from rattraps. Wright was showing us something true, if not absolute—how, with the plantation breathing at your back and deferred dreams before you, tragedy happened.

Now that I’ve read The Man Who Lived Underground—a previously unpublished novel held in the Wright archives, also written in the early 1940s—I’m even more convinced that Wright deserves to be looked at with fresh eyes. At first, I texted a friend, “This novel is clearly a direct model for Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man.” My friend wrote back, “That’s why he told Ellison to stop copying him!” Wright’s protagonist is a Black man who is falsely accused of a double homicide and brutalized by the police before escaping into a sewer. Ellison’s protagonist is also a Black man who eventually retreats into a sewer, on an identity quest that has been thwarted aboveground. Yet I quickly discovered that Wright was mapping an unexpected journey.

Though Native Son had been a best seller, Harper rejected The Man Who Lived Underground, its immediate successor. Readers’ comments in the archives suggest that the editors might have been deterred by the “unbearable” police violence and an imbalance between allegory and graphic detail. The book opens with a harrowing encounter between decent, respectable Fred Daniels, the protagonist, and three police officers. Fred is subjected to torture so extreme that he’s left barely conscious. He loses track of everything in the horror of the moment. His identity disappears, time is drained of meaning, he forgets his pregnant wife and grows unsure about his innocence. The unheimlich, Freud’s idea of the unfamiliar familiar, is a constant presence for Wright: Nothing makes sense, and yet he and we know that this is the way the world is. And then, almost as if in a dream, Fred realizes that the officer guarding him has briefly walked away, and “a vague gathering of all the forces of his body urged him to escape.” Like a disoriented, curious child, he gravitates toward a “gaping manhole.”

The sewer provides a nightmarishly sensual experience. What sounds like a holler might be a skidding car. The slosh of water turns to sludge; a baby passes by him, dead and flushed away. Ellison’s invisible man escapes into an Emersonian isolationism—a reckoning with himself underground. Wright scripts a surreal reencounter with the world as seen through discovered cracks and doors that reveal hidden interiors: In his subterranean wandering, Fred comes upon the basement of a Black church, drawn to it by singing that he finds at once “sonorous and magnificent in its expression of melancholy renunciation” and infuriating in its guilty “whimpering.” He happens on the safe room of a real-estate office, and ends up complicit in a theft that results in another man’s punishment. He finds himself in a coal bin, saved from being scooped up by a worker only because the exhausted old man works in the dark, never turning on the lights.

Viewed from below, the social world, the economy—all manner of ordered things—are clearly absurd. Reason eludes Fred, and empathy flows in at the vision of humanity as “children, sleeping in their living.” After all, what really matters? This isn’t the doctrinal Wright, warning us of the disasters that capitalism creates. This is an unmooring Wright, pushing us past the edge of social analysis and into madness. Perhaps this turn, from leftist literary naturalism to a morbid unraveling of the self, is what most disturbed the Harper editors.

It’s impossible to read Wright’s novel without thinking of this 21st-century moment, when we urgently assert, “Black lives matter.” We live with cycles of repeated violence; the terror of Black innocents being killed is all around us and in our consciousness. Starting in the 1940s, Ellison and Baldwin criticized Wright for his insistence on dramatizing this ineluctable subjugation; they saw Wright himself as submitting, in the process, to Black oppression in America. They believed, each in his own fashion, that Black literature ought to capture hope, possibility, beauty, and endurance. Transcendence and, more important, transformation were possible until they weren’t. Now the tragic absurdity of Fred’s life seems all too familiar. We see it on our screens regularly: the snuff films of white supremacy. Perhaps we have too readily judged Wright’s bearing of witness to be reductively stark and fatalistic. What he observed is still happening, despite all those generations of unyielding hope.

Critics will no doubt liken The Man Who Lived Underground to Kafka, Dostoyevsky, and Sartre. And the analogies are there in Fred’s drive to “assert himself,” to act in the face of “death-like” existence. But the novel is also a Protestant work, as much about God as it is about Black people, as Wright himself explains in an accompanying essay about the novel’s origins titled “Memories of My Grandmother.” In a world beyond understanding and reason, his Seventh-day Adventist grandmother had a religion that imposed meaning on the incomprehensibility of existence. She believed, in accordance with Church doctrine, that right and wrong were starkly distinguished. Strangeness was not to be explored, but simply judged. Guilt preceded assessment: Humans were guilty, and only holiness could save them. In its own way, this fierce Black Protestantism gave psychic refuge to believers but also recommended surrender to the cruelty of the world. In Fred’s odyssey, which leads him back aboveground to confess to the crime he didn’t commit, Wright has him careen from rage at the pervasive burden of guilt to an embrace of it.

As I read, I was reminded of Lorraine Hansberry’s thoughts about Wright’s contested literary status. Like her fellow writers, she valued debate over how best to use literature as a tool of social criticism, but she felt that Baldwin’s attack on Wright was too harsh—as if Wright had to plummet in order for his own star to rise. She disliked the pleasure that white critics took in this literary patricide. In her view, very few American writers could match Wright’s skill and style.

Wright deserves sensitive reconsideration, especially now that so many of us have been proved naive in our belief that an honest rendering of Black people might lead to recognition of our existence in the universality of humanity. When Wright became an expatriate, in the late ’40s, he did not turn his back on America. He found a vantage point that allowed him to understand better what actually went on in a country where Black people “are accused and branded and treated as though they are guilty of something,” as he wrote in his essay. Baldwin, who also moved to France, eventually came to a similar conclusion that with distance from the U.S. came newly clear-eyed intimacy.

I write, again and again, that things have changed for Black Americans, as unjust as the world remains. I say that Black people have displayed remarkable endurance and transformed so much. And yet, I wonder. When the novelist and poet Margaret Walker looked at Richard Wright, a man she loved completely, she worried that he capitulated too easily to the violence. But he, a child of the Black Belt, was up close to it in a way that Walker, a Birmingham-born preacher’s daughter, simply wasn’t. Nor am I. I have visited a squatter’s residence, a crack house, a federal prison, but I haven’t lived in any of them. I have been falsely accused and unfairly judged, but never beaten senseless in the process.

Wright tells an old story that still lives. His Fred carries the name of our most famous Black fugitive, the abolitionist writer Frederick Douglass, and he travels underground in ways more reminiscent of the Underground Railroad than of Dostoyevsky. He finds himself encountering the world, unfiltered by established terms of order, and acquires a tenderness for all people. In the end, his Black existence presents a particular window and a universal predicament—and a reminder: Surrounded by ghastly forces every day, we destroy life with our many idolatries and illusions.

This article appears in the June 2021 print edition with the headline “What Richard Wright Knew.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.