The Torture Memos, 10 Years Later

Our journey toward Abu Ghraib began in earnest with a single document -- written and signed without the knowledge of the American people

On February 7, 2002 -- ten years ago to the day, tomorrow -- President George W. Bush signed a brief memorandum titled "Humane Treatment of Taliban and al Qaeda Detainees." The caption was a cruel irony, an Orwellian bit of business, because what the memo authorized and directed was the formal abandonment of America's commitment to key provisions of the Geneva Convention. This was the day, a milestone on the road to Abu Ghraib: that marked our descent into torture -- the day, many would still say, that we lost part of our soul.

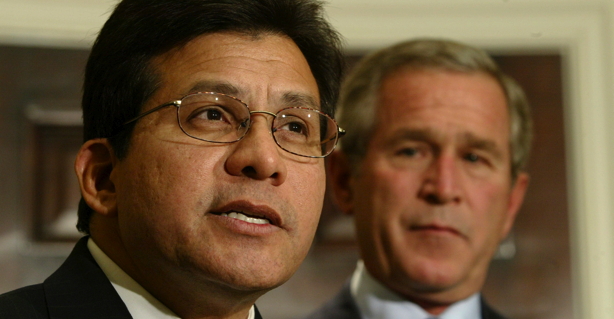

Drafted by men like John Yoo, and pushed along by White House counsel Alberto Gonzales, the February 7 memo was sent to all of the key players of the Bush Administration involved in the early days of the War on Terror. All the architects and functionaries who would play a role in one of the darker moments in American legal history were in on it. Vice President Dick Cheney. Attorney General John Aschroft. Secretary of State Donald Rumsfeld. CIA Director George Tenet. David Addington. They all got the note. And then they acted upon it.

When we talk today of the "torture memos," most of us think about the later memoranda, like the infamous "Bybee Memo" of August 1, 2002, which authorized the use of torture against terror law detainees. But those later pronouncements of policy, in one way or another, were all based upon the perversion of law and logic contained in the February 7 memo. Once America crossed the line 10 years ago, the memoranda that followed, to a large extent, were merely evidence of the grinding gears of bureaucracy trying to justify itself.

There will likely be other opportunities in 2012 to look back at some of those other memos. Perhaps Jay S. Bybee himself, inexplicably rewarded for his role in the scandal by getting a federal judgeship, will say something. Let's leave that for the dog days of August. Today is a day instead to look at one of the first of these odious documents. It is a day to note how simple and easy it was, it still is, for political leadership to make monumental decisions on our behalf without really telling us -- or by simply telling us something that isn't true.

This is not a nostalgic indictment of the Bush Administration's approach to the detainees. Ten years later, the topic is still timely. Right now, another administration is justifying another extraordinary departure from American legal policy-- the assassination of U.S. citizens abroad, with drone strikes, in a secret manner, without affording those citizens any due process. Trust us, the Bush folks said, when it comes to treatment of detainees. Trust us, the Obama White House says, now when it comes to which citizens we are entitled to kill without trial.

Before the Memo

On September 18, 2001, just one week after the terror attacks upon America, President Bush signed the Authorization for use of Military Force. He did this a mere four days after Congress had passed the extraordinary measure by overwhelming margins (98-0 in the Senate, 420-1 in the House of Representatives). The Congressional authorization was essentially a blank check to the executive branch to go after the people who had taken down the Twin Towers. The U.S. now was authorized "to use all necessary and appropriate force" against them.

This language -- with its obvious and ominous international design -- immediately raised the eyebrows of the folks at the International Committee of the Red Cross. They smelled a rat. And so they shared their concerns with the State Department and then they went to the United Nations. On October 11, 2001, exactly one month after the attacks, a U.N. High Commissioner issued this brief letter reminding his host country of the "non-derogable nature" of its obligation to the Geneva Convention against Torture. The UN wrote:

The Committee against Torture is confident that whatever responses to the threat of international terrorism are adopted by State parties, such responses will be in conformity with the obligations undertaken by them in ratifying the Convention against Torture.

In conformity with the obligations undertaken. By early January 2002, lawyers for the White House and the Defense Department had ginned up an argument they reckoned they could sell with a reasonably straight face, both to their superiors in the Bush Administration and then, if need be, to the international community or a future court of law. We only have to be in conformity with the obligations undertaken by the Geneva Convention, they argued, if we have obligations under the Convention, and we only have those obligations if and when we say so.

It is at this point that Alberto Gonzales played another of his dubious roles in U.S. history. As White House counsel, he first pitched the argument to his old Texas pal, the president, who promptly bought it. No surprise. Even back then, the two had a long history of enabling one another's legal malfeasance. However, Gonzales got push-back from Secretary of State Colin Powell, the decorated war hero, who argued that U.S. soldiers would pay the ultimate price for their government's decision to blow off the Geneva Convention on Prisoners of War.

This prompted Gonzales to write a memo, on January 25, 2002, that is still chilling to read. In it, he argued that the War on Terror required new interpretations of old rules. He wrote: "This new paradigm renders obsolete Geneva's strict limitations on questioning of enemy prisoners and renders quaint some of its provisions requiring that captured enemy be afforded such things as commissary privileges." By making the War on Terror sound like an episode of Hogan's Heroes, in other words, Gonzales convinced President Bush to see things his way.

What the February 7 Memo Said

In retrospect, It's hard to know what is more offensive about the memo -- the policy it adopted or the language it employed in doing so. From its title on down, the two-page document sought to reassure future readers (and judges and jurors) that the administration had found a lawful balance between the mandates of the Geneva Convention on prisoners of war and the mandate government officials wished to deploy in prosecuting the War on Terror. Whatever else it was, the memo was dishonest by its own terms, a mess of inherent contradiction.

Echoing the Gonzales memo two weeks earlier, the February 7 memo began by arguing briefly that the United States was not bound by its obligations under the Geneva Convention because the international treaty applied only to "High Contracting Parties" and not stateless entities like Al Qaeda; because it contemplated "the existence of 'regular' armed forces" unlike the quasi-criminal/quasi-terrorist plotters of 9/11; and because "the new paradigm" of the War on Terror required "new thinking" about America's commitment to international norms.

So President Bush signed a document which stated:

"... none of the provisions of Geneva apply to our conflict with al Qaeda in Afghanistan or elsewhere through the world because, among other reasons, al Qaeda is not a High Contracting Party to Geneva."

... common Article 3 of Geneva does not apply to either al Qaeda or Taliban detainees because, among other reasons, the relevant conflicts are international in scope and common Article 3 applies only to 'armed conflict not of an international character."

... I determine that the Taliban detainees are unlawful combatants and, therefore, do not qualify as prisoners of war under Article 4 of Geneva. I note that, because Geneva does not apply to our conflict with al Qaeda, al Qaeda detainees also do not qualify as prisoners of war.

... I hereby reaffirm the order... requiring that the detainees be treated humanely and, to the extent appropriate and consistent with military necessity, in a manner consistent with the principles of Geneva.

After turning the CIA and others agencies loose upon terror suspects, after unmooring the United States from its generations-long commitment to the Geneva Convention, after offering the legal and political authority for what would come to be called, euphemistically, "enhanced interrogation," President Bush signed a memo that offered this:

Of course, our values as a nation, values that we share with many nations in the world, call for us to treat detainees humanely, including those who are not legally entitled to such treatment. Our nation has been and will continue to be a strong supporter of Geneva and its principles. As a matter of policy, the United States Armed Forces shall continue to treat detainees humanely and, to the extent appropriate and consistent with military necessity, in a manner consistent with the principles of Geneva (my emphasis).

Poof. Just like that, with no judicial review, meaningful Congressional oversight, or public scrutiny, and based significantly upon the recommendations of a man, Alberto Gonzales, who is among the most hapless in the history of American governance, the United States became an outlier to the Geneva Convention, an international scofflaw. Within days of this memo, reports Larry Siems in his epic book, The Torture Report, American officials were training military interrogators on how to "exploit" terror law detainees by torturing them.

The Aftermath

We will never know how Americans would have reacted had they been told, in real time, what monumental policy change President Bush was making on their behalf on February 7, 2002. As near as I can tell, the document was declassified only in June 2004, after much of the memo's impact had become known to the world. In hindsight, it's comforting to fantasize that the American people, or at least enough federal lawmakers and judges among them, would have stood up and said no to this perversion of law -- and of the rule of law.

.

Coming less than five months after the terror attacks, however, it's more likely that the "new thinking" contained in the February 7 memo would have been wildly cheered by an America that is, even 10 years later, churned up with anger over 9/11. We shouldn't fool ourselves on this grim anniversary, or throughout this coming year of dubious anniversaries of the War on Terror, into thinking that a new era is here. In many ways, from the Guantanamo detainees on upward, we are still too blind to see, or honestly acknowledge, the damage we've done.

The February 7, 2002, memo begat the mistreatment of Iraqi prisoners at Baghdad's Abu Ghraib -- a disaster for America's image in the world (and particularly the Muslim world). The memo begat the torture of terror suspects whose subsequent testimony, far from being more reliable, instead bogged down potential prosecutions of dozens of the detainees, in either civilian or military court. The detainee facility at Gitmo is still open today, you could argue, as a direct and proximate cause of the memo 10 years ago.

The directive brought about a few lawsuits against its drafters -- a possibility, we now know, that was definitely on their minds back then. The torture memos were odious instruments of policy, sure, but they were also CYA memos, perhaps the most significant CYA memos in American history. And ten years later, we still don't fully know what we don't know, to use a phrase from back in the day, because many vital documents are still classified. Let's all come back here in 10 years, or in 20, or 30, and see how the view has changed.

The Anniversary

None of this breaks new ground. Many scholars, much smarter than I am, have chronicled the torture memos and their impact upon American law, politics, diplomacy, and morality. Nor do I suggest that that February 7, 2002, is a date every person interested in this topic ought to regard as the granddaddy of the torture memos. The August 2002 memos, which expressly justified the "enhanced interrogation" methods, are also a pivotal point. But this isn't a race or a contest. And there are plenty of disconcerting anniversaries to go around this year.

As a nation, we should commemorate this anniversary not only because we should always strive to hold ourselves responsible for our mistakes. We should also mark the day because it may help us muster the courage today to ask the right questions of the Obama White House about its extraordinary drone program. The executive branch says, without a full public explanation, that it may lawfully and unilaterally judge an American citizen abroad guilty of terrorism and then shower that citizen with a missile from the sky without indictment or trial.

Surely this expression of presidential power, exercised already in the case of Anwar al-Awlaki, warrants a closer look by the other branches of government. Last year, for example, a federal trial judge ruled that he while he was intrigued by claims from al-Awlaki's father that the American government had unjustifiably murdered his son, federal law precluded him from doing anything about it. A year earlier, the same judge had ruled that the same father had no right to challenge the allegations against his son. Congress couldn't care less.

Yet we cannot even see the legal memo(s) upon which the drone program is based, much less evaluate the documents for their loyalty to the Constitution and to the rule of law. The ACLU sued the feds last week for such access under the Freedom of Information Act. Good luck with that. My questions today are more specific. Why hasn't Congress pushed the administration to justify itself? Why haven't the courts yet embraced litigation that would shed light? The answer, 10 years later, is depressing: we are still too blind, too blind to see.